Freeways Without Futures 2021 tells the story of some of the worst highways in America; the ones that have left a terrible legacy and incredible hurdles for the people who live around them. But it also highlights the resilience of neighborhood residents, local government officials, and activists fighting to remove these blighting highways and reconnect their communities.

The 15 highways featured in this report are prime for a transformation. The people who live around them know that they are problematic. Many are poorly maintained and have become liabilities instead of assets. Straightforward solutions exist to deal with the volume of traffic they carry. Support for changing these highways—to invest in new transportation infrastructure that meets multiple community goals—is widespread.

As debates at the federal level consider infrastructure as a cornerstone for recovery from COVID-19 and Americans are evaluating how to address systematic racism, where do urban highways and their legacy fit? Will we reinvest in and rebuild these structures, continue to support highway expansion, and solidify the physical barriers that separate and destroy? Or can we envision a reparative infrastructure program that reknits communities, addresses the damage these highways have caused, and increases access to opportunities for legacy residents? Media inquiries: Contact Ben Crowther.

- Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, New York, New York

- Claiborne Expressway (I-10), New Orleans, Louisiana

- Inner Loop North, Rochester, New York

- I-244, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- I-275, Tampa, Florida

- I-345, Dallas, Texas

- I-35, Austin, Texas

- I-35, Duluth, Minnesota

- I-5, Seattle, Washington

- I-81, Syracuse, New York

- I-980, Oakland, California

- Kensington Expressway, Buffalo, New York

- North Loop (I-35/70), Kansas City, Missouri

- Scajaquada Expressways, Buffalo, New York

- The Great Highway, San Francisco, California

The current path of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE), at least the portion in Brooklyn Heights, was built out of compromise. To the south, Robert Moses built a tall elevated highway directly through the working-class Red Hook neighborhood, separating it from the rest of the borough. It then cuts a wide trench through Cobble Hill. Moses originally intended the highway to continue straight through Brooklyn Heights, but community protests against this plan prevailed. Instead, the BQE skirted the edge of Brooklyn Heights in its current form as a multi-level cantilevered roadway that forms an effective wall between Brooklyn and its waterfront. The popular Brooklyn Heights promenade was also built as part of this compromise.

Because the Brooklyn Heights section is in dire need of repair and immediate action, planning for the future of this part of the road has received the majority of attention as of late. In particular, a plan to temporarily transform the Brooklyn Heights promenade into a highway while the BQE below it was repaired over several years drew a lot of ire and raised questions about how best to go about rebuilding the road. While that plan was halted through efforts by several area organizations, the developments also sparked conversations about what to do with the remaining ten miles of the BQE that run through some of the densest parts of Brooklyn and Queens.

It is clear that the highway has a detrimental effect on every neighborhood that it passes through, although some are more seriously affected than others. In particular, the wide footprint of the viaducts through the Navy Yard and Greenpoint neighborhoods have facilitated the design of auto-centric streets underneath them that are dangerous for pedestrians to cross. The trenched portion in Cobble Hill can only be crossed at a limited number of access points. And the entire highway subjects thousands of nearby residents to the concentrated exhaust of over 150,000 vehicles per day, many of which are funneled to the BQE to travel the toll-free Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges.

To remedy these issues, a wide variety of organizations have put forward alternate visions for the future of the BQE, some of them limited to particular neighborhoods and others more wide-sweeping. The Cobble Hill Association has called for a cap over the trenched part of the highway in their neighborhood. Marc Wouters Studios’ has proposed a relatively low cost series of public terraces that would extend the promenade over a reduced-width highway. New York’s Institute for Public Architecture focused its Fall 2020 residency on what could be built in place of the BQE if the highway was removed altogether. These are just a handful of the ideas that grapple with the problematic BQE.

While these plans differ in scope and scale, they share a single principle: they all seek to repurpose the space the highway occupies in ways that improve the quality of life for residents along the corridor. As New York City and State consider what to do with the outdated expressway in Brooklyn Heights, they should follow this lead and make sure to prioritize all neighborhoods along the corridor before they develop future plans. The transformation of the BQE offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity to create a more livable Brooklyn and Queens and should be seriously considered.

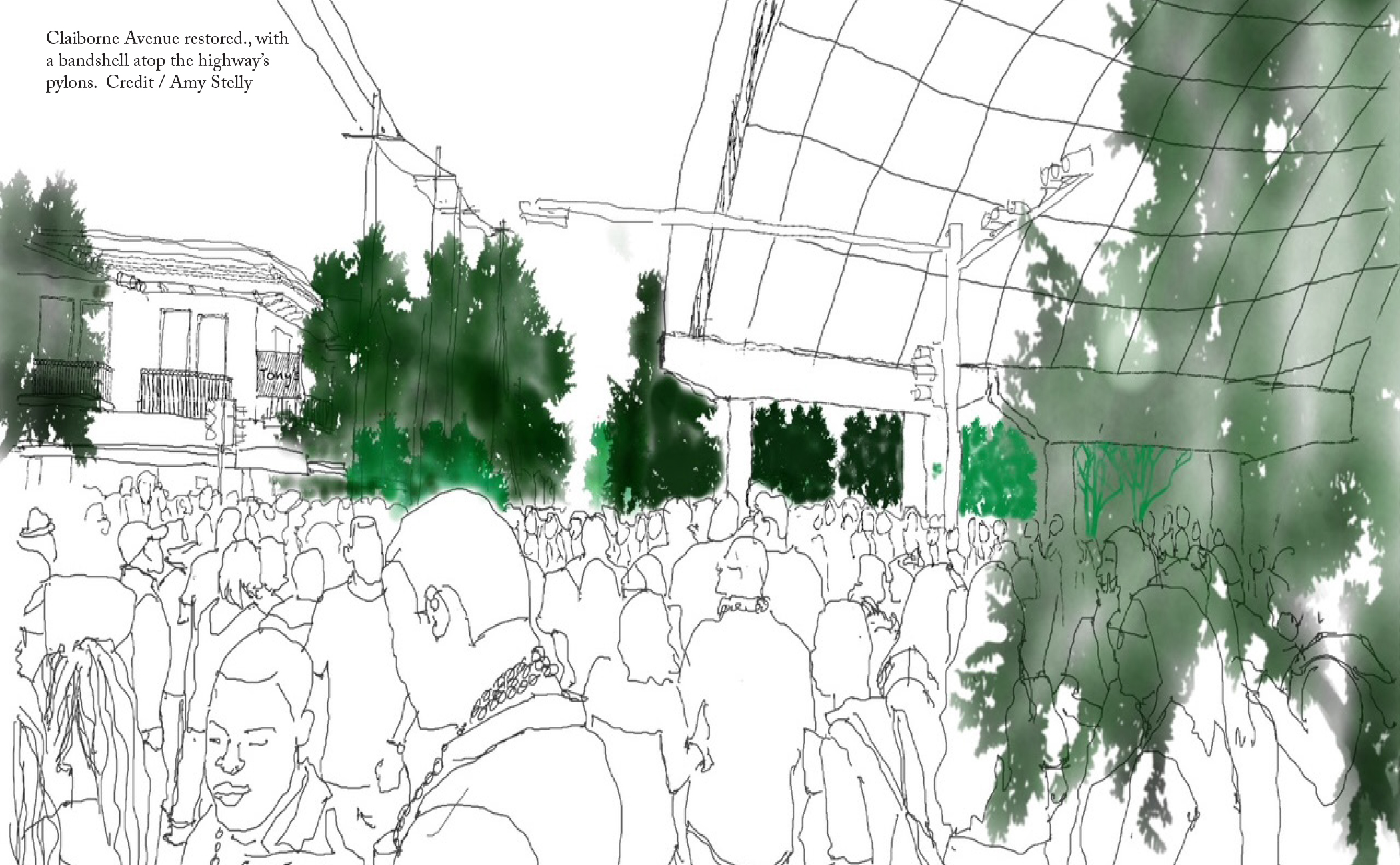

Each year during Mardi Gras, thousands of people wind their way underneath the Claiborne Expressway along what used to be Claiborne Avenue’s median. For these few hours, the grey pavement of the parking lots below the highway is transformed back into a gathering space for the community. Tree-lined Claiborne Avenue wasn’t the only focal point the highway deprived residents of. Dozens of Black-owned shops, restaurants, and clubs shuttered in the years following the highway’s construction.

Fast forward to the present day and those who live and work near the highway are exposed to excessive noise and harmful pollutants. The highway is now crumbling so hot, dirty runoff pours into the neighborhoods during rains, exacerbating flooding. Furthermore, the Louisiana State University School of Public Health confirmed that pollution from the Interstate has a major impact on the respiratory health of residents, making their battle with COVID-19 harder.

Discussions about removing the Claiborne Expressway span back over a decade and since 2017, the Claiborne Avenue Alliance has made great strides championing a community vision for a Claiborne Avenue restored. Previous studies had emphasized the development potential associated with the expressway’s removal, which prompted long-time residents to think this was another infrastructure project that would benefit someone else, again at their expense.

The Alliance’s plans instead seek to channel the benefits unlocked by taking down the expressway to serve the members of the current community. First and foremost, it advocates for the restoration of the median to its former state and restoring the lost tree canopy. This gathering space will serve as the backbone for a revitalized business corridor that brings goods and services back to the neighborhood. There is also the opportunity to create affordable housing through infill development and the rehabilitation of the existing homes that have fallen into disrepair.

All of this is underpinned by policies the city can adopt to protect current residents from being displaced by rising prices once the highway is removed. The early establishment of a community land trust to acquire available real estate and resell it at below market value to residents is a critical strategy to help renters (70% of the community as of the 2010 census) transition to home ownership and stay in the neighborhood. Additional strategies, such as incentive programs that assist residents with home maintenance and tax-freezing programs to relieve the escalating assessments already driven by short-term rentals, will help keep residents in place to enjoy the benefits of a restored Claiborne Avenue.

Currently, the Alliance is building support for this vision. It launched its Paradise Lost|Paradise Found poster campaign in January 2020, which brought public awareness to the damage caused by the Claiborne Expressway and the potential for a brighter future without it. Its work has even received recognition from President Joe Biden, who identified the Claiborne Expressway as a prime example of a highway built at the expense of the community around it. Mayor LaToya Cantrell and incoming U.S. Representative Troy Carter have both expressed support for taking down the expressway and become part of a growing consensus that its removal is the right course of action for Tremé.

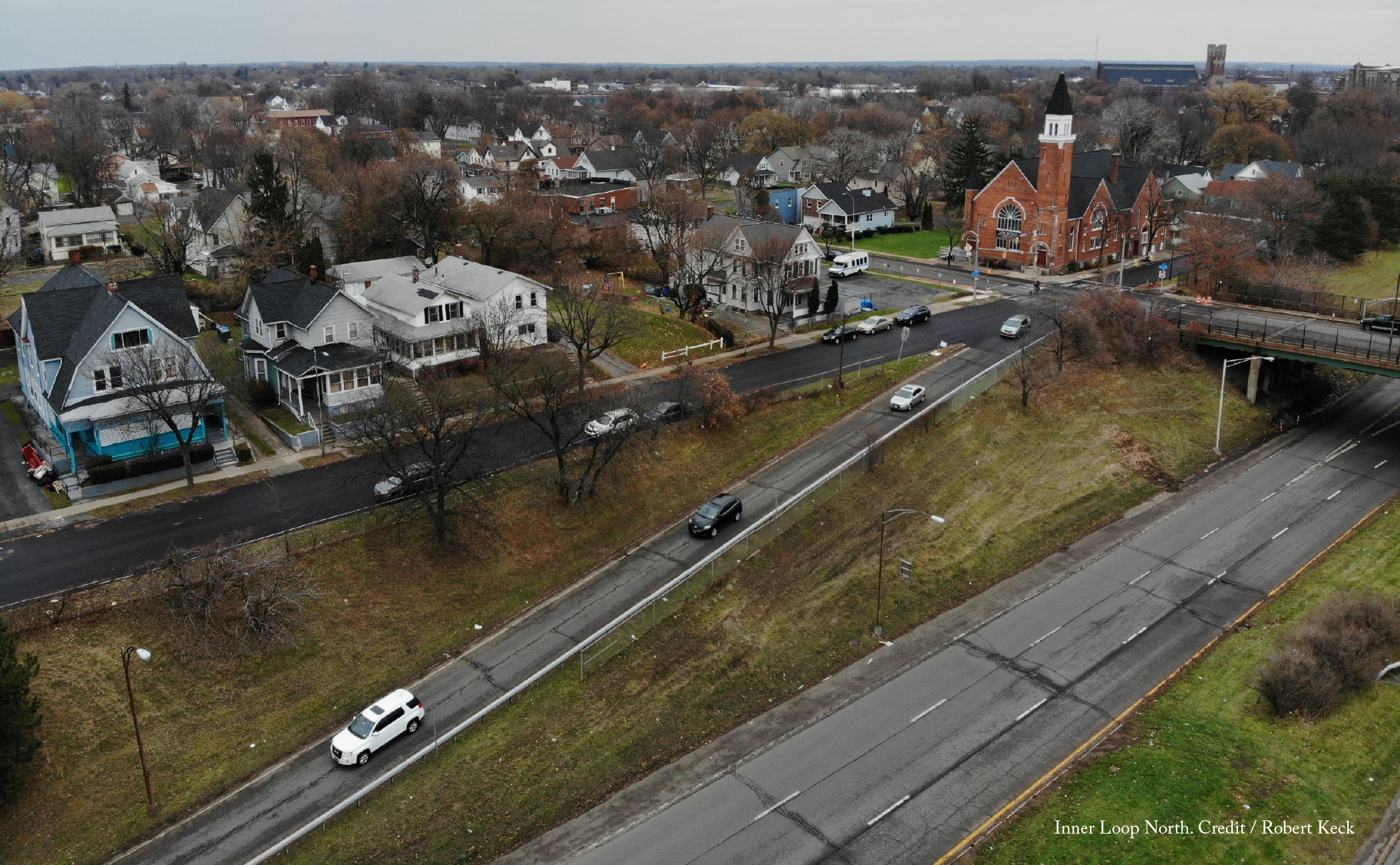

For decades, Rochester’s 2.68-mile Inner Loop acted as a moat between its central business district and adjacent residential neighborhoods. It presented a major barrier to both walking and biking to and from downtown and had become a liability as much of it fell into disrepair and the number of cars traveling on it continued to decline. The Inner Loop East Transformation Project was the City’s first step to address the issues the Inner Loop has caused. The removal of the Inner Loop’s eastern portion was low-hanging fruit, as only 10,500 cars a day drove that part of the highway.

The transformation of the Inner Loop East has served as a demonstration project for highway removal in other parts of the city. Since the project started in 2014, walking increased 50 percent and biking 60 percent in the area. The city was also able to reclaim 6.5 acres of land for development by filling in the highway. The current plan for this land is to develop 534 housing units, more than half subsidized or below market rate, and 152,000 square feet of new commercial space. Work is already underway and over the first two years the removal project, which cost only $22 million in public funds, generated $229 million in economic development.

All this sets the stage for the Inner Loop North. Rochester is now exploring options for removal of this part of the highway, which runs from I-490 to the intersection of Union Street and Main Street. While the City has yet to commit to any specific design for the project, it has laid out a set of guiding principles: it should improve connectivity, increase multi-modal transportation options, create new green spaces, and foster opportunities for economic and community development in surrounding neighborhoods, home to a predominantly Black and brown population. With a focus on racial equity, the project aims to prevent displacement of existing residents and businesses. Preliminary concepts estimate around 15 acres of land could be reclaimed for development, along with several acres of green space.

A group of community members, Hinge Neighbors, is also working with residents on both sides of the Inner Loop to raise awareness about the impacts the project will have and communicate local needs and desires to the City and its consultants. To gather more information, they’ve launched a community survey, which has had some telling results. One of their significant findings is residents’ desire for housing that better fits neighborhood character and different living situations. Four story buildings, full of one- and two-bedroom apartments, don’t address the needs of all community members, even if they include affordable units. Residents would rather see a mix of housing types, including smaller homes that are often described as ‘missing middle’ housing. The City and its partners should take this into serious consideration as they think about creative options for affordability and avoiding displacement following removal.

Rochester’s success with the Inner Loop East garnered national attention. With the removal of the Inner Loop North, the city has the opportunity to once again be at the forefront of the Highways to Boulevards movement. It should lead the way by doing everything in its power to listen to residents and incorporate their ideas into the project’s final designs. At the same time, the City should also explore all the policy tools it can use to support residents and their visions. If Rochester follows through on these commitments, it will be a model for future highway removal projects prioritizing equity.

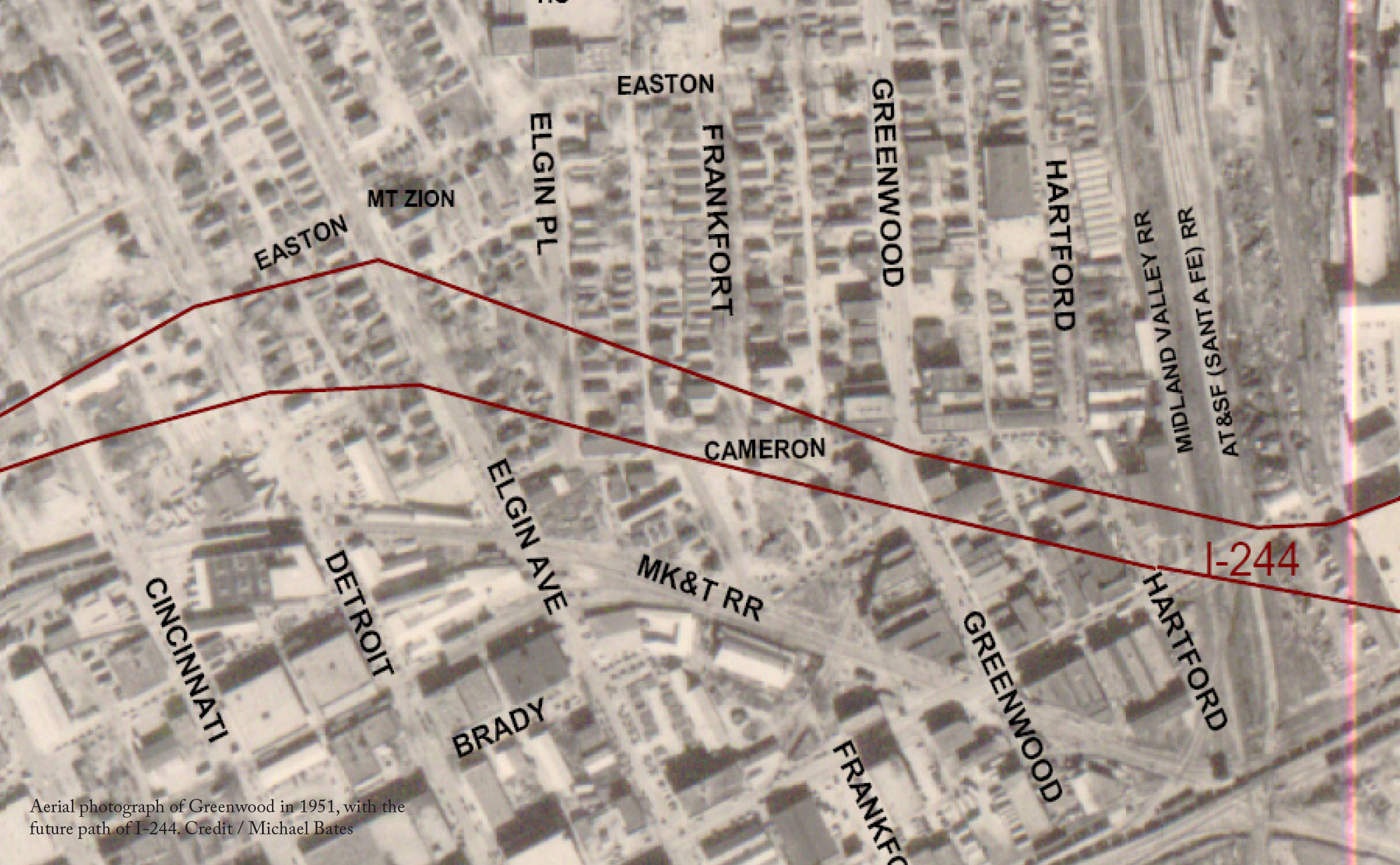

With the end of legal segregation in the early 1960s Greenwood’s businesses had experienced a bit of a decline, as Black spending was no longer concentrated exclusively in the district. But it still remained a source of community pride. I-244’s construction put an abrupt end to any potential revival. The businesses in the highway’s path closed or relocated elsewhere, away from their traditional customer bases. In 1942, Greenwood was home to 242 Black-owned businesses spread over 35 square blocks. The highway reduced that number to only a handful, most situated on the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue, which local attorney E.L. Goodwin, Sr. had saved through negotiations.

Today, I-244 in Greenwood forms the northern part of a series of highways known as the Inner Dispersal Loop (IDL) that cordons off downtown from the rest of Tulsa. Parts of historic Black Wall Street remain in its shadow, including the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue (also known as Deep Greenwood) and a pair of churches (the Mt. Zion Baptist Church and Vernon AME Church) that were burned down during the race massacre but rebuilt afterward. Just north of the highway is the Greenwood Cultural Center, built in 1980 to celebrate the achievements of Black Wall Street residents and remember the tragedy of the race massacre.

These community assets could serve as the foundation for a revitalized Greenwood following the removal of the northern section of I-244 along the IDL. The concept is a nascent one, but the Tulsa Regional Chamber, Historic Greenwood District Main Street, and other local advocates think it is worth exploring. I-244 acts as a physical barrier between predominantly Black north Tulsa and historic Greenwood Avenue and downtown to the south. By removing the highway and restoring street connections, north Tulsans would be able to more easily walk or bike downtown, and business owners in Deep Greenwood would benefit from increased traffic. New land would also be available to expand Deep Greenwood northward, where it is largely constrained by the presence of the highway.

Of course, the removal of I-244 alone won’t restore Black Wall Street. But coordinated reparative programs, coupled with the highway’s removal, can support community efforts to build a new Black Wall Street. This includes programs to help develop new Black-owned businesses and boost existing ones, leveraging the City’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund to create affordable homes within walking distance, and establishing a community land trust to rehabilitate vacant lots and abandoned houses in line with residents’ interests. It will take focused investments and intentional policies like these to rebuild an expanded Greenwood district that does justice to historic Black Wall Street, while also addressing displacement concerns.

This year marks the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre, when Black Wall Street was first destroyed. Now would be a fitting time to carry forward a conversation about I-244’s removal. Preliminary investigation suggests it is more than feasible. This one-mile segment of I-244 is hardly essential for regional travel and Tulsa has a second loop highway, the Gilcrease Expressway, only a few miles to the north. The outstanding question is how to best ensure the highway’s removal and a subsequent restoration of Greenwood helps Black Tulsans heal and thrive.

In many ways, the Florida Department of Transportation’s (FDOT) original $6b expansion plan for I-275 replicated its past transgressions. To widen the road, FDOT needed to seize around 400 properties and of the residents who would have been displaced, nearly 80 percent were Black or Latino. Fifty-four years earlier, FDOT did the same thing when building the highway. The construction of I-275 did incalculable damage to Tampa’s rich ethnic and historic neighborhoods, including Ybor City and Central Park.

Under intense criticism, FDOT backed off its expansion plans and has decided instead to add lanes within the existing right-of-way. But by then Tampa residents had already begun to consider whether the highway’s useful life was coming to an end, particularly as the city looked to update its transportation system for the 21st century.

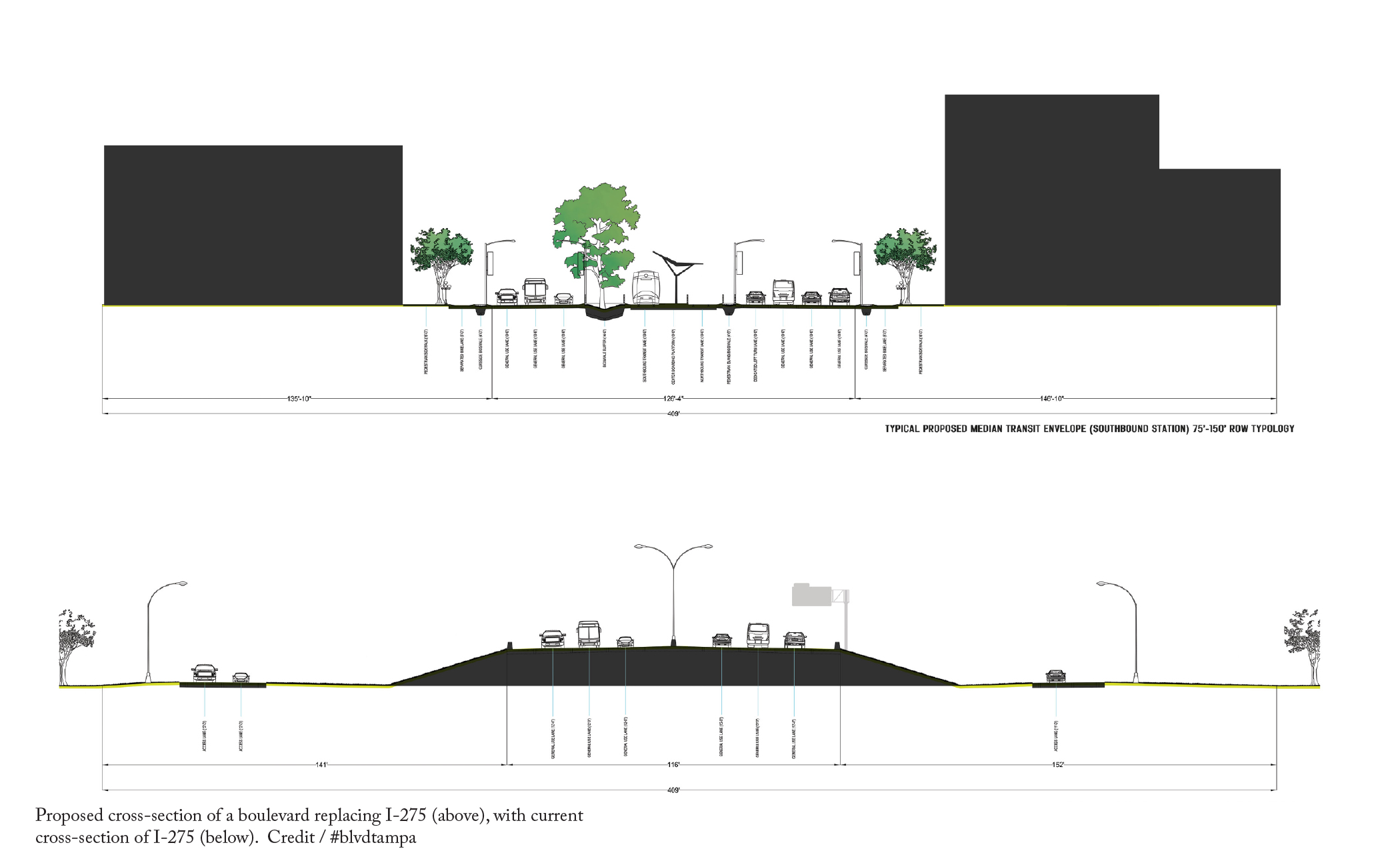

Enter Josh Frank, one of the founders of the #blvdtampa movement, which envisions a future for Tampa without I-275. Frank examined traffic patterns along I-275 and saw that the majority of vehicles that travel it have both local origins and destinations within city limits. Since the Interstate isn’t operating as a throughway (its intended purpose), could another type of street handle traffic and achieve other community goals at the same time?

#blvdtampa and its allies have set out to prove the benefits the city could reap by transforming up to 11 miles of I-275 in northern Tampa into a multiway boulevard, a type of landscaped street that separates through traffic from local traffic and creates an engaging pedestrian realm. Because I-275’s right-of-way is so large, the opportunity exists to fit public transit into its footprint, either in the form of light commuter rail, bus rapid transit, or a modern streetcar, further reducing the need for trips by car.

The transformation of I-275 into a boulevard also prepares Tampa for future sustainable growth. A boulevard along this route provides Tampa a new urban spine that links its residential neighborhoods with downtown. The removal of the highway would reclaim 36 acres of developable land in neighborhoods that are some of the most protected in Tampa from rising sea-levels. With a flexible boulevard design, the new street can be sensitive to local context and change accordingly so that the density built around it gradually increases as it approaches downtown.

The Tampa region is already taking the initial steps needed for the boulevard plan to become reality through incremental endeavors to update its transportation networks. In 2022, Hillsborough County voters expect to vote again on a ballot measure that would fund additional transit routes with faster service, which overwhelmingly passed in 2018 but was struck down by the Florida Supreme Court on a controversial technicality.

Most significantly, in 2019 the Hillsborough County Metropolitan Planning Organization committed to study transforming the highway into a boulevard as part of its long-range plan. What once was seen as a fringe idea has built momentum and spread around Tampa Bay. Neighboring St. Petersburg Mayor Rick Kriseman has said that his city should explore removing I-175, which separates downtown from nearby neighborhoods. In this context, the transformation of I-275 has become as part of a larger effort to improve transportation options across Tampa Bay.

This 1.4-mile stretch of highway forms an imposing concrete barrier that divides the city’s historic Deep Ellum neighborhood from downtown and has spawned vacant lots and disinvestment along its path. Back in 2013, residents Patrick Kennedy and Brandon Hancock recognized the highway had become a liability and together, they founded the group A New Dallas. Since then, the group has demonstrated the social, economic, and environmental benefits for a Dallas without I-345.

It wasn’t long before TxDOT began to take notice and agreed to further investigate what I-345’s removal might mean for Dallas. In 2016, it unveiled the Dallas CityMAP plan, which confirmed that the effects of removing I-345 would be overwhelmingly positive. The removal of the elevated highway would open up 375 acres of urban land for development—with the potential for walkable urban blocks and quality public spaces. The complete removal, a public investment estimated to cost between $100-$500m, would generate at least $2.5b in new property value, supporting both the city’s tax base and a growing economy as the resulting development would also create 39,000 new jobs.

The removal of I-345 can also bring much needed housing to the Dallas market. At the moment, the I-345 corridor is defined primarily by empty parking lots and undeveloped land because the highway is such a disamenity. But its transformation into a mixed-income, mixed-use neighborhood would open up more opportunities to build affordable housing and improve the quality of life for Dallas residents. A New Dallas has since grown into The Coalition for a New Dallas, a non-profit and Political Action Committee composed of a broad and diverse group of advocates and civic leaders. This group has since brought in Toole Design Group to take a fresh look at the CityMAP plan in order to improve design options and demonstrate feasibility.

As plans are put in place for the highway’s removal, The Coalition for a New Dallas thinks that it’s critical for the city to take steps to combat displacement that could result from such a serious improvement. The coalition proposes a variety of value capture and equitable development strategies where the land values are expected to be the highest and diverting some projected revenues to neighborhood stabilization and equitable development programs in areas of need where displacement is a concern. This will help ensure that residents will not only have access to newly built affordable housing, but also that they are able to remain in their current homes if they so desire, ideally with opportunities for renters to build equity.

TxDOT is expected to make a decision about a preferred alternative sometime this year. While other options may mitigate the negative effects of the highway, for The Coalition for a New Dallas there’s only one clear winner: the removal of I-345 and its replacement with a robust newtork of urban boulevards. Dallas is already making investments to transform itself from an auto-centric city to one that is more livable, including the expansion of its subway system that will traverse the I-345 corridor. If TxDOT does its part and removes I-345, this will become a coordinated effort to make Dallas a city where all its residents can enjoy the benefits of jobs and basic services—housing, transit, schools, parks, and retail—available within a short distance.

TxDOT is adamant that there is only one solution for I-35’s woes: a $4.9b highway expansion to up to 20 lanes. This proposal hinges on traffic forecasts that opponents say consistently overestimates actual levels. A growing number of people realize that highway expansion induces even more demand for driving, which quickly fills up the newly-created capacity and leaves congestion as bad or worse. To learn this lesson, TxDOT needs to look no further than Houston, where traffic on the Katy Freeway, expanded up to 26 lanes in 2008, has only gotten worse since it was widened.

So what else can be done for I-35? Local advocacy group Reconnect Austin has long pushed for a solution that keeps I-35 within its current footprint, depresses 3.4 miles of it (from Holly Street to Airport Boulevard), and covers it with a cap. On top of the cap, Reconnect Austin proposes a new boulevard consistent with Austin’s Great Streets Master Plan, which includes generous space for pedestrians, cyclists, and dedicated transit lanes.

Reconnect Austin’s plan has a lot of merit. It separates local traffic from through traffic, eliminating the need for the overly-wide frontage roads that facilitate cars getting on and off the highway. Through the combination of capping the highway, shrinking the street on top of it to a more fitting size, and eliminating frontage roads, Reconnect Austin’s plans reclaim over 130 acres of land for development, of which 24.4 acres would be directly adjacent to downtown. The opportunity to reclaim this land and create an affordable housing supply, immediately adjacent to jobs, would reduce the number of commuters on the road.

Other groups in the area are also thinking about how to change I-35. In 2019, the Urban Land Institute report for the Downtown Austin Alliance proposed caps at several key locations to create blocks-long park spaces, similar to the Klyde Warren Park in Dallas. Another group, Rethink35, proposes removing 8 miles of I-35 altogether and replacing it with a boulevard that includes regional trains, bus lanes, protected bicycle lanes, and wide sidewalks and incorporates anti-displacement measures for nearby communities. Inspired by previous freeway removals, Rethink35 points toward climate change, traffic crashes, automobile dependency, and induced sprawl as to why I-35 should be removed. All three of these coalitions recognize I-35 in its current form as a liability for Austin and seek different ways to create assets along the corridor that provide community benefits.

As TxDOT considers what to do with I-35, it needs to stop thinking about the highway in a vacuum and instead should focus on how its investments can achieve multiple goals simultaneously. Austin’s citizens have made clear their desires for the future of transportation and it is not more highway building. On the 2020 ballot, Austinites voted overwhelmingly to fund Project Connect, a $7.1b initiative to greatly expand the city’s public transit, and to invest $460m in walking, bicycling, and safer streets. Project Connect is also notable in that its budget includes $300 million in anti-displacement funds and so provides a template for keeping residents in place when infrastructure investments increase a neighborhood’s amenities, like a highway cap. With I-35, TxDOT’s should follow Project Connect’s lead and make sure its actions work in concert with Austin’s own plans for its future.

A highway that consumes nearly 20% of all space in Duluth’s downtown, is extremely at odds with the city’s population of 85,618 people. Residents recognized this from the start. After the initial portion of the highway was built through West Duluth and Lincoln Park, residents formed the Citizens for Integration of Highway and Environment in an attempt to steer the highway’s path as it approached downtown. The group ultimately thwarted a plan to build the highway directly along the waterfront, preserving that natural asset, but were unsuccessful in keeping the freeway out of the city’s downtown entirely.

Current conditions make it very appealing to remove the portion of I-35 that runs through downtown, which the Duluth Waterfront Collective advocates for. Traffic on the highway is incredibly light for an Interstate, totaling only 32,000 trips per day. Meanwhile, the Canal Park neighborhood and the preserved green space along the waterfront have become some of the most visited places in Minnesota, yet much of the Duluth community is unable to enjoy it as an amenity. With limited places to cross, the highway limits local travel to and from Canal Park, with the result that few of the park’s visitors make their way into Duluth’s downtown and spend money there. Uphill from downtown is Duluth’s Central Hillside neighborhood, which is one of the city’s most diverse. It has a high number of residents living in poverty, many of whom do not own cars. The presence of I-35 limits their enjoyment of the waterfront as well.

As a replacement for the highway, the Duluth Waterfront Collective envisions a new parkway that condenses I-35 and Railroad Street, but would only increase through travel times by a few minutes. The parkway is planned to be much more accessible to pedestrians and cyclists, with wide sidewalks lined by trees and a new cross-city recreation trail. It’s current iteration calls for dedicated space for bus rapid transit, and includes a rail corridor for the local tourist excursion train and potential future transit options. In the center of the parkway, a landscaped median will provide even more green space in addition to capturing stormwater from the hillside and floodwater from the lake.

The current iteration of the plan also reclaims 20 acres of land from the highway that can be developed in ways that alleviate considerable housing concerns and provide entrepreneurial opportunities for members of the community. It’s a catalytic opportunity to revitalize Duluth’s downtown and help the city fund services for residents by increasing its tax base. The Duluth Waterfront Collective has estimated that the removal of properties to make way for I-35 has cost the city over $3.5 million in lost tax revenue each year since construction started in 1967.

Most importantly, the Duluth Waterfront Collective stresses that its proposed plans are a ‘living concept’, which it updates based upon feedback it receives from the community. The group has taken to conducting the outreach typically undertaken by planning agencies, hosting monthly meetings to discuss the proposal with community members and stakeholders. From this engagement, the Duluth Waterfront Collective will have assembled a community vision for what a great downtown should be, which they can present to the Minnesota Department of Transportation the moment it considers what to do with the highway.

When discussions first began around the construction of I-5, some Seattle residents recognized that the highway would have consequences: notably increased pollution and significantly less street connectivity across the highway. The First Hill Improvement Club was vocal that the highway builders needed to mitigate the road’s effects with lids and other measures. Georgetown residents also sought to preserve the Georgetown Playfield in full. Both of these requests went unanswered. Only in 1976, nine years after the highway was completed, did the City of Seattle step in and support the creation of Freeway Park, a 4.9-acre green space over the highway that at least partially restored lost connections to First Hill. The park became one of the earliest examples in the country of a freeway lid.

Since then, Freeway Park has been expanded several times to encompass a total of 5.2 acres. And it isn’t the only effort that Seattle has undertaken to remove or mitigate the effects of intrusive highways. Interstate 90 in the Mount Baker neighborhood is partially covered by a 10.3-acre lid that supports a regional trail and Sam Smith Park. In 2019 the city removed the Alaskan Way Viaduct that covered its waterfront, opening up this unique natural resource for the enjoyment of its residents.

Since 2015, the advocacy group Lid I-5 has sought to expand on these successes and has worked with the public on new design concepts that could add another 17 acres of lid area over I-5. The group recognizes that an expanded I-5 lid can simultaneously address several of the pressing challenges Seattle faces. Downtown Seattle lacks sufficient green space, and the expansion of the lid could create more for the 40,000 people who would live only a 15-minute walk or less away. The same residents who lack easy access to green space are also concerned about displacement risks, which have increased in downtown since 2010. An expanded lid over I-5 could provide new land on which to build affordable housing in the heart of a diverse neighborhood with both a high displacement risk and high access to opportunity.

Rather than endorsing one particular concept for what gets built on top of the freeway, Lid I-5 remains purposefully flexible so that the greater community can weigh in on plans that can be calibrated to suit local needs. That opportunity is expected to be coming soon. The City of Seattle has taken an interest and recently completed a feasibility study for the project, which demonstrated that lidding more of I-5 is both technically feasible and potentially desirable, as it can significantly improve the quality of life for residents.

Lidding I-5 has the potential to transform downtown Seattle with a win-win opportunity to address equity issues, boost resilience, add green space, and improve public and environmental health. In addition, it can spark important conversations related to other highways across Seattle and how they impact the neighborhoods around them. As the city continues to explore options to cover I-5, it should also look to partner with less well-resourced neighborhoods that are bisected by freeways (like SR 99 in South Park) to develop remedies that lessen or eliminate their negative effects. This larger, coordinated effort could build on Seattle’s past accomplishments and ensure that all the city’s residents benefit from forward-thinking design.

When it was first built over 60 years ago, I-81 valued the convenience and mobility of suburban commuters over the Black and Jewish communities in its path. The construction of this 1.4-mile elevated viaduct forcibly displaced nearly 1,300 15th Ward residents and businesses and left a legacy of disinvestment in its wake. What had formerly been one of the densest parts of the city was transformed into acres of abandoned property. Many Black residents, even if they had the means to move, were unable to because of redlining and had little option but to live around the declining conditions of the new highway. These effects are still felt today and contribute to wealth disparities across the Central New York region.

The removal of I-81 viaduct through the city center, the physical manifestation of the policies perpetuating inequality, has the power to change this status quo and heal Syracuse’s 60-year divide. For this reason, the Community Grid alternative gained widespread support when NYSDOT began to consider what to do with the crumbling I-81 over a decade ago. With the backing of dozens of community groups, Syracuse Mayor Ben Walsh, and even Governor Andrew Cuomo, the Community Grid was selected by NYSDOT in April 2019 as its preferred alternative when it released its preliminary Draft Environmental Impact Statement. President Joe Biden has added his endorsement, calling out I-81 as a transportation investment that has divided communities.

In its current form, NYSDOT’s Community Grid alternative removes the elevated viaduct and replaces it with restored city streets, with Almond Street becoming the principal thoroughfare. Through-traffic would be rerouted around the city using the existing I-481 bypass, which would be redesignated as I-81. Under this plan, NYSDOT calculates that travel times into the city as well as around it would change by no more than a few minutes, if at all.

While NYSDOT should be applauded for taking this momentous first step toward removing the highway, there is still much to be done. NYSDOT’s plans don’t take into account the project’s ramifications other than its traffic impacts. In particular, it says little about the effects it will have on the residents who live around it. While residents prefer to see the highway come down, they are skeptical that they’ll receive any of the benefits of removal and fear instead that they will be priced out of the neighborhood as removal gets underway. To ensure more equitable outcomes, the New York Civil Liberties Union has worked with members of the community to create recommendations NYSDOT should adopt, including the creation of a community land trust to steer the development of land reclaimed from the highway. This is just one of the ways that NYSDOT can be more intentional about empowering the community’s vision for the corridor after the highway.

It is likely that I-81 will be the first of all the highways featured in this edition of the report to be removed. It has the potential to herald a new generation of Highways to Boulevards projects, ones that seek to right historical wrongs and remedy spatial injustices. NYSDOT has the power to make the removal of I-81 through the center of Syracuse a reparative infrastructure investment that centers the residents who have lived with the burden of the highway. It only needs to follow through.

Construction on I-980 had started in 1962 but had stalled out several times in the face of lawsuits that cited significant environmental and housing concerns. A portion of the right-of-way had already been cleared, leaving a no man’s land separating parts of West Oakland from the rest of the city. Finally, in 1977, the City of Oakland decided I-980 was crucial to its economic development efforts and the residents of primarily-Black West Oakland realized they had leverage. The partially constructed freeway was already a barrier, so why not get something in exchange for letting the City proceed with its plans? In the end, residents secured new housing and rent protections from the city and some of their houses in the highway’s path were even relocated.

Thirty-five years later, the residents of West Oakland now have leverage again, as I-980 approaches the end of its designed lifespan and the city decides whether or not to dismantle the highway. There are many potential advantages to removal. The highway inhibits West Oakland residents from easily accessing downtown on foot and by bike, with a daunting route that consists not only of the Interstate, but also a pair of frontage roads that serve fast-moving traffic. Furthermore, the highway is largely underutilized, carrying only 53 percent of its potential capacity, mostly local traffic with both origins and destinations along the northern part of the corridor.

Advocacy group ConnectOakland has developed a vision for removal that addresses both these local as well as regional mobility needs, in addition to other community goals. Designs remain flexible to achieve the best solution possible for the residents who live along the I-980 corridor but crucial components include: the replacement of the highway with a roughly 75 percent narrower street, the reconnection of at least 13 cross streets severed by the highway, the potential to incorporate regional transit (including a new BART line) into the current right-of-way, and the reclamation of around 17 acres of land for new development.

Housing also comes to the fore in these discussions. The land reclaimed from the highway could be developed for any type, use, or intensity that will best serve West Oakland’s residents, including affordable housing and community services that prevent displacement. ConnectOakland thinks removal is worthwhile only if the city and other agencies that oversee it cede much of the design and planning process to community members, so that it’s their vision for the neighborhood without the highway that gets built.

The City of Oakland is actively exploring the removal of I-980 as part of its soon to be adopted Downtown Oakland Specific Plan and is starting to bring together community leaders and government stakeholders in roundtable discussions about I-980’s future.

“Building from the success of Mandela Parkway – the result of the Cypress Freeway’s removal – we recognize that West Oakland residents must guide government leaders in their vision for healing from this scar,” says Warren Logan, the City’s Policy Director of Mobility and Interagency Relations, “The time is ripe for this conversation as the region plans for a second Bay Area rail crossing and federal leadership has signaled interest in supporting these types of restorative projects. We know that West Oaklanders represent the best of our City — they are resilient, creative, and tenacious – and are up for the task!”

In 1950, Buffalo was the 15th largest city in the United States and Hamlin Park, the neighborhood that would be targeted by the future Kensington Expressway, was considered one of its most stable neighborhoods. Decades earlier, it had been developed specifically as an inner-city suburb, with tree-lined streets marketed to upwardly mobile, middle-class German immigrants.

But in the 1950s, a combination of events reshaped the neighborhood. Black professionals and their families, seeking the same middle-class quality of life, started purchasing homes in Hamlin Park. Real estate agents, preying on racially-charged fears, ushered in an era of white flight and drained Hamlin Park of the political capital needed to fight the highway. In the end, the expressway deprived the Black Hamlin Park residents of the benefits of Olmsted’s Humboldt Parkway, instead leaving in its place a legacy of vehicle pollution, homes with depreciated value, and severed connections from other parts of the city.

In 2014, a group of Hamlin Park residents, the Restore Our Community Coalition (ROCC), launched its “I Remember” public awareness campaign. It combines historical archives, testimonies from past and present residents, and case studies from comparable projects in other cities to build a community-focused narrative for restoring a third of the original Humboldt Parkway. As a solution, ROCC proposes a green cover over approximately one linear mile, or 14 acres of the expressway’s imprint, from East Ferry Street to Best Street.

While some community members would like to see the expressway removed entirely, others are concerned that the NYSDOT would build a surface-level road with highway-like qualities as a replacement. As an alternative, they have rallied around the idea of a cap, which would still reap substantial benefits for the community. The 2014 Humboldt Parkway Deck Economic Impact Study projects that the restoration of the parkway will bring significant reinvestment to the Jefferson and Fillmore business districts that bookend Hamlin Park. In turn, this could generate up to $2.8m in new property tax revenue for the City of Buffalo over a 30-year period, in addition to $76.7m in household wealth.

In 2016, Governor Andrew Cuomo backed a $6m environmental impact study of different capping options for the expressway. But when NYSDOT unveiled the options in 2019, they were underwhelming at best, providing only limited connections across the highway and failing to reduce air or noise pollution. The presented alternatives were far from a parkway restoration. Renderings showed few street trees and placed an exaggerated ventilation facility at the end of the cap that resembles a factory with smokestacks. Critics suspect this was an intentional ‘poison pill’, designed by NYSDOT to make the Humboldt cap seem unappealing.

NYSDOT must either return to the drawing board or turn the process over to someone who is willing to cooperate with immediate stakeholders, like with Buffalo’s Scajaquada Expressway when it was unable to finalize a solution the larger community could support. The Kensington Expressway has contributed to Buffalo’s economic decline over the past 70 years. As Buffalo continues to overcome past mistakes, it needs a solution for this highway that will bring long-term investments to the Hamlin Park community.

Many of Kansas City’s neighborhoods are effectively islands, divided by seas of asphalt and concrete. Nowhere is this more true than Kansas City’s Central Business District, which is penned in on all four sides by Interstate highways. The north side of this loop is particularly invasive, a tangle of ramps, interchanges, and highways that separate three neighborhoods: the Central Business District, River Market, and Columbus Park, from each other. Prior to the highways, Independence Avenue seamlessly linked all three neighborhoods.

Traffic studies undertaken as part of the Buck O’Neil Bridge rebuilding suggest that the removal of the North Loop, the redesign of Route 9 as a city street, and the reconnection of Independence Avenue between Columbus Park and River Market were all feasible without noticeably increasing travel times. This raises a significant question: if expensive highway infrastructure wasn’t necessary to serve Kansas City’s transportation needs, what else could be built in its place?

Beyond the Loop, a collaboration between the Mid-America Regional Council, the City of Kansas City, and the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT), proposes several visions for the north side of downtown without the highway. It explores a range of options, from keeping the current highway to shrinking its footprint to removal and replacement with a restored Independence Avenue. Unsurprisingly, the removal option scored highest among all options in the categories of physical conditions, improved transportation choices, and improved economic vitality and placemaking, while only causing a slight increase in traffic.

Beyond the Loop also recommends other parallel projects that would go hand-in-hand with a North Loop removal and amplify its effects. Key among them is the removal of the elevated Route 9 and its replacement with an at-grade street. Once the Buck O’Neil Bridge is replaced, MoDOT projects Route 9 will only carry around 12,000 cars per day, which is less traffic than MoDOT estimates for many of downtown’s existing two lane streets. Rebuilding Route 9 as a street without highway-like qualities will not only restore connections between River Market and Columbus Park, but also remove the oversized cloverleaf interchange that connects it to the North Loop. Roughly five city blocks could be created from the land the interchange now occupies, an opportunity for incremental improvement before a possible North Loop removal.

An Urban Land Institute panel on the North Loop removal indicates that market conditions would be prime starting in 2028, so Kansas City should begin planning now. One high priority should be to establish strategies to combat displacement once investments are made. Kansas City already has an incentive program for formerly redlined neighborhoods that offers a 10-year tax abatement when owners spend at least $5,000 per unit on renovations. The city can build on this program and develop an exterior grant program for those who can’t afford to make improvements, as well as create large-scale incentives for affordable rental housing built on the highway’s right-of-way. That way the City and its residents will be ready for when it becomes time to transform the North Loop.

The centerpiece of Buffalo’s parks system designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in the late 1800s, Delaware Park today remains a favorite recreation spot for Buffalonians.Given the park’s sustained popularity, the construction of the high-speed Scajaquada Expressway through it in 1962 might come as a surprise to many. But the City of Buffalo Planning Commission that initiated the project justified the route because it viewed the park as ‘vacant land,’ not a community asset.

Unsurprisingly, the construction of the expressway had negative consequences for the park and those who lived around it. It divided and destroyed acres of parkland, cut off residential sectors from the park and waterfront, and obliterated the Humboldt Parkway, not to mention bisecting established neighborhoods east and west of the park. Speeding vehicles have also made parts of the park unsafe. In 2015, a driver veered off the road and killed a three-year old boy walking in the park with his family. Governor Andrew Cuomo was quick to respond, reducing the posted speed limit from 50 mph to 30 mph. But this has done little to slow cars, as the number of speeding tickets issued on the road in 2019 approached 2015 levels.

The most effective way to curtail dangerous driving is to redesign the road in ways that calm traffic. For the Scajaquada Expressway, this was recognized as early as 2005, when the city and state presented a project proposal to replace the expressway with a parkway designed for 30 mph travel that included safe pedestrian access, dedicated bicycle facilities, and a tree-lined median. After the 2015 fatal crash, thirteen local organizations, including the Buffalo Olmsted Park Conservancy, the Restore of Community Coalition, and GObike Buffalo, joined forces to form the Scajaquada Corridor Coalition to renew the call for a parkway that fits the context of Delaware Park and its adjacent neighborhoods.

At the governor’s direction, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) took charge of executing these changes, but added an additional project goal at odds with the rest: the maintenance of the existing level of service for vehicles. So when NYSDOT revealed its solutions in 2017, its designs for the proposed parkway had morphed into another high-speed, four-lane roadway similar to the existing expressway. After intense community pressure, NYSDOT walked away from the project in January 2018 and turned the planning process over to the Greater Buffalo Niagara Regional Transportation Council (GBNRTC) in 2019.

Community stakeholders have been vocal that the removal of the Scajaquada Expressway goes beyond getting rid of a dangerous roadway; rather it is a step toward realizing Buffalo’s future potential and increasing its residents’ quality of life. Numerous regional assets are located along the corridor and currently separated by the highway, including many of Western New York’s key cultural and educational institutions and the suppressed Scajaquada Creek. As the GBNRTC resumes its work after the COVID-19 pandemic, it should focus on restoring the legacy of a park and parkways system that connects Buffalo’s vibrant communities, treasured historic landscape, and healthy waterways along a corridor where all modes of transportation are safe, accessible, and welcoming.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, people began to reconsider their relationship to transportation. With non-essential businesses closed and stay-at-home orders in place, traffic levels plummeted overnight. But even prior to the pandemic, San Francisco’s Great Highway was already closed. The 3.5 mile-long commuter road sits adjacent to the dunes along the Pacific coast and every time it’s overwhelmed by sand or erosion, it is forced to close -- sometimes for as much as 30% of the year. So when the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) started identifying potential car-free streets to enable social distancing, the Great Highway became an obvious choice.

As a pedestrian-only space, the Great Highway has achieved notable success. SFMTA collected data on the street’s usage from September-November 2020 (i.e. the offseason) and found an average of 6,800 bicyclists and pedestrians per weekend day. In essence, the street has become a flexible public space where some people still use it for transportation (albeit on bicycle), others recreate, and it has even served as a site of Black Lives Matter rallies and a march against Asian American and Pacific Islander hate.

All this has led to a debate about the Great Highway’s future. Given its popularity without cars, should it stay that way permanently? The members of the Great Highway Park Initiative think so. The group has started working with community members and the relevant San Francisco agencies to outline a plan to keep the street pedestrian-only. They’ve identified four key pillars that will make this possible: reduce traffic, safer streets, improve the park, and inclusive access.

One of the key components of their plan is to reduce the number of cars driving through the Sunset district by introducing traffic calming measures. There are other north-south routes built for commuting, but drivers opt to travel through the neighborhood because there are few controls on speed. For instance, on the Lower Great Highway (the street parallel to the Great Highway), seven out of fifteen intersections had no north-south stop signs at the outset of the closure. Since then, dozens of speed bumps, stop signs, and other traffic calming measures have been added to help keep neighborhood streets safe.

The Great Highway Park Initiative also advocates for a few simple and inexpensive changes that would vastly improve the Great Highway as a park/bikeway. The addition of basic amenities, such as water fountains, trash and recycling bins, and places to safely lock bicycles could drastically improve the usability of the park. Access to the park also needs to be inclusive, regardless of how people are able to get there. The initiative wants the city to increase transportation options so everyone can enjoy the park, but also recognizes that, for some, it will only be accessible by car and parking needs to be considered for both visitors and current residents.

Because of the park’s popularity, the SFMTA has initiated a study to explore the long-term future of the Great Highway and wants to ground it in deep community engagement. Once completed, the city could act quickly as the City’s Recreation and Parks department already owns the street and its right-of-way, even if it falls under the jurisdiction of several different agencies. Meanwhile, thousands of visitors each day will continue to enjoy the Great Highway as a park and demonstrate the need for this unique community space.