Lessons from travel: Het Schip

I love to travel. Every trip widens my bandwidth, challenges my orthodoxy, introduces ingenious solutions to seemingly unsurmountable problems, and exposes me to the choices people make in living their lives as individuals and as a community.

My recent trip to the Netherlands provided several such lessons. Most impressive was the insight of the merchant class of the early 1900s, and their will to build beautiful, affordable housing for the working class. A model that should inspire and be emulated by today’s wealthy class — the 1 percent of society that controls 90 percent of the global economy.

A second personal discovery was learning about the architect Michel de Klerk and his aspiration to express beauty through the art of architecture, on the exterior of a building for the public to enjoy, rather than limiting the placement of art objects to within a building. The outcome of this investigation and the built body of work came to define what became known in architecture as the Amsterdam School.

A third lesson was the reinforcement of the idea that despite first impressions, colored by one’s own aesthetic predilections, we sometimes have to dig deeper to extract the embodied knowledge buried in the history of a building, block, or town.

Patronage

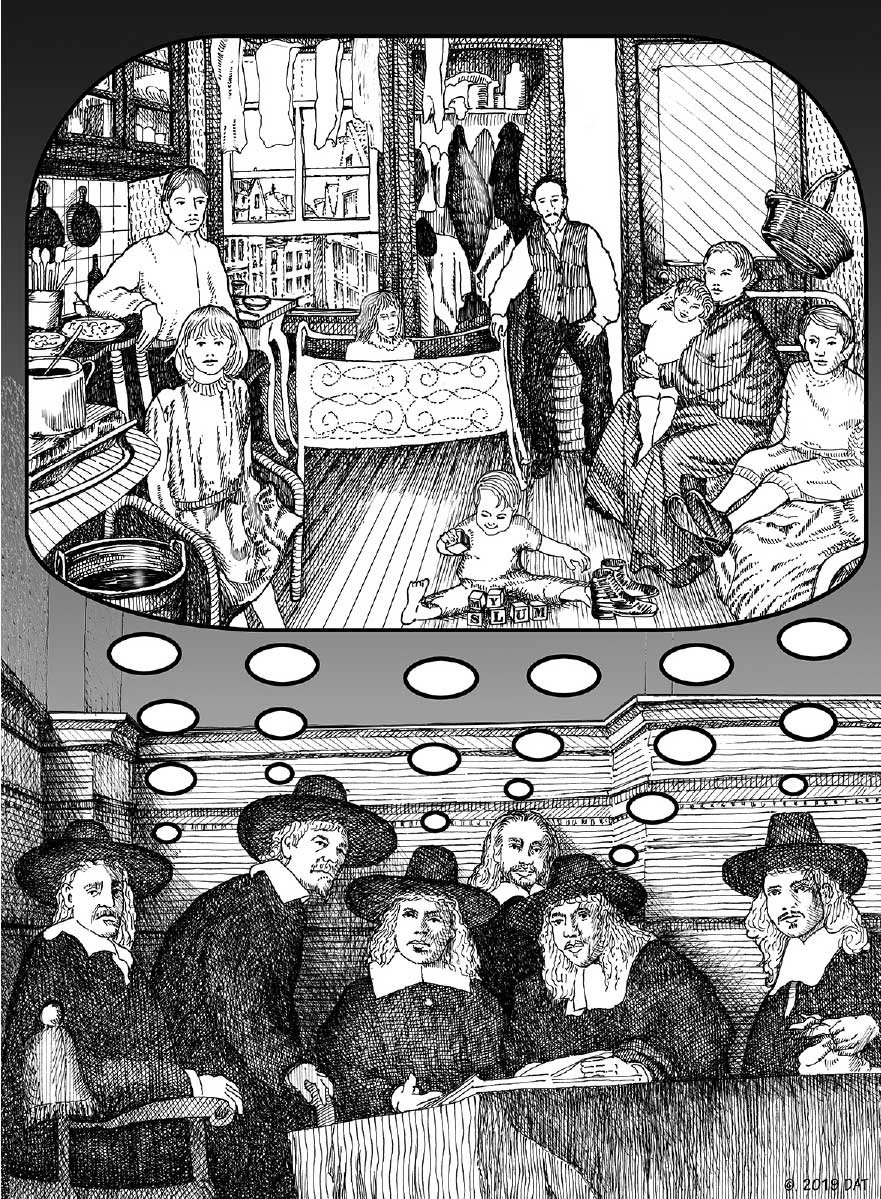

In 1909 a group of men gathered to discuss a deeply troubling condition that plagued their city, Amsterdam. The economic success of the city had caused the population to grow at an alarming rate, resulting in horrendous living conditions for the working class. This was unacceptable to these concerned merchants. Their city was prospering on the backs of the working class, and there was a large disparity between the haves and have-nots. The men decided to found an association to build good quality and affordable housing for the very low- and low-income population. They believed that the true measure of a city could only be judged by the treatment of residents who were less fortunate, impaired, insecure, and defenseless. A workforce treated with respect and dignity, exposed to beauty, blessed with peace of mind and contentment would eventually translate to greater productivity at work and a reduction in crime within the city. Furthermore, the city could not thrive without every citizen’s contribution and every resident was entitled to have a safe home to return to after a hard day’s work. The association was called Eigen Haard which translates to “one’s own hearth.”

The formation of Eigen Haard in 1909, and subsequent accomplishments, inspired several factory owners and faith-based organizations to undertake building affordable housing for their constituencies. Eigen Haard’s most famous project was Het Schip, or The Ship, a housing block on a triangular site on Zaanstraat in west Amsterdam, designed by the compassionate architect Michel de Klerk, who stated that “Nothing is too good for the worker who has had to do without beauty for so very long.”

Architect

Michel de Klerk had taken a critical view of the widely admired architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage, who he claimed did not grasp the possibilities of the time. De Klerk acknowledged that several of Berlage’s building projects had professionalized the building trades. He too shared Berlage’s love for traditional craftsmanship, however he was critical of Berlage’s emphasis on technical and utilitarian aspects of architecture. De Klerk wished to derive beauty from the art and craft of building.

Michel de Klerk was born in 1884, and experienced the squalor of working class housing while growing up in a poor Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. His early passion for drawing was noticed by architect Eduard Cuypers who offered him an apprenticeship when he was only thirteen years of age. Working in the office, taking evening classes at trade schools, learning to draw from live models, and supervising construction works, he groomed his skills to become an accomplished artist, furniture designer and architect. He collaborated with many architects on several projects and left his indelible mark on every design by highlighting craft in the finished work. His reputation grew and in 1913 he was commissioned to design the first of several affordable housing projects.

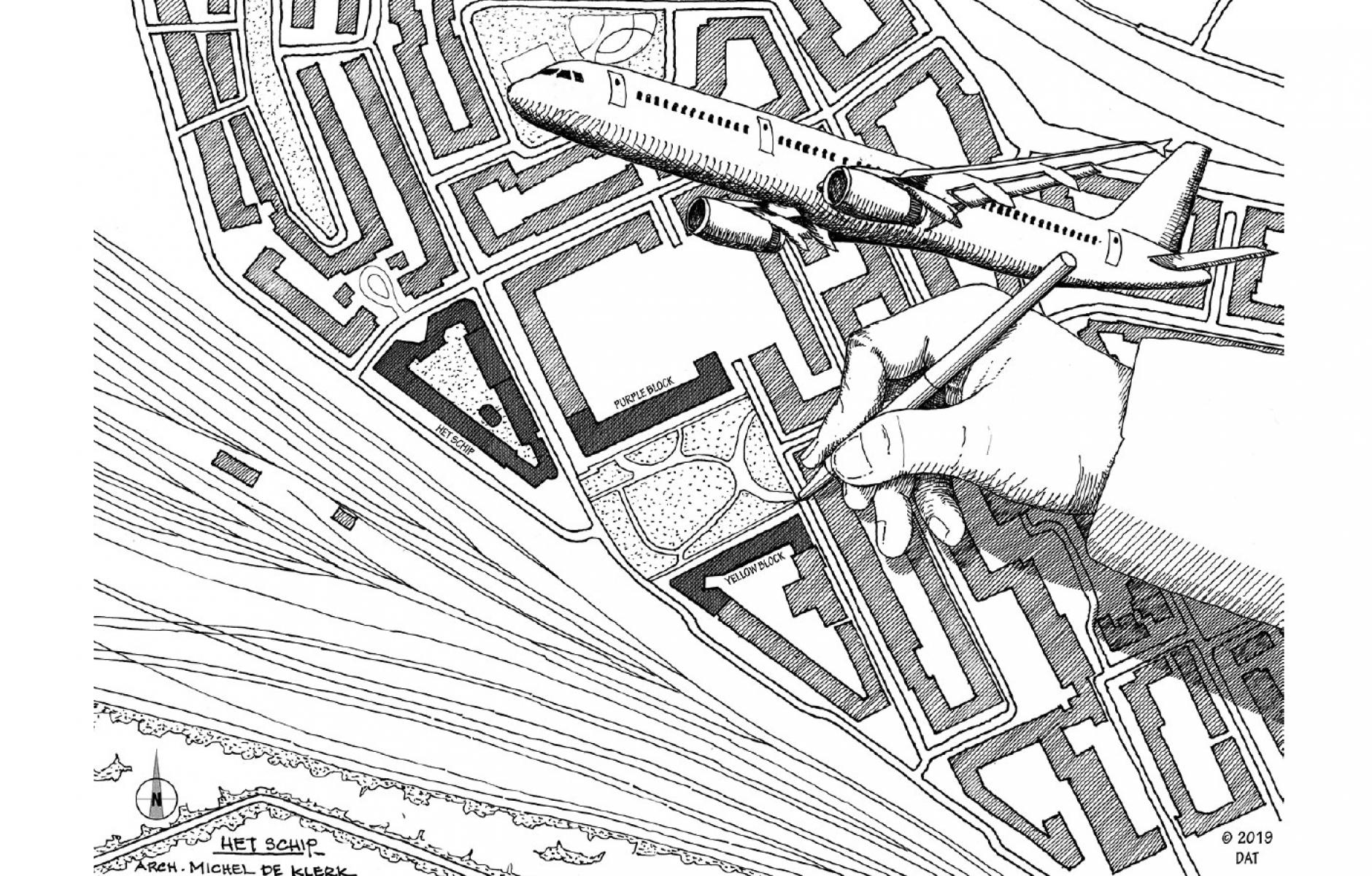

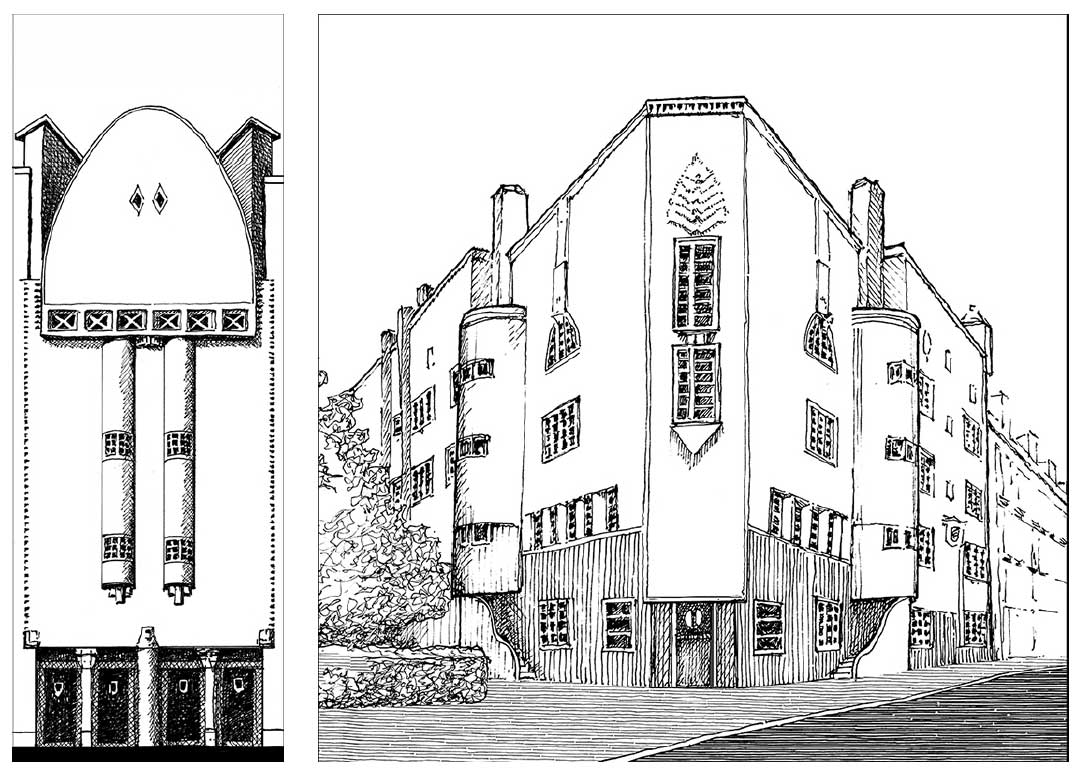

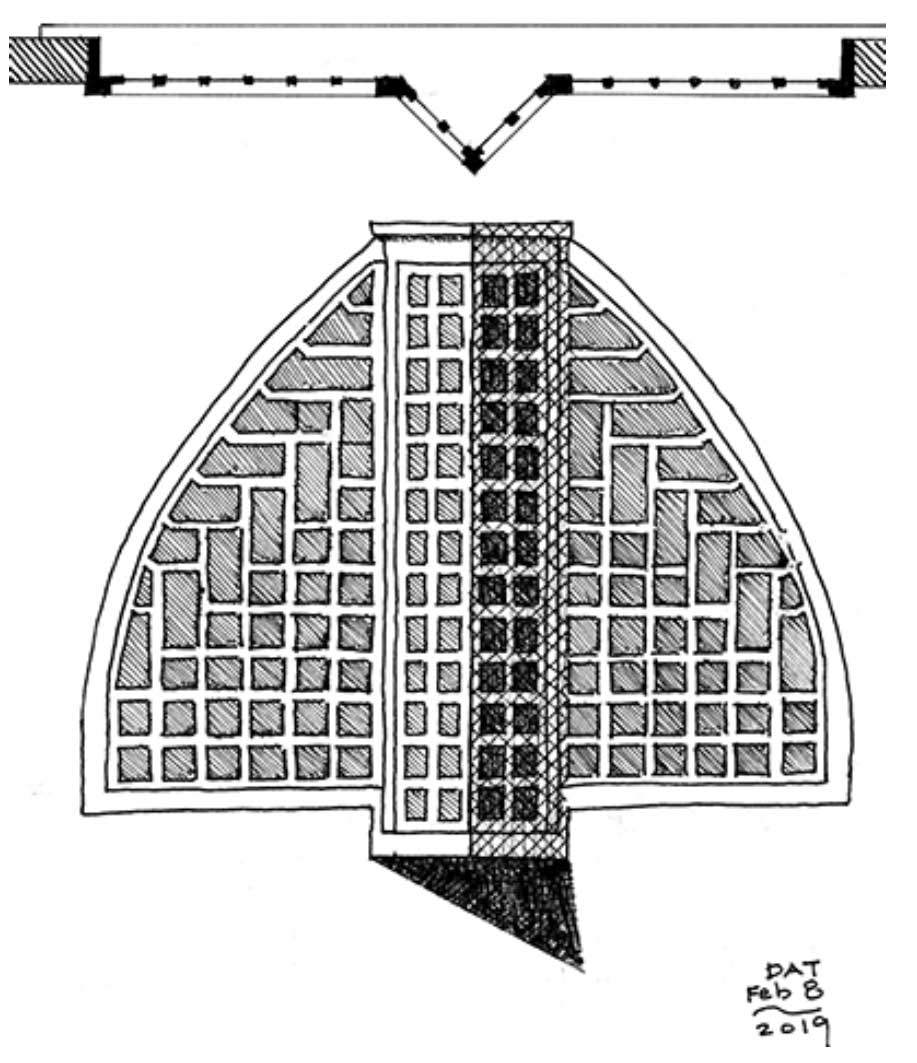

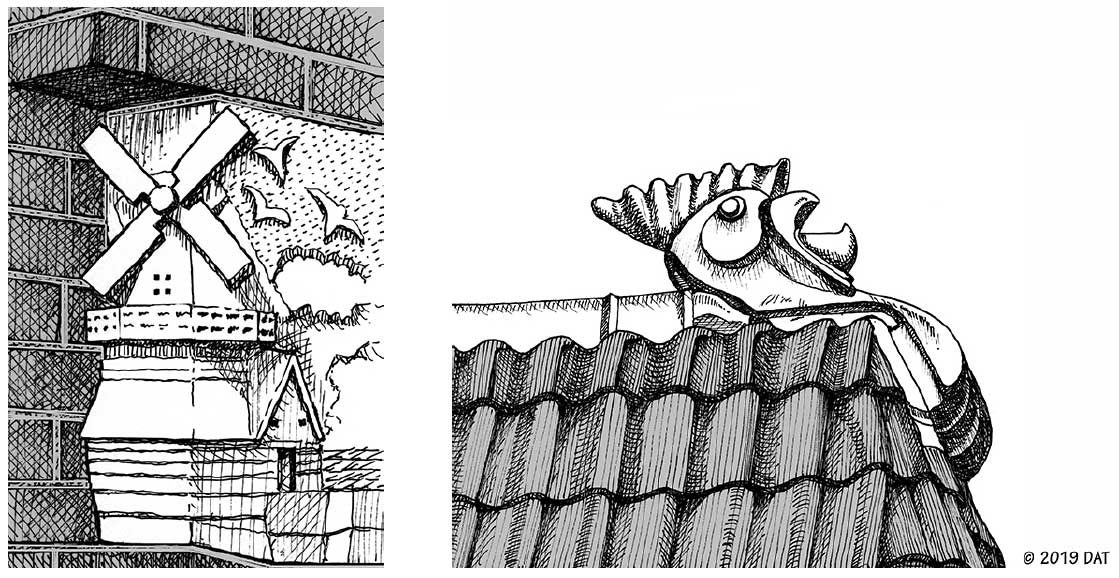

Prior to designing The Ship for the Eigen Haard association, de Klerk had completed two housing blocks facing Spaarndammerplantsoen, a park across the street from the Het Schip site. The first ‘Purple’ Block was completed in 1914 (see plan at top) and was identifiable by its anthropomorphic parabolic-shaped, gabled stair towers, and diversity of materials on the facade. The entry doors were abundantly decorated making crossing the threshold a pleasurable experience. Iconographic artwork was integrated into the structural components of the building, depicting themes of windmills and haystacks that would be familiar to the residents. At the corner of the block he integrated into the brickwork a terracotta gnome wearing wooden clogs, that depicts a playful side of the architect. Both corners of the housing block have retail on the street level, with large window sills to encourage pedestrians to rest and chat. The critics considered the building intriguing due to its unexpected elements and color, creating a sense of anticipation and a desire to explore further.

On completion of the ‘Purple’ Block, Michel de Klerk began work on the ‘Yellow’ Block directly across the park. The project experienced setbacks due to World War One, as the builder could not meet his obligations. The municipality asked the Eigen Haard association to complete the project and continue to work with de Klerk — who made the necessary changes required by the association. The two facades opposite each other facing the park have an obvious kinship, however the yellow brick and red roof tiles make the second building more exuberant. Elements from the natural world are featured in the stonework, and the variety of brick bond patterns display a remarkable sense of detailing. The project was heralded as exemplary in achieving a harmonious relationship between building and context and in attaining unity between various facades.

Het Schip

In 1918 while work was being completed on the ‘Yellow’ Block — Eigen Haard commissioned Michel de Klerk to design a housing block on a two-acre triangular site whose tip was across the street from the south side of the park. As per Eigen Haard’s mandate, the units were larger than the prescribed minimums in order to accommodate families. De Klerk organized 102 unique apartments on the site with twelve different street entrances into the units. Each entry is playfully different in form and identified by De Klerk-designed numerals embossed into the canopies. There is a myriad of white-framed orthogonal and trapezoidal window types that animate the facades. Eighteen different floor plan configurations make for diversity within the single residential block. Most units consist of two bedrooms, bathroom, living room, and larger than normal kitchens to permit dining in the kitchen.

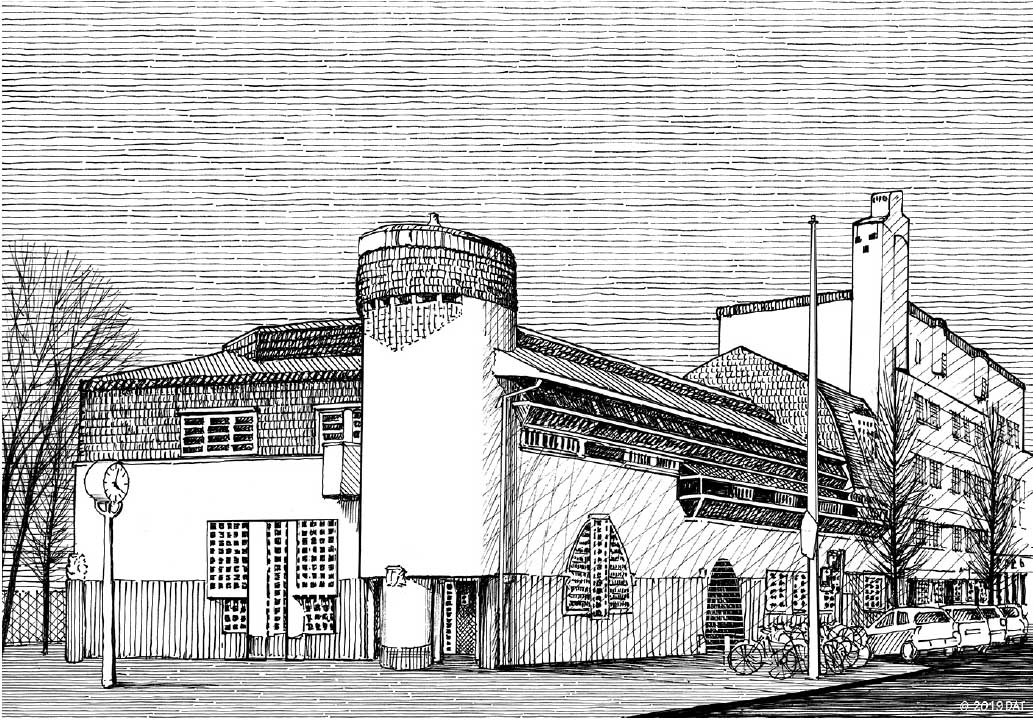

A two-story school building had been completed on the northern edge of the site in 1915. Given its recent construction it was prudent to incorporate it into the composition. The new five-story building engulfs the school facade and spans over the existing building. De Klerk designed each elevation to respond to the context facing the facades. The north and south facades are predominantly horizontal compositions, with the north facade incorporating the existing school facade.

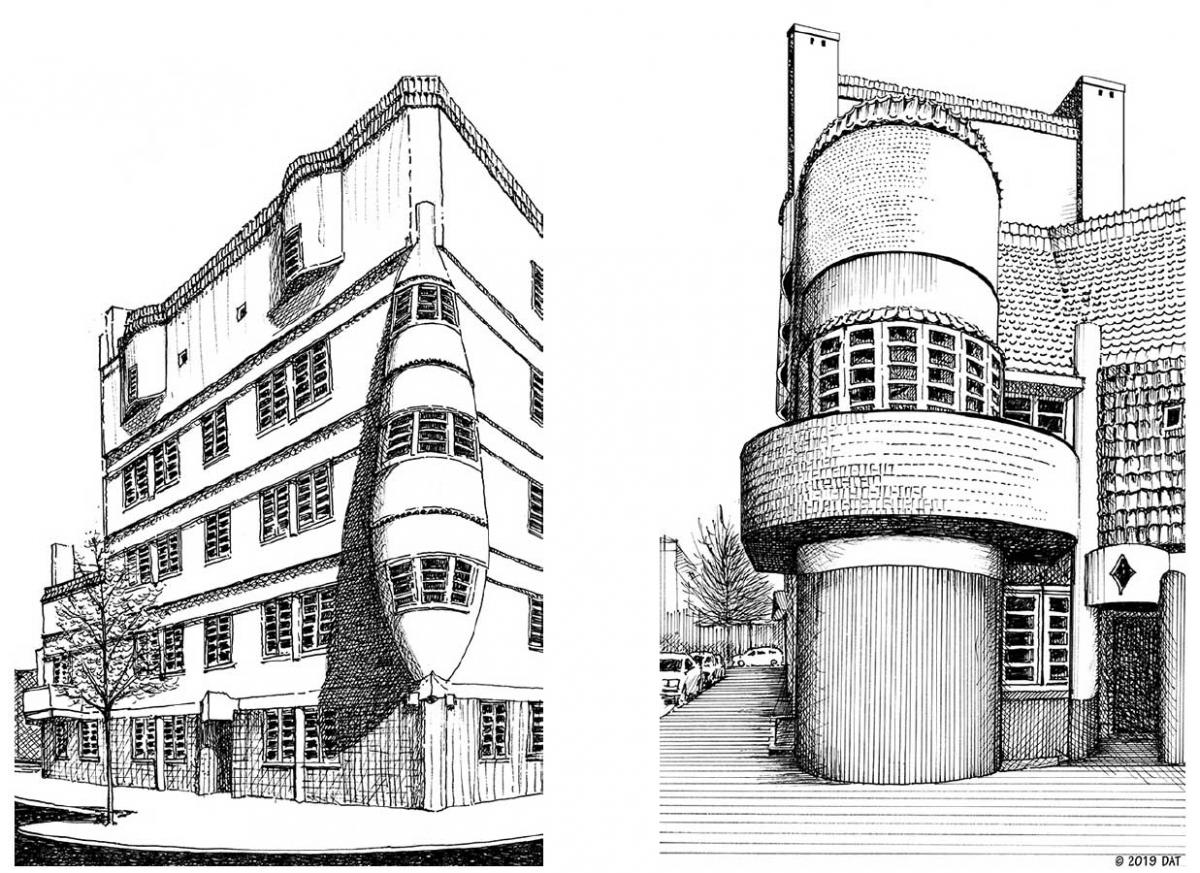

There are several plane changes on the two primary facades that create shadow lines emphasizing the horizontal. The Zaanstraat facade faces the railroad tracks to the south and the horizontal bands are framed by a stair tower on the east and interrupted by a protruding ‘cigar’ bay on the west corner. This extravagant beautifully detailed corner element produces little significant spatial benefit to the three interior floors that it engages. However, the visibility of this element from the commuter railroad created much talk about the lavish expenditure afforded to worker housing by Eigen Haard. Along with a spire soaring above the roof, which could also be seen from the railroad, the project was easy to recognize and word quickly spread about the association’s mission to provide affordable and beautiful housing for the working class.

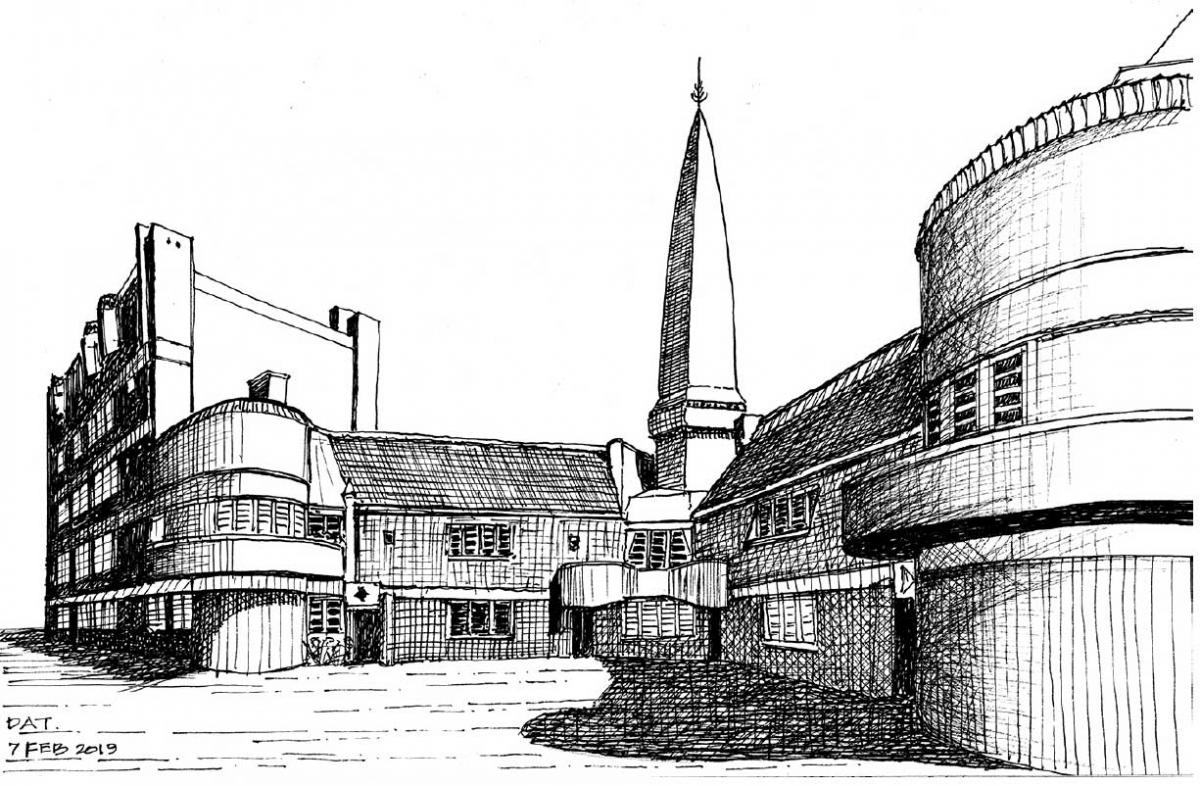

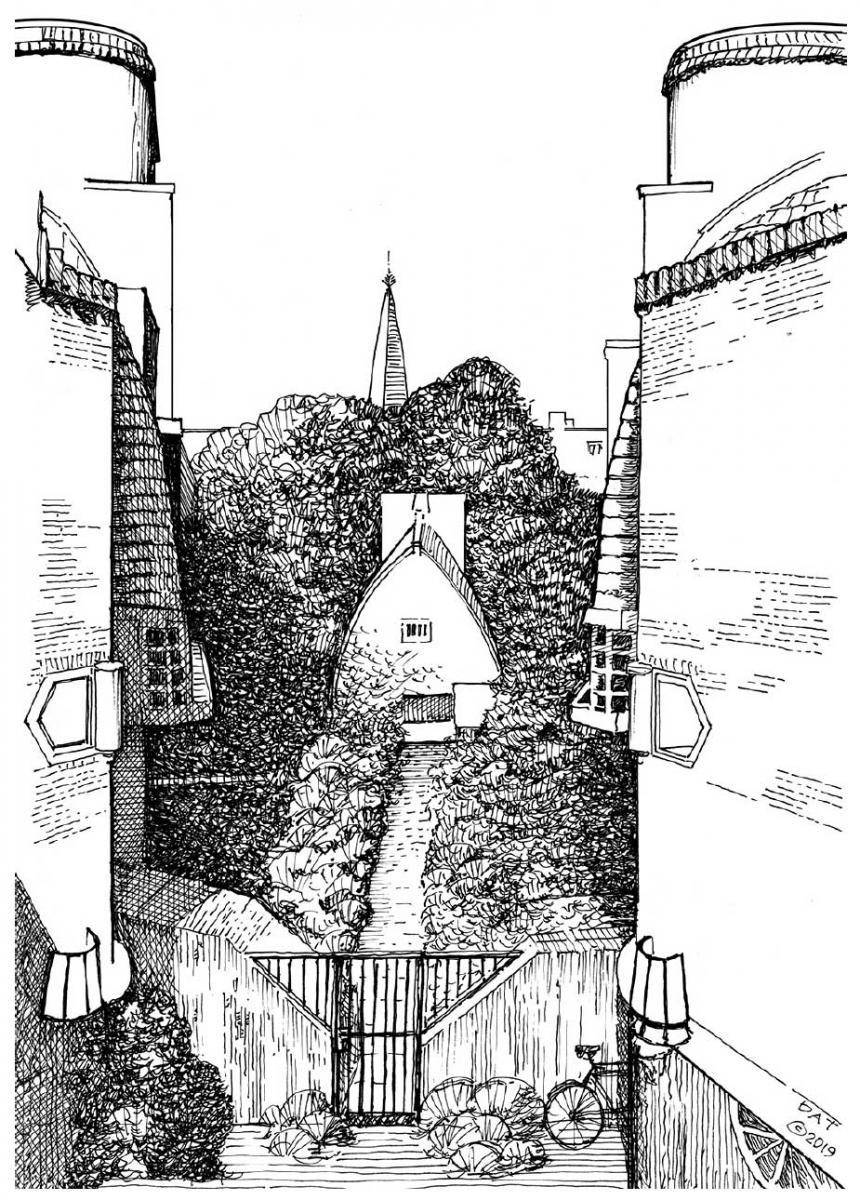

On the west side of the building facade a small urban square is formed between where the north and south facades turn the corners. Two protruding cylindrical forms mark the corners and mediate the scale, softening the entry into this space. Two-story bands sprout the monumental spire on axis with square. The spire is crowned by a wrought iron tree of life sculpture. This ancient symbol, common to many cultures, signifies that something is growing, indeed blooming within the building. The motive for the spire was emotional as it serves no functional purpose, yet the spire memorably landmarks the place and responds to the entry court of the housing block across Hembrugstraat.

At the eastern apex of the triangular site a two-story post office dominates the corner. Approaching the building from the east on Zaanstraat, one sees the post office with its oval tower looming in the middle of the thoroughfare and serving as a beacon. It is evocative of a steam locomotive or the bow of a ship. Also, on the exterior of the post office, rectangular gable stones, reference stamps, post-horns, lighting bolts, and greyhounds symbolizing the speed of the postal service.

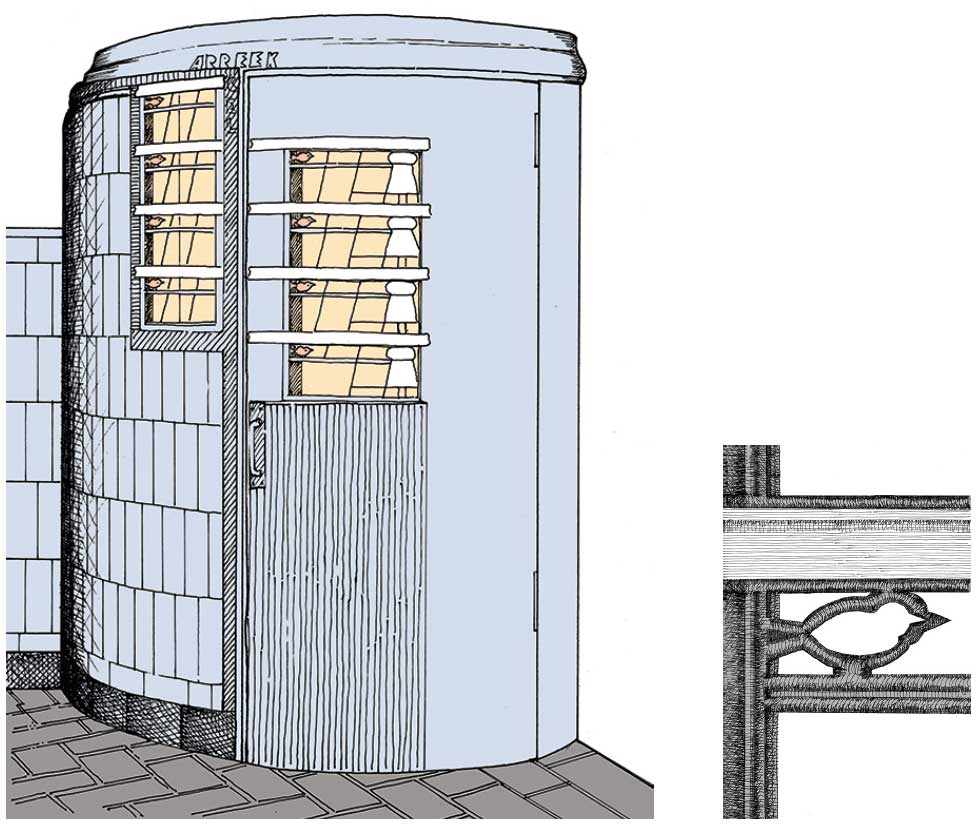

In the interior, the post office had a single phone booth where long distance calls could be placed. De Klerk designed a bright blue ceramic-tiled phone booth enclosure with a metal door. The door frame with white horizontal window mullions suggests a telephone pole, and stained-glass iconography depicting birds on a wire support this allusion.

Another function of the post office was to provide a safe place for workers to collect their weekly wages. At the time, it was common practice for factory workers to receive their wages at drinking establishments. These bars were owned by the factory proprietors and they encouraged workers to spend their earnings at the pub prior to returning home. To counter this devious practice it was legislated that workers must receive their earnings at the post office.

Behind the post office is a small tranquil inner court which leads to a larger garden courtyard for use by the residents. The inner court is accessed from the street through a deep parabolic archway. Ten units are entered from this inner court, with some of their bay windows overhanging the garden. Inside the courtyard is a multifunctioning meeting hall with a small footprint, but spatially grand with a curved gable roof form with exposed timber roof framing. Tenants pay a membership fee to the association making them co-owners with duties and rights as agreed in the tenancy agreement. The meeting hall has a small borrowing library for residents, and is used for association meetings, resident activities, educational classes and training. In the past, the association would buy fuel, potatoes, and other necessities in bulk, store them in the meeting hall, and distribute the items to the residents.

True to his belief to instill beauty into the daily lives of the working class, de Klerk infused symbolic relief sculptures into the walls and structural elements, exposed fine craftsmanship and detailing, attempted to uplift the human spirit with art, and introduced a whimsical hide-and-seek curiosity to the daily promenade through the building. When completed in 1920, Het Schip was criticized for its cost overruns, yet greatly admired by residents and the housing council. Three years later, Michel de Klerk’s illustrious career ended with to his sudden death on his 39th birthday, November 24, 1923. A year later, Amsterdam hosted the International Congress for Housing and City Planning and delegates were taken on a bus tour to see his masterpiece, The Ship.

Although de Klerk’s architectural gem is unknown to most architects, the Dutch recognize and value his work. Het Schip has recently been painstakingly restored and the former school building artfully repurposed as a museum to display significant art and architecture of the period. The work of Antonio Gaudi, a contemporary of de Klerk, was recently on exhibition in the museum. It is important to note that while de Klerk’s personal predilection was to express the art of architecture, his humility allowed him to respect the urban and cultural context of his building sites. His life's work places Michel de Klerk in the pantheon of early 20th century architectural luminaries.

Last Word

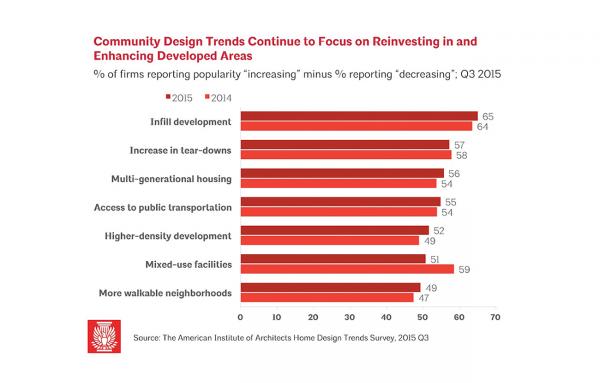

The income disparity among city dwellers that led to the formation of associations such as Eigen Haard is a lesson relevant in today’s world. Cities continue to be the most dexterous and resource-efficient form of human habitation. Globally thriving cities have an abundance of employment opportunities and they attract a workforce desperate to earn a living. Slums are a consequence of mass migration to these robust job centers. As a consequence, they are havens for substandard housing, unhealthy living conditions, and unsafe places to nurture the next generation. For the sake of humanity, it is incumbent on the wealthy class to help build beautiful and sustainable housing for the burgeoning urban population, so that every citizen can contribute to the welfare of their city, and have a safe home to return to after a hard day’s work.

Illustrations by Dhiru Thadani.