From slogan to substance, planning the 15-minute city

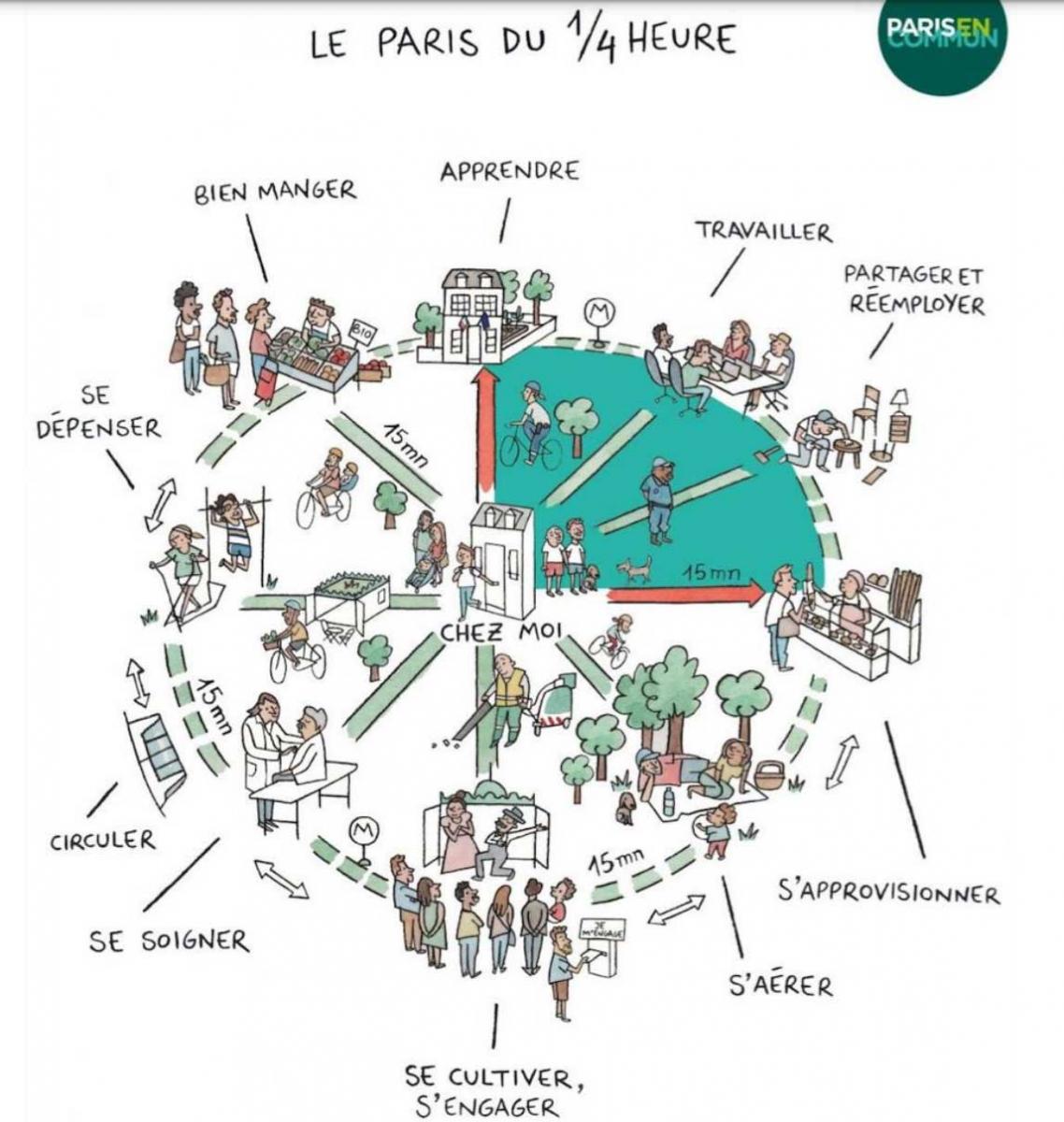

Chances are you have heard of the 15-minute city—which has become a common marketing slogan in urban planning and development in the last two years. The 15-minute city is important because it places human-powered access to goods and services at the heart of community planning. Hence, the 15-minute city is often described as a mixed-use, walkable metropolis where you don’t need a car to meet your daily needs.

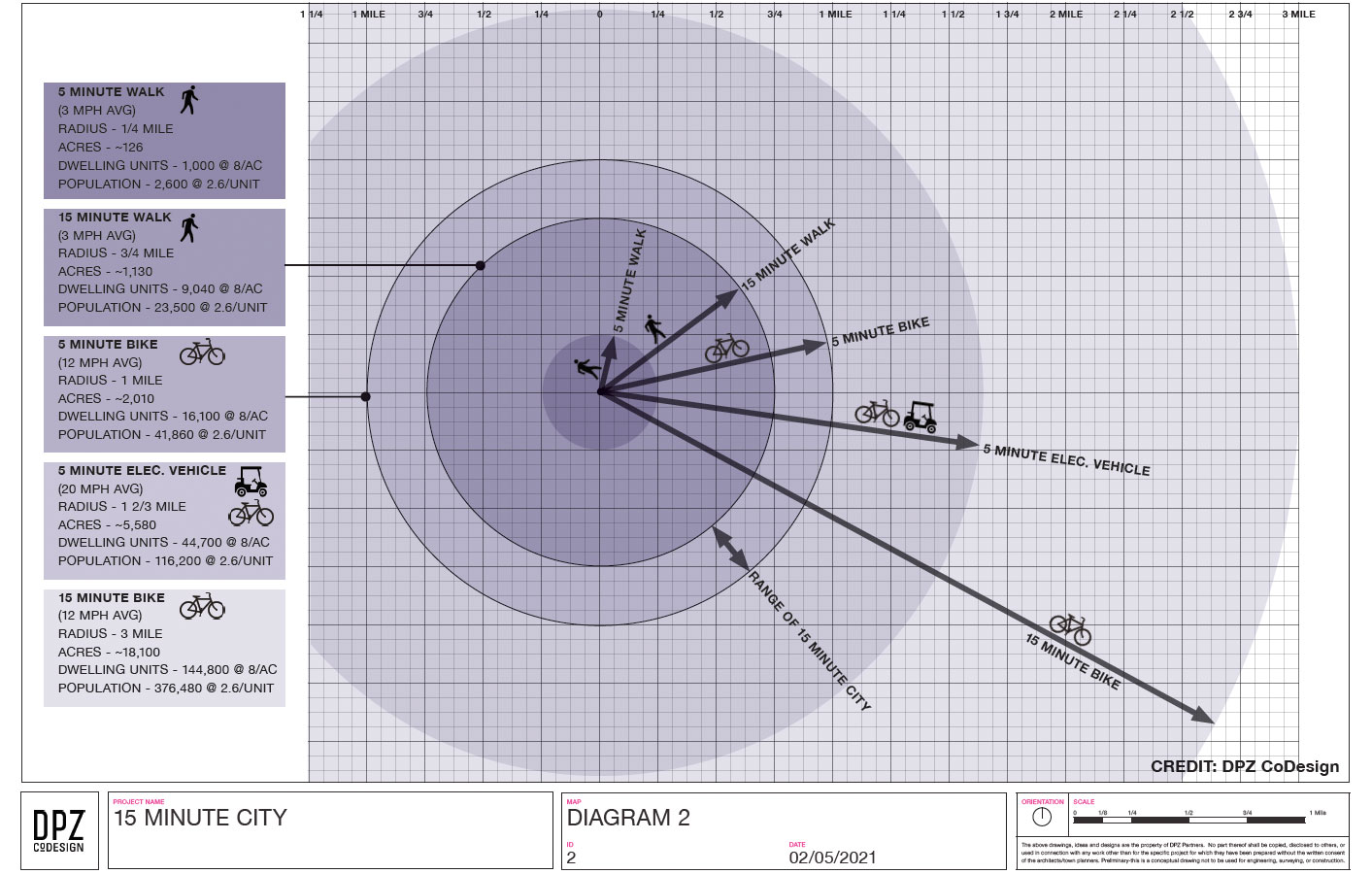

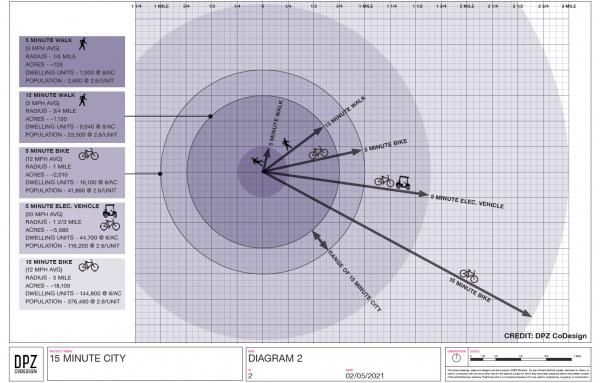

Unfortunately, some descriptions stop there—and fail to seriously examine how 15-minute cities could be organized. To ensure that they can be truly planned and implemented, and to distinguish the concept from marketing, the geographic aspect must be better understood. The 15-minute city is actually composed of nested, human-powered transportation sheds. These sheds range from the neighborhood to the regional scale, with every level requiring a diversity of people and activities.

This essay builds on a previous essay, “Defining the 15-minute city,” by Andres Duany and Robert Steuteville. That essay defined the concept in term of transportation sheds, and this essay looks closer at what is needed within those sheds. The two essays are best understood when read as a pair.

For 30 years, new urbanists have been promoting walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. The 15-minute city takes that idea to a new level, by proposing how neighborhoods, districts, corridors, parklands, and natural features may be combined to enable relatively self-sufficient urban lives. The metric of time applied to walking and biking imposes a spatial discipline that makes the concept useful and meaningful.

The 15-minute city is compatible with other new urbanist theory, such as the principle of the five-minute pedestrian shed, Speck’s general theory of walkability (a walk must be useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting), and the rural-to-urban Transect, which shows how to provide cultural as well as functional diversity.

The idea contrasts with how cities have been planned for much of the last 70 years—when automotive transportation has been the organizing factor. In practice, this has meant separating uses and housing types, and building roads between them. Such communities lack any kind of spatial discipline.

As we described in the previous essay, three kinds of sheds principally comprise the 15-minute city: the 5-minute pedestrian shed, the 15-minute pedestrian shed, and the 15-minute bicycle shed. Let’s explore them, and their hierarchy of activities, in more detail.

The 5-minute pedestrian shed

This shed has been standard practice in New Urbanism since the 1980s. It is observable as the structure of most intact traditional cities and towns. The size and shape of neighborhoods vary, but most are about a quarter mile from center to edge—a size of about 125 acres. The five-minute walk is well-known, but still deserves a brief description here because it is important to the larger 15-minute city.

Ideally, residents should be able to obtain such daily needs as basic groceries and household items, access a “third place” like a coffee shop or tavern, and reach services like a laundromat or dentist within a few blocks. The neighborhood should have an elementary school and houses of worship and perhaps a community building. One or more public green spaces should be provided.

The 5-minute pedestrian shed also requires a diversity of housing, including “missing middle” types, and a wide range of price points, including rental and homeownership. Based on scores of housing studies, a mix to meet broad housing needs and market demand may be summarized as one-third each of apartments, townhouses, and single-family units. This shed should include affordable housing, either naturally occurring or subsidized.

The 5-minute pedestrian shed should consist of two or three Transect zones—especially neighborhood center and neighborhood general, and perhaps sub-urban.

This neighborhood is small compared to the 15-minute city, and yet it is a complex enough organism. Theoretically, there could be scores of distinct neighborhoods in the 15-minute area. This creates a lot of redundancy, which is important for community resilience. For example, there could be dozens of corner stores in the 15-minute city, with a variety of cultural specialties and socially-based price points.

The 15-minute pedestrian shed

Neighborhoods are strengthened when they overlap other neighborhoods in the 15-minute city. What one neighborhood lacks, the next one over may have. The 15-minute pedestrian shed combines up to seven neighborhoods, and also may include districts, focused on a single purpose (e.g., academic, medical, or commercial). These neighborhoods should be connected in a continuous urban fabric. Larger, mixed-use centers shared by neighborhoods support more retail.

This size catchment would support one urban center, such as a main street, with significant job base. The urban center may contain mid-sized employers and a great variety of services and civic facilities that could not be found in a single neighborhood.

Among the many diverse elements in the 15-minute city, employment is crucial because it connects individuals to livelihoods and the regional economy. In the 15-minute city, many of these connections are located nearby, and therefore within the range of a 15-minute walk or bicycle ride.

Most businesses in the US today, including industrial operations, are compatible with residential uses. Operations that employ large trucks as a primary activity are an exception. Businesses such as large grocery stores that require the occasional 18-wheeler—no more than one at a time—may still be placed within an urban center with nearby living spaces if appropriately designed.

The 15-minute pedestrian shed will have a diversity of neighborhoods, and each neighborhood will have its own diversity. Diversity at the neighborhood, 5-minute-walk, level is important to keep the 15-minute city from becoming segregated along racial and class lines.

The 15-minute pedestrian shed will include corridors connecting neighborhoods, and perhaps bike-ped trails, which are becoming an important focal point for development in cities (see The Beltline in Atlanta, and The Highline in New York City). These corridors could take the form of bike lanes, or transit corridors. Bicycle planning is critical to the 15-minute city.

Planning the 15-minute pedestrian shed, covering 1.75 square miles, is crucial. If it’s not easy to build or revitalize an individual neighborhood—doing so in an area that is seven times larger poses challenges. These challenges include high-speed corridors, “b streets” with anti-pedestrian surface parking, and areas where the walk is generally not safe, comfortable, or interesting. Identifying and overcoming these problematic barriers is key.

Coincidentally, the 15-minute pedestrian shed is similar to the area covered on a bicycle in 5 minutes. The corresponding 5-minute bicycle shed is useful for trips to the grocery store, school, clinics, and government buildings. This size shed will include a full patchwork of Transect zones—and greater diversity than a single neighborhood.

15-minute bicycle shed

If a 15-minute bicycle shed also defines the total geographic area of the 15-minute city, the prodigious scale of this catchment is important to fully grasp. It may encompass up to 28 square miles, which is as big as a mid-sized city.

Such as area would contain several urban centers and myriad neighborhoods—difficult to weave together in a continuous tapestry of urban blocks and streets. Yet the main requirement stays the same—the requisite diversity is finely grained.

Then, this shed warrants a high school and a variety of specialized districts, including warehouse districts and college campuses like universities. Although specialized in use, such districts should engage the network of urban blocks. Beyond excessive parking, there is no inherent incompatibility with the 15-minute city.

Hospitals and medical centers are another major employment category (the core economy of some cities) that should exist within the geography of the 15-minute city. Hospital-oriented development (HOD) mixes residential and commercial uses that are symbiotic to the medical economy—also serving the adjacent neighborhoods.

Still other districts provide facilities that are incompatible with residences. These include distribution centers, groups of big-box stores, and industries with noise and vibrations. At a reasonable scale, these may be sited within a few blocks of residential areas. Such operations offer working-class job opportunities, important to diversity. These uses contribute to a more socio-economically equitable community.

Residents of the 15-minute bicycle shed should find access to a broad range of cultural and entertainment amenities. Performing arts, galleries, and sports facilities can be supported by the population located within those square miles. Districts are good locations for outdoor music, breweries, and nightclubs that would be too noisy for nearby living spaces. These edgy “third places” often attract a diverse crowd, and they are useful for social mixing of the young, who will not long remain in a community without a nightlife. Radical diversity of wealth, class, age, race, political affiliation, career choice, and education level needs places to mix—and musical entertainment is a solvent for that ideal.

The 15-minute city allows a balance of nature and urbanization. Too much open space will undermine the amenities that attract people to the city in the first place—but appropriate levels of open space are inserted at every scale, some of regional importance. Apart from the expected squares and plazas for festivals, larger parks could be connected to natural features. The 15-minute city ideally offers human-powered access to the countryside through regional trail systems. High schools may also provide community playing fields, libraries, meeting halls, and performing arts venues.

Any hand-tended food production such as an orchard, vegetable farm, or community-supported agriculture (CSA), may be located within the 15-minute bicycle shed. The bicycle shed could easily include at least one farmer’s market.

Beyond human-powered transportation

Human-powered transportation is more affordable. Thereby socio-economic equity is supported when people can get around without an automobile. And yet, for the purposes of transporting goods and people with special needs, engine-powered transportation must be accommodated.

For example, jobs should be plentiful in the 15-minute city—yet some people will need to commute longer distances and should have the option of using bus transit lines throughout 15-minute cities. Each 15-minute city should be penetrated by regional transit lines, but there also may be commuter rail transit at the edge.

E-bikes and other small electric vehicles are a useful accelerator for human-powered transportation in the 15-minute city. E-bikes, especially, have the advantages of bicycles in terms of health and sustainability, but can go farther faster. E-bikes may overcome some geographic barriers, such as hills. They can also help riders who are not as fit, such as senior citizens, fully enjoy the benefits of 15-minute cities.

Automobiles are still important in our economy, and thus play a role in the 15-minute city. The 15-minute motor vehicle shed covers 10 miles in radius, or about 300 square miles. Larger transportation sheds that reach vital resources like food, water, and energy supplies, are important to the 15-minute city—and they should be mapped and understood by the broad public. DPZ CoDESIGN has explored the idea of catchments for resources in A General Theory of Urbanism. For purposes of resilience, residents should be aware of where their resources come from. A “food shed” should be accessible by truck in 15 minutes. Larger-scale agriculture, such as grain production that requires tractors, may have to be in the truck farm food shed (10-mile radius).

Density and the 15-minute city

All such aspects of human needs, in a limited geographic area, implies compactness. Density is necessary to provide diversity within appropriate sheds of the 15-minute city.

And yet, measurements of density are often confusing as they, too, lack clear definitions. The radical difference between net density, and gross density, is poorly understood even by land-use professionals. Net density doesn’t include streets, public and undeveloped land, nonresidential sites and buildings, districts, and other uses. It can therefore achieve very high numbers. For example, a single building that is 100 or 200 units to the acre is not unusual. Even a site with low-rise housing types may amount to 30 or 40 units per acre.

The 15-minute city, however, is measured by gross density, which comprises everything within its borders including districts and major natural features, which can take up a lot of land. Cities that fit the “15-minute city” mold vary considerably in gross density. Excluding New York, which is an outlier at about 20 dwellings/acre, the gross density of many big, traditional US cities ranges from 7 to 9 dwellings per acre (Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and DC fall in that range). Many other cities—still walkable and mixed-use—have lower gross density. Ithaca, New York, for example, boasts one of the highest walk-to-work numbers in the nation—more than 40 percent—and incorporates many characteristics of a 15-minute city. Yet the gross density of Ithaca is around 4 units per acre.

We believe the bottom line is this: 15-minute cities should strive for a gross density of at least 8 units to the acre, excluding districts and major environmental features. In sum, a community doesn’t have to be a Paris, New York City, or Barcelona, to meet goals of the 15-minute city. Small American cities, towns, and suburbs, with their low gross density, may still strive toward the 15-minute city model.

Applying the 15-minute city broadly

Paris, France, is considered the 15-minute urban ideal, and the concept has been fully embraced by that city’s municipal government. Paris sets a standard for quality urbanism that few American cities can approach—places like New York City, Boston, DC, San Francisco, and Seattle, in part, may get close. Yet, the 15-minute city could have far wider application than just cities of international renown.

For example, Buffalo, New York, has room for several 15-minute cities within its borders. The strongest would be centered on downtown and encompass the Medical District, the waterfront, other employment districts, and interwoven neighborhoods. Another could be found in North Buffalo, encompassing the University at Buffalo, several hospitals, the Buffalo Zoo and Delaware Park, and surrounding neighborhoods. The city could plan for a few other 15-minute cities to emerge over time through policy and vision. Buffalo houses 278,000 people, but at its peak had a population of nearly 600,000. The promise of becoming a 15-minute city is a framework for Buffalo to recover some of that lost population and economic vitality.

We recently explored Auburn, New York, a city of 26,000, as an overlooked example of a 15-minute city. The city is small enough that its entirety easily fits within a 15-minute bicycle shed. Downtown is at the center of four quadrants, each with multiple neighborhoods and districts. Auburn has a version of nearly everything that is needed for living—employment, education, health care, retail, government services, parks and recreation, entertainment, culture—within 15-minute cities.

Some urbanists argue that the 15-minute city cannot be achieved in US suburbs. Given time and the right policies, even conventional suburban environments may benefit from the spatial discipline of the 15-minute city. The Blue Line Corridor in Prince George’s County, Maryland, is an example of how that could happen. The county is fortunate to have four Washington Metro commuter stations on the corridor, where plans are to implement transit-oriented developments (TODs). The Blue Line Corridor, largely funded, is destined to be built, by infilling urbanism around suburban neighborhoods built in the last 50 or 60 years. The transit infrastructure helps to make this possible, and the transformation may be credited to visionary elected leaders who built an economic development strategy around urbanism.

Conclusion

The 15-minute city is a powerful idea, because it places diversity and human access at the center of community planning. In the 20th Century, we learned the mistake of organizing cities and towns around the latest transportation technology, rather than people. Twenty-first century cities may accommodate new technologies, but not at the expense of walking or pedaling.

It is vital that planners and public officials understand what the 15-minute city means. It takes the idea of a walkable neighborhood, with access to daily needs, and applies that to a much larger scale towards all needs within nested, human-powered transportation sheds.

The 15-minute city is a worthwhile model that most communities may strive for. The more human needs that are provided within the access of quarter-hour human-powered transportation sheds, the stronger the cities will be economically, socially, and environmentally.

The 15-minute city is not easy to achieve, because of the barriers and distribution of 20th Century transportation and zoning codes. By reforming these outdated transportation systems and regulations, communities can begin to apply the principles of the 15-minute city.