A comprehensive guide to buildings in walkable neighborhoods

When I prepare to review a book, I highlight key passages. But I couldn’t bring myself to mark up the pages of Increments of Neighborhood: A Compendium of Built Types for Walkable and Vibrant Communities. My highlighter hovered over the first few pages, until—nah—I just put it away. There is plenty of interesting material, but I want my copy to stay clean.

Brian O’Looney worked on Increments of Neighborhood for 15 years while part of the teams designing new urban projects for Torti Gallas + Partners and David Schwarz Architects—a number of them, like the Columbia Heights Redevelopment and the Social Safeway, Charter Award winners—and it is one of the most remarkable textbooks produced by new urbanists. I hope that the current coronavirus crisis does not draw attention from this book, which should be on the shelf of every urban designer, planner, architect, and developer (small or large) working to build urban places. This book should definitely be available at every charrette.

And I don’t say that because I think O’Looney should be rewarded for a job well done. The book is just plain good. I’ve been writing about urbanism for 25 years and have studied the details of more new urban designs and developments than most practitioners, and wrote or corwrote four editions of New Urbanism: Best Practices Guide. I can flip to any page of Increments of Neighborhood and learn something. There are some books that help you to understand the built environment better, and this is one of them.

This is a hard book to review. It advances some arguments, but that’s not the main purpose. It’s not a text that you read from beginning to end. It’s a book that you absorb, slowly. That building over there? It’s on the edge of downtown, or on Main Street, or a residential street. You basically know how it works, or think you know, but here’s how it really works. Here’s the category that it falls into, the purpose it serves, the construction materials, the costs, the stairs, the hallways and floor layouts, how the parking works. Here’s how you recognize this type from the outside. And here’s the critical difference between this building and another that looks nearly the same, but serves a different purpose. And here’s how it fits into a walkable neighborhood.

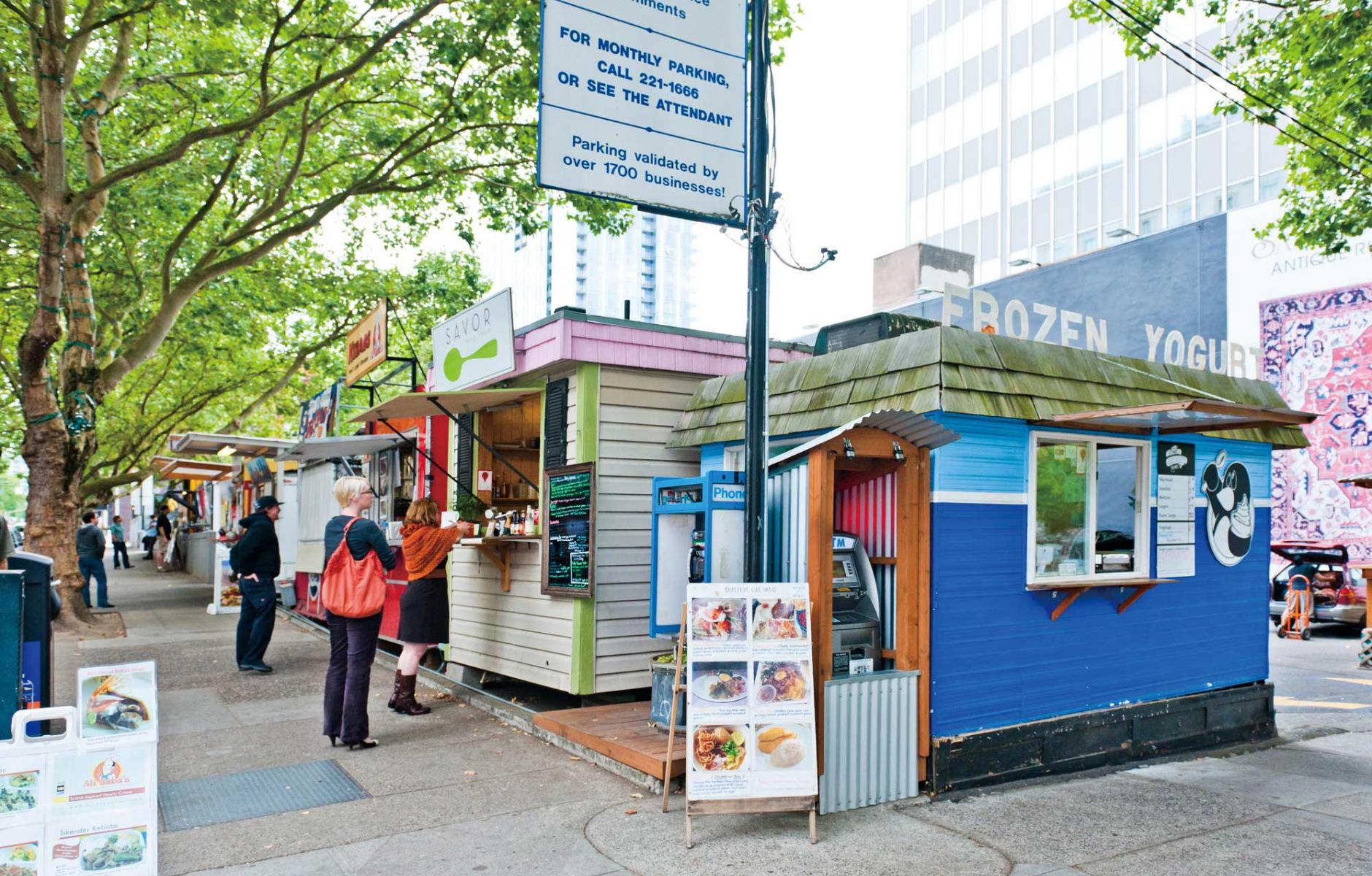

The last point is crucial, and that’s what sets this book apart from any other book on architectural typology. This book covers types that are useful for any purpose in creating all kinds of mixed-use neighborhoods—downtown, general urban, transit-oriented, walkable districts. For every type, there is a small item called “missed opportunity” that highlights what happens when you take the typical sprawl approach. This is a toolbox for the New Urbanism that is designed to pack as much information as possible into a limited space—and that’s useful, too. It’s fairly heavy and durable, and you are going to want to lug it on the plane to design sessions.

All about type

The author identifies 24 single-family types, and all of them can fit into walkable neighborhoods—there are no front-loaded houses or McMansions. There are dozens of missing middle types, including 18 townhouses and 11 “stacked unit” types. Many larger buildings are included that would fit into a walkable urban center or downtown—including public buildings like police station, hospital, arena, stadium, and so on. Each type occupies two facing 8.5-by-11-inch pages (expanded to four in a few cases). Each spread has a table, text, and 10-15 images, including plans, diagrams, and photos. There are thousands of images in Increments of Neighborhood, which would ordinarily be overwhelming. Because of the way the book is organized, the number of images feels right.

Do you know the difference between 12-foot, 14-foot, 16-foot, 18-foot, and 20-foot-wide townhouses? Besides the fact that one is two feet wider than the next? There’s more to it than that—such as how each type deals with utilities, parking, outdoor space, layout—and you really should have access to this information if you are a town or city planner, writing or administering a form-based code. For $50 (price that I found discounted from the $80 list), now you know. That’s a bargain. I’m telling you.

Although this is mostly an architectural typology book, O’Looney includes an excellent section on mobility and access types, ranging from pedestrian-oriented street furniture to heavy metro rail—subways and elevated systems. These, like buildings, are crucial objects in walkable neighborhoods. This section alone is worth having Increments of Neighborhood. It also includes the only section of the book that may be controversial—14 parking types are explained. Some readers will ask: Why all of this attention on parking? Isn’t the point of urbanism to avoid so much parking?

O’Looney criticizes parking requirements in land-use codes, calling them “legislated emptiness.” This point is reinforced through images and text. But the need for parking is not going away—although it will likely be reduced in many places with autonomous vehicles. To the extent that parking is needed in the decades to come, these types are highly valuable tools to right-size parking and reduce its impact. Personally, I find it fascinating to understand and compare, say, parking stackers/lifts, elevator garage parking, and robotic parking machines—the distinctions of which I never knew before. These 14 types offer myriad ways of fitting parking into small urban spaces.

Why type?

At the very beginning of the book, O’Looney includes an illuminating definition of type that came from a discussion with his neighbor, architect Mike Watkins. “He took a white ceramic coffee mug and a familiar mass-produced red plastic party cup and put them side-by-side, and asked me: Which one is for cold liquids? He then relayed a definition of type attributed to his former boss, Andres Duany: ‘Form determined by function, and confirmed by culture.’ ”

Why is a wine glass a wine glass? Because millions of users over centuries have determined that it is the best vessel type to drink wine.

Architectural type is similar. It has to pass the test of being useful to designers, developers, and the purchasers and residents of buildings.

Most of the buildings in the book are not sponsored by patrons. They comprise private sector buildings in cities and towns—although some of the examples are subsidized affordable units or military housing. Economy is at the heart of all of these types. “This book focuses on commodified real estate products in the service of good urbanism, great places, and wonderful communities,” explains O’Looney. Even the public buildings offer a “vision of making great places with buildings produced within the bounds of an efficient, democratic, effectively competitive marketplace.”

And regulators have their say. When codes do not allow for types that meet market demands, they fail. “There are a number of well-meaning, but unworkable, form-based codes of walkable urbanism which unsuccessfully grapple with the more intensive end of density,” O’Looney writes. “Many of these look plausible, yet they often fail because required building types are too complex, too specific and/or too difficult to finance.”

Type, and associated regulations, can profoundly affect affordability. “It is not well known that one square foot of a downtown high-rise apartment costs twice as much ($160-$250) to construct as a wood house in the suburbs ($80-$105). On average, it costs $8,000 to build a bathroom, and $16,000 to build a kitchen for each unit of housing, but zoning laws in some jurisdictions also require two $35,000 underground parking spaces for the same unit.”

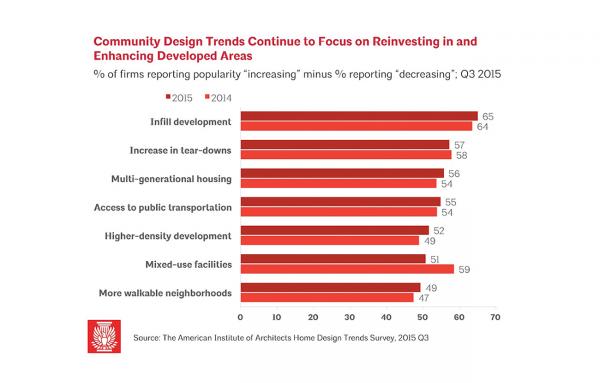

Eliminating the unnecessary parking requirements and using housing types that employ cost-effective construction, like various kinds of stacked flats “should be more widely embraced across North America because they are inexpensive to build, provide more housing options, and well-suited to small infill sites—reinvigorating our underutilized civic cores.”

When this coronavirus crisis is over, you are welcome to look at my copy Increments of Neighborhood. Just don’t mark it up. Better yet, buy one for yourself.

Increments of Neighborhood: A Compendium of Built Types for Walkable and Vibrant Communities, by Brian O'Looney, 2020, ORO Editions.