The history of urban freeways in North America has been one of inequity and induced demand. Transportation officials built and maintained in-city freeways on the presumed value of high-speed automotive travel through cities no matter the social, economic, and environmental costs. That view, still widely held in many Departments of Transportation nationwide, is increasingly being contested as the legacy of these highways has indisputably led to inequitable damage in communities and induced demand only making traffic and pollution worse. Now, with many of these hulking, burdensome highways reaching the end of their useful lifespans, communities are looking for alternatives to costly highway repair and expansion. The ten campaigns in this report offer a pathway to better health, equity, opportunity, and connectivity in every neighborhood, while reversing decades of decline and disinvestment.

Freeways Without Futures 2023 is the first to coincide with acknowledgment from the federal government of the inequitable and harmful impacts of urban highway construction. Financing for the first round of funding through the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program awarded $185 million in grants to 45 projects to construct and plan for transformative community-led solutions such as capping interstates with parks, reclaiming sunken highways for housing, constructing Complete Streets, and creating new community connectivity through public transportation, bridges, tunnels and trails. Five of the campaigns featured in this report received funding from US DOT for planning and studies to further augment the work already being done in their local communities to make their visions of a freeway-free future a reality.

Even more, the Neighborhood Access and Equity Grant Program will open funding applications in Spring/Summer 2023, and these funds can be used to improve neighborhood walkability and ease access to transit and micro-mobility options for millions of people around the country. In total, there is over $4 billion in federal funds for local governments and residents to put towards actions that can dismantle the harmful infrastructure that currently besieges their communities. While it remains to be seen how this funding will be used, a number of campaigns featured in this report applied for Reconnecting Communities funds and hope to use this money to remove their own futureless freeways. Media inquiries: Contact Lauren Mayer.

- Interstate 787, Albany, New York

- Interstate 35, Austin, Texas

- US 40 Expressway, Baltimore, Maryland

- Interstate 794, Milwaukee, WI

- State Highway 55/Olson Memorial Highway, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Interstate 94, Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Interstate 980, Oakland, California

- State Route 99, Seattle, Washington

- Interstate 244, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- US Route 422, Youngstown, Ohio

Constructed during the urban renewal efforts in the 1960’s, Interstate 787 was part of the larger Empire State Plaza project which demolished 98 acres of thriving neighborhoods, homes, and businesses in the City of Albany, creating a state office complex with a highway to easily take people in and out of the city. In addition to losing thousands of homes and businesses to the overall project, Interstate 787 architecturally cut off Albany from the riverfront and even more dramatically segregated the redlined neighborhoods of the South End and Arbor Hill, exacerbating the lack of investment and resources that redlining created for the neighborhood’s residents, who were predominantly people of color.

Albany Riverfront Collaborative was created as a grassroots organization to conceive of a city without I-787 while centering the needs of the current communities as the process moves forward. Since the first formal meeting in early 2021, the ARC has created conceptual designs and renderings, produced an internationally award-winning video, completed an economic impact analysis and in 2022, was instrumental in receiving a $5 million formal commitment of funding for the NYSDOT to conduct a feasibility study with DOT issuing the associated RFP in August 2022.

As part of the Collaborative, there is a Community Engagement Committee that is creating a full community engagement plan. Social justice has been central to the Collaborative since its inception as the purpose for this initiative is not to price out any impacted resident, but rather to give residents the neighborhood, resources, and connections that they should have had before the highway isolated them. A large part of the Community Engagement Committee is to ensure residents’ voices are heard and are part of the entire process. The Communications Committee is also posting information regularly to keep the city’s residents informed and up to date with progress and opportunities to participate.

Removal of Interstate 787 would help to heal the divisions created when this road tore apart the core of Albany. Removal would reduce noise and air pollution with slowed and reduced traffic, reconnect the historically underinvested North and South End neighborhoods, and improve economic vitality. Even more, calls for I-787’s removal overlap with the cleanup and restoration of the Hudson River which more people are utilizing through boating and kayaking, and on the shore through walking, bike riding, and fishing. Connecting the heart of the city with the riverfront will drive many different kinds of economic activities, and support transitions to multi-modal movement into and throughout the city. Albany is also the capital of New York State, and the highway is currently creating actual barriers to access for the heart of the Capital and the many people that go there. Highway removal would allow easier access to the Capitol and other state buildings that can give residents better access to jobs and places of business while allowing businesses the opportunity to take advantage of the economic driver that comes from being the NYS Capital.

Albany Riverfront Collaborative is currently asking for community input. While they have a few ideas for what to do with I-787, it is vital to long-term success that the residents and the communities that will be impacted drive the design and conversation. This is not an outreach program but a co-creation program. Several proposed ideas are providing discussion points, and interest. They include the aim to bring the roadway back to scale as an at-grade boulevard, reconnect long-divided neighborhoods by restoring the city’s street grid, reconnect the entire city to the river, create parkland both in the city and along the waterfront, and release 92 acres of unfettered land for other uses. The NYSDOT feasibility study may also illuminate other solutions to bring people into the city without needing to bring in as many cars.

Removing this highway is a step toward repairing the injustices of redlining and underinvestment. Affordable housing is highly important to the elected officials in the City of Albany as well as to the Governor’s State of the State goals, and these officials are strong partners for ensuring that there is economic growth while also working to ensure that residents can stay in their community. As Albany owns much of the land currently in the highway’s footprint, there is ample opportunity for new residential and commercial development. Neighborhoods that have been choked off from resources and investment could begin to reconnect and thrive with the removal of Interstate 787. No matter the final design, Albany Riverfront Collaborative is striving to center the needs of the current community, as the answers MUST come from the impacted communities.

Interstate 35 was constructed through Austin in the 1950’s in the right-of-way of the original East Avenue. Its location reinforced the racial segregation that began with Austin’s 1928 Plan forcing minority communities to be concentrated in East Austin through racist zoning, policies, and redlining. Today, I-35 slices through Austin’s urban core, creating a barrier between neighborhoods. There are multiple areas where walkable, older neighborhoods adjacent to I-35 are disconnected from each other because the highway lanes are impossible to cross, bridges and underpasses are infrequent, and both bridges and underpasses have narrow (if any) sidewalks right next to high-speed traffic. In a typical year, around 26 percent of Austin’s traffic fatalities occur in the I-35 corridor.

In 2012, TxDOT recognized that the I-35 infrastructure was nearing the end of its lifespan and warranted replacement, and initiated the current proposal, which would expand 28 miles of the highway from 12 to as many as 22 lanes in some places. TxDOT has split the project into three segments, one of which has already officially broken ground and is the subject of a lawsuit. TxDOT plans to rebuild frontage roads and general-purpose lanes, add managed lanes and auxiliary lanes, and rebuild existing bridges in the urban core. Because of this project’s massive scope, especially in Austin’s urban core, the discussions about what to do with I-35 represent a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reconnect neighborhoods that enjoyed walkability and access before I-35 was constructed.

There are two local campaigns, Reconnect Austin and Rethink35, advocating for alternatives to TxDOT’s I-35 expansion plans. These local campaigns have calculated that there are 136 acres of land that could be repurposed in this economically productive and rapidly growing capital city.

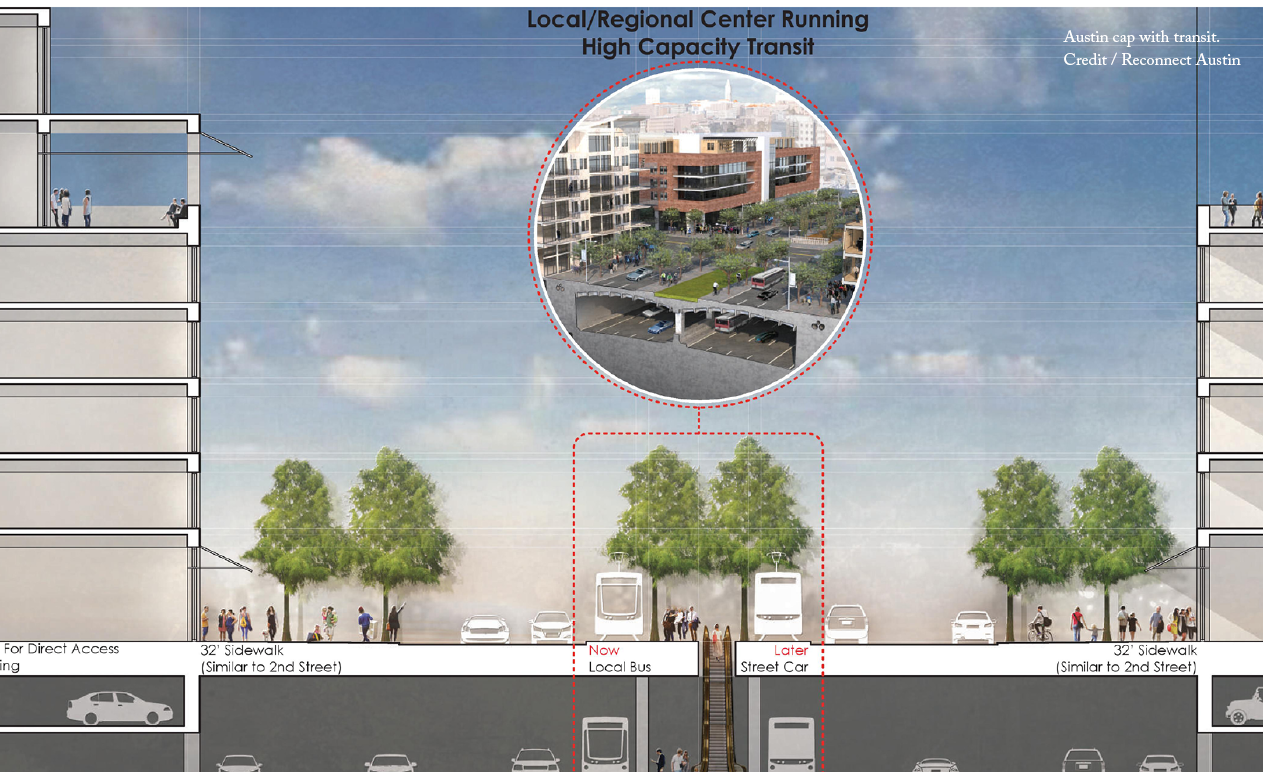

Reconnect Austin has worked for over a decade to advocate for a cap over this major interstate. They have pushed for reducing the number of lanes, narrowing the right of way, and creating new land where frontage roads used to be, which would allow new development and spur economic growth. They have also advocated for the use of modern design standards and slowed vehicular speeds, plus doing everything possible at the surface to create an urban and humane environment. Reconnect Austin has continued to be a voice in the community for the alternative vision of depressing I-35 downtown and capping it with a new, walkable boulevard by giving presentations to various groups and organizations, educating the public on the alternative plan’s benefits, and sharing the word state- and nation-wide about their efforts. In January of 2022, TxDOT took their own Alternative 3 design and modified it substantially based on community feedback and is now proposing a boulevard through downtown and at the University of Texas, with the opportunity to cap about 21 acres. While this is a big step forward, the updated plan still falls well short of the Reconnect Austin vision.

Rethink35 was founded in the Fall of 2020 as a grassroots community movement campaigning to reroute non-local traffic around, not through, Austin on existing highways and then convert I-35 through Austin into a multimodal boulevard with value capture programs to prevent displacement in nearby neighborhoods and close socioeconomic gaps between communities. The group maintains that burying highways does not solve car-dependency, crashes, pollution, and climate change. They are co-plaintiffs with Environment Texas and the Texas Public Interest Research Group in a lawsuit against TxDOT, alleging that the agency has improperly segmented their planned expansion into three parts to evade more rigorous environmental review and public engagement requirements. As a vibrant and growing grassroots campaign based on a people-power philosophy, Rethink35 has started student groups at various universities and high schools across Austin; conducted outreach to residents and local organizations and businesses; held numerous protests outside TxDOT events; and testified at city, county, and state level hearings.

Because of the work of these local campaigns and others, the vision of reconnecting Austin has permeated into the language that elected officials at the city, county, and state use to describe this project, and the City of Austin has been more involved in the alternative design for I-35 than ever before. In February 2023, Austin City Council passed a resolution on I-35 calling for TxDOT to improve the project. It calls on TxDOT to treat water runoff, minimize displacement of residents and businesses, create more connectivity between East and West Austin, allow for future capping opportunities above the buried highway, and to meaningfully study the community alternatives. This is the first formal action taken by the City Council since the project was officially kicked off by TxDOT in 2020, and represents growing community dissent towards TxDOT’s proposed expansion of I-35.

Removing the infrastructure barrier that is I-35 must be accompanied by proactive measures to prevent displacement and close socioeconomic gaps in surrounding communities. Thankfully, a precedent for this is in the process of being set in Austin: In 2020, Austin voters passed Proposition A to fund Project Connect, a long-term, citywide transit plan for Austin that includes $300 million in anti-displacement funding, as well as a process for engagement to decide how that funding will be spent.

Both the Rethink35 and the Reconnect Austin proposals would restore connectivity between East and West Austin, create pleasant and walkable places, and increase the housing supply in a gentrifying city featuring rapid displacement. The ideal alternative design proposed by Reconnect Austin involves sinking all of the main lanes of I-35 and covering them with a new, narrower, pedestrian-friendly boulevard. The removal of the access roads would open up 30 acres of developable land, and additional acreage north of downtown, on which could be built mixed-use blocks with housing, offices, and activated ground floors. In addition to reconnecting the community, the Rethink35 proposal would reroute non-local traffic around town and replace the existing highway with an urban boulevard that would further reduce car dependency, air and noise pollution, crashes, carbon emissions, and induced sprawl through a major urban area, providing the opportunity for more housing through a longer stretch of the current I-35.

Improving the urban fabric through capping or removal would also invite more development in the entire adjacent area, where there is currently very little available land. Additional tax revenues from newly developed land could go toward preventing displacement, assisting residents in buying their homes, and closing the socioeconomic gaps between communities that I-35 helped widen. The Texas Transportation Institute estimates the cost to cap at $375/sq. ft (based on recent caps in Dallas). As of February 2023, TxDOT has agreed to construct a selection of caps in tandem with the expanded highway, but only if the City of Austin can pay for them.

Also in February 2023, the City of Austin's “Connecting Austin Equitably—Mobility Study” was awarded $1.12 million from US DOT's Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program to evaluate transportation, public health, equitable development, and environmental justice outcomes related to the possibility of capping parts of an expanded I-35. America Walks expressed concern over this award, stating “USDOT should leverage the Reconnecting Communities program to discourage state DOTs from literally being able to cover their mistakes in real-time.”

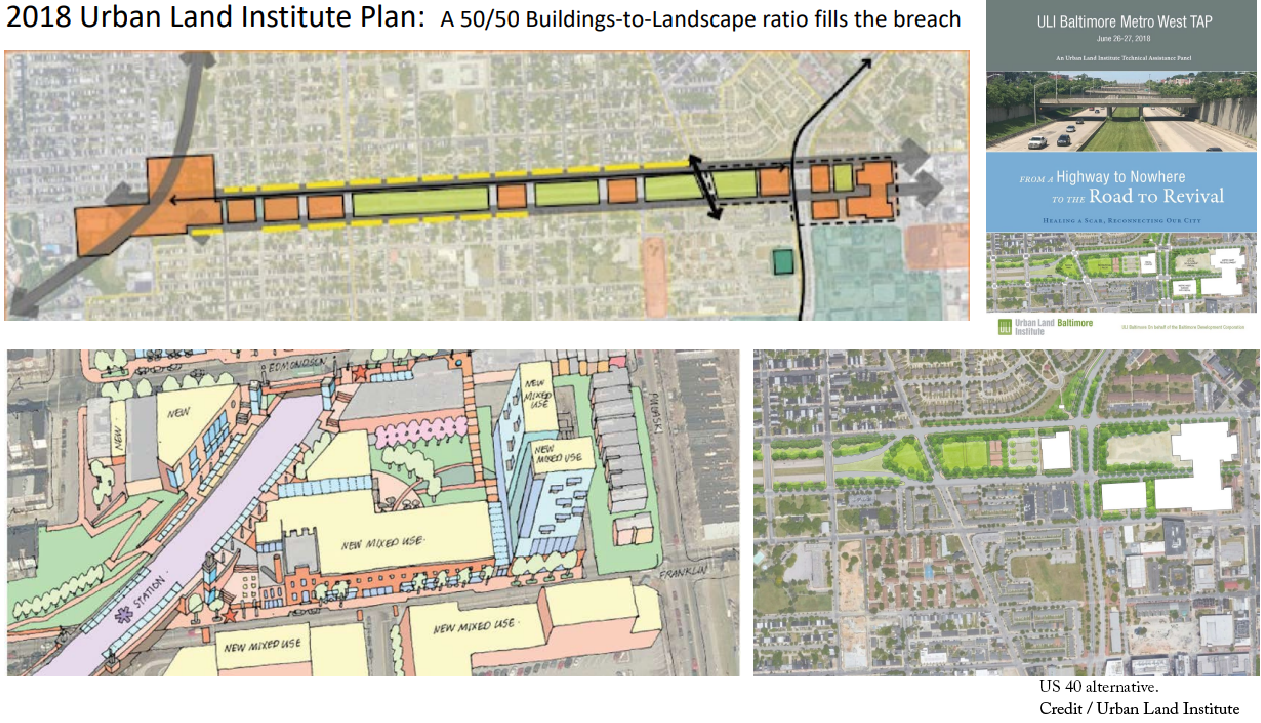

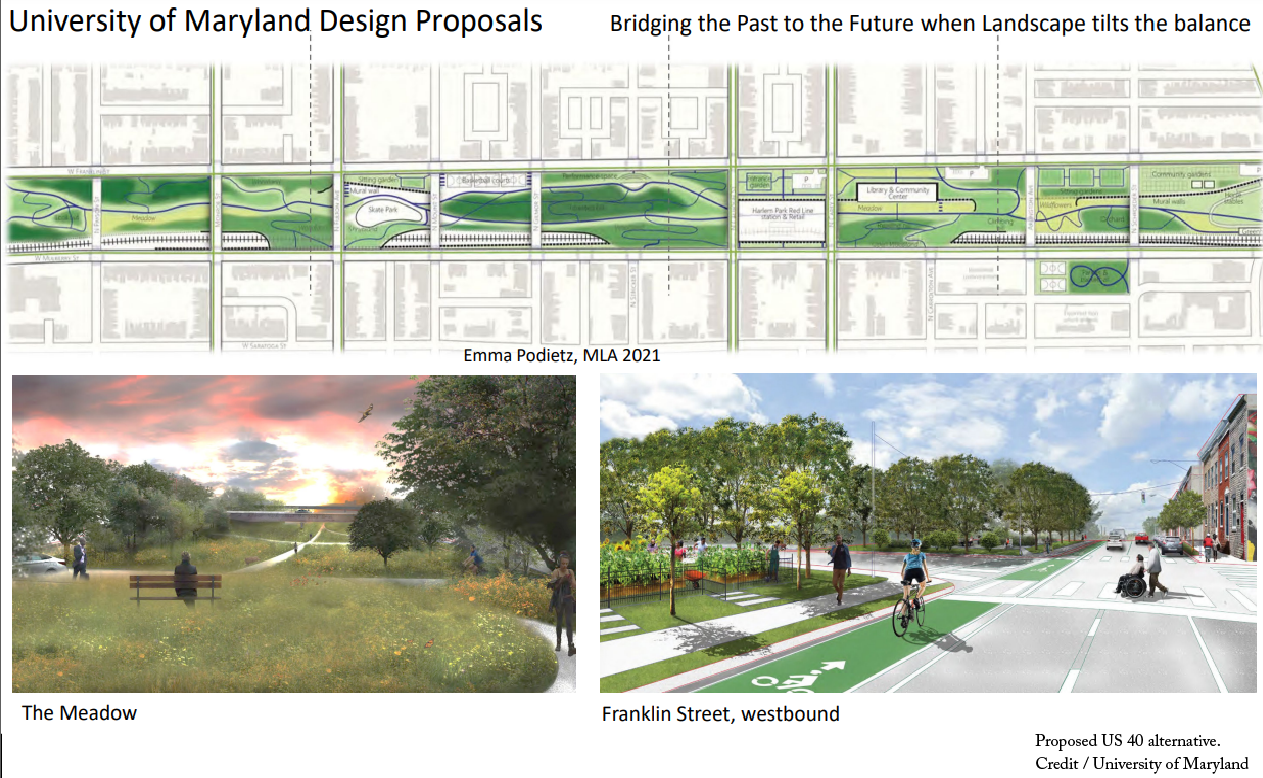

Baltimore’s infamous “Highway to Nowhere” was intended as a fast-moving connection between downtown Baltimore and the western suburbs via the beltway (I-695) and I-70, requiring the demolition of private homes and active businesses in the historically African American community of West Baltimore. Before it could advance further, construction was stopped by environmental advocates and empowered community members and only a 1.4-mile stretch of Route 40 was constructed, resulting in the displacement of approximately 1,500 residents of West Baltimore. Roughly 50 years later, the Highway to Nowhere remains both a physical barrier and scar in the community that has struggled with the injustices of segregation, property devaluation, unfair eminent domain, and intrusive highway construction as “urban renewal.” As Baltimore lost its manufacturing base in the 1970‘s and 1980’s, the neighborhoods north and south of the Highway to Nowhere faced city-wide job losses, depopulation, abandoned homes, and, in the early 2000’s, financially devastating subprime mortgage lending practices.

Baltimore’s Department of Planning and Department of Transportation have been working closely with the West Baltimore neighborhood communities since 2009 when the city proposed a new east-west 14.5-mile mass transit rail line (the Red Line), using the “Highway to Nowhere” for the westernmost alignment and proposing two local stations at Harlem Park and the West Baltimore MARC Station. The Red Line was scrapped in 2015, but now, with the availability of funding through the federal Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, the city is revisiting the results of those community outreach efforts and is again engaging the community to discuss the future of the highway.

In September of 2022, the Baltimore Department of Planning in partnership with the Baltimore AIA Urban Design Committee organized a public forum as part of an effort to listen to concerns and gain consensus from a city-initiated effort to apply for a planning grant through the Reconnecting Communities grant. The forum provided stakeholders a platform to see and present ideas that have already been developed over the years. Participants discussed past and ongoing grassroots organizing efforts, development opportunities, academic work focused on the Highway to Nowhere, planning studies, and Baltimore City’s current efforts to obtain federal funding through a Reconnecting Communities Grant.

All proposals address the communities’ desires for improved connections with nature, environmental and individual health issues, job and job training opportunities, education and recreational needs, and the transformation of outdated transportation infrastructure into green infrastructure and economic development for a healthy city. Potential federal funding for a green infrastructure project via removal of the Highway to Nowhere has emboldened community leaders in these underserved areas of the city to resurrect the abandoned 14.5-mile Light Rail proposal in an effort to reinvigorate communities and give hope for more just and equitable development.

West Baltimore United received $2 million from US DOT’s Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program grants to study the possibility of removing, retrofitting, or modifying the impacts caused by the construction of the US 40 Expressway. This planning grant will reconnect historically Black communities by addressing inequities and improving safety, access, opportunity, and innovation in West Baltimore. Partnerships and support for this project include transit providers, environmental agencies, local elected officials, and non-profit representation. The planning process is a community-driven vision with focus on community stabilization policies related to both affordable housing, community benefits agreements, disadvantaged/minority/woman-owned business enterprise goals for projects, and more.

Well in advance of transforming the Highway to Nowhere into a new, sustainable environment, the City of Baltimore has put into place a policy that recognizes the potential for gentrification and give current renters and homeowners protections, such as rent control, community stabilization efforts, and property tax relief.

The availability of financing for highway removal from the federal government is a catalyst for addressing the long-term impacts of the Highway to Nowhere. The planning, research and outreach efforts associated with the Reconnecting Communities Grant will establish programs and estimate the costs. Even more, with federal funding to remove and reconfigure the Highway to Nowhere, increased access to public transportation alternatives will unlock additional funding opportunities for education and skill training, greater access to a variety of job locations, increased entrepreneurial start-ups, corporate investment, and community enhancements.

I-794 was constructed as part of the downtown highway loop that was never completed and separates Downtown Milwaukee from one of its premier neighborhoods and Lake Michigan. The highway damaged the Third Ward neighborhood, which has seen a resurgence and is one the fastest growing census tracts in the State of Wisconsin. While this spur has never seen the traffic counts it was intended to carry, WisDOT views it as an important piece of infrastructure and an upcoming 2023 project will repair a portion of the highway for $300 million.

The Rethink 794 campaign was formed following an urbanist meet-up in March 2022 about the highway, and the idea to rethink I-794 as a boulevard was warmly received. Between that meeting and the campaign’s popularity on social media, Rethink 794 has started discussions with the community and city officials.

The campaign has galvanized support through the ongoing Downtown Plan Update, where grassroots supporters have asked the city to study I-794 as a boulevard and to make it the locally preferred alternative. Milwaukee's mayor has previously spoken in favor of rethinking the highway but has received pushback from WisDOT. Behind the scenes Rethink 794 have been engaging with WisDOT, and the campaign was asked to join the main project stakeholder committee. WisDOT has committed to studying a boulevard alternative, but doubts remain about whether it will receive a fair shot.

If I-794 was removed, two major neighborhoods would be reconnected. The project sits on 32.5 acres of land, some of the most valuable in the State of Wisconsin. Both of the adjacent neighborhoods (Downtown and the Third Ward) have experienced growth, but many vacant lots and parking lots still flank I-794. With the highway's removal, these sites will be more desirable and should lead to more development in Milwaukee's (and Wisconsin's) densest, most transit rich area. Additionally, it would allow for the creation of parks and easier access to the Lakefront which could increase tourism to the Downtown.

Since the land is public, the city could control what is built on these sites, which could lead to more affordable housing in a location that is transit rich and in need of more workforce housing. Approximately 25% of residents walk to work in this area, which advocates note is very dangerous for walking/biking in its current state. 30% of residents around the project area are people of color, considerably higher than the state average, so the project would have serious equity impacts as well.

There is also precedent for highway removal in Milwaukee. The Park East removal in Milwaukee is largely viewed as a success and was removed for ~$80M in today's dollars. While this project is different from the Park East, removal is certainly cheaper than the $300M planned for repairs.

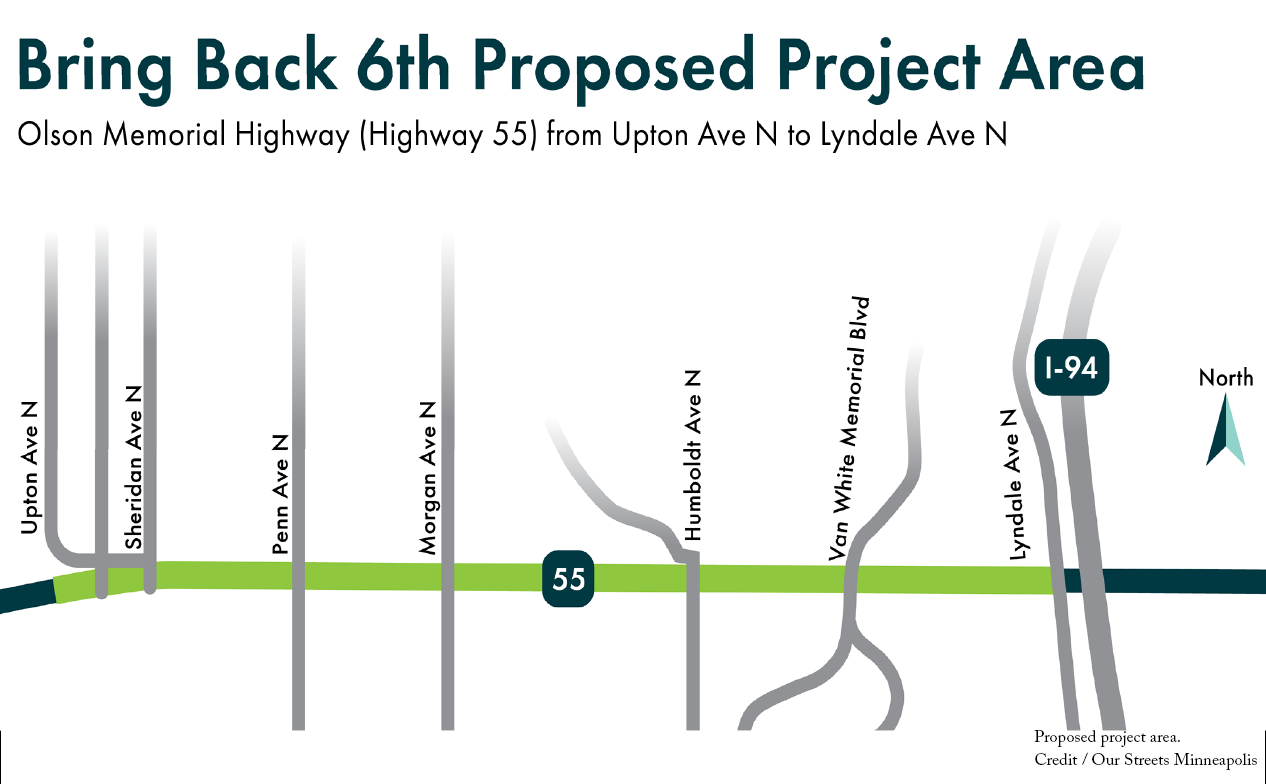

State Highway 55/Olson Memorial Highway was once a vibrant, predominately Black-owned business corridor called 6th Avenue North. Often referred to as the “Beale Street” of Minneapolis, 6th Avenue North was home to a vibrant cultural and music scene. The area was also a cornerstone of the Jewish community in Minneapolis and was one of the few neighborhoods that was open to immigrants and people of color. Construction of the highway was approved in 1933 and by the end of the 1930’s, hundreds of businesses and homes along the route were completely destroyed and replaced with a wide highway cutting through the neighborhoods. The highway was then expanded in the late 1950’s, further displacing homes, gathering places, and neighborhood businesses. This destruction displaced hundreds of homes and businesses and destroyed generational wealth. The highway was followed by continuous disinvestment in the North Side. Nearby neighborhoods continue to face economic hardship, soaring rent prices, and lack of transportation options.

Today, the highway divides the Near North community and presents a safety risk with its 6 plus lanes of vehicle traffic. Unlike other highways on this list, this route is a very wide surface highway often called a “stroad” because the highway is not separated from the street grid and the numerous high-speed intersections make it prone to deadly crashes. As a result, the corridor is included on the high injury street network, and the intersection of Olson Memorial Highway & Lyndale Avenue N has the city’s highest rate of incidents. In the past decade, there have been dozens of crashes on Olson Memorial Highway that have resulted in death and severe injury. The Bring Back 6th campaign is a grassroots movement that seeks to remove the highway and restore 6th Avenue N along an area that stretches a little over a mile from Lyndale Avenue to Upton Avenue.

The Bring Back 6th campaign launched in November 2021 as a partnership between the Harrison Neighborhood Association and Our Streets Minneapolis. The initial effort was to address commitments by Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis to incorporate safety improvements into the Blue Line Light Rail extension project, which was proposed to go through Olson Memorial Highway. After the proposed route was changed to another corridor, no safety improvements were made, and a few hundred immigrant families were displaced due to speculation. Thanks to the research into the 90 years of intentional harm on the Near North Minneapolis community, the two phased approach was launched to address both near-term safety needs and the almost near-century worth of harms. The campaign organizes by empowering community members to contact their decision makers and put pressure on them to make improvements to the highway and, ultimately, replace it with a restored avenue. The campaign is working to design plausible solutions for the corridor in two phases. The first phase is near-term safety improvements that can be implemented immediately by MnDOT and the City of Minneapolis. The second phase is a full reconstruction of the walkable amenities, culture, and economy that used to exist along 6th Avenue North.

The goal is to both address immediate community needs and encourage the community to visualize a better future. Both phase 1 and phase 2 of the Bring Back 6th vision were developed in close partnership with the Harrison Neighborhood Organization, incorporating ideas from the community, and promises that were made and not kept by the City of Minneapolis, and Hennepin County. Households near Olson Memorial Highway are 3 times less likely to own a car than the rest of the Twin Cities region, and pedestrian safety is a major concern raised by the community. Phase 1 would reduce the number of vehicle lanes and lower the speed limit, with designed crosswalks that support the talent of local artists and increase pedestrian visibility. A new bike lane would connect these neighborhoods to the rest of Minneapolis.

Phase 2 addresses the long-term racial and economic harms of the highway. Two-thirds of renters in the Harrison neighborhood are cost burdened. Many community members speak about how they have to leave the neighborhood to access a grocery store, restaurants, or entertainment. The Bring Back 6th campaign aims to repair the historic harms and restore these walkable amenities. The community benchmarks would ensure that the necessary policies are implemented to ensure that this transformation does not result in displacement and that the benefits are prioritized for existing community members.

Bring Back 6th co-hosted “Imagine 6th Avenue North” in May 2022. This interactive event partnered with local neighborhood organizations, artists, and entrepreneurs, and engaged people on what the corridor could look like without the highway. It featured the Bring Back 6th Mobile Museum, which illustrates the history of the corridor before and after the highway was built. Additionally, the campaign team has developed materials to visualize and explain the disproportionate harms of Olson Memorial Highway and regularly hosts virtual community forums to provide campaign updates and call on decision makers to make a public commitment to supporting the Bring Back 6th vision. At the first forum in 2022, over 100 community members attended.

In a community that has already been displaced by transportation infrastructure, it is especially important that any future projects prioritize the well-being of existing residents and that intentional policies are implemented to prevent gentrification. Our Streets Minneapolis has worked directly with the Harrison Neighborhood Association to create a set of anti-displacement policies and community benchmarks to accompany the desired transportation changes. These policies focus on preventing displacement and ensuring that the reclaimed highway land is used to increase housing and commercial space that is truly affordable and prioritized for existing residents. This would be accomplished by placing the remaining highway land in a community land trust and using it to build affordable housing, including new public housing, as well as community-owned commercial space to restore walkable access to small businesses and daily needs. The goal is that this housing and commercial space would be prioritized for existing residents and that programs would be created to help people access the necessary training and capital to start or expand a business.

The broad public support behind the Bring Back 6th campaign has resulted in the Minnesota Department of Transportation announcing a reconstruction of Olson Memorial Highway in 2027. In fall of 2022, MnDOT installed some temporary safety improvements and has committed to making additional safety and multi-modal improvements in 2023. Restoring 6th Avenue N will reduce ongoing maintenance costs and produce benefits that far exceed the increased construction cost associated with highway removal. These benefits include:

- New affordable housing

- Reduced traffic deaths and life-altering injuries

- New locally owned businesses and increased tax revenue

- New parks and community gardens

- Improved transportation access

- Improved air quality and reduced health impacts

- Reduced greenhouse gas emissions

Planned and built in the 1960’s, I-94 tore through the fabric of Minneapolis and Saint Paul neighborhoods. Thousands of homes and small businesses were bulldozed to make way for a massive, football field-wide freeway trench, creating scars across the city landscape. This devastation disproportionately impacted communities of color. Eighty percent of Minneapolis Black residents lived in the neighborhoods where I-94, 35W and Highway 55 were routed. In Saint Paul, 6,000 people and hundreds of businesses were displaced by I-94, the majority of which were located in the Rondo neighborhood, home to eighty percent of the City’s Black residents at the time.

The highway continues to divide communities along the corridor and is a major contributor to pollution. Air pollution along the corridor is nearly three times worse than what is deemed unhealthy by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA.) Ninety-four percent of the project corridor has been identified by the MPCA as “an area of concern for environmental justice.”

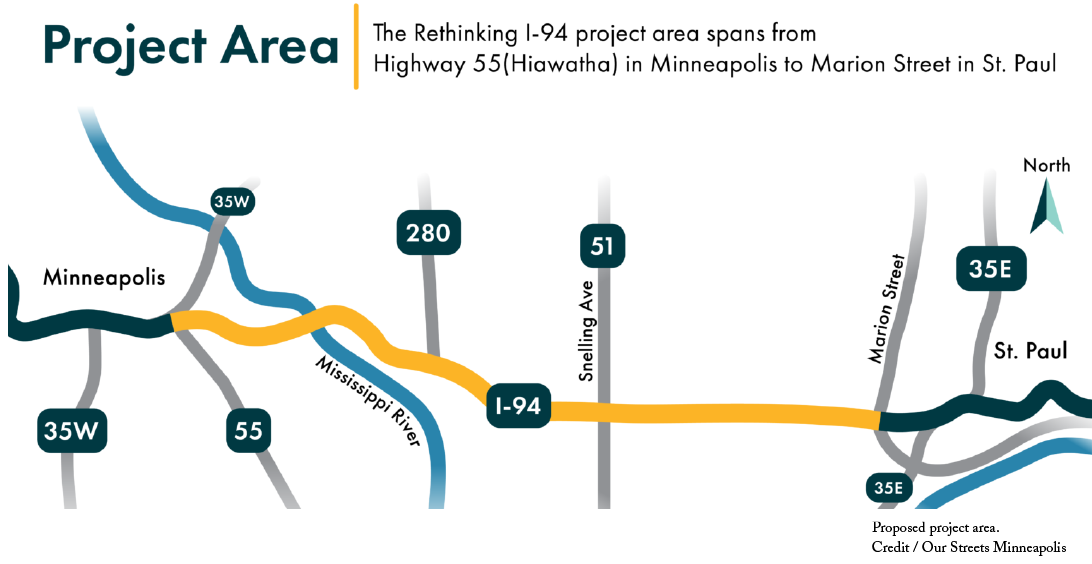

Now, I-94’s pavement, bridges and retaining walls are nearing the end of their useful life, and the segment between downtown Minneapolis and Saint Paul is due to be reconstructed. MnDOT has created the “Rethinking I-94 project” to determine the future of this corridor. This project is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to repair the highway’s historic and ongoing harms and reimagine the corridor to prioritize the health and well-being of the tens of thousands of people who live, work, and go to school near it.

The Twin Cities Boulevard, supported by Our Streets Minneapolis, is a growing community vision to replace the 7.5-mile section of I-94 that makes up the Rethinking I-94 project corridor with a multimodal boulevard, return the surrounding land to neighborhoods and fulfill calls for reparative justice along the corridor. The Twin Cities Boulevard would fill in the I-94 trench and replace it with an at-grade, multi-modal boulevard, including rapid transit, bikeways, linear parks, and reclaimed land for community guided housing and business development. The vision includes a robust set of policies and community benchmarks focused on housing, anti-displacement, community stewardship, and equitable investment with the aim of ensuring that the benefits of highway removal are prioritized for existing residents and those who have been disproportionately impacted.

Public engagement and community consent is a key aspect of this project. Rather than push a completed vision on the community, the Twin Cities Boulevard campaign seeks to empower communities along the highway to determine what they want to see in their neighborhoods. The campaign has also partnered with other community groups to host events to highlight the Rethinking I-94 project, the highway’s impacts and the Twin Cities Boulevard campaign goals. This included a group bike ride with BF50 Indigenous Health and a highway health impacts forum with Health Professionals for a Healthy Climate.

Since launching in February 2022, the campaign has successfully petitioned MnDOT to issue a statement acknowledging the harms of I-94 and committing to including a highway to boulevard option in the upcoming project alternatives. Our Streets Minneapolis is advocating for state funding to go towards a feasibility study of a highway to boulevard conversion on Interstate 94. This study would help understand the climate, traffic and economic impacts on Rondo and other Minneapolis and St. Paul communities along the project corridor. Concurrently, Our Streets Minneapolis is collaborating with the Mapping Prejudice Project, the University of Minnesota’s Heritage Studies and Public History program, and conducting story collection and engagement along the corridor. This work helps elevate stories from the other neighborhoods and communities that were impacted by I-94.

One such story is the Rondo neighborhood. Reconnect Rondo, an organization focused on a smaller portion of the impacted community in St. Paul has received $2 million from USDOT's Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program grants to study the planning and development of an African American Cultural Enterprise District and associated Land Bridge to restore and reconnect the Rondo neighborhood. The idea of a Black Cultural Enterprise District in the Rondo neighborhood is a critical part of Reconnect Rondo’s work as a lot of Rondo residents feel strongly about a reparative justice vision for the neighborhood. However, the land bridge project is for .5 miles and the MnDOT project corridor is 7.5 miles meaning there are more opportunities to address this 150-year history of harms, open the door for solidarity between both cities and, in addition to Rondo, give other neighborhoods the same ability to uplift their histories, and reimagine their communities reconnected and redeveloped with a boulevard conversion.

A highway to boulevard conversion would allow for meaningful redevelopment of the entire corridor community, and help remove a primary source of these historic harms: car traffic and pollution. This conversion would set up both Rondo and all neighborhoods along I-94 for economic redevelopment and eliminating the long term threat of the climate and health impacts. The removal of I-94 would help to reverse the impacts of the racist and classist policies that dictated the highway route and shaped the current economic and environmental realities of all the neighborhoods along the corridor. Removal would impact more residents, and better connect them with economic opportunity. The resulting reconnected street grid, new housing and local businesses would help address the need for upward mobility, and more walkable neighborhood amenities. Twenty-eight percent of households within the project corridor do not have access to a car. The land freed up by highway removal could also be placed in a community land trust so that impacted communities could determine the future of their own neighborhoods. Highway land would be replaced with truly affordable housing and community owned commercial space that is prioritized for existing businesses and would-be entrepreneurs.

The broader vision of full highway removal and the federal government’s recognition of a land bridge to repair harms in historically Black communities speaks to the momentum of acknowledging highway harms in the Twin Cities and the multiple approaches to addressing historic harms.

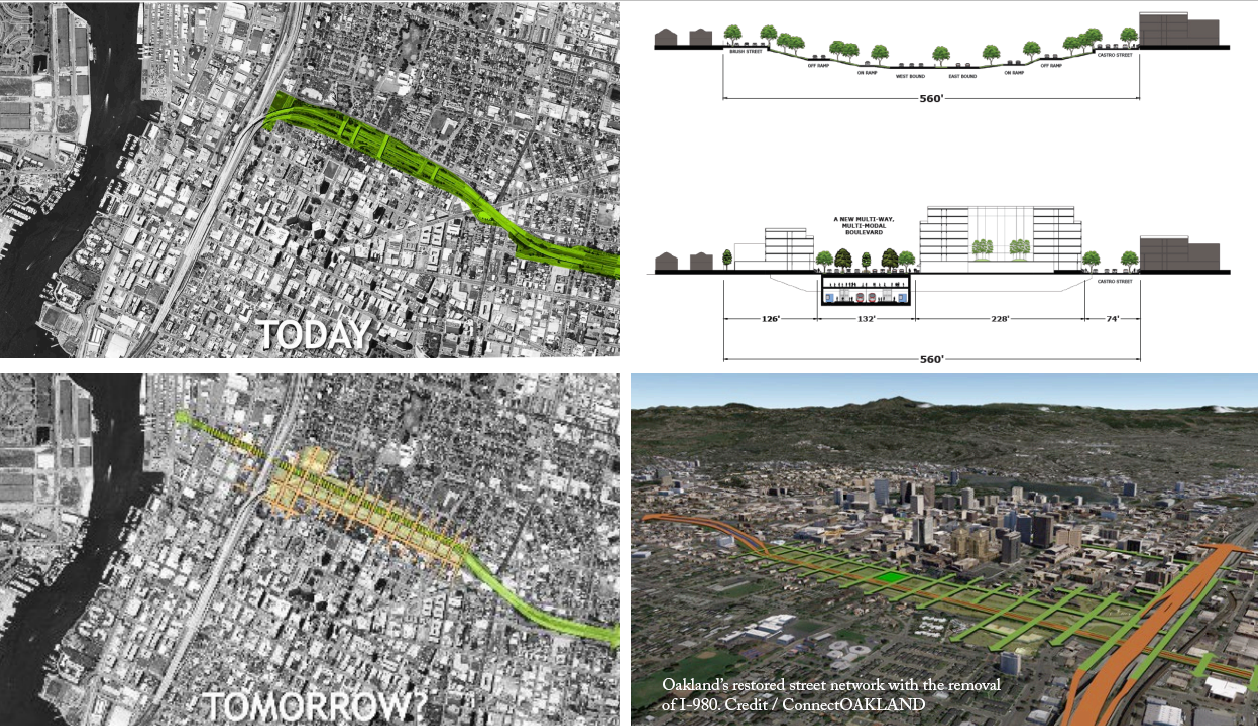

The construction of Interstate 980 began in 1962 but stalled several times due to lawsuits that cited the significant environmental harms and negative housing impacts of the project. Even though the project was halted, a portion of the right-of-way had already been cleared, leaving a no man’s land separating parts of primarily Black West Oakland from the rest of the city. In 1977, the city restarted the construction of I-980 but residents were able to get some concessions from the city in the form of new housing and rent protections. Some of the houses in the highway’s path were even relocated as part of the construction, but the freeway still disconnects West Oakland from the downtown and completely surrounds the community.

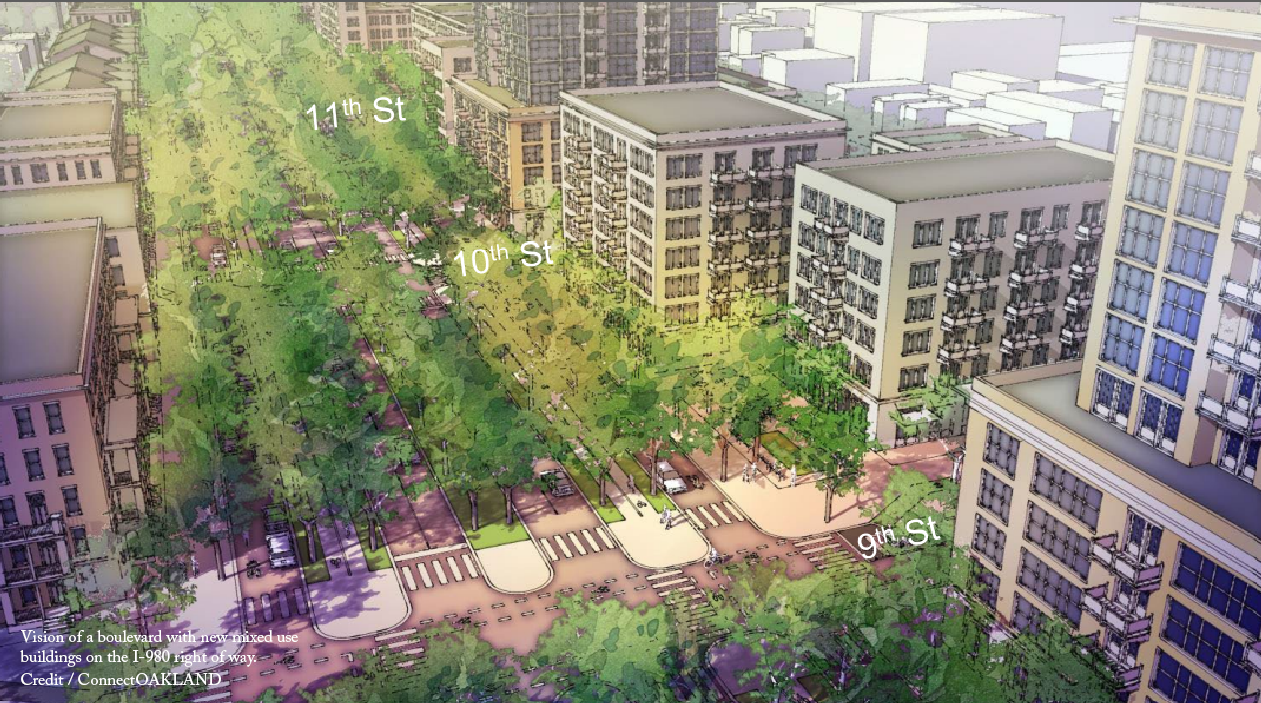

Now, as I-980 approaches the end of its designed life span, West Oakland residents once again have an opportunity to shape the future of their community as the city considers highway removal. From 2014-2018, ConnectOAKLAND worked with the community, the city, and local transit agencies to envision a future for West Oakland. In the last four years, ConnectOAKLAND has taken a more passive role, presenting at community organizations and neighborhood groups. Meanwhile, the city and Caltrans have taken a leading role in actively planning to study the removal of the freeway and to do so within a social equity and environmental justice framework.

Caltrans in collaboration with the City of Oakland has currently issued a Request for Proposals for a Vision 980 study to explore alternatives for reconnecting communities along the corridor, with an expanded focus on community integration and environmental justice to deliver more equitable outcomes.

Vision 980 Study Phase 2—Feasibility Study received $680,000 from US DOT's Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program grants to help finance the study. The plan will build on existing work, including the activities of Connect OAKLAND and other planning studies.

In addition, Link21 is studying the I-980 corridor for potential mass transit improvements. They are identifying projects that will improve train connectivity in the 21-county Northern California Megaregion, and a critical step towards a better train network is the construction of a second underground train crossing of the San Francisco Bay. Link21 has selected the I-980 corridor and West Oakland as a potential place for the construction of a second transbay tunnel to extend BART.

With support from the City of Oakland, Caltrans, Link21, and the federal government, the removal of I-980 could reconnect up to 12 streets between the neighborhoods and downtown and create approximately 17 net new acres of publicly controlled land that is either directly above or within a quarter mile of a regional transport station. The stock of housing in West Oakland is already increasing exponentially in value so a project of this scale that involves thoughtful and thorough community engagement should provide meaningful upfront planning to decrease displacement and find strategies to improve the lives of those in the surrounding communities.

South Park is a unique and beloved neighborhood that could not be mistaken for any other in Seattle. A majority of South Park residents are people of color and about 25 percent are recent immigrants. It has a long history of being home to immigrant communities and, as a result, the neighborhood was redlined in the 1930’s. As was often the case in redlined neighborhoods, State Route 99 was built in the 1950s and 1960s to divide and displace, rather than to serve the South Park community. Today, community residents contend with a dark underpass containing a narrow sidewalk bordered by a constant stream of semi-trucks – the only on-grade crossing point throughout the entire 1.5 mile stretch of highway that divides South Park in two. Living near highways has been shown to be very harmful to health and well-being, especially for youth and the elderly. The impacts of the highway combined with other challenges such as industrial pollution cause South Park residents to have a thirteen-year lower life expectancy than residents of other Seattle neighborhoods. South Park also has the most youth per capita of any neighborhood in the city, and every place where neighborhood children congregate—the elementary school, two parks, the library, and the community center—is directly adjacent to State Route 99. In addition to pollution and health impacts, the highway also causes many public safety concerns and makes it difficult to walk or bike in the neighborhood.

Reconnect South Park is a community-led effort to rethink Highway 99 through the neighborhood. Up until this year, Reconnect South Park has been a small volunteer-led effort punching above its weight. Volunteers have attended festivals and events with a scale model of the highway to have conversations with other neighbors about the effort. There is support from local public officials to study potential changes to the highway, and $600,000 was allocated from the state legislature to the City of Seattle for a two-part technical feasibility and community visioning process. A convening committee comprised of a cross-section of local residents, workers, organizers, and business people came together to advise the City on how to support community efforts with this funding, and are now developing a community-led engagement plan. The community engagement and visioning process will guide the technical studies, determining the priorities and objectives for the analysis of current conditions and future alternatives. Reconnect South Park has formed a large coalition of local, regional, and national community-based and nonprofit organizations. It has also been the focus of several university classes and design studios and has secured significant local media coverage of the effort.

Reconnect South Park recently received $1.6 million from US DOT's Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program to fund more in-depth planning studies and support the creation of an Equitable Development Plan that will put forth community-informed anti-displacement strategies to be implemented alongside any changes to the highway. The technical studies will examine multiple potential futures, including a full removal of SR-99 through South Park.

Highway removal would free up 44 acres of much needed land for equitable development opportunities, such as community-owned affordable housing, markets and small businesses, childcare and educational space, and industrial business incubators. The street grid could be reconnected and allow residents to easily walk and bike through their neighborhood. A divided community could rebuild ties with neighbors. The small, fragmented, and unusably loud green spaces could connect into one larger park to provide youth with a safe place to play and all residents with better connection to nature. Even more, South Park youth would not have to grow up knowing they would live 13 years less than the kids in other neighborhoods because one of the largest contributors of air pollution in the neighborhood would be gone.

Removing Highway 99 would also improve walkability to businesses on either side of the highway, including South Park's commercial core on 14th Ave. S. In addition to reconnecting the residential neighborhood and businesses, the highway removal would free up 28 acres of industrial land in an area that has the potential to be severely impacted by sea level rise. This land could be used for relocation strategies and for nature-based resilience infrastructure like green stormwater infrastructure and floodable open space that could protect the land from flooding and help clean adjacent waterways.

The community-led visioning process will feature extensive outreach and engagement to ensure that all constituencies are heard. An Equitable Development Plan will be developed alongside the Community Vision Plan and will be composed of community-generated strategies for wealth-building and anti-displacement that would accompany changes to current conditions. The technical studies will allow the community and local agencies to compare the potential mobility, public health, environmental, and safety impacts of different solutions, including a full removal. The community will then develop a future vision for this corridor that addresses key priorities such as affordable housing, safety, health, and usable green space.

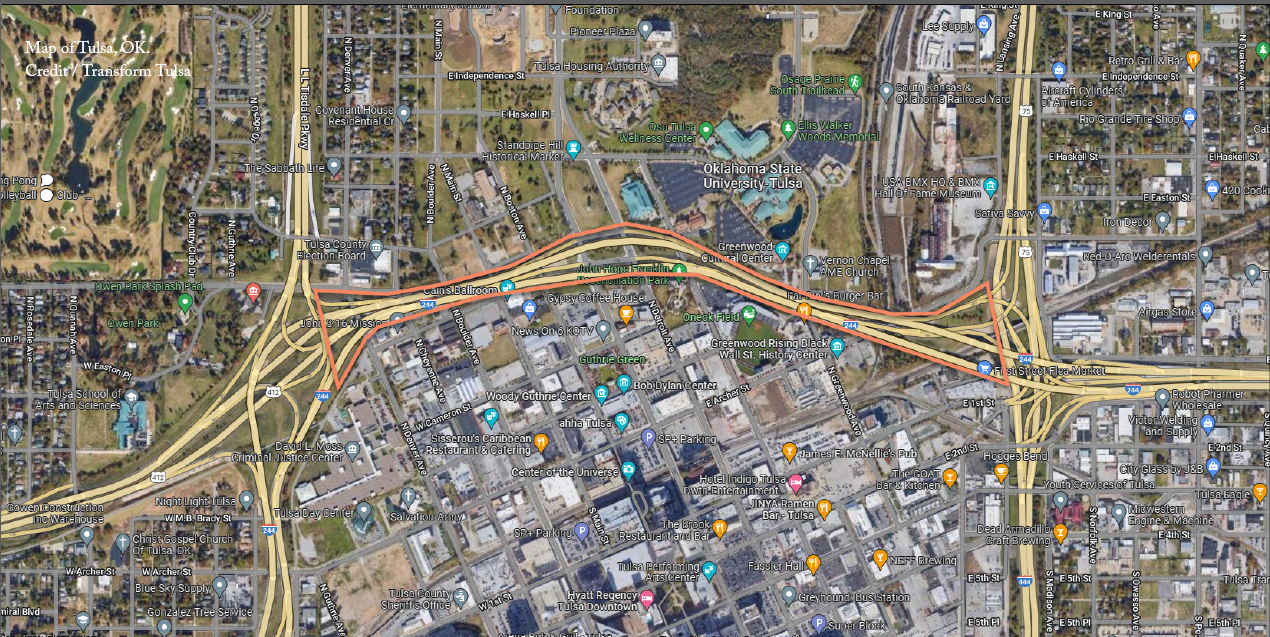

Interstate 244 runs directly through Tulsa’s Greenwood district, the historic center of the city’s Black community once famously known as ‘Black Wall Street.’ In 1921, a mob of white Tulsans, provoked by misleading newspaper headlines, descended upon Greenwood, killing at least 300 people (but likely many more) and destroying the 2019 equivalent of more than $32 million worth of property. Greenwood’s Black community quickly reestablished itself and returned even more triumphant as the term ‘Black Wall Street’ was given to the rebuilt neighborhood after the massacre, only to be razed again decades later by highways and associated urban renewal. The businesses in the I-244 (northern leg of the IDL—Inner Dispersal Loop) path were razed and either all together closed or relocated further away from downtown and away from their traditional customer bases. In 1942, Greenwood was home to 242 Black-owned businesses spread over 35 square blocks. The highway reduced that number to only a handful, most situated on the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue, which local attorney E.L. Goodwin, Sr. helped save through negotiations on getting I-244 constructed one block north of its original plan. The construction of I-244 and urban renewal forced in excess of 1,000 residents to relocate, many of whom had homes acquired well below market value.

Transform Tulsa, Tulsa’s Young Professionals (TYPROS) Urbanist Crew, Tulsa STEPS, North Peoria Church of Christ, and numerous others are advocating for the removal of I-244 and submitted an application for Reconnecting Communities through a community-led effort independent of any government entity. The outreach effort has included some government entities including the Tulsa City Council, who voted unanimously on a resolution to seek community input on removal, and State Representative Goodwin, who completed an interim study about removing I-244 in 2021 (ODOT and the Tusla MPO INCOG attended the study hearing).

Community engagement has been heavily focused in Greenwood, greater North Tulsa, and urban core areas (the most impacted neighborhoods by I-244). A master plan for vacant land, known as Kirkpatrick Heights Master Plan area, identified I-244 as a significant barrier for development of North Tulsa/Greenwood that needs to be addressed. The area is adjacent to the northside of I-244 and a master plan on the west boundary of Greenwood was also recently completed by the City of Tulsa and Partner Tulsa (called Our Legacy project: https://www.ourlegacytulsa.org/). The community-led campaign has the support of every neighborhood organization along the highway in addition to several local and elected officials such as State House Representative Regina Goodwin.

Advocates are seeking removal of I-244 with the reconstruction of the historic street grid that existed prior to the highway in order to maximize the amount of land that would be available for redevelopment and community good. This is in opposition to some effort by the Oklahoma Department of Transportation and others who either have refused to study removal or prefer to study tunneling I-244 underground which is not a cost feasible alternative. It is imperative for Tulsa to address and repair the wrongs of its past - specifically the wrong of destroying Greenwood for a second time after the neighborhood was fully rebuilt bigger and better post-race massacre.

After removal of I-244, local advocates are also pushing for the reclaimed land to be placed into a community land trust, which is in the process of being established by organizers. The land trust is critical to ensure that the financial gains of future real estate development benefits families impacted by I-244 and urban renewal eminent domain. The land trust would also mitigate impacts of on-going significant gentrification of Greenwood and North Tulsa for current residents. A variety of ownership types can be built through non-profit development in the trust that could allow for rent to own and other types of construction not typically undertaken in private for-profit development. Advocates are also seeking the land be placed into trust based on the precedent of the canceled Riverside Expressway, which utilized the same funding as I-244. After cancellation, the Riverside Expressway was returned to Tulsa for free, allowing for the creation of River Parks, which is now one of the large public park systems in the United States. In addition, advocates are also seeking to establish land planning and form-based codes to allow for small parcel development and prioritize small and local businesses and mixed income housing.

The Oklahoma Department of Transportation has said they are willing to consider removal in long range planning, but local advocates and numerous Tulsa area elected officials are advocating for the removal to be done as soon as possible. That advocacy has resulted in community advocates being awarded the I-244 Partial Removal Study, totaling $1.6 million, from USDOT's Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program. This planning grant will support an independent feasibility study for removing a section of I-244 in the Greenwood District.

Removing I-244 would not only address historical wrongs but provide the opportunity for the construction of thousands of new residential units and over hundreds of thousands of square feet of commercial space for new businesses. At full build out, this would bring in an excess of $10 million in new revenues per year to the State of Oklahoma, City of Tulsa, and County of Tulsa from property taxes and sales taxes that can be reinvested into the area long affected by the highway and other social and economic barriers.

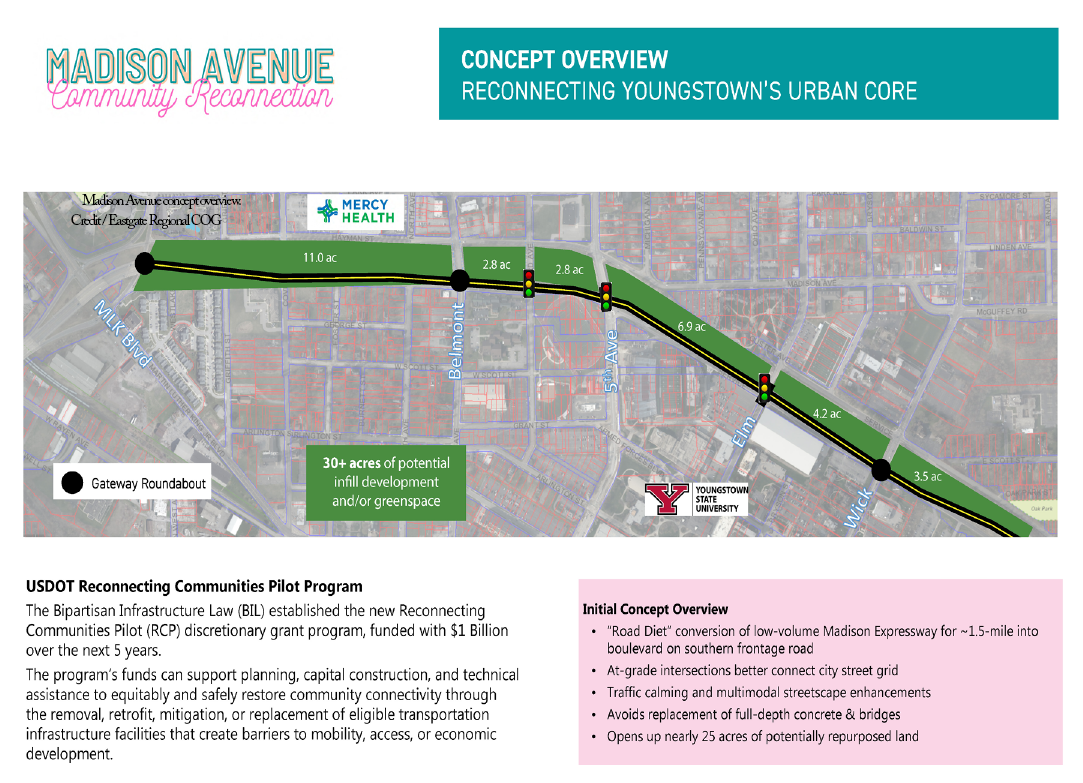

In the 1960’s, the Madison Avenue Expressway was built as a trenched limited access freeway that created an imposing physical barrier, especially for pedestrians. The construction split the original neighborhood in half which severed community connectivity and led the area’s population to decline almost immediately, as a large number of homes were demolished to make way for the new expressway and many residents moved to outlying suburbs.

The potential of highway removal was first identified in a 2020 study by the Eastgate Regional Council of Governments Belmont Avenue Corridor Plan. The Belmont Avenue Corridor Plan hosted two conversational public engagement opportunities where residents, business owners, and stakeholders from the project area were able to convey their concerns and ideas for improvement. This long term and likely expensive effort would serve to reconnect the neighborhoods that the expressway has severed by converting the expressway from a large 4 lane divided highway to a 3 or 4 lane surface street. The Corridor Plan was presented to and approved by Eastgate’s General Policy Board, Technical Advisory Committee, and Citizens Advisory Board.

With the announcement of the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, the Eastgate Regional Council of Governments is in the process of exploring the feasibility of the removal of the Madison Avenue Expressway by building a coalition within the community, the City of Youngstown, and the Ohio Department of Transportation. These stakeholders all support the removal of the Madison Avenue Expressway at this location. Eastgate applied for a Reconnecting Communities planning grant to refine the conceptual alternative.

Conceptual planning is underway on the conversion of a 1.5-mile section of Madison Avenue Expressway into a low-speed boulevard with complete streets (bike, pedestrian, transit) facilities integrated into the city’s street grid. The proposed concept would involve reconfiguring the high-speed freeway trench onto the southern frontage road through traffic calming, gateway roundabouts, and a “road diet.” The project would open up over 30 acres of unneeded freeway space to be repurposed as a potential greenspace, university and healthcare campus expansions, and infill mixed-use redevelopment.

Local and regional partners have already mobilized for the Youngstown Equitable & Sustainable (YES) Streets Initiative through a Congressional Directing Spending (CDS) funding request to study integrated transportation, land use, housing, and economic development strategies. The CDS funding request was recommended to the Transportation & Housing and Urban Development Subcommittee for funding by U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH). The YES Streets Initiative will explore opportunities to ensure affordable housing requirements and community benefit agreements are included in the redevelopment of vacated expressway right-of-way and surrounding properties.

Current community members would benefit from removal of a major barrier and enhanced multimodal connectivity between major local institutional assets (Mercy Health - St. Elizabeth Hospital and Youngstown State University); the Downtown Youngstown business, entertainments, and civic districts; Wick Park; and neighboring urban core neighborhoods that have been historically underserved and subject to disinvestment due to the long-term impacts of historic redlining. Neighborhood residents would also enjoy increased greenspace and reductions in freeway noise as a result of the proposed freeway to boulevard conversion.