Freeways Without Futures 2019 is the tale of ten freeways in cities coast to coast where this movement has spawned active campaigns for transformation. Here are the fundamental questions that these campaigns raise: Do we continue to funnel billions of taxpayer dollars into an aging system that pollutes cities, divides neighborhoods, and occupies valuable land that could instead be used for homes and businesses? Or is there an alternative solution that creates stronger cities and communities?

As cities consider what to do with their aging in-city highways, they should recognize the opportunities for freeway removal and transformation. As the ten projects in this report demonstrate, cities can save money while boosting their economies and improving the lives of citizens by not repeating the mistakes of the 20th Century. Media inquiries: Contact Ben Crowther.

- Claiborne Expressway (I-10), New Orleans, Louisiana

- I-275, Tampa, Florida

- I-345, Dallas, Texas

- I-35, Austin, Texas

- I-5, Portland, Oregon

- I-64, Louisville, Kentucky

- I-70, Denver, Colorado

- I-81, Syracuse, New York

- I-980, Oakland, California

- Kensington and Scajaquada Expressways, Buffalo, New York

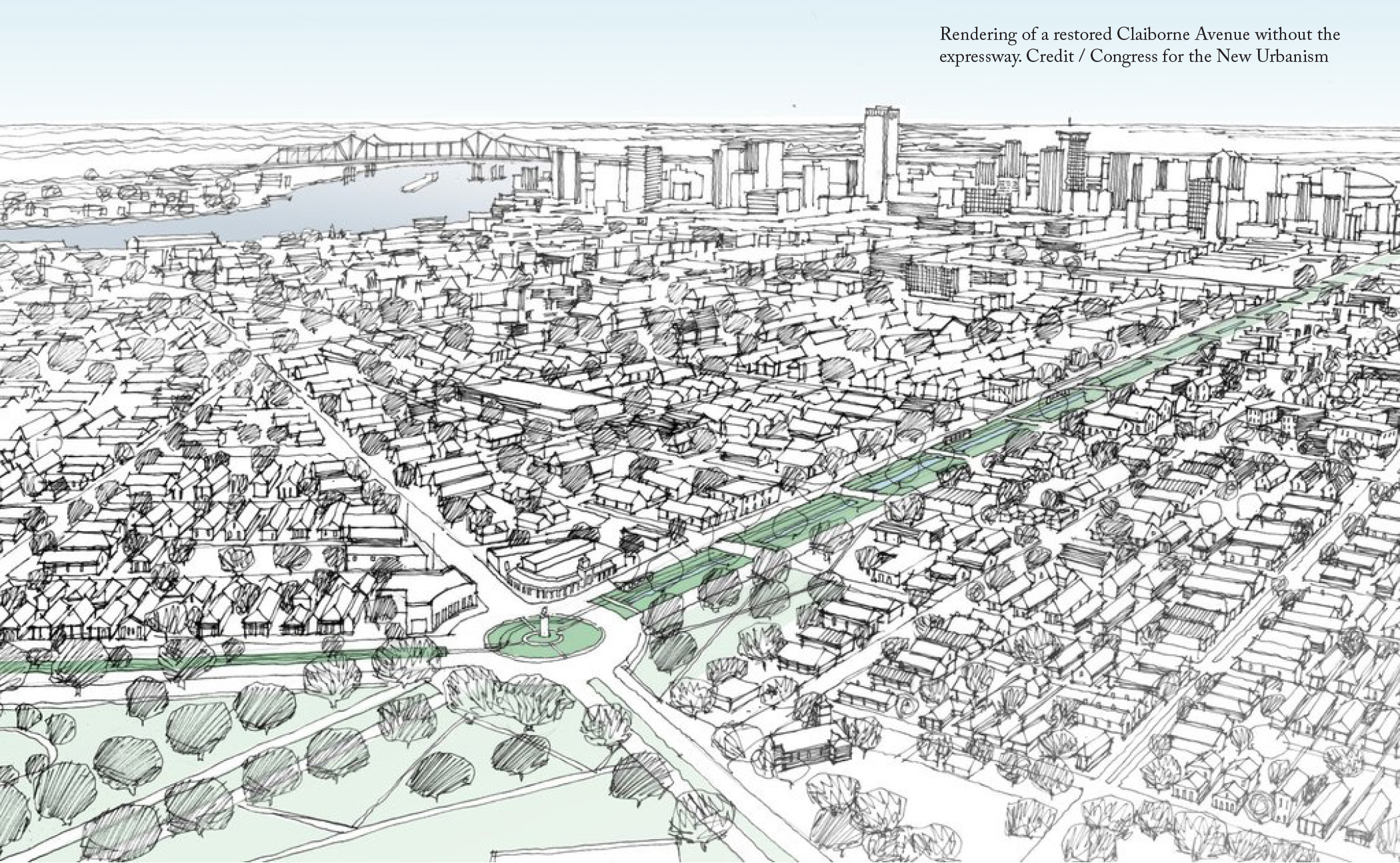

Today, Claiborne Avenue has been reduced to a frontage road for the expressway, but it had a significantly different character prior to 1966. Its wide, green median was the central public space for the African-American neighborhood and a gathering place for the community, with activities that ranged from pickup ball games to Mardi Gras parades. Claiborne Avenue was a source of community pride and the premier destination for shopping, leisure, and socializing. However, when plans for the Claiborne Expressway were revealed, the Tremé community did not have advocates in the city government to defend it.

Many community members whose friends and families opposed the original construction of the Claiborne Expressway still seek to return Claiborne Avenue to the vibrant street it once was. This includes removing the elevated expressway to restore the 100-foot median, the traffic circle at the intersection with St. Bernard Avenue, and connections to the neighborhood’s street grid. Deliberations have long centered on the expressway’s removal, and studies have demonstrated that the effect on New Orleans’ local traffic would be negligible, while through-traffic would experience an increase in travel time of only two to six minutes. In 2014, then-Mayor Mitch Landrieu explored removal as an option, but eventually backed away from this alternative. Discussions stalled. The mayor then proposed building a marketplace underneath the polluting highway, which received a less-than-enthusiastic reception from neighborhood residents.

Since 2017, the Claiborne Avenue Alliance—a coalition of residents, property owners, and business leaders dedicated to the thoughtful development of the Claiborne corridor—has led a renewed effort to remove the expressway and rebuild the avenue. The group has set about to document the negative effects the freeway has on adjacent neighborhoods, from severe pollution to the creation of a food desert. The group has also emphasized the positive potential outcomes of removing the freeway. A restored Claiborne Avenue would attract new businesses and jobs to this once-vibrant commercial corridor, as many of the vacant lots adjacent to the highway become redeveloped. All told, nearly 50 acres of land would be reclaimed from the highway’s shadow. The Claiborne Avenue Alliance advocates that the city devote a large portion of this reclaimed land to the creation of affordable housing and commercial spaces. This would address significant community concerns: While many Tremé residents want to see Claiborne Avenue restored, they fear that such an improvement could price them out of the neighborhood.

Political traction for the expressway’s removal is again on the rise. Recently, Mayor LaToya Cantrell sent her staff to tour the former site of the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco, one of the first elevated freeways in the United States to be converted into a boulevard. City Council president Jason Williams also joined them.

Longtime Tremé residents have made sure to perpetuate conversations around the highway’s removal and the restoration of Claiborne Avenue. Their persistence stems from memories of a great avenue, once an economic and cultural asset for the community, and a vision for the future that provides a similar place for generations to come.

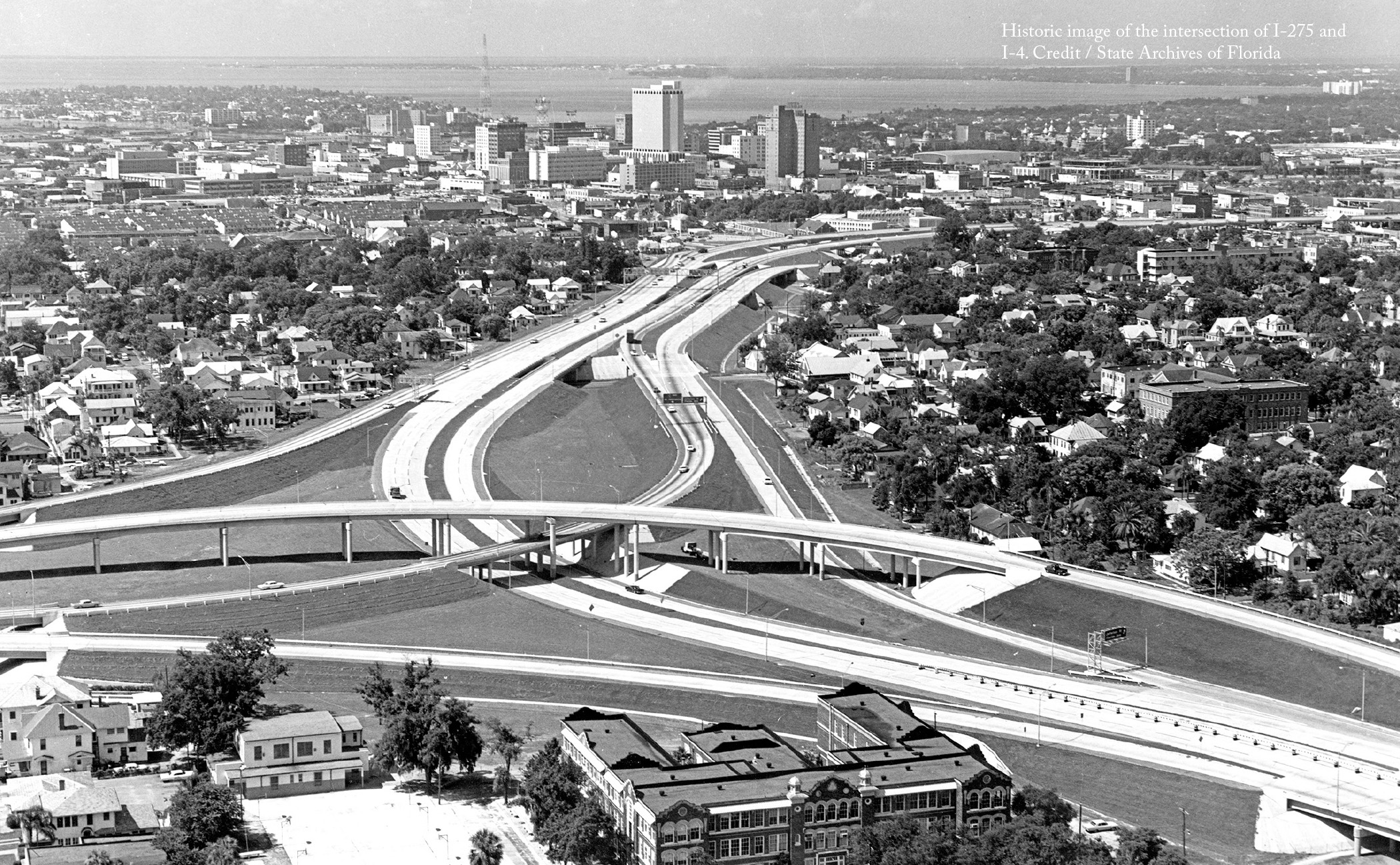

I-275 was built on top of Tampa’s former Central Avenue and split the entire city in half. Incalculable damage was done to Tampa’s rich ethnic and historic neighborhoods, including Ybor City, the former cigar manufacturing capital of the world; and Central Park, the African-American neighborhood that some called the “Harlem of the South”—a one-time home to Ray Charles and often visited by top musicians of the era like Chubby Checker and Ella Fitzgerald.

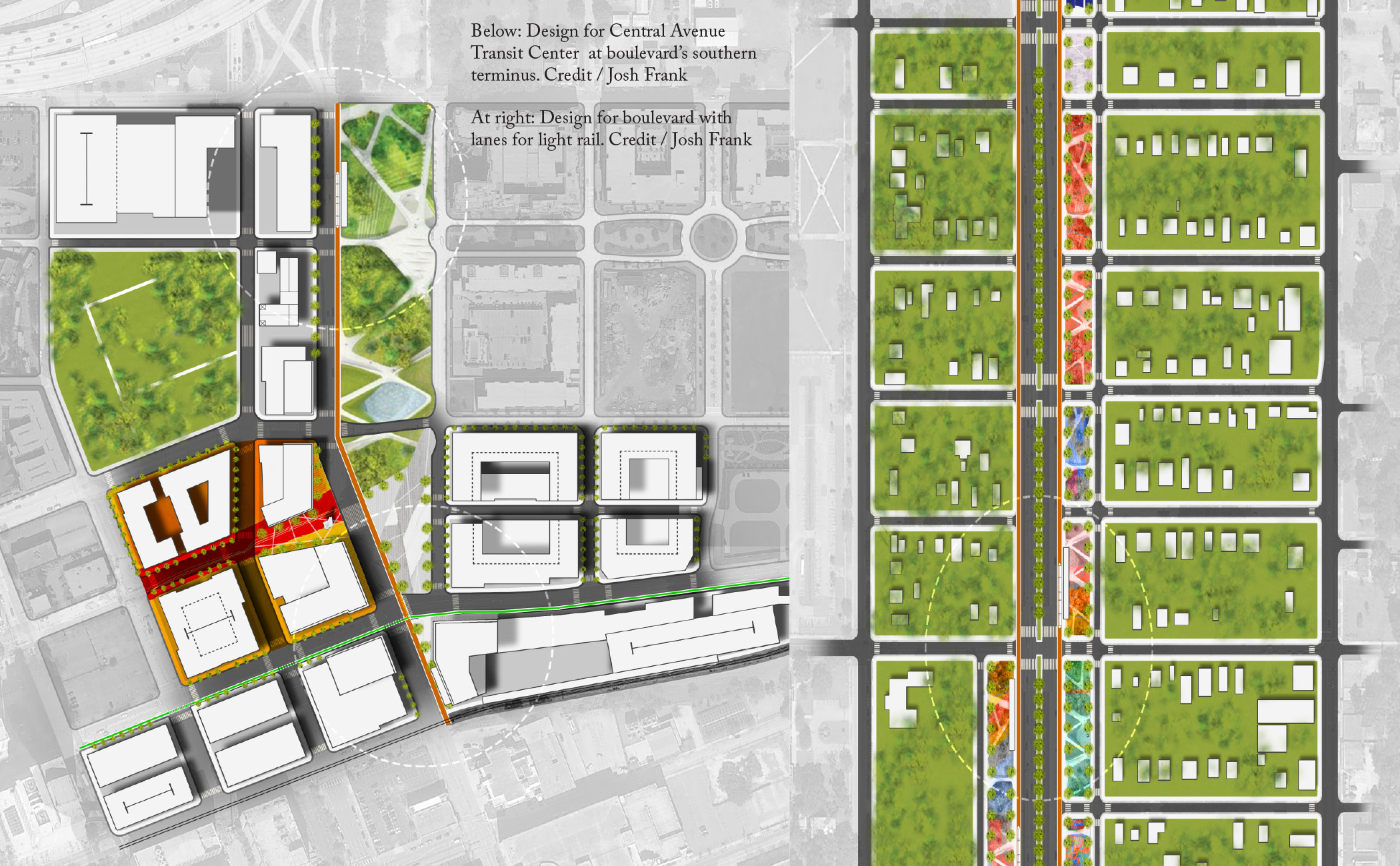

Recent proposals by the FDOT to reconstruct the aging freeway with an expanded footprint and variable toll lanes have catalyzed community opposition to the project. One concerned citizen, Josh Frank, has started a movement, #blvdtampa, that envisions a future for Tampa without I-275.

Armed with extensive traffic data, Frank has demonstrated that Tampa is ill-served by a limited-access highway—as the majority of vehicles that travel I-275 have both local origins and destinations within the city. Instead of rebuilding the highway, #blvdtampa proposes replacing it with a boulevard more suited to local traffic.

The transformation of I-275 into a wide, landscaped boulevard, featuring bike and pedestrian paths and either light commuter rail, bus rapid transit, or a modern streetcar would give Tampa an urban spine around which to grow. The boulevard could include slow-moving local lanes protected from the main traffic, on-street parking, cycling access, pedestrian refuges that reduce crossing distances, and bus shelters.

The economic benefits of this proposal are substantial. Estimates to rebuild the highway range from $3-9 billion, much of which could be saved with the boulevard option. The removal of the oversized highway would immediately open up more than 35 acres for development, boosting the City’s tax base. Coupled with investment in public transit along the corridor, depressed property values in the neighborhoods around the highway would be expected to rise.

Moreover, the boulevard option has the potential to significantly improve the quality of life for people who live nearby. Thousands of homes lie within 1,000 feet of the highway, where air pollutants are most concentrated. Increased transit service on the boulevard would remove polluting vehicles from the road and offer alternatives to driving for residents who currently have few other options.

Although the proposed 11-mile removal of I-275 is ambitious, local organizations such as Sunshine Citizens, Heights Urban Core Chamber, and the Tampa Heights Neighborhood Association, as well as several members of the Hillsborough County commission and candidates for Mayor of Tampa, support transformation of the highway. The strong community support for the #blvdtampa proposal has led the Hillsborough Metropolitan Planning Organization,Tampa’s regional planning agency, to include it as an option in its long-range transportation plan. Currently the campaign has begun to advocate its plan at the state level, as organizers have met twice with local District 7 FDOT officials, who now recognize the multi-modal transit corridor as an alternative option.

I-345 in Dallas is nearing the end of its lifespan. When it was built more than 40 years ago, I-345 separated the predominantly African-American Deep Ellum neighborhood from downtown. In its mid-20th Century heyday, Deep Ellum was a mecca of jazz and blues in the Southwest, and was one of first commercial districts in the city for African-Americans and European immigrants. The construction of I-345 obliterated the 2400 block of Elm Street, which had been the heart of the neighborhood. By the end of the 1970s, few of the community’s original businesses survived. While Deep Ellum now enjoys new life as a music and arts district, the presence of I-345 still inhibits its full integration into the city.

Residents Patrick Kennedy and Brandon Hancock view the deteriorated state of I-345 as an opportunity to consider alternatives to the highway. Together, they founded A New Dallas to advocate for creating a better city through the removal of I-345. The organization has commissioned studies that demonstrate the social, economic, and environmental benefits for a Dallas without the highway. When TxDOT released its CityMAP assessment of Dallas’ urban highways, it included two options for I-345’s transformation: One replaces the elevated highway with a tunnel and surface boulevard, the other with only a surface boulevard.

A New Dallas deems the tunnel an unnecessary expense, as the existing street network adjacent to the highway has a capacity of 178,000 cars a day, far exceeding the current traffic of 105,000 cars a day. The group estimates that burying the highway would cost between $900 million and $1.2 billion, while replacing it with a boulevard will cost only approximately $65 million.

The economic benefits of removal also surpass those of burial. The removal of the elevated highway will open up 245 acres of urban land for potential development—envisioned as walkable urban blocks, with squares and neighborhood public spaces within a short distance of each building. According to TxDOT’s CityMAP study, the complete removal would generate $2.5 billion in new property value, while the burial would generate $1 billion less, as it still requires more than 30 acres of the public right-of-way. Similarly, the city would receive $80 million each year in tax revenue with complete removal, but only $50 million with the below-grade modification. This extra revenue could be leveraged to boost housing affordability and quality of life along the I-345 corridor. Moreover, the land reclaimed from the highway’s right-of-way will return to the city, putting the public in the driver’s seat of planning and implementation for redevelopment.

These powerful economic arguments have made it possible for A New Dallas to build a coalition of community members, urban planners, developers, and civic leaders from across the political spectrum in support of full removal of I-345. The common threads among all these supporters are that they value metrics and consider a broad range of criteria in determining the success of public infrastructure. As Dallas continues to experience rapid urban growth and increased demand for housing, the removal of I-345 offers one way forward to keep the city livable.

The I-35 corridor redesign proposed by Reconnect Austin seeks to take TxDOT’s implementation of depressed freeway lanes in Austin one step further. Reconnect Austin endorses a four-step plan to restore the city’s urban grid and reunify East and West Austin: (1) Remove the elevated highway between Cesar Chavez Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard; (2) Remove existing highway frontage roads to reclaim 30 acres of downtown land; (3) Bury this section of I-35 below ground; and (4) Cover these depressed lanes with a new, narrower, pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly boulevard.

Reconnect Austin envisions a new boulevard that recaptures the dynamic urban space of the former East Avenue the highway replaced. Its design for a new East Avenue Parkway would be consistent with Austin’s Great Streets Master Plan and include more-than-adequate space for pedestrians, cyclists, and dedicated transit lanes. The reconnected grid would create as many as 11 cross streets, “providing better traffic dispersion and more connections for cycling and walking.” The narrower right-of-way with new buildings to define it and the large median in the middle of the street would make pedestrian travel between East and West Austin far easier and more pleasant.

By capping I-35, the 30 acres of land currently under its frontage roads could be opened up for mixed-use development as part of a tax increment financing (TIF) district. The potential valuation from this land is an estimated $10 billion, which would increase the tax base for local jurisdictions by millions of dollars. If handled with care, this could lead to the creation of up to 4,500 market-rate and affordable housing units in a walkable location, ideal for people seeking or currently holding low- and moderate-income jobs downtown.

Reconnect Austin acknowledges that the removal of I-35 also has the potential to accelerate gentrification and displacement, as the area becomes more economically robust and aesthetically attractive, potentially leading to soaring land values. Having a plan in place to protect against displacement is a high priority. New public spaces along the boulevard, designed with sensitivity to the dynamic cultures of East Austin, past and present, could become monuments to—and gathering places for—minority communities that are in some ways being negatively affected by the economic realities of a booming city with an increasingly popular core. At the same time, the reclaiming of access roads as developable land — which would increase residential supply closer to downtown — could, in the long run, help to meet the demand for affordable housing.

TxDOT is about to undertake an $8.1-billion renovation of a 66-mile stretch of I-35 in and around Austin, the cost of which would likely not vary significantly if the downtown portion were depressed instead of simply rebuilt. TxDOT’s estimates for the cost of capping these depressed lanes comes to $300 million. Local support—from neighborhood groups, civic organizations, boards and commissions, city council, the Chamber of Commerce, and the Downtown Austin Alliance—in conjunction with TxDOT’s planned renovation, makes for an ideal, once-in-a-generation opportunity to reshape downtown Austin by capping I-35.

Ironically, the construction of I-5 facilitated the removal of Harbor Drive. Once the new Interstate was built in 1966, Harbor Drive was viewed as redundant, and a citizen-based campaign, Riverfront for People, advocated for and successfully championed its removal and replacement with Waterfront Park.

When I-5 was constructed, Portland’s Central Eastside was primarily an industrial area. But in recent decades, many of the larger industrial businesses have decamped to other regional locations, and the area has transitioned into a wider mix of uses that combine offices and housing with small-scale industrial businesses and manufacturers.

The neighborhood has become a destination for locals and visitors alike because of its high concentration of breweries and distilleries. This transformation has been constrained by the freeway, leaving a major gap in activity and preventing the neighborhood from reaching its potential along the river.

The challenges for this neighborhood are only increasing with time. By 2035, Central Eastside is expected to grow by 7,000 households and 8,000 jobs. Such strong growth will put a premium on housing and likely will lead to rising costs, unless preventative measures are taken. At the same time, the neighborhood’s density will increase. More residents can live closer to their jobs, which lessens the city’s need for extensive highway infrastructure.

Central Eastside’s rapid growth makes this an opportune time to consider the removal of I-5, to be replaced by surface streets. The 43 acres gained through highway removal would increase business and housing opportunities, which in turn would help accommodate the area’s growth. Removing the freeway would enable the Central Eastside neighborhood to take better advantage of its existing transportation options.

Removing the highway would also create an opportunity to enhance the existing Eastbank Esplanade into a signature park in the heart of the city where people could enjoy the Willamette’s new accessibility via transit, through the regional bike network, and from the many residences and hotels that are within a 30-minute walk from the location.

Many ideas for transformation of I-5 at this location have been explored. Most recently, then-Mayor Sam Adams released a plan for a tunnel in 2012. However, a tunnel might add unnecessary expense—a combination of other routes in the city have the potential to support the traffic capacity of I-5. Interstate through-traffic could be rerouted to I-405, a short highway west of downtown that runs parallel to, and connects with, I-5 at both ends.

Groups like Riverfront for People have long campaigned for the removal of the elevated I-5 and current political momentum in the city is gathering against overbuilt highway infrastructure. The citizen group No More Freeway Expansions Coalition is working to block the ODOT’s expansion of I-5 in Portland’s Rose Quarter, just to the north of the Central Eastside. This is an opportunity to reconsider whether other parts of the highway are necessary. A redesigned Central Eastside riverfront, made possible by highway removal, is not hard to imagine. Portlanders need only look across the river.

I-64 runs the length of Louisville’s downtown waterfront, in many parts directly along the river’s edge. For decades, the highway has created a formidable barrier between the city and arguably its most significant amenity, its waterfront. While other parts of Louisville have enjoyed a revitalized waterfront, the same cannot be said for area between 22nd Street and the Clark Memorial Bridge. Here, the highway occupies the land directly adjacent to the water, with only a narrow riverwalk as greenspace.

Starting in 2005, citizen group 8664 campaigned to reclaim this land for the city. In place of I-64, Louisville would gain an expanded waterfront park with a parallel parkway. The four-lane parkway would be designed with pedestrians in mind, with frequent crossings, street trees on both sides, and a green median along its center. Although able to handle vehicle traffic, its primary goal would be to facilitate access to the waterfront to those who live, work, and visit downtown.

The transformation of this two-mile stretch along the river between I-65 and I-264 would free over 60 acres of land around many of Louisville’s landmark civic features, including the Muhammad Ali Center and the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory. Much of this land could be devoted to parklands and pedestrian access to the river, which would further strengthen the city’s cultural assets.

Private property owners would see benefits too. Where waterfronts have been carefully saved or reclaimed as public space, a zone of enhanced value radiates out from the waterfront for distances of a quarter to a half mile. For Louisville, this means an area of roughly 60 to 120 city blocks would rise in property value.

Furthermore, with a combination of tweaks to existing traffic patterns, the 8664 proposal meets demands for projected traffic volumes. Through-traffic along I-64 would be re-routed to I-265, Louisville’s outer beltway, which increases travel distances by only five miles. The combination of the new four-lane parkway and existing east-west streets along the riverfront corridor can handily accommodate the remaining 80,000 cars per day that use I-64 for local destinations.

8664 was formed in response to the Ohio River Bridges project, a joint venture by the States of Kentucky and Indiana that proposed the expansion of the Kennedy Memorial Bridge downtown and the construction of a second bridge eight miles upstream. 8664 opposed the expansion of the bridge downtown and saw this as an opportunity to re-envision the city’s waterfront as a place for people, not cars. Although 8864’s alternative fell within the bounds of the Ohio River Bridges’ environmental impact assessment and the group gathered the support of 11,000 petitioners, the $2.6 billion construction of the bridges proceeded unaltered.

Since its re-opening in 2016, traffic on Kennedy Memorial Bridge has decreased 49 percent, as drivers are hesitant to pay tolls up to $4 and instead have opted for free routes. There is, however, a silver lining to this underuse and overexpenditure on highway infrastructure: The same basic urban conditions that spurred the 8664 movement are still in place, and I-64 remains a prime candidate for removal in order to downsize infrastructure to a level appropriate for a mid-size city.

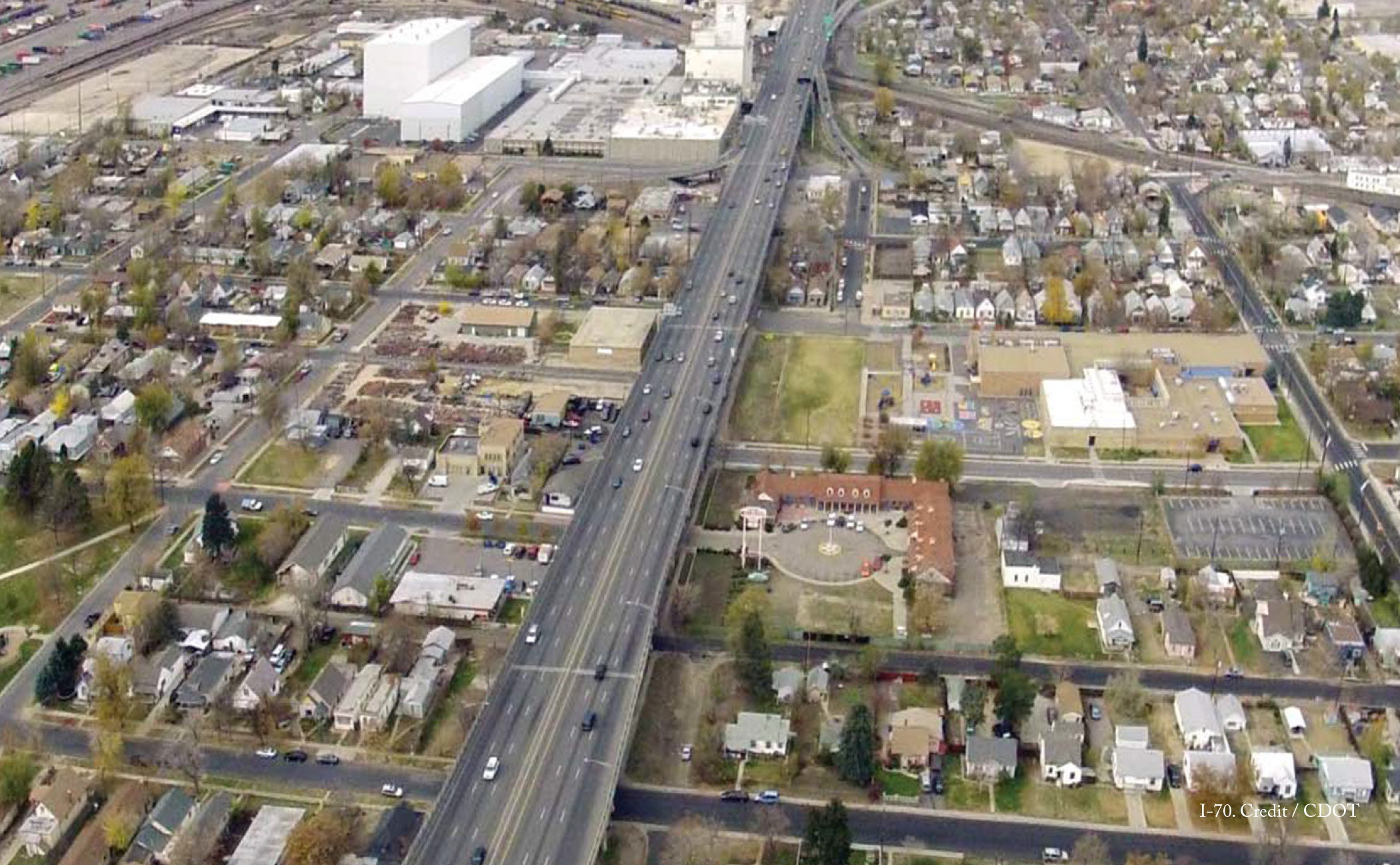

When I-70 was completed in 1964, the elevated highway diminished the value and changed the character of the primarily Latino neighborhoods along its course. Fifty-five years later, the aged viaduct is in need of significant repairs. Community organization Unite North Metro Denver proposed an alternative in place of the elevated highway. A tree-lined boulevard, with roundabouts instead of interchanges, would re-establish the community grid, free up land for development, and raise property values.

Instead, CDOT has so far opted to replace and expand the highway. In August 2018, it broke ground on the $1.2 billion Central 70 project, one of the most expensive projects ever undertaken by the agency. Over the next fifty to sixty months, CDOT will remove I-70’s elevated viaduct and replace it with a sunken freeway nearly three times as wide. The project has serious repercussions for the neighborhoods around it. To expand the highway, the state must seize and demolish 56 residences and 17 businesses, including one of the few groceries in the area. The plan also includes the demolition of Swansea Elementary School’s playground and the school building itself would be directly adjacent to the 14-lane highway.

When CDOT’s plan was revealed, a second community group, Ditch the Ditch, responded and raised environmental justice concerns. In addition to air quality issues, lowering I-70 below grade has the potential to contaminate groundwater sources, a fact that CDOT itself readily admitted when it shelved proposals to reconstruct I-70 as a tunnel.

In particular, Ditch the Ditch supporters took issue with CDOT’s proposed concession to the Swansea neighborhood. As a replacement for the demolished playground, CDOT proposed to cap a 4-acre area over I-70 and build a park above the highway. But with the rest of the road still uncovered, the children and others who used this greenspace would be exposed to the emissions from traffic below. The residents of the Elyria, Swansea, and Globeville neighborhoods, which all already belong to the most polluted ZIP code in the United States, would be subject to even more environmental hazards from the highway expansion.

With the support of the Sierra Club, several local organizations and neighborhood associations filed an injunction against the project on the grounds that it had not adequately addressed the environmental concerns for the community. As of December 2018, CDOT chose to settle the lawsuit and agreed to contribute $550,000 to an independent health study that will provide a greater understanding of public health and environmental hazards in the Globeville, Elyria and Swansea neighborhoods.

CDOT first proposed the reconstruction of I-70 in 2004. Fifteen years later, it runs contrary to recent transportation developments in Colorado. On the November 2018 ballot, voters turned down two proposals (Propositions 109 and 110) to allocate billions of dollars of funding to highway widening and expansion across the state. The state also elected Jared Polis as governor, who campaigned on the dual issues of cutting vehicle emissions and increased mass transit. In light of these developments, the Central 70 project appears to be behind the times—and proposals such as those by Unite North Metro Denver are more in line with current demands.

For over five decades, the elevated 1.4-mile stretch of I-81 known as ‘The Viaduct’ has split downtown Syracuse in half. The urban neighborhoods around the highway have suffered from its construction: It destroyed a historic African-American community, disrupted the flow of city streets, and paved over countless historic homes and sites. The disparity it has created between those who could afford to move to the suburbs and those who remained contributes to Syracuse’s high poverty rate.

But like many in-city highways, I-81 in Syracuse has reached the end of its lifespan. Now NYSDOT and city residents must decide its fate.

Grassroots movement ReThink81 has advocated that when the aged viaduct is taken down, it stays down. The movement offers an alternative for the city and has created images showing what the current viaduct corridor could look like without the highway. These visions emphasize streets on a pedestrian scale, rather than a boulevard with six or more lanes. None of the streets has more than four travel lanes; all include ample sidewalks, with at least one bike lane separated from fast-moving traffic by on-street parking. In this scenario, Interstate traffic would be rerouted around the city via I-481, which would be renamed I-81. With the viaduct gone, local traffic would be dispersed through an enhanced street grid system.

These common-sense designs have won over many supporters. Hundreds have attended rallies in support of the community grid. Nearly 20 local organizations and associations have joined the Moving People Transportation Coalition, to increase awareness of the advantages of the community grid. Syracuse’s primary local newspaper, The Post-Standard, published a front page editorial last July—its first in 37 years—titled “Let’s unite Syracuse: Replace I-81 with a community grid.”

The idea has also gained traction at the political level. Recently elected Syracuse Mayor Ben Walsh campaigned with the community grid as part of his platform. But he was far from alone; three of the four mayoral candidates last election came out in favor of the grid—as a group they garnered well over 90 percent of the vote—and Common Council is also on board. Even New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has weighed in, calling the elevated viaduct “a classic planning blunder.”

The community grid option also has social and economic upsides for the city. The removal of the highway has the potential to return up to 18 acres of developable land to the city. The American Institute of Architects I-81 Task Force estimates that redevelopment of this land could result in the creation of $1.5 billion in property value and $3.6 million annually in tax revenue.

This redevelopment is an opportunity to create more inclusive opportunities for the members of Syracuse’s community historically left out of the system. The Syracuse Housing Authority, which already owns land along the I-81 corridor, foresees being able to add another 600 below-market-rate units.

Because of the identifiable benefits and extensive support for the community grid option, NYSDOT is considering it as one of two options for the replacement of the I-81 viaduct. A decision ten years in the making is imminent, as is the opportunity to revive the bustling streets of Syracuse’s past.

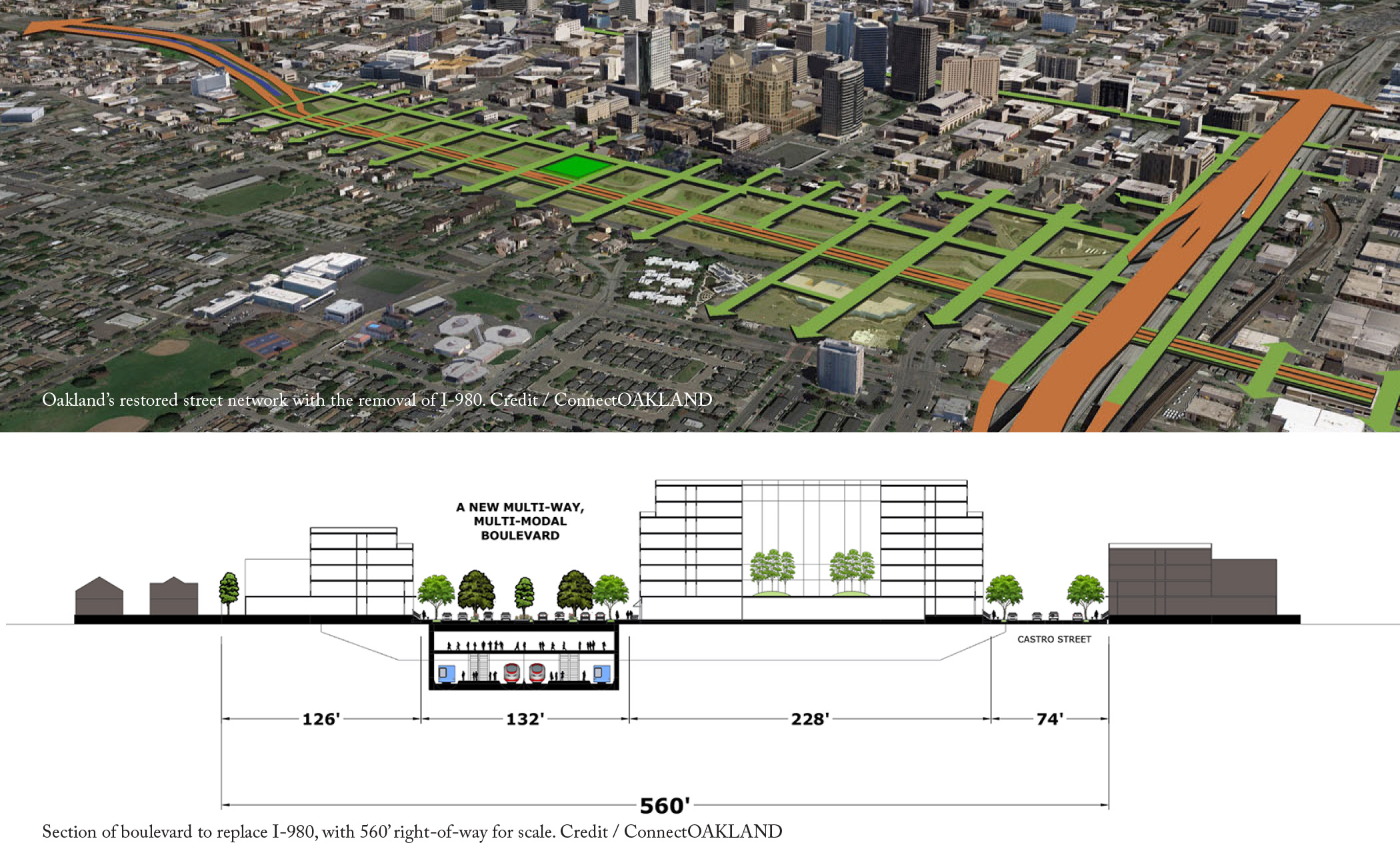

The economic benefits promised as part of this highway’s construction failed to materialize. Instead, the West Oakland neighborhoods adjacent to I-980 experience some of the highest asthma rates in the state of California (in the 99th and 100th percentile) and have notably poor access to healthy foods. Meanwhile, less than a quarter mile away across I-980, Uptown Oakland is undergoing a renaissance. West Oakland residents should be able to walk to Uptown’s services and amenities, but are effectively cut off by a daunting route that consists not only of the Interstate highway, but also a pair of frontage roads that serve fast-moving traffic. The right-of-way for all of this asphalt is an enormous 560 feet wide.

Caltrans acknowledges that the current number of lanes is excessive to accommodate the 92,000 cars per day that travel the road, a volume that accounts for only 53 percent of possible capacity. Most of these vehicles are local traffic, with both origins and destinations along the northern part of the corridor. Most trucks that prefer wide lanes to service Oakland’s port already opt for I-880 over I-980. A surface boulevard integrated into a street grid along the route of I-980 would have the capacity to handle the traffic in a more suitable fashion.

The citizen group ConnectOAKLAND calls for replacing I-980 with a boulevard that has capacity for transit and bike facilities. The I-980 footprint has the potential to build a strong foundation for regional mobility, especially if connected to existing public transit networks like BART and Caltrain. ConnectOAKLAND’s vision includes taking advantage of I-980’s depressed lanes to create multi-level transit infrastructure and avoid costly tunneling or seizure of private property. The right-of-way for the proposed boulevard would be 75 percent narrower than the highway, making pedestrian crossing easier.

The transformation of I-980 offers other important benefits for the city. The creation of a boulevard will stitch the former street network back together with as many as 15 cross streets and, in the process, create new real estate adjacent to downtown. The boulevard solution reclaims seven western blocks that I-980 encroached upon, and creates 14 new city blocks to the east—around 17 acres in total of publicly controlled urban land. This new land could be developed for any type, use, or intensity that will best serve the interests of Oakland’s residents, including affordable housing and community services.

With this proposal in hand, ConnectOAKLAND has engaged private, public, and professional stakeholders. Many local leaders and community activists in West Oakland support the plan and Mayor Libby Schaaf has championed the removal of this underutilized section of highway. The City of Oakland is now exploring the replacement of I-980 with surface streets as part of its Downtown Oakland Plan. Although much work remains to be done, the removal of I-980 would advance many community goals while opening up opportunities for equitable development.

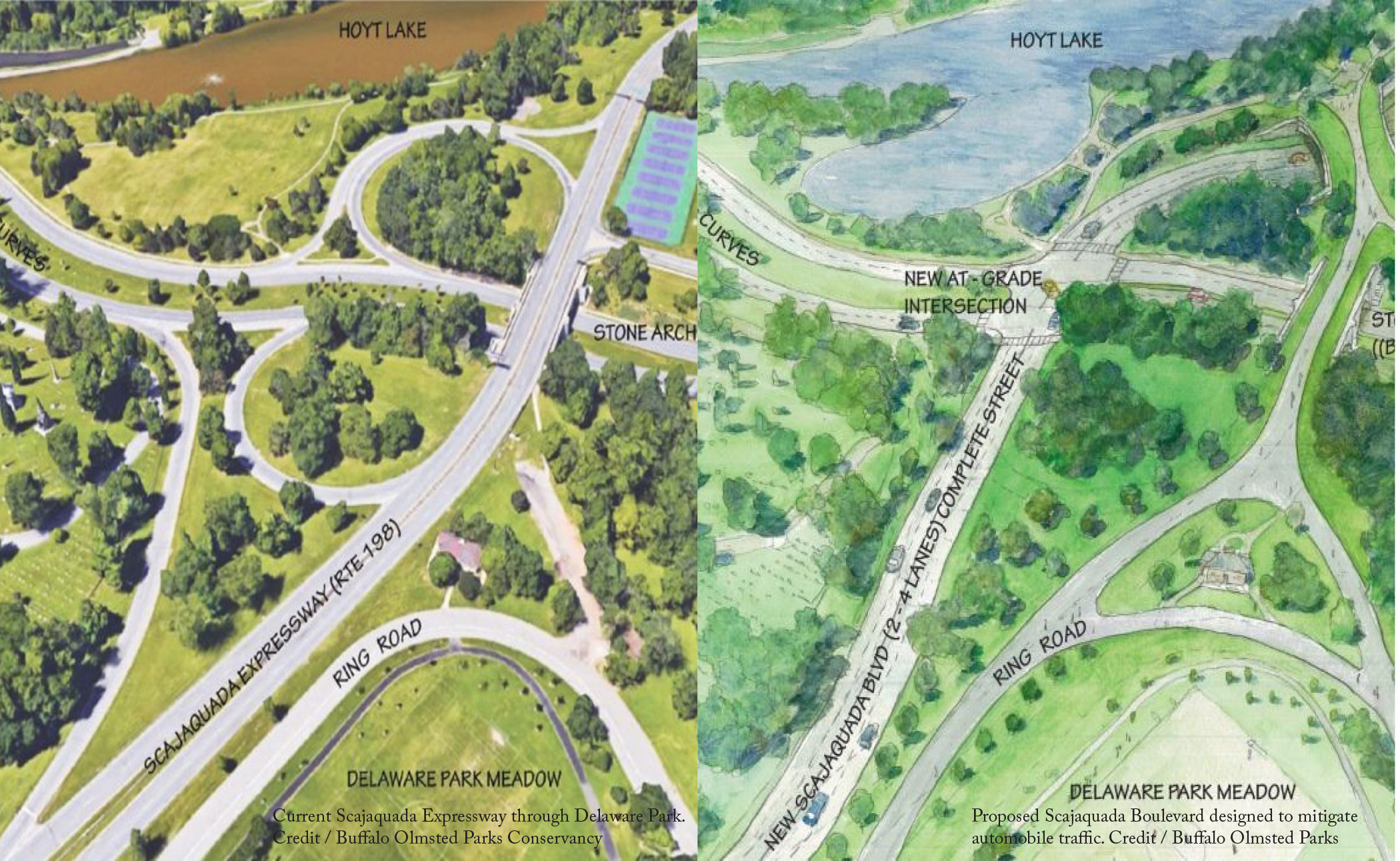

Not only did this pair of expressways deprive Buffalo of quality parklands, but it also severely damaged the neighborhoods along these corridors. The demolition of thousands of homes and businesses in Buffalo’s East Side to make way for the Kensington Expressway displaced city residents, while NYSDOT seized parts of Delaware Park on the justification that it was “vacant land.” Property values in the Hamlin Park neighborhood, situated where these two highways connect, plummeted and remain among of the lowest in the city. Many local businesses in the nearby Jefferson and Fillmore business districts were shuttered as residents moved away.

Fortunately, many of the assets near the expressway corridors remain relatively intact. Humboldt Park (renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Park) endures as the home of the Buffalo Museum of Science. The present-day park reflects the city’s African-American heritage and hosts its annual Juneteenth Festival. The now-bisected Delaware Park is still a popular destination within the city.

Many local organizations, including the Restore Our Community Coalition, the Scajaquada Corridor Coalition, and the Olmsted Parks Conservancy are working together to restore the original Olmsted parks system through context-sensitive solutions.

These groups support a NYSDOT proposal to cover a one-mile stretch of the Kensington Expressway to reconstruct the former Humboldt Parkway. This proposal re-connects the neighborhoods divided by the depressed highway and creates a pedestrian-friendly environment by relegating fast-moving traffic to the underground lanes.

The parkway would return 14 acres of land to the community and generate opportunities for infill development and affordable housing. In turn, reinvestment to the Jefferson and Fillmore business districts could create up to $2.8 million in new property tax revenue for the City of Buffalo over a 30-year period, in addition to $76.7 million in household wealth.

Community members also advocate for a transformation of the Scajaquada Expressway into a tree-lined boulevard/parkway to reduce noise and pollution, increase safety, and reconnect adjacent neighborhoods’ access to the park. The vision pays homage to Olmsted’s original plan and would consolidate the cultural assets, now separated by the highway, that border the park. These assets include the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and the Buffalo History Museum, which would be within walking distance of each other—if not for the four-lane barrier.

Thanks to the combined efforts of Buffalo’s community organizations, NYSDOT withdrew their proposal last January to rebuild the Scajaquada corridor using highway-like design with limited traffic calming measures. Instead, it will reconsider community-based designs. Stephanie Crockatt, Executive Director of the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy, hailed the decision as a benefit to Buffalonians now and in the future: “Today we can say clearly that the community has been heard. Thanks to the effort of so many concerned citizens who worked so hard over these past several months, we now have an opportunity to restore the jewel of Olmsted’s system.”

On Friday, January 11, 2019, the City of Seattle began the process of dismantling the elevated Alaskan Way Viaduct. This freeway had long separated much of downtown Seattle from its waterfront. By the turn of the millennium, it had reached the end of its lifespan. Seattle had committed to its replacement with a boulevard as early as 2007, but in 2009 the State of Washington decided to add a costly highway tunnel with an initial price tag of $3.1 billion. In the month between the closure of the viaduct and the opening of the tunnel in February 2019, the predicted ‘carmageddon’ caused by the highway’s removal failed to manifest, which suggests that the tunnel was an unnecessary expense.

In December 2017, the dust began to settle from Rochester’s Inner Loop East project, the decommissioning and infill of a portion of the freeway that ringed downtown. Since its completion, Rochester has witnessed the benefits of the freeway’s removal. Three major mixed-use developments that include below-market-rate apartments have already broken ground and another two projects are already in the pipeline. One of these includes a partnership with local healthcare provider Trillium Health, with plans to dedicate 20 units to supportive housing programs that aid its formerly homeless clients. Rochester is seeking to capitalize on this momentum and is currently studying the removal of the remaining parts of the Inner Loop.

The Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) has formally committed to the removal of I-375 through downtown Detroit. The project probably will not commence until around 2022, as MDOT explores design alternatives. Currently, it has settled on two options, both variations on a boulevard design. However, both designs still cater excessively to automobiles and very much resemble the freeway they will replace. Each features a total of eight travel lanes (four northbound and four southbound), which exceeds the number on the current highway. MDOT needs to consider more pedestrian-oriented designs, if Detroit is to reap the full benefits of highway removal.