What comes after the highway?

It’s no secret that highway builders leveled vibrant communities to make way for many of the roads in our cities today. It’s also no secret that highway builders often targeted communities of color, who typically lacked the resources required to fight back. The disproportionate effects highway building had—and continues to have—on Black and brown Americans presents a compelling moral reason for Highways to Boulevards projects.

If Highways to Boulevards projects are to right historical wrongs, it’s imperative they provide healing for the communities most affected. CNU’s new Executive Director Rick Cole knows how important this is: "As a key part of America's reckoning with institutional racism, there is an urgent need to heal the raw wounds created by the bulldozers that cleared the way for urban freeways."

But as the New York Times’ Nadja Popovich and Vice’s Aaron Gordon point out, the demolition of these highways is the easy part; rebuilding and ensuring that the people who live around them benefit will take time and effort. To be successful, these projects need to be driven by and designed in partnership with the community members who have been burdened by the highways themselves.

Freeways Without Futures 2021 features several Highways to Boulevards projects that envision the removal of a highway as a first step in a more comprehensive reparative program. From Tulsa to New Orleans, Syracuse to Oakland–we recognize the following campaigns to get rid of the highways that continue to inflict damage on Black communities and identify the work required to reach repair, beyond removing the road:

Interstate 244, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Interstate 244 runs directly through Tulsa’s Greenwood district, the historic center of the city’s African American community once known famously as ‘Black Wall Street’. In 1942 (21 years after the Tulsa Race Massacre), Greenwood was home to 242 Black-owned businesses spread over 35 square blocks. The highway, built in 1965, reduced that number to only a handful, most situated on the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue, which local attorney E.L. Goodwin, Sr. had saved through negotiations.

Today, I-244 in Greenwood forms the northern part of a series of highways known as the Inner Dispersal Loop (IDL) that cordons off downtown from the rest of Tulsa. Parts of historic Black Wall Street remain in its shadow, including the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue (also known as Deep Greenwood) and a pair of churches (the Mt. Zion Baptist Church and Vernon AME Church) that were burned down during the race massacre and rebuilt afterward. Just north of the highway is the Greenwood Cultural Center, built in 1980 to celebrate the achievements of Black Wall Street residents and remember the tragedy of the race massacre.

These community assets could serve as the foundation for a revitalized Greenwood following the removal of the northern section of I-244 along the IDL. The concept is a nascent one, but the Tulsa Regional Chamber, Historic Greenwood District Main Street, and other local advocates think it is worth exploring. I-244 acts as a physical barrier between predominantly Black north Tulsa and historic Greenwood Avenue, as well as downtown to the south. By removing the highway and restoring street connections, north Tulsans would be able to more easily walk or bike downtown, and business owners in Deep Greenwood would benefit from increased traffic. New land would also be available to expand Deep Greenwood northward, where it is largely constrained by the presence of the highway.

Of course, the removal of I-244 alone won’t restore Black Wall Street and undo the damage inflicted on this community. But coordinated reparative programs, coupled with the highway’s removal, can support community efforts to build a new Black Wall Street. This includes programs to help develop new Black-owned businesses while boosting existing ones, leveraging the City’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund to create affordable homes within walking distance, and establishing a community land trust to rehabilitate vacant lots and abandoned houses in line with residents’ interests. It will take focused investments and intentional policies like these to rebuild an expanded Greenwood district that does justice to historic Black Wall Street, while also addressing displacement concerns.

Claiborne Expressway, New Orleans, Louisiana

When the bulldozers arrived on Claiborne Avenue in 1966, they did more than uproot the century-old oak trees that lined its park-like median; they destroyed a landmark central to the Tremé neighborhood’s Black community. Now, to remedy this wrong, the Claiborne Avenue Alliance has led a renewed effort to take down the expressway, reclaim this historic neutral ground for Tremé’s residents, and provide a pathway for community revitalization.

The Alliance’s plans seek to channel the benefits unlocked by taking down the expressway to serve the members of the current community. First and foremost, it advocates for the restoration of the median to its former state and restoring the lost tree canopy. This gathering space will serve as the backbone for a revitalized business corridor that brings goods and services back to the neighborhood. There is also the opportunity to create affordable housing through infill development and the rehabilitation of the existing homes that have fallen into disrepair.

All of this is underpinned by policies the city can adopt to protect current residents from being displaced by rising prices once the highway is removed. The early establishment of a community land trust to acquire available real estate and resell it at below market value to residents is a critical strategy to help renters (70 percent of the community as of the 2010 census) transition to home ownership and stay in the neighborhood. Additional strategies, such as incentive programs that assist residents with home maintenance and tax-freezing programs to relieve the escalating assessments already driven by short-term rentals, will help keep residents in place to enjoy the benefits of a restored Claiborne Avenue.

Interstate 81, Syracuse, New York

When it was first built over 60 years ago, I-81 valued the convenience and mobility of suburban commuters over the Black and Jewish communities in its path. The construction of this 1.4-mile elevated viaduct forcibly displaced nearly 1,300 15th Ward residents and businesses and left a legacy of disinvestment in its wake. What had formerly been one of the densest parts of the city was transformed into acres of abandoned property. Many Black residents, even if they had the means to move, were unable to because of redlining, having little option but to live around the declining conditions of the new highway. These effects are still felt today and contribute to wealth disparities across the Central New York region.

The removal of I-81 viaduct through the city center, the physical manifestation of the policies perpetuating inequality, has the power to change this status quo and heal Syracuse’s 60-year divide. For this reason, the Community Grid alternative, which would remove I-81 and restore Syracuse’s street network in its place, gained widespread support when the New York State Department of Transportation began to consider what to do with the crumbling highway over a decade ago.

While NYSDOT should be applauded for taking this momentous first step toward removing the highway, there is still much to be done. NYSDOT’s plans don’t take into account the project’s ramifications other than its traffic impacts. In particular, it says little about the effects it will have on the residents who live around it. While residents prefer to see the highway come down, they are skeptical that they’ll receive any of the benefits of removal and fear instead that they will be priced out of the neighborhood as removal gets underway. To ensure more equitable outcomes, the New York Civil Liberties Union has worked with members of the community to create recommendations NYSDOT should adopt, including the creation of a community land trust to steer the development of land reclaimed from the highway. This is just one of the ways that NYSDOT can be more intentional about empowering the community’s vision for the corridor after the highway.

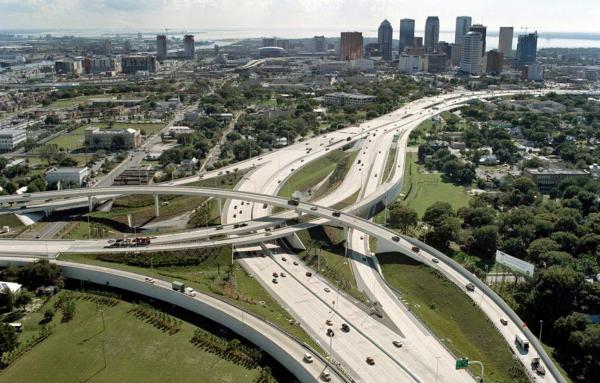

Interstate 980, Oakland, California

Construction on I-980 had started in 1962 but had stalled out several times in the face of lawsuits that cited significant environmental and housing concerns. A portion of the right-of-way had already been cleared, leaving a no man’s land separating parts of West Oakland from the rest of the city. Finally, in 1977, the City of Oakland decided I-980 was crucial to its economic development efforts and the residents of primarily-Black West Oakland realized they had leverage. The partially constructed freeway was already a barrier, so why not get something in exchange for letting the City proceed with its plans? In the end, residents secured new housing and rent protections from the city and some of their houses in the highway’s path were even relocated.

Thirty-five years later, the residents of West Oakland now have leverage again, as I-980 approaches the end of its designed lifespan and the city decides whether or not to dismantle the highway. There are many potential advantages to removal. The highway inhibits West Oakland residents from easily accessing downtown on foot and by bike, with a daunting route that consists not only of the Interstate, but also a pair of frontage roads that serve fast-moving traffic. Furthermore, the highway is largely underutilized, carrying only 53 percent of its potential capacity, mostly local traffic with both origins and destinations along the northern part of the corridor.

Advocacy group ConnectOakland has developed a vision for removal that addresses both these local as well as regional mobility needs, in addition to other community goals. Designs remain flexible to achieve the best solution possible for the residents who live along the I-980 corridor but crucial components include: the replacement of the highway with a roughly 75 percent narrower street, the reconnection of at least 13 cross streets severed by the highway, the potential to incorporate regional transit (including a new BART line) into the current right-of-way, and the reclamation of around 17 acres of land for new development.

Housing also comes to the fore in these discussions. The land reclaimed from the highway could be developed for any type, use, or intensity that will best serve West Oakland’s residents, including affordable housing and community services that prevent displacement. ConnectOakland thinks removal is worthwhile only if the city and other agencies that oversee it cede much of the design and planning process to community members, so that it’s their vision for the neighborhood without the highway that gets built.

To learn more about the other highways in Freeways Without Futures 2021, download the report here.