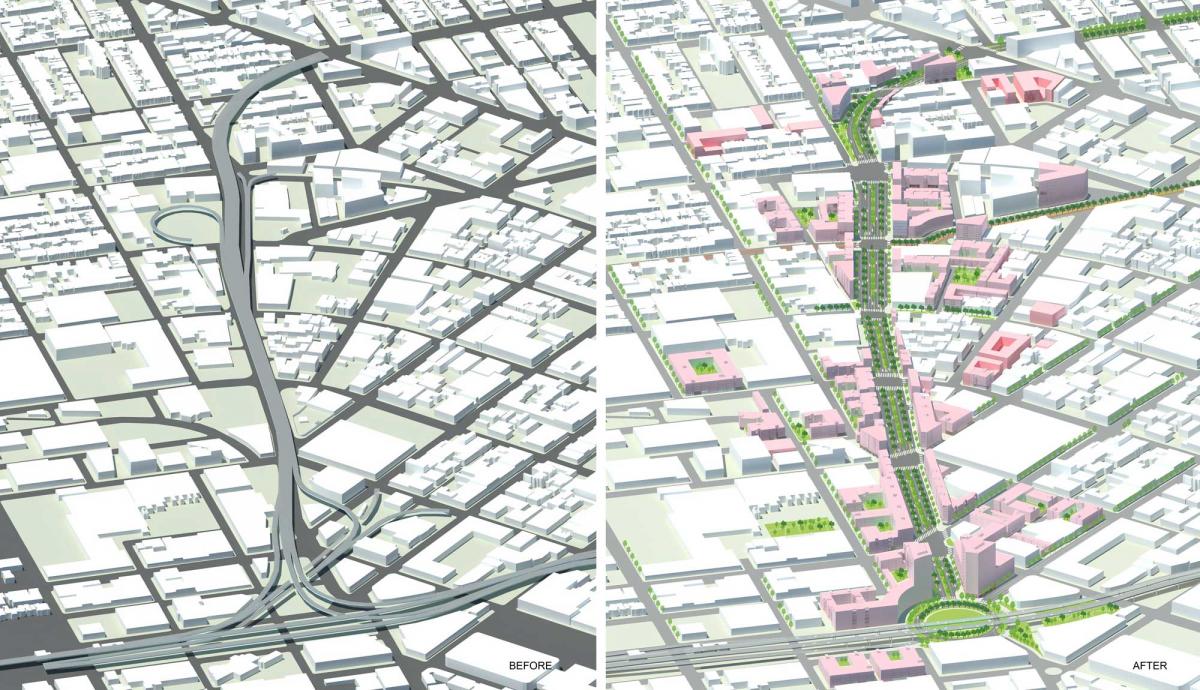

Urban repair through freeway removal

San Francisco is a beacon of freeway removal, largely due to a 1989 earthquake that damaged two elevated highways—causing them to be taken down and their rights-of-way converted to boulevards. A mile-long section of the Central Freeway was demolished and rebuilt as the Octavia Boulevard, repairing neighborhoods in the Hayes Valley. Now a University of California-Berkeley plan proposes to extend that successful demolition a mile further—all the way back to the I-80 interchange.

The removal would open the corridor up to new development, including up to 4,000 new housing units, mixed-use development, and two small parks on 30 acres of parcels along the route. It would help to knit together three separate areas of city grids, and alleviate problems of traffic coming off of the current freeway spur onto Octavia Boulevard.

“The student (Qingchun Li) exhibited a real understanding of how to transform a highway to a boulevard, what sold the project to me,” notes Amy Stelly, juror, urban planner, and freeway removal activist from New Orleans. “The plan showed a depth of understanding of what this means and how to do it.”

The removal of the Central Freeway spur is an important next step in repairing damage done to San Francisco during the freeway-building heyday of the middle 20th Century. This removal was recommended in CNU’s 2014 report A Freeway-Free San Francisco.

The proposed new boulevard section will disperse the freeway traffic onto the surrounding street network. A tangle of off-ramps from I-80 now funnels traffic onto a few streets. Li proposes a large new traffic circle at the exit, allowing traffic to disperse in many directions.

“The removal of congested pinch-points will enable public transit to run more freely and provide a safer environment for cyclists and pedestrians,” Li says.

The damaged blocks along the freeway will offer opportunities for housing. The plan proposes urban design guidelines and a form-based code to define the pattern of development. Small parcels, active street frontages, scaled height and bulk limits, and a range of building types will enable the new development to blend into the existing context.

The existing neighborhood includes some blue-collar employment and low-income housing. Retaining these elements will help maintain the City’s jobs/housing balance. Promoting of affordable housing in new development would help prevent gentrification and displacement. Keeping parcels small would promote a variety of building types and match the scale of the existing urban fabric.

“The proposed extension of Octavia Boulevard replacing the existing stub of the Central Freeway from Highway 101 to Market Street would complete the ambitious plan to rid San Francisco of one of its most egregious mistakes,” notes one critic at UC Berkeley. “This part of [the city] has long been blighted by the ugly, noisy freeway and its presence has caused the surrounding neighborhoods to be marginalized and blighted. This imaginative proposal will help revive this part of the City and create opportunities for much needed new housing.”

Urban Repair After Removal of Central Freeway

- Qingchun Li, University of California, Berkeley

2021 Charter Awards Jury

- Goeff Dyer (chair), Master Planning and Urban Design Strategic Lead, B&A Planning Group

- Amy Stelly, Artist, designer, urban planner with Claiborne Avenue Alliance

- Marques King, Economic Development and Design Manager with Jefferson East, Inc.

- Alli Thurmond Quinlan, principal, Flintlock Architecture & Landscape

- Andrew von Maur, Professor of Architecture at Andrews University