Landmark plan guides downtown revival

In the last quarter of the 20th Century, city revival efforts were characterized by big “silver bullet” ideas, such as convention centers, aquariums, festival marketplaces, and waterfront malls. These often involved tearing down historic fabric and replacing it with lifeless streetscapes, disconnected from the rest of the city.

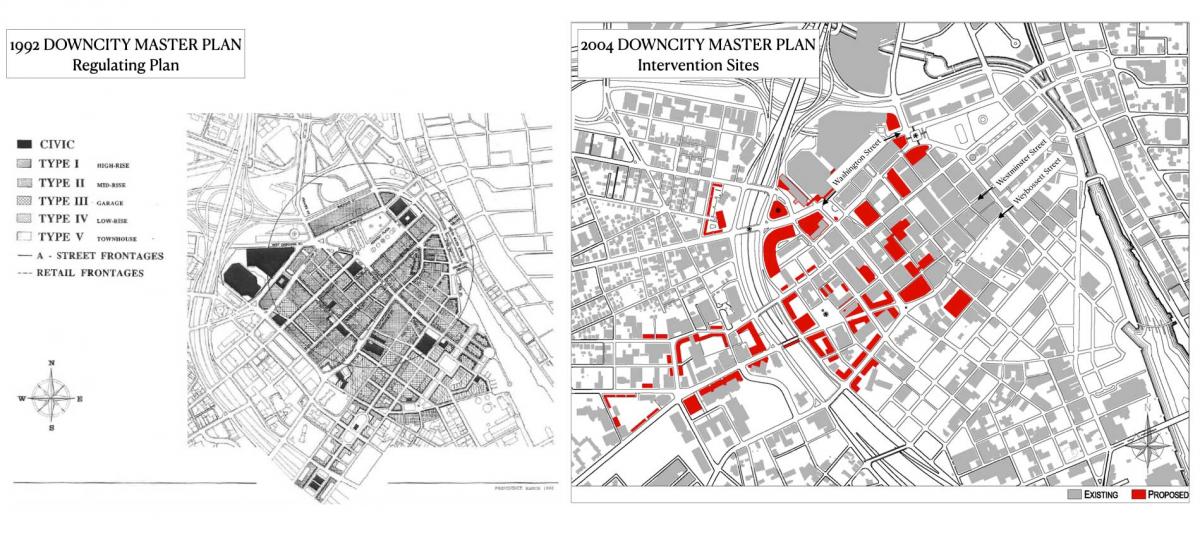

The Downcity Plan in Providence, Rhode Island, created in a series of charrettes from 1992 to 2004, pioneered a radically different approach of “bite-sized interventions” that capitalized on the city’s wealth of historic architecture, underutilized buildings, and intimate streets. Furthermore, it made sense because the City had limited investment capital for big projects.

The designers quickly recognized that “smarter, more strategic, and smaller-scale investments and policy adjustments were in order for the half-mile radius around City Hall,” the DPZ CoDesign planning team told CNU. “The other customized approach was rationalizing the activities of the private sector by grouping the buildings of Downcity into coherent ‘Pilot Projects’ and assigning them to ‘Custodians,’ drawn from a roster of private and corporate citizens which manifested their support. This created both direct oversight and accountability.”

This approach won the design team and key developer a special Generational Project Charter Award from CNU. David Brussat, long-time resident and editorial writer in the City, commented on the plan’s cumulative effect: “The Downcity Plan has preserved the beautiful buildings of downtown but not the seedy lifestyle that prevailed after the dark clouds of urban renewal sent urbanity fleeing from downtown. … The downtown of 2016 [or of 2023, for that matter] is not much different in appearance than the downtown of 1984, when I arrived. What is different is the little things. It is cleaner. There are more people. The faux façades are gone. There are more trees. The sum of all these little things is one big thing: there is more vitality.”

Nearly 2,000 apartments have been built over 550 acres of downtown, many in converted old buildings such as Westminster Lofts (287 units, 25 percent workforce housing) or new buildings that blend in with the old, such as Nightingale (143 units). Retail totals 84,000 square feet in 40 sites across 13 buildings, and office space totals 263,000 square feet in eight buildings.

The Downcity Plan envisioned a series of small, quality public spaces, such as Freeman Park, a 3,800-square-foot space memorializing a Providence urbanist, Robert E. Freeman. Freeman Park was conceptualized by the planning team in the early 1990s. Gaebe Commons on the Johnson and Wales Campus was addressed during one of the later Downcity charrettes in the 1990s. Grant's Block Park, recently opened, is a 4,000-square-foot pocket park with fixed and movable cafe seating, and a 1,700-square-foot dog park, fronted on one side with a liner building. The idea of active-use liner buildings fronting public space has been a consistently successful Downcity Plan strategy.

The Coalition for Community Development partnered with the City of Providence to sponsor the master plan charrettes. Developer Cornish Associates, led by Buff Chace, has been most active in implementing the plan recommendations. They have been a partner or owner of 18 projects in the downtown neighborhood since the original charrette. Of the total, they continue to manage 13 through a property management company. “Twenty years ago, they founded a marketing and programming entity to support the commercial tenants and provide activation of the downtown,” according to DPZ.

Downcity Plan was published in Peter Katz’s influential 1994 book, The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community, and predates the Charter of the New Urbanism (1996), which DPZ cofounders Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk helped to author. Due to that publishing, the Downcity Plan was widely known outside of Providence, but it also had an ongoing impact locally. The Plan supports Charter principles in important ways, DPZ says.

- The approach to development conserved and reinforced the existing historic fabric, channeling economic investment to foster the social energy that was missing. Key to the latter was the conversion of historic buildings into residential lofts to restore 24/7 living to the downtown. The form-based code incentivized the conversion of ground floors in former office buildings to house the restaurants, shops, and pharmacies needed by the new residents.

- New residents encouraged an impressive array of arts institutions to reinvest in Downcity: the Trinity Repertory Theatre, the Providence Performing Arts Center, the Black Repertory Theatre, and AS220. Johnson and Wales University further committed to its downtown campus with its own master plan that was a direct extension of the 1992 Downcity charrette.

- The Downcity Plan initially focused on a network of activated sidewalks along three principal streets (Weybossett, Westminster, and Washington) identified as key corridors to be restored and completed to connect the city core to West Side neighborhoods. Strategically located redevelopment projects completed this network of streets, making them safe and appealing with the added residential and commercial activity.

The most important contribution of the plan was to direct the renewal of Downcity’s legacy of historic, largely abandoned buildings. Today, nearly 20 buildings have been revitalized into mixed-use and housing in a thirty-plus-year mission of investment in and reanimation of downtown. “Starting with five deteriorating turn-of-the-century buildings behind Providence City Hall, the plan demonstrated the transformative power of collaboration. By uniting architects, government officials, and community members in the planning process, each group became invested in the outcome,” DPZ says.

The 2025 Charter Awards will be presented at CNU33 in Providence, Rhode Island, on June 12.

Downcity Providence Master Plan, Providence, RI:

- DPZ CoDesign, Principal master plan design firm

- Cornish Associates, Developer

- Buff Chace, Managing Partner, Cornish Associates

- Thom Deller, Town Planner, Town of Johnston, RI

- Daniel Baudouin, AICP, former Executive Director of The Providence Foundation

- Richard Godfrey, Chair of the Steering Committee, Planner

- Francis Scire, Member of the Steering Committee

- Karina Wood, Member of the Steering Committee

- Christopher Ise, Member of the Steering Committee, planner

- Additional partners, Johnnie Chace; Steve Durkee; Ari Heckman; Russell Preston; David Cicilline; Joanna Levitt; Bob Azar; Lynn McCormack; Karen Beebe; Jerry Elrich; Curt Columbus; Douglas Storrs; Cliff Wood; Donald Powers; Dave Brussat ; Todd Zimmerman; Clark Schoettle

2025 CNU Charter Awards Jury

- Rico Quirindongo (chair), Director, City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development

- Majora Carter, CEO of Majora Carter Group in the Bronx, New York City

- Jake Day, Maryland Secretary of Housing and Community Development

- Anne Fairfax, Principal, Fairfax & Sammons in New York, NY, and Palm Beach, FL

- Eric Kronberg, Principal, Kronberg Urbanists + Architects in Atlanta, GA

- Steven Lewis, Principal, ZGF Architects in Greater Los Angeles, CA

- Donna Moodie, Chief Impact Officer, Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle

- Joe Nickol, Principal, Yard & Company in Cincinnati, OH