History and Context

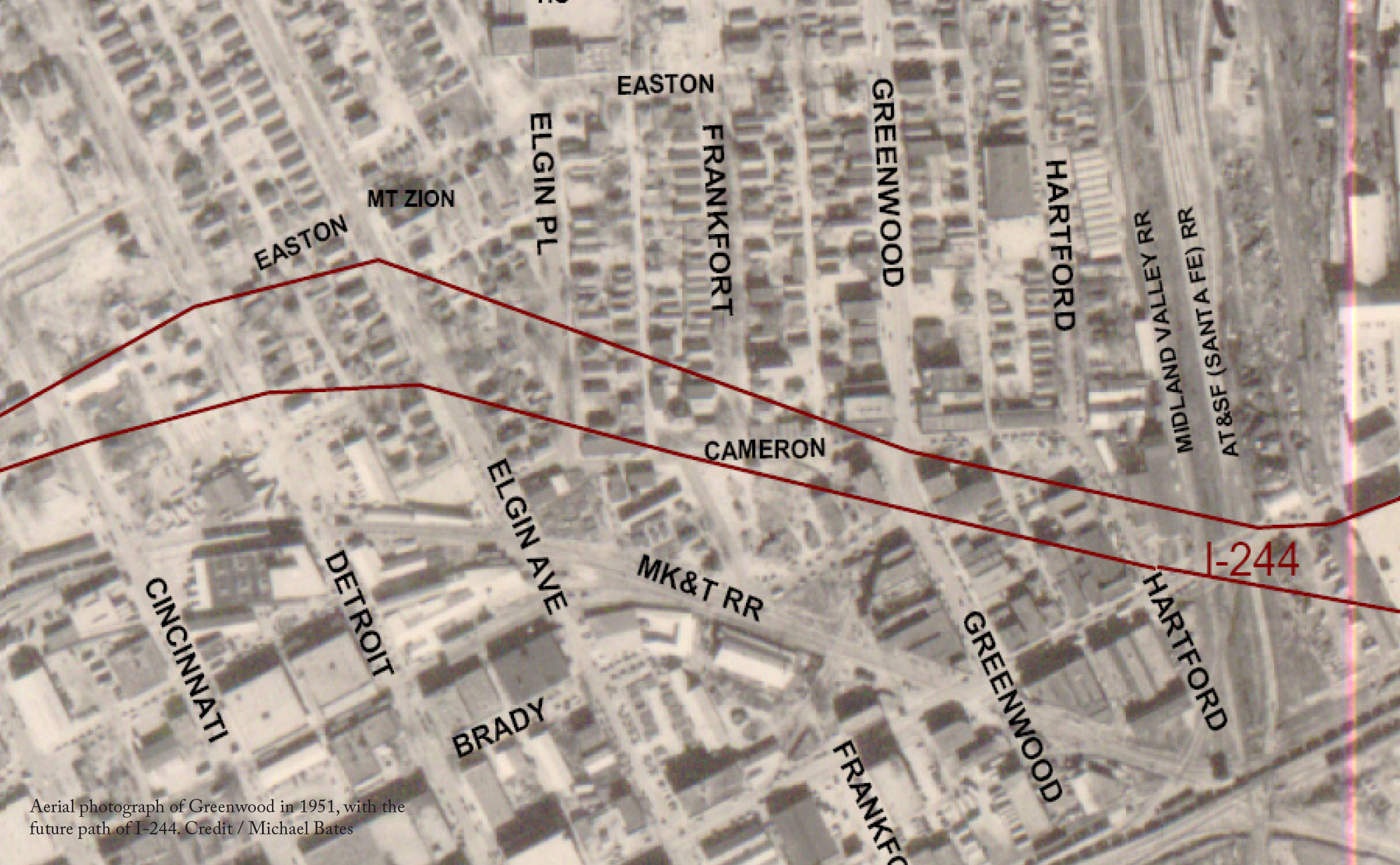

Interstate 244 runs directly through Tulsa’s Greenwood district, the historic center of the city’s African-American community once known famously as ‘Black Wall Street’. In 1921, a mob of white Tulsans, provoked by misleading newspaper headlines, descended upon Black Wall Street, killing at least 100 people (but likely many more) and destroying the 2019 equivalent of more than $32m worth of property. Greenwood’s Black community quickly reestablished itself and returned even more triumphant, only to be razed again decades later by highway builders.

With the end of legal segregation in the early 1960s Greenwood’s businesses had experienced a bit of a decline, as Black spending was no longer concentrated exclusively in the district. But it still remained a source of community pride. I-244’s construction put an abrupt end to any potential revival. The businesses in the highway’s path closed or relocated elsewhere, away from their traditional customer bases. In 1942, Greenwood was home to 242 Black-owned businesses spread over 35 square blocks. The highway reduced that number to only a handful, most situated on the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue, which local attorney E.L. Goodwin, Sr. had saved through negotiations.

Proposal

Today, I-244 in Greenwood forms the northern part of a series of highways known as the Inner Dispersal Loop (IDL) that cordons off downtown from the rest of Tulsa. Parts of historic Black Wall Street remain in its shadow, including the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue (also known as Deep Greenwood) and a pair of churches (the Mt. Zion Baptist Church and Vernon AME Church) that were burned down during the race massacre but rebuilt afterward. Just north of the highway is the Greenwood Cultural Center, built in 1980 to celebrate the achievements of Black Wall Street residents and remember the tragedy of the race massacre.

These community assets could serve as the foundation for a revitalized Greenwood following the removal of the northern section of I-244 along the IDL. The concept is a nascent one, but the Tulsa Regional Chamber, Historic Greenwood District Main Street, and other local advocates think it is worth exploring. I-244 acts as a physical barrier between predominantly Black north Tulsa and historic Greenwood Avenue and downtown to the south. By removing the highway and restoring street connections, north Tulsans would be able to more easily walk or bike downtown, and business owners in Deep Greenwood would benefit from increased traffic. New land would also be available to expand Deep Greenwood northward, where it is largely constrained by the presence of the highway.

Of course, the removal of I-244 alone won’t restore Black Wall Street. But coordinated reparative programs, coupled with the highway’s removal, can support community efforts to build a new Black Wall Street. This includes programs to help develop new Black-owned businesses and boost existing ones, leveraging the City’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund to create affordable homes within walking distance, and establishing a community land trust to rehabilitate vacant lots and abandoned houses in line with residents’ interests. It will take focused investments and intentional policies like these to rebuild an expanded Greenwood district that does justice to historic Black Wall Street, while also addressing displacement concerns.

This year marks the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre, when Black Wall Street was first destroyed. Now would be a fitting time to carry forward a conversation about I-244’s removal. Preliminary investigation suggests it is more than feasible. This one-mile segment of I-244 is hardly essential for regional travel and Tulsa has a second loop highway, the Gilcrease Expressway, only a few miles to the north. The outstanding question is how to best ensure the highway’s removal and a subsequent restoration of Greenwood helps Black Tulsans heal and thrive.