In October 2011, the city of Montgomery, Alabama played host to CNU's New Urban Council VIII. A contingent of over 50 dedicated New Urbanists convened to examine the state and shape of New Urbanism to come. The successes and failures of past projects - and the potential of future initiatives to improve the quality of the built environment - were explored through lectures and in a give-and-take format. Through project critiques (such as Victor Dover on DKP's Downtown Montgomery Plan and Nathan Norris on The Waters), an assessment on Sprawl Retrofit from Ellen-Dunham Jones, a discussion led by Todd Zimmerman on the emerging demographic collision between the baby boomers’ and millennials' demand for urban environments, and a presentation on harnessing form-based coding as an economic development tool by Scott Polikov, the council provided a forum for dissecting CNU's progress.

The setting of Montgomery allowed participants to experience some of the positive developments currently happening in the historic city, including a tour of the DPZ-designed community Hampstead, a riverboat cruise, and a special farm-to-table dinner at the Hampstead Institute Downtown Farm.

Victor Dover-Downtown Montgomery Plan

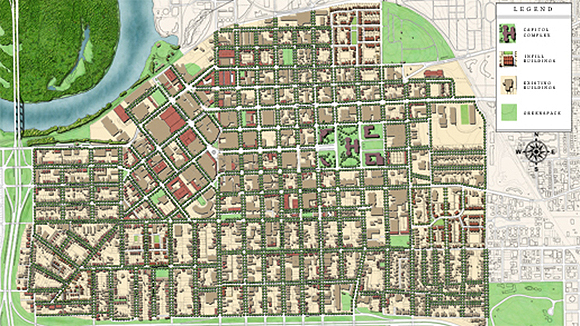

Victor Dover put the setting of this year’s council in context by discussing the creation of DKP's Downtown Montgomery Plan. Following a design charrette DKP held in Montgomery, fundamental ideals were prescribed to bring the downtown area back to people-oriented urbanism:

- Preserve, Restore, Reuse

- Unleash Private Investment

- Make it Green

- Mix uses, housing, and building types

- Insist upon Balance

Practical implementation of these broader themes involved use of the Montgomery Smart Code, reduction in the amenity and civic space requirement, reduction in land for Traditional Neighborhood Developments, allowance of additional uses downtown, use of a transect map for infill development, climate succession, incorporation of additional road types, use of a synoptic survey for local calibration, and conservation of historic structures.

Dan Camp's Response to Downtown Montgomery Master Plan: Incremental is Everything

Dan Camp's Response to Downtown Montgomery Master Plan: Incremental is Everything

In the Cotton District of Starkville, Mississippi, Dan Camp undertook a redevelopment project starting with eight units close to the Mississippi State University campus. As the development thrived, he bought more small increments of space for infills. “Incremental development gave my work and me the ability to be financially independent,” Camp stated.

By doing everything in-house and in small steps, Camp never lost control of his development to government programs or other firms. Camp designed small retail space (16 x 24 ft.) with living spaces above. The commercial spaces could be rented for small amounts which helped to outlay initial extreme costs and to provide an income stream to help with the rest of the eventual development.

Drawing from his experience in Mississippi, Camp believes the central question for Montgomery’s development plan to be: “Where are all the people?”

The incremental development strategy could be successful in Montgomery if the demand is there, he said. Though development codes are strict, the city council is not an insurmountable obstacle in designing new neighborhoods if developers stick to their plans. Other problems in Montgomery include wide streets, low city funds, and excessive parking. Despite its early streetcar adoption (and subsequent decline), Montgomery grew up prioritizing personal transport. However, investors are catching on to the need for an incremental, dense, downtown approach to the city. It is most important to get local officials to start thinking about what adds value to city streets. There is often a fundamental disconnect between city officials and state or federal officials. The state and national governments see the street as a means for longer-distance transport. To the city, however, the market and social aspects of the street mean much more. It’s essential for the public works departments to be more city-oriented.

Here, the question of financing becomes entwined with that of theoretical demand. Public works still has more money than planning departments, but as municipalities see themselves less as federal agencies and allow private capital improvements to take on more city developments, everything is slowly moving in the right direction.

Todd Zimmerman: The Next Great Market after the Great Discontent

Former CNU Board member Todd Zimmerman commented on the breadth of generalizations being made when talking about new development. Calling America the “land of self-invention,” Zimmerman sees the future of housing options reflecting the diversity of the population. Realtors will see that we are in the midst of a Great Convergence (2004-2024), a demographically-defined era during which the baby boomers, who are more likely to own than rent, meet the millennials, who are more likely to rent than own, in the housing market. Both groups are trending towards mixed-use, walkable housing at all scales. Immigrants, who once settled in gateway cities, are now filling the gaps at the urban fringes and represent a significant percentage of buyers of suburban tract housing.

Former CNU Board member Todd Zimmerman commented on the breadth of generalizations being made when talking about new development. Calling America the “land of self-invention,” Zimmerman sees the future of housing options reflecting the diversity of the population. Realtors will see that we are in the midst of a Great Convergence (2004-2024), a demographically-defined era during which the baby boomers, who are more likely to own than rent, meet the millennials, who are more likely to rent than own, in the housing market. Both groups are trending towards mixed-use, walkable housing at all scales. Immigrants, who once settled in gateway cities, are now filling the gaps at the urban fringes and represent a significant percentage of buyers of suburban tract housing.

In this environment, how can you define and recognize New Urbanism? CNU needs to work on authenticity of place, said Zimmerman. Urbanity was emblazoned as decay in the American psyche after the riots of the 60s; now, the suburbs have a similar stigma.

The basic components of housing value are size, quality, and location. You can slice lots in numerous ways to respond to market demand. Housing preference is harder to identify than neighborhood preference so a necessary question becomes: “How do we help the buyer identify what they want?” Asking when and where the millennials will start buying homes amplifies the question.

Rent is getting expensive, but millennials as a generation tend to prefer the maintenance-light option of renting. When this younger generation starts having children of its own, it is important for the urban centers to adapt to attract and retain the young families. At present, education is the issue that drives millennials with children out of cities; if education is improved, people will stay in the city.

Millennials are uniquely suited to conceive and address urban problems. CNU needs to create an agenda to retain millennials throughout all life stages. By focusing on downtown plans for the next 10-15 years, the city is poised to retain its current residents and entice new ones. Urbanists should mount a two-pronged program to: 1) kill the subdivision; and 2) renew focus on city-centers. Access to transit, schools, and amenities must be prioritized. The city has to be reinvented because it is now, more than ever, a place for innovation and vibrancy. People who are moving in are changing the city for the better, but they are moving into ill-suited buildings.

NU Council Discussion: CNU, City-Builder or Sprawl Retrofit?

CNU has always focused on the City, but suburban repair is now where the help is really needed. Sprawl retrofit is an important undertaking. CNU has some distance to travel to look towards the younger family. In terms of the work CNU can do, retrofitting a suburban community is work CNU is actively engaged in, introducing urbanity into the suburban framework.

Ellen Dunham-Jones on Sprawl Retrofit

Ellen Dunham-Jones addressed the problem of sprawl by suggesting suburbs be turned into models of sustainability through individual incremental projects. Most sprawl retrofit projects make suburbia more resilient, but Dunham-Jones asks if this is enough. Small increments work great when walkable infrastructure is already in place, but the biggest challenge is to get the street network into place around existing development. There is a rapidly increasing number of large-scale corridor retrofits underway, but it is still difficult to assess their scalability. The first generation of retrofits looks like an urban/suburban hybrid. Now the problem becomes an incremental increase of infrastructure to achieve an economy of scale.

Dunham-Jones suggests three strategies for retrofit: re-inhabitation by creating inexpensive space for community-based uses; re-greening by salvaging ecosystems, sequestering carbon, and finding more local sources of food and energy; and redevelopment by urbanizing and placemaking in context. If there is a market in which no development is on the horizon, there should still be a framework for implementing the strategies that allow for building out when the market recovers.

The one way to understand urban morphologies is to look at the "tissues of a place" by developing a “Retrofittability Index.” By creating manuals and websites outlining how to retrofit, the new urbanist ideals become more accessible to communities-at-large.

Challenges to these initiatives include improving the architectural quality and design of “instant urbanism,” enlivening public spaces by means other than retail, and dealing with zombie subdivisions and PVC farms. These obstacles are surmountable with the right tools. More research on financial performance, health, and environmental impacts, coupled with community outreach and policy change, can make incremental redevelopment increasingly widespread.

NU Council Discussion: Connect. Engage. Vitalize.

In the conversation after the presentation, connectivity was brought up as the main issue. Introducing urbanity into a suburban location is a good idea, but there is serious kickback when parking is threatened. It is possible to bring the ambiance of urbanity to new locations for the millennials who want it, but it is difficult to predict how these changes will affect property values. In addition, the U.S. is already over-retailed. There must be other ways to engage public spaces where retail is not the main social connector. Tactical Urbanism 1.0 needs to be a modular and evolving work.

CNU may own retrofitting suburbia, but the models need to focus on more than 60-year-old mistakes. People in urban places want urbanism; that fight has been won. Now is the time to take the momentum behind cities' growth and make urbanism attractive to people from suburbs.

Another area of focus should be directed towards old, small towns. There are thousands of them with no jobs and no industry, struggling to survive. It is possible to get professionals like CPAs, seamstresses, anyone that can work from home, to form a network of cottage industries. These are strategies that can be very feasible in the current economy if zoning structures are rethought. But first, there must be an established and proven framework for progress.

CNU CEO & President John Norquist refocused the debate: "Let's be careful where we are going to concentrate our efforts; urbanism means different things to different people. We're not going to write off Evansville – about ½ of America is suburbia. Here’s a chance for people to think about urbanism. Sprawl Retrofit is a portal to enter and learn more about urbanism."

Andres Duany on Hampstead

Andres Duany focused on the function of retail in the Hampstead, a community his firm designed on a greenfield site in East Montgomery. Retail as a social condenser is a stated belief; Duany asks what else can play that role. Developers in Hampstead focused on creating a place in which they would want to live. Dwellings there are radically different - space and waste are compacted. In Montgomery, there is a stigma associated with the “small-ening” of the house. A developer must address these preconceptions. Furthermore, bigger and still inexpensive lots are being sold around Hampstead. The recession has left, "the large units so cheap that it is irrational to buy the well-designed stuff." In Hampstead, CNU is working to turn this perception around.

Duany stressed that the most permanent thing planners draw is the street network, not the home. One must design and build the street network intact to allow for NU principles.

A Case Study: The Conversion the A&P Lofts

The A&P Lofts built in the Old Cloverdale section of Montgomery were built in 2005-2006, and accommodated people trying to get away from downtown and shipping areas. The original structure was developed in the late 1800s and became the A&P market, which finally closed in the 1980s. The one-story development transformed the market alongside a neighborhood of art galleries, a gas station, and a restaurant – all in a tiny one-block-area Main Street community.

The transition has been tricky, with market forces colliding on the CNU Charter Award-winning project. Adjacent to mixed-use area of the A&P lofts is a development of detached single-family units. A few of the houses were sold, but when the demand for rental became apparent, the project shifted into leasing. In full, the commercial units maintain a 95% occupancy rate, but the residential side of both the lofts and the detached housing has been struggling with purchase prices still dropping.

A&P Lofts, Old Cloverdale, Montgomery, AL

A&P Lofts, Old Cloverdale, Montgomery, AL

Nathan Norris on The Waters

Nathan Norris presented on the Waters Development located in the sprawling outskirts of Montgomery. The development process saw many challenges and ultimately led to many failures in implementing new urbanist ideals. From the outset, owners and developers of the project lived far outside of the city and could not understand why other people may not want to live as far out. The owners actually had no basis for the location of the development and developers did not understand the mixed-use dynamic. The 200-acre lake “would’ve been built for cows in all that you needed to do was put in a berm.” The failures in execution abounded: there were no front entrances for residences, two-story residential suites were maintained instead of the more appropriate single-story units, there was no dignified entrance, the price point was wrong, there was never agreement on what the landscape should look like, the hydrology was incorrectly predicted, planting strips were too narrow, and the lots were too shallow. The result? Good intentions, but loan defaults and a whole lot of mud.

Scott Polikov on Harnessing Form-Based Codes as Development and Investment Tool

Texas planner Scott Polikov presented an aggressive big picture proposition: leverage a form-based code as the equivalent of a master developer and guarantor of long-term predictability in an otherwise unpredictable economic environment. Presenting an example of a project in Roanoke, Texas, Polikov demonstrated the potential for long-term returns on mixed-use development guided by FBCs. By promoting small-scale, incremental development, a community can take advantage of existing successes adjacent to new development. The risk of investment is lower because it is spread over many uses; the FBC provides predictability and market analytics. This is a return to the traditional model of investing in infrastructure based on the performance of the surrounding real estate. Rail systems can also be used as an excuse to reinvent urbanism throughout the entire transect. Rail will not drive all development, but it will spark talk about development in neighborhood-level increments.

Form-based code can act as land bank mechanism when feedback is received on a block-by-block basis. Polikov stresses, “You have to be talking about the numbers at the onset, not the design. Politicians don't care to see [the project] through, as they will be gone by time development comes through. They want numbers.”

Banks care about FBCs too, due to better returns and predictability. Development agreement and fiscal arrangement are essential to keeping check on city council changes. Polikov suggests a checklist for underwriters and cities for FBC application.

John Norquist Keynote Address on Live/Work/Walk: Removing Obstacles to Investment

The American dream of owning a home, whether rich or not, was created when FDR signed the bill creating the Federal Housing Administration. From the outset, the bill made the banking industry nervous. Sen. Walter George, Chairman of Banking Committee, insisted the FHA have a number of restrictions to prevent the federal government from taking over the banking industry. Restrictions included the allotment of money to residential developments, which eventually evolved into a percentage cap on commercial uses.

The first ten years of the FHA allowed for continued mixed-use, which found financing because there was so much inertia behind the previous policy. Banks looked at the mixing of uses as a way to mitigate risk. Since then, single-use one-story building has predominated.

The only way to deal with this problem within the current framework is an "exceptions process," but there are a lot of developers who want to operate in the marketplace without having to contend with additional layers of bureaucracy to build and deliver mixed-use product. After 78 years of the financing regulations in place, private banks now treat mixed-use as an automatic risk. Norquist noted that of the government hadn't influenced thinking to a point where mixed-use was marginalized, the effect of sprawl would be minimized. Now, even if restrictions were to be lifted, banks need to re-learn mixed-use lending.

CNU is now pushing the Department of Housing and Urban Development and Government-Sponsored Enterprises to raise mixed-use limits to 45%. It would still be tough for developers to build, but it's a step in the right direction. CNU needs to be working in tandem with the agencies, not just attacking Fannie, Freddie and other federal agencies. CNU has a record of inserting itself into the system to get things accomplished though. By getting rid of the functional classification system and using ITE, CNU inserts itself into the world of DoTs. Now is the time to do the same for financing so the market can deliver good affordable housing and the access to urbanism that people increasingly demand.

NU Council Discussion: Eliza Harris on NextGen

Eliza Harris kicked off this discussion regarding the role of NextGen within CNU. Harris said that most members of NextGen eagerly support CNU, but some feel that the organization has stalled. There is balance to be had between youth culture and authority and, right now, it seems the organization seems to be focusing too much on what NextGen may do next.

To some extent, things have gotten more complicated, because there is no single direction in which CNU should go; the organization needs to move in a multiple directions on multiple levels. More focus should be put upon critiquing and fleshing out “incremental urbanism.” Within Tactical Urbanism, there is a dichotomy between tactics and strategy. Strategy entails getting people excited about urbanism.

NextGen thinks of the next increment; whereas the older people are thinking of the next lot or block. Action vs. product. CNU should seize the opportunity to redefine the underlying structure and then create consistency in projects based on that underlying structure. There ought to be tension between NextGen and the broader CNU to push urbanism forward. New generations cannot be allowed to ossify. The tension is needed in order to win social justice, social economy, and environmental harmony.