Alexander’s Oregon patterns: Campus design, part 2

This is the second in a series of ten essays that present innovative techniques for designing and repairing a corporate or university campus. These tools combine New Urbanist principles with Alexandrian design methods. Even though Christopher Alexander is widely known for his “Pattern Language”, an earlier book developing design patterns specific to a university campus is almost forgotten. The method is revolutionary when compared to the dreary industrial model implemented almost universally nowadays (and is the reason for this neglect). Reference will be made to eight city types as described in my book-length paper “Eight city types and their interactions”. These are labeled: Nourishing-physical, Fractal, Network, Spontaneous self-built, Virtual, Developer, Anti-network, and Inhuman. Every city, and each region of a city, is some mixture of these eight city types.

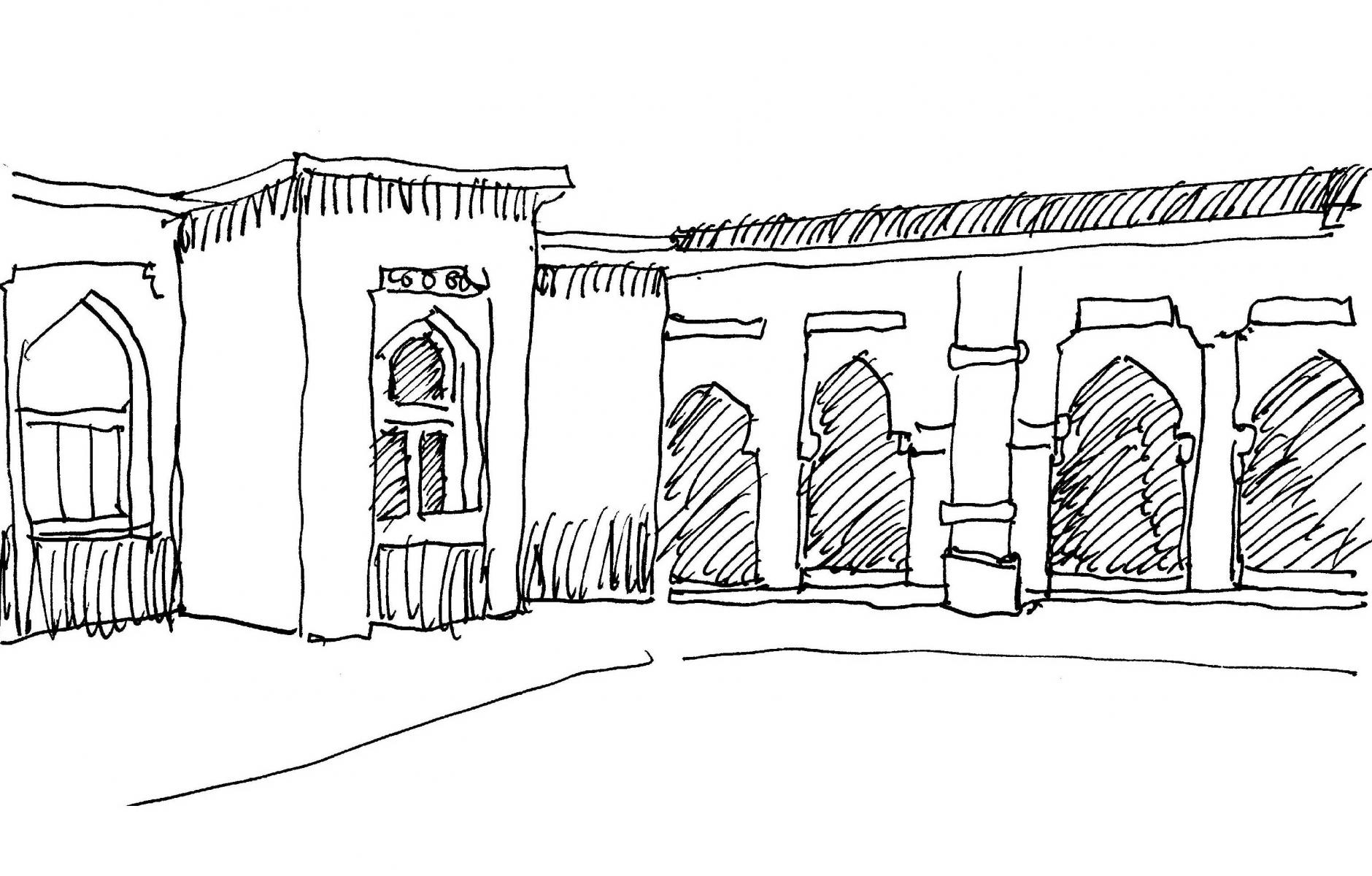

Alexander's Oregon patterns

Christopher Alexander derived design rules for the University of Oregon campus in 1975, and those rules are universal.

We can apply the Nourishing-physical + Fractal + Network city (Salingaros, 2017) to design a campus that will contain all the positive qualities of our best-loved historical institutions. A college or university campus represents an urban microcosm, with its limited yet often extensive area and restricted mixture of uses. One needs different buildings for classrooms, research laboratories, libraries, student housing, cafeterias and student activities, sports, maintenance, administration, etc. The pedestrian realm is paramount, since students have to walk from building to building. Essential vehicular connections ideally go around or under the main network of pedestrian paths.

Christopher Alexander created a long-term planning strategy for the University of Oregon based on design patterns. Some of those patterns appear in his classic book A Pattern Language (Alexander et al., 1977), whereas others are to be found only in the lesser-known The Oregon Experiment (Alexander et al., 1975). I recall some of those findings here, and explain how they apply to the eight-fold classification of city types. The pattern descriptions given below are my own summaries.

Oregon Pattern 2: Open university. “Do not isolate the university by surrounding it with a boundary; instead, interweave at least one side of the campus into an adjoining city, if that is possible.”

Oregon Pattern 3: Student housing distribution. “Locate some student housing within the center of the campus, with different percentages in regions as one moves away from the center. The first 500 m radius containing ¼ of the resident students; ¼ in a ring between 500 m and 800 m radius; and the rest outside 800 m.”

Oregon Pattern 4: University shape and diameter. “If possible, situate classrooms within a central core of ½ km radius, and non-class activities such as administration, sports centers, and research offices outside.”

Oregon Pattern 5: Local transport area. “Give priority to pedestrian flow in the central core of the campus, within a radius of ½ – 1 km. Vehicular traffic here must be made to go on slow and circuitous roads.”

Oregon Pattern 12: Fabric of departments. “While each academic department ought to have a home base, it should be able to spread over into other buildings and interlock with other departments.”

Implementing the Network city (Salingaros, 2017) prevents cultural and social fragmentation, while the Fractal city (Salingaros, 2017) helps to distribute forms on many different scales. The Network city emphasizes pedestrian paths forming a network of connected urban spaces, and protects those paths from encroachment by vehicular traffic. It also offers integral connectivity between the campus and the city outside. The special requirements of a campus give it even more urgent pedestrian needs. Every building needs vehicular access, but that must take second place to the pedestrian connectivity.

An obsession with mono-functional zoning often forces all student dormitories on a campus to be clustered together, while all administrative functions are housed in a single, imposing building, etc. Yet functional segregation does not produce an ideal learning environment, as it works against mixing and compactness.

The departmental pattern (Oregon Pattern 12 given above) points to a pragmatic approach that has a major influence on planning morphology. Whereas it is standard practice to segregate academic departments into separate buildings, that never works in practice. Suppose the “Chemistry Building” is funded and built. Yet by the time the Chemistry Department gets to move into its new offices and laboratories, it has either grown or shrunk in size, so it no longer perfectly fits the building. It is more practical to adopt the approach that no single building should be expected to contain a university department. Thus, it makes better sense to physically connect a building to adjoining buildings rather than have it standing apart.

Acknowledgment: Expanded from a keynote speech “Eight city types and their interactions”, 11th International Congress on Virtual Cities and Territories, Krakow, Poland, 6–8 July 2016. Published as (Salingaros, 2017).

This is part 2 in a series. Part 1.

REFERENCES

Christopher Alexander, S. Ishikawa, M. Silverstein, M. Jacobson, I. Fiksdahl-King & S. Angel (1977) A Pattern Language, Oxford University Press, New York.

Christopher Alexander, M. Silverstein, S. Angel, S. Ishikawa & D. Abrams (1975) The Oregon Experiment, Oxford University Press, New York.

Nikos Salingaros (2017) “Eight City Types and Their Interactions”, Technical Transactions – Architecture, Volume 2, Politechnica Krakowska (Krakow Technical University), Krakow, Poland, pages 57-70. http://www.ejournals.eu/Czasopismo-Techniczne/2017/Volume-2/

Links to the 10-part Salingaros campus design series:

- Welcoming open spaces

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/05/07/welcoming-open-spaces-campus... - Alexander’s Oregon patterns

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/05/16/alexander%E2%80%99s-oregon-p... - Avoiding planned isolation

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/05/30/avoiding-planned-isolation-c... - ‘Walkabout’ design with human sensors

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/06/13/%E2%80%98walkabout%E2%80%99-... - Budgeting for a fractal city

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/06/25/budgeting-fractal-city-campu... - The university campus as a microcosm of tradition

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/07/18/university-campus-microcosm-... - Why we hug the edge of open spaces

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/07/26/why-we-hug-edge-open-spaces-... - Space is experienced positively only when it is coherent

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/08/06/space-experienced-positively... - How life is influenced by physical boundaries

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/08/13/how-life-influenced-physical... - Car-pedestrian interactions and the parking ribbon

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/08/23/car-pedestrian-interactions-...