Ditch the ditch: Citizens respond to I-70 expansion

Note: CNU's sixth biennial Freeways Without Futures report was released April 3. I-70 in Denver was one of ten highways listed.

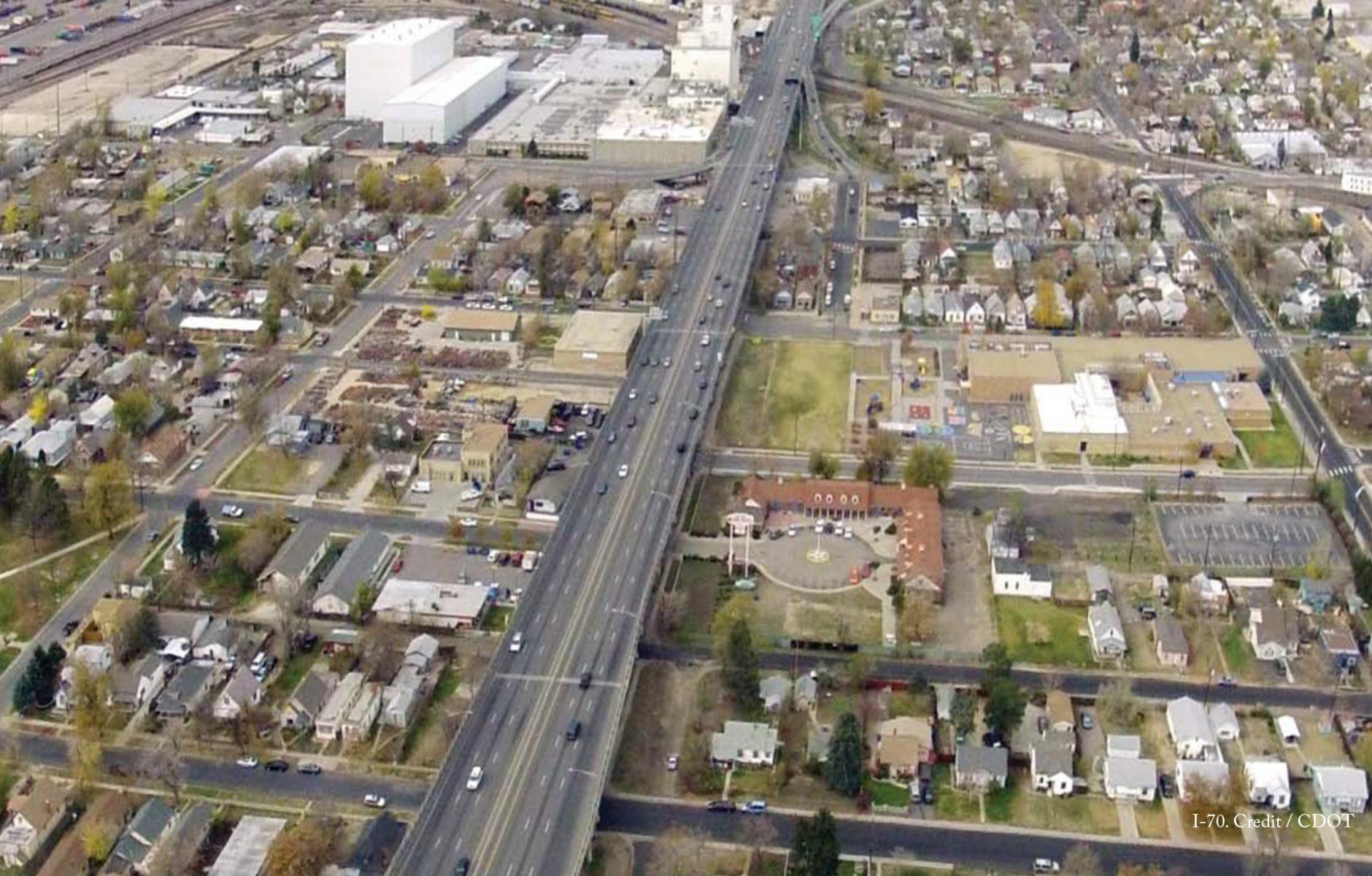

Highways are known sources of pollution. Air quality decreases significantly for residents who live within 1,000 feet of a highway. Yet in Denver’s Elyria, Swansea, and Globeville neighborhoods, CDOT is undertaking an expansion of I-70 that is displacing 56 residences and 17 businesses, and bringing even more of its residents into a 1,000-foot pollution threshold where vehicle emissions cause increased rates of asthma, heart attack, stroke, lung cancer and pre-term birth.

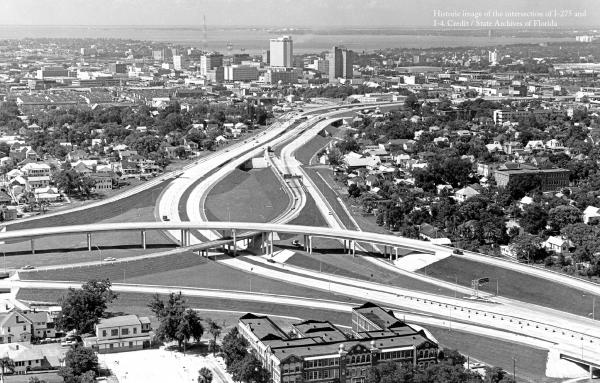

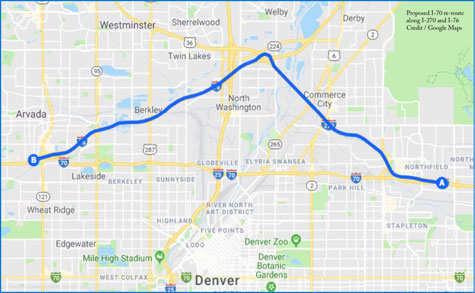

When I-70 was completed in 1964, the elevated highway diminished the value and changed the character of the primarily Latino neighborhoods along its course. Fifty-five years later, the aged viaduct needs significant repairs. Community organization Unite North Metro Denver proposed an alternative in place of the elevated highway. A tree-lined boulevard, with roundabouts instead of interchanges, would re-establish the community grid, free up land for development, and raise property values. The proposed boulevard would cater to local traffic and incorporate alternative transportation options like bus rapid transit and bike lanes to decrease the number of drivers on the road. Traffic with destinations beyond the city would be diverted to the north of the current alignment onto I-76 and I-270, which only adds 2 miles to the total distance through traffic would have to travel.

Instead, CDOT has so far opted to replace and expand the highway. In August 2018, it broke ground on the $1.2 billion Central 70 project, one of the most expensive projects ever undertaken by the agency. Over the next 44 months, CDOT will remove I-70’s elevated viaduct and replace it with a sunken freeway nearly three times as wide. The project has serious repercussions for the neighborhoods around it. Although CDOT has offered a “cut-and-cover” deck to add green space to the area, pedestrian connections across the highway will be limited to only nine locations between Brighton Boulevard and Colorado Boulevard, whereas previously individuals on foot were able to cross anywhere underneath the viaduct. Among the businesses the state must seize and demolish is one of the few groceries in the area. The plan also includes the demolition of Swansea Elementary School’s original playground, with a CDOT-funded relocation in the works. Post-construction, the school building would be directly adjacent to the 14-lane highway.

A second community group, Ditch the Ditch, has responded to the Central 70 expansion with environmental justice concerns. In addition to air quality issues, lowering I-70 below grade has the potential to contaminate groundwater sources, a fact that CDOT itself readily admitted when it shelved proposals to reconstruct I-70 as a tunnel.

In particular, Ditch the Ditch supporters took issue with CDOT’s proposed concession to the Swansea neighborhood. As a replacement for the demolished playground, CDOT proposed to cap a 4-acre area over I-70 and build a park above the highway. But with the rest of the road still uncovered, the children and others who used this green space would be exposed to the emissions from traffic below. The residents of the Elyria, Swansea, and Globeville neighborhoods, which all already belong to the most polluted ZIP code in the United States, would be subject to even more environmental hazards from the highway expansion.

With the support of the Sierra Club, several local organizations and neighborhood associations filed an injunction against the project on the grounds that it had not adequately addressed the environmental concerns for the community. As of December 2018, CDOT chose to settle the lawsuit and agreed to contribute $550,000 to an independent health study that will provide a greater understanding of public health and environmental hazards in the Globeville, Elyria and Swansea neighborhoods.

CDOT first proposed the reconstruction of I-70 in 2004. Fifteen years later, it runs contrary to recent transportation developments in Colorado. On the November 2018 ballot, voters turned down two proposals (Propositions 109 and 110) to allocate billions of dollars of funding to highway widening and expansion across the state. The state also elected Jared Polis as governor, who campaigned on the dual issues of cutting vehicle emissions and increased mass transit. In light of these developments, the Central 70 project appears to be behind the times—and proposals such as those by Unite North Metro Denver are more in line with current demands. Although CDOT has already broken ground and may be 20 percent finished with the widening by current estimates, the Central 70 project still has the potential to join 37 other urban highway projects across the United States that were halted mid-construction, by communities who saw a better way.