A federal Highways to Boulevards program is the infrastructure project a healthy and equitable America needs

Editor's note: Join us Tuesday, August 25th, for On the Park Bench: Equity-Driven Planning, a 2 p.m. (Eastern) webinar with Mitchell Silver, New York City Parks Commissioner, who will exhibit a variety of ways that equity, inclusivity, and diversity can enhance and enrich the urban realm. Register in advance.

Want to support a federal highways to boulevards program? Sign the petition!

Over 50 years ago, the Federal-Aid Highway Act launched the construction of the federal Interstate system, remaking the American landscape with more than 47,000 miles of highway as the most expensive infrastructure program to date. In the name of progress, highway builders forcibly removed hundreds of thousands of primarily Black and Brown Americans from established communities to make way for roads that served to increase access and eventually generate wealth for white suburbs. In many cities, these highways exist as monuments to racist planning and financial practices that value the convenience and mobility of white, suburban commuters over the largely communities of color who stand in their path.

We continue to see, in cities across the country, the injustices in the built environment that stem from this era of highway building and support the separation of cities by race and class. Today, many of these crumbling urban freeways are reaching the end of their designed lifespans. As debates at the federal level start to consider infrastructure as a cornerstone for recovery from COVID-19 and Americans are evaluating how to address systematic racism, where do urban highways and their legacy fit in? Will we reinvest in these structures, continue to support highway expansion, and solidify physical barriers that separate and destroy? Or can we envision a reparative infrastructure program that reknits communities and begins to address the damage these highways have caused?

The Highways to Boulevards movement offers a path forward for communities to repair, rebuild, and reknit. It seeks to replace aging highways, out of context with their surroundings, with city streets and boulevards that include cars, but do not make them a priority. These streets become places for the people who live around them, with local businesses and places for public interaction, as well as better integration with a city’s transit systems. Highways to Boulevards conversions increase access and allow for the creation of neighborhood-driven, well-functioning space. To date, 18 American cities either replaced or committed to replace a freeway with more urban streets.

But more work needs to be done to bring this restorative effort to more cities and towns nationwide. Federal policies and funding created these highways and a federally funded highways to boulevards program is necessary to reknit the urban fabric. The potential exists to unlock the social, economic, and environmental benefits of highway removal for hundreds of communities, most of them of color. This is not a technical problem; urban designers and transportation planners have the necessary toolkits ready to remove highways and avoid ‘carmageddon.’ Rather, it is a political problem.

Fortunately, there is already bipartisan traction at the federal level for a highways to boulevards program. The Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works has unanimously advanced in a vote of 21-0 their FAST Act reauthorization bill (S.2302) that includes the Community Connectivity Pilot Program, which would fund the study and removal of outdated highways in urban contexts as a path toward community revitalization. On the House side, 42 members have co-sponsored a similar program, the Connect Communities Program, as part of the Build Local, Hire Local Act (H.R. 4101).

A federal highways to boulevards program will not be a silver bullet for community restoration, but it would begin to address many of the underlying inequalities in the built environment brought to public attention by the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing and increasingly public police violence against Black Americans. It can be a truly reparative program that puts communities first and offers remedies to the injustices inflicted by highway building.

Here’s why Congress should support it.

The historic cost of highway building

The construction of the federal Interstate system did not come without a significant human cost.

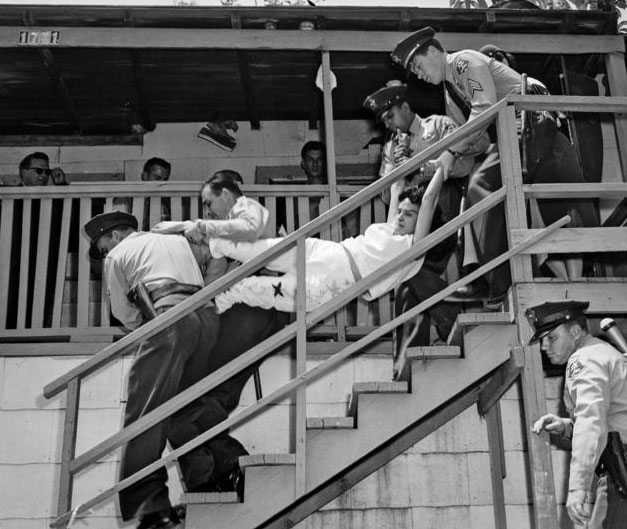

Under the framework of ‘urban renewal,’ highways were built through cities across America, displacing hundreds of thousands of people through eminent domain seizures and creating an unhealthy preference for driving fast at the expense of the communities in their paths. Highway construction divided many neighborhoods in two—their main streets demolished and businesses closed, disproportionately in Black and Brown communities, whose campaigns to resist highway building often did not have the political resources and connections of their white counterparts.1 They felt the impact of highway construction immediately, from dislocation to the destruction of places central to the community.

A total number of people that highway construction displaced has never been calculated, but estimates and available data suggest at least one million, if not more.2 Government records from the heyday of highway building support such a total. The 1965 Congressional report Study of Compensation and Assistance for Persons Affected by Real Property Acquisition in Federal and Federally Assisted Programs, published at the end of what the Federal Highway Administration describes as ‘the greatest decade’, reports the average number of families and individuals displaced per year in a three-year period between 1961 through 1963.3 During that time, federally-funded highway building displaced 97,185 families and individuals from their homes, of which 82 percent lived in urban areas. The study estimates that highway construction would displace an additional 185,645 families and individuals over the next 8 years. The report concedes that these numbers were ‘astoundingly large.’4

Other noxious effects of highway building are simply unquantifiable. Mindy Thompson Fullilove has studied the trauma and social disintegration, the ‘root shock’, that resulted from the destruction of minority neighborhoods during the period of urban renewal. In part, this came from the forcible relocation of thousands of community members, who in many cases were given 90 days or less to leave and no compensation for moving expenses.5 But for those who stayed, they witnessed the state-sanctioned destruction of the landmarks in their communities. Highways erased focal points for Black and Brown communities, such as the tree-lined Claiborne Avenue in New Orleans, the ‘Little Broadway’ of Overtown in Miami, and the church El Santuario in Segundo Barrio, El Paso. After the highway, these areas were no longer recognizable, or as the Miami Times describes Overtown during the construction of the freeway through it, that it looked like ‘something like a king-sized tornado had hit the place.’

In the shadow of the freeway

Some of the communities in the path of highways unraveled to the point of disintegration. When Rochester, NY opted to remove its Inner Loop and replace it with a boulevard, residents recognized that the community living around the highway was no longer the same. “You’re creating a new neighborhood that hasn’t existed in over 50 years,” said Shawn Dunwoody, a community organizer in the city.

Other Black and Brown communities have taken back the space underneath the highway and incorporated it into their public realm. This ranges from a temporary transformation of the space, like the second-line processions that wind their way underneath the New Orleans’ Claiborne Expressway, to permanent amenities, like the creation of Chicano Park in San Diego underneath the Coronado Bay Bridge/I-5 interchange. In the case of Chicano Park, demonstrators who lived adjacent to the proposed interchange persisted in their demands that the California Division of Highways honor its early promise to build the park.6 Now, the much-frequented park hosts the largest outdoor display of murals in the world, painted on the pylons of the interchange by local artists in the tradition of Mexican muralism. As Eric Avila, author of The Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City, describes it, the park has become the ‘symbolic heart of the barrio’ and folds the construction of the interchange, and the protests around it, into the cultural memory of Barrio Logan.7

Still others found themselves new inhabitants of a neighborhood consumed by a highway, as longtime residents who had the means to do so moved out. After the California Division of Highways built Interstate 5 through Boyle Heights in Los Angeles, a significant portion of the neighborhood’s Jewish population moved away to the Westside. In their place, a generation of Mexican immigrants, seeking inexpensive housing, moved in, inheriting only the small sliver of Hollenbeck Park the highway didn’t destroy.

No matter how people came to live around highways, they face ongoing negative physical and psychological impacts. Highways have burdened them with the hazards of vehicle exhaust, severe disinvestment, a loss of local businesses, services, and amenities,8 and streets that are dangerous to pedestrians. If Americans are truly committed to resolving longstanding racial (and spatial) inequalities, removing the urban highways that enforce them is one path forward, which would impact no small number of people: in Southern California alone 2.5 million people live within 1000 feet of a freeway,the distance which its pollution is known to have severe negative health effects. Some might argue that the presence of a highway keeps housing in the nearby neighborhoods affordable, and they’re not wrong. But this is a false dichotomy, if we are willing to implement other solutions to keep housing costs reasonable. No one should have to choose between an affordable place to live and a toxic one. We can do better. Here’s how.

The community benefits of highways to boulevards

Highways to boulevards projects aren’t just about changing the way we travel within our cities. They articulate a community vision for a neighborhood without the freeway, transforming broken liabilities into assets that support socially and economically valuable places. What replaces the highway’s massive right-of-way might vary (a boulevard, a restored street network, parks and green spaces, homes and apartments, stores and shops, public services and amenities, or some combination of all these), but the benefits are largely the same:

- A healthier environment

Choosing city streets over freeways means leaving behind the hazards of highly concentrated vehicle exhaust near residences, businesses, and schools. Many urban highways run through the densest parts of their cities, exponentially increasing the number of people exposed to toxic fumes and particulates from cars and truck traffic. Known health risks from proximity to highwaysinclude increased rates of respiratory ailments and cardiovascular illnesses. It is unsurprising, perhaps, that the largely minority communities living alongside highways are more susceptible to COVID-19.

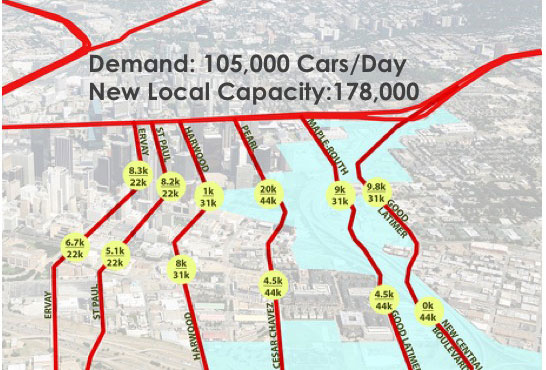

It is a common misperception of highways to boulevards projects that any one street that replaces the highway needs to carry the same amount of traffic as the highway and so pollution will remain just as concentrated. This is fundamentally untrue. Long-haul traffic that would travel through the city on a freeway will seek alternate highway routes outside the city, many of which add no more than a few minutes of travel time. Local traffic will disperse among multiple, parallel streets within a city, depending upon where they are traveling to. Traffic can be reduced even more if the new street design incorporates public transit and/or multi-modal infrastructure like bike lanes. With traffic dispersed, pollution from vehicles is kept below dangerous thresholds in any one area.

- Increased access to quality public spaces and green spaces

One in three Americans don’t live within a ten minute walk of a park. Once again, perhaps unsurprisingly, this access is defined along the lines of race and class.The same goes for streets friendly to pedestrians, not dominated by automobiles, where one can move comfortably on well-maintained and continuous sidewalks. Around highways, these disparities are even more pronounced, with whatever green space that exists subject to the noise and pollution of the road and city streets connected to a highway full of fast-moving cars. In the age of social distancing, this leaves residents with few safe options for spending time outside in public.

Highways to boulevards projects begin to remedy both of these disparities. Many have already reclaimed significant portions of a former highway’s right-of-way as community green space, with additional calls for similar transformations.9 The city streets built in place of highways, when designed to prioritize pedestrians, are more humane and easier to cross and navigate. Unlike a highway, dedicated to a single function (moving traffic quickly, although anyone who has ever experienced rush hour realizes they often fail at this too), streets and public spaces dedicated to people, not cars, offer members of the community places to relax, shop, and enjoy each other’s company in public. Places like these were destroyed to make way for freeways. Now, the opportunity presents itself to create a new, vibrant public realm for the communities that bore the brunt of highway construction and are most in need of these amenities, both in the short and long term.

- An opportunity for affordable housing

The benefits of highways to boulevard projects also come with potential pitfalls, many of which can be avoided if cities take proactive measures at the start. One of these is the risk of a more subtle form of displacement. The removal of a highway will increase the attractiveness of nearby neighborhoods, and subsequently property values and rents can be expected to rise. In this scenario, lower-income families and individuals who currently live around a highway will find they can no longer afford to stay. This should not be the outcome. The benefits unlocked by taking down an elevated expressway must be channeled to serve the members of the current community.

With planning, attention, robust and meaningful outreach, and strong fiscal tools, long-standing members of a community need not be displaced when a freeway comes down and the market responds. From the beginning, cities need to develop active strategies to combat potential displacement.

The creation of affordable, attainable housing is one place to start. Much of the land currently occupied by freeways will revert to the control of cities upon their removal. Some of this land should be dedicated to the creation of housing options at many price points, from below market rate to market rate, to ensure choices for the most vulnerable renters and prospective homeowners in the community. Other protections should also be put in place to keep current residents in their homes, including tax abatements for property owners, rent control and first-time homebuyer programs for tenants, and community land trusts to steer new development.This short list is far from exhaustive.10 Some examples of these affordable housing strategies in action in highway to boulevards projects can be found in Rochester’s redevelopment of the former Inner Loop and the the 11th Street Bridge Park project in Washington, DC, which is repurposing a decommissioned highway bridge into a community park.

- Supporting local business and job creation

One of the many benefits of walkable streets is that they are well-equipped to support local businesses,which channel more money back into their communities than their big-box counterparts. This has extraordinarily promising implications for highways to boulevards projects. First, by swapping highways for walkable streets, they are primed to attract new businesses to areas that are underserved in terms of amenities, mainly because of the presence of the highway. This must be balanced with protections for the existing businesses along the highway corridor, so that like residents, they too have the opportunity to benefit from the highway’s removal and are not displaced by a subsequent wave of gentrification. Programs to support new businesses that are community-oriented can help ensure the development of a complete neighborhood with a wide variety of services, amenities, and cultural institutions.

Highway construction is often touted as an engine for job creation, but many of these opportunities are temporary. Highways to boulevards projects create more, longer lasting jobs after the dust has settled. While many of these jobs come from the businesses that develop around the improved city streets, highways to boulevards projects also offer other creative opportunities for employment programs. If cities incorporate public transit into the streets that replace a highway, they can also create programs that train local residents as operators, conductors, and station personnel for public transportation projects, which create more jobs per dollar spent than highway construction. Public-service jobs, including public transportation, have been a historical path for Black Americans to wage security and upward mobility and robust highways to boulevards projects featuring public transit can continue that trend.

- A balanced transportation ecosystem

Highways to boulevards projects offer a chance for cities to recalibrate their transportation options and divest from the expensive automobile infrastructure that acts as a barrier to safe pedestrian travel. The new streets or boulevards that replace highways can incorporate relatively inexpensive forms of public transportation into its design, such as bus rapid transit with dedicated lanes. Many of the minority communities who live around highway corridors lack effective public transit, even though they rely upon it; highway removal is an opportunity to remedy this and provide less expensive options for accessing quality and well-paying jobs without long commutes. Car commuters pay an average of $9,737 per year for a household to own and maintain their vehicle, which becomes especially burdensome for individuals and families with lower incomes, as this represents a higher percentage of their annual income. Ideally, if transit were sufficiently effective, they could forego this expense.

Targeted public transit investments, coupled with highways to boulevards projects, can transform how people move in and around a city. A street design that includes cars but does not make them the highest priority is key for these projects: the test of time has shown that a road of four to six lanes is adequate for auto traffic but can still be designed for transit, bicycles, and people, with well-proportioned sidewalks, frequent and well-signed crossings, street trees, and one or more medians that create a desirable and walkable avenue.

Eight uninterrupted lanes of at-grade traffic for a boulevard will not do; it will still be a dangerous barrier for pedestrians, businesses that are supposed to rely on foot traffic will flounder, and property values will remain stagnant. Only by balancing multiple modes of transportation will the full community benefits of highways to boulevards projects become realized.

A community-first highways to boulevards program

Most importantly, highways to boulevards projects will not deliver all the benefits listed in this article unless they are driven by and designed in partnership with the communities who live around these highways. These residents are not only most impacted by the projects, they also live day to day with the ongoing trauma of living in a neighborhood severely damaged by federal infrastructure projects that do not benefit them.Yet there can be serious barriers to meaningful engagement and getting buy-in from legacy residents. Some may reject highways to boulevards projects as a second round of state and local government sponsored displacement, and trust-building with designers and organizers should be a large part of this work.11 State and local governments will need to demonstrate they can and will follow through on promises to unlock the benefits of highway removal for these existing communities and prevent their displacement.

The federal government can set an example by making any funding available to cities and states for highways to boulevards projects contingent upon enacting programs that prevent resident displacement, support existing and new community-oriented businesses, and provide public transportation options.

The ramifications of not including these protections at the federal level are dire and we should learn this lesson from previous highway legislation, which historically has set few stipulations for how funds are spent.12 But there are promising signs that we have begun to learn. The highways to boulevards program drafted in H.R. 4101 (the Connect Communities Program) includes several provisions that address these issues and they should be incorporated into any highways to boulevards program that becomes law. Otherwise, it will fail to become the reparative infrastructure program that America needs.

1This is not to say that highway building did not affect other communities as well. In Boston, the construction of the Central Artery through Chinatown displaced a large part of the Asian-American community living there. Even white communities found themselves threatened by the highway builders, but they typically had more resources to fight construction and stop the bulldozers.

2Alan A. Altshuler, The City Planning Process: A Political Analysis (Ithaca, NY,1965), 339.

3Note that the report counts ‘families’ as a single unit when tallying the number of people displaced and so obscures the actual total.

4United States. Congress. House. Committee on Public Works. Select Subcommittee on Real Property Acquisition, Study of Compensation and Assistance for Persons Affected by Real Property Acquisition in Federal and Federally Assisted Programs (Washington, DC, 1965), 105.

5United States. Congress. House. Committee on Public Works. Select Subcommittee on Real Property Acquisition, Study of Compensation and Assistance for Persons Affected by Real Property Acquisition in Federal and Federally Assisted Programs (Washington, DC, 1965), 24-26, 36.

6The California Division of Highways had originally promised to build a park underneath the interchange, but then reneged and announced its intention to build a highway patrol station there instead.

7Eric Avila, The Folklore of the Freeway (Minneapolis, 2014), 167-170.

8The Study of Compensation and Assistance for Persons Affected by Real Property Acquisition in Federal and Federally Assisted Programs also documents the number of businesses displaced by highway construction in urban areas, which tallies a total of 7,389 over a three-year period. Nearly 25% of the businesses displaced by highways never reopened.

9Prominent examples can be found in Chattanooga, TN and Portland, OR.

10Andre Perry’s book Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities contains a more complete list of strategies, particularly in the chapters “A Father Forged in Detroit” and “Buy Back the Block.”

11This is the case for many Black residents of West Oakland, who see the potential removal of I-980 as another infrastructure project to their detriment. When the highway was under construction in the 1970s, West Oaklanders leveraged their position to get affordable housing built in exchange for dropping a lawsuit against the highway’s construction.

12The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which brought the Interstate system into being, serves as the cautionary tale. Prior to becoming law, the House of Representatives voted to include funds for family relocation costs into the highway legislative package. This would have by no means stopped the displacement of hundreds of thousands, but it would have at least required that they were compensated. Instead, the Senate balked at the notion and compensation was not included in the final bill, leaving states to deal with it as they wished. As of 1965, only 22 states had established moving compensation programs, leaving more than half of those displaced without any compensation and trapped in a spiral of poverty.