- Who We Are

- What We Do

- Our Issues

- Our Projects

- Sprawl Retrofit

- Highways to Boulevards

- CNU/ITE Manual

- Health Districts

- The Project for Code Reform

- Lean Urbanism

- LEED for Neighborhood Development

- Missing Middle Housing

- Small-Scale Developers & Builders

- Emergency Response

- HUD HOPE VI

- Rainwater in Context

- Street Networks

- HUD Finance Reform

- Affordable Neighborhoods

- Autonomous Vehicles

- Legacy Projects

- Build Great Places

- Education & Trainings

- Charter Awards

- Annual Congress

- Athena Medals

- Resources

- Get Involved

- Donate

- Membership

- Public Square

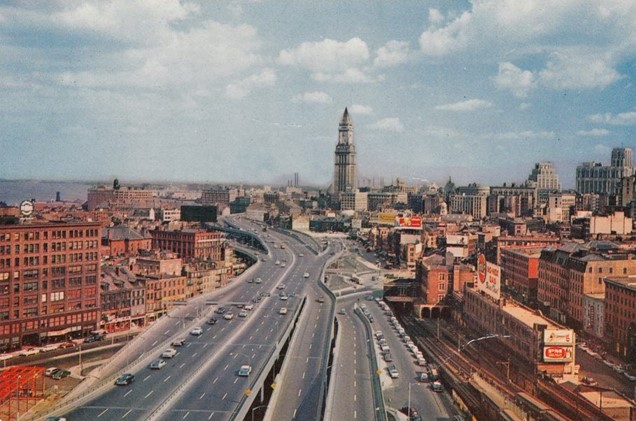

When Boston opened the Central Artery highway in 1959, it effectively serviced an estimated 75,000 vehicles daily. The construction of the highway displaced 20,000 residents during construction and cut off Boston’s North End and Waterfront neighborhoods from its downtown. By the 1990s, the Artery became congested for more than 10 hours a day as nearly 200,000 vehicles tried to move to and from central Boston. The highway’s accident rate rose to four times the national average. Boston’s tunnels under the harbor connecting downtown Boston to East Boston were experiencing similar congestion.

The Big Dig

Undertaken in the mid-1990s, Boston’s plan to remediate the congested Central Artery—nicknamed locally the Distressway—was named the Central Artery/Tunnel Project (CA/T), and was constructed under the supervision of the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority. This ambitious project included replacing the six-lane highway with an eight-to-ten lane underground expressway beneath the existing road, ultimately leading to a 14-lane, two-bridge crossing above the Charles River. Upon completion of the underground expressway, the former, elevated expressway was demolished and replaced with open space and urban infill development.

Furthermore, I-90 (the Massachusetts Turnpike) was extended from its former terminus south of downtown Boston through a tunnel beneath South Boston and Boston Harbor to Logan Airport, the first connection completed in December 1995.

Before

After

Results

The Big Dig was undoubtedly a costly highway expansion that perpetuates Boston’s car-dependency. The $24 billion project temporarily eased downtown congestion, mainly by shifting bottlenecks to points north and south. Parallel investments in public transit that the state promised in conjunction with the highway’s expansion (a Red-Blue line connector from Government Center to Massachusetts General Hospital, the extension of the Green Line through Somerville, the extension of the Blue Line to Lynn, and the restoration of Green Line service through Jamaica Plain) never materialized.

Still, burying the highway has brought some benefits to Boston. In the path of the old elevated Central Artery now stands the Rose Kennedy Greenway, a 17-acre linear park that links downtown and adjacent neighborhoods that were formerly separated by the highway. The Big Dig has also served as a catalyst for real estate development and helped restore Boston’s waterfront as an amenity. Original projections estimate that the Big Dig has attracted $7 billion in private investment, including 7,700 housing units, 10 million square feet of commercial space, 2,600 hotel rooms, and 43,000 new jobs in the city.