Proposed: A new California city

At the first Congress for the New Urbanism in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1993, planning Professor Robert Fishman described the concept of “mass suburbia” taking hold in America in the years after World War II. A synonym is “sprawl.” New urbanists have described the physical characteristics of sprawl, including separation of uses, the lack of centers, streets designed for fast-moving automobiles, and the obliteration of the neighborhood structure. In Fishman's account, this was done at a massive scale, backed by the US government.

He told of a three-pronged federal policy that took root in the Great Depression, when leaders were desperate to fuel demand in the US economy. The first prong was an “industrial housing policy” that included a bailout of the savings-and-loan industry, a new system of self-amortizing mortgages, and the creation of a suburban production-building industry. The second prong was a national automobile policy carried out by transportation engineers. Prong three, launched in World War II, was the defense policy that supported a suburban economic base, because the vast majority of defense factories were located outside the central cities. As such, Levittown, New York, which began production in 1947, was the culmination of new housing ideas and experiments, not the beginning. The result, materializing over several decades, was “a Broadacre City that is everywhere and nowhere,” Fishman explained.

Also at CNU I, planner Jonathan Barnett described how US cities grew before mass suburbia. Before the Great Depression, cities grew, in walkable ways, at similar velocities to the postwar building boom.

Incremental development proponents point out that the pre-War real estate industry comprised mostly small developers, but in the aggregate, the growth was massive. Look at the astonishing growth in Chicago from 1850 to 1930. The Windy City's population quadrupled in the decade before the Civil War. Then it maintained a growth of at least 100,000 people per decade, peaking at more than 600,000 new residents in the 1920s, before it all came to a grinding halt in the Great Depression. Although Chicago is an extreme example, other US cities, large and small, saw very high growth rates in that period.

And it wasn’t just the cities, and it began before 1850. French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville, in his classic Democracy in America, reported in 1836 that towns were founded in the US on a daily basis throughout the North, South, and West (now the Midwest). These towns were mixed-use and walkable. Many of them have since grown into cities. Postwar suburbanization was massive, but America was founded on a system of mass urbanism.

In the 21st Century, mass suburbia has slowed. Although substantial new housing is still being built in a sprawl format—less than it once was—development of other forms of mass suburbia, like shopping malls and office parks, has taken a nosedive. In his recent book Redesigning Urban Centers, Barnett writes that “The demand for urbanizing land … seems to have stabilized at about one-quarter of its peak in the late 1990s.”

New Urbanism, meanwhile, has made strong inroads into the real estate industry. It is now a known quantity, and most zoning codes have adopted at least some form-based standards, according to a 2025 study by the University of Chicago and Yale University.

And yet, New Urbanism remains much harder to build than it should be. It is common on infill sites where existing infrastructure makes walkable development the default option. Elsewhere, practitioners still report a slow, difficult process of getting walkable urban places from design to construction. Part of the problem is continued difficulty with codes, as only about one-third have strong adoption of form-based standards. But the bigger obstacle is the enormous issue of creating the bones of urbanism—the street network.

Fishman’s automobile policy was implemented by traffic engineers, and despite transformations in the real estate industry, this profession remains mired in the past. Wes Marshall, a former private sector traffic engineer who is now a professor at the University of Colorado, Denver, told the story in his 2024 book, Killed by a Traffic Engineer. The profession follows a standard practice that underlies sprawl. If outcomes fall short on safety or other societal goals, the responsibility never falls on the engineer—so long as standard practice is followed.

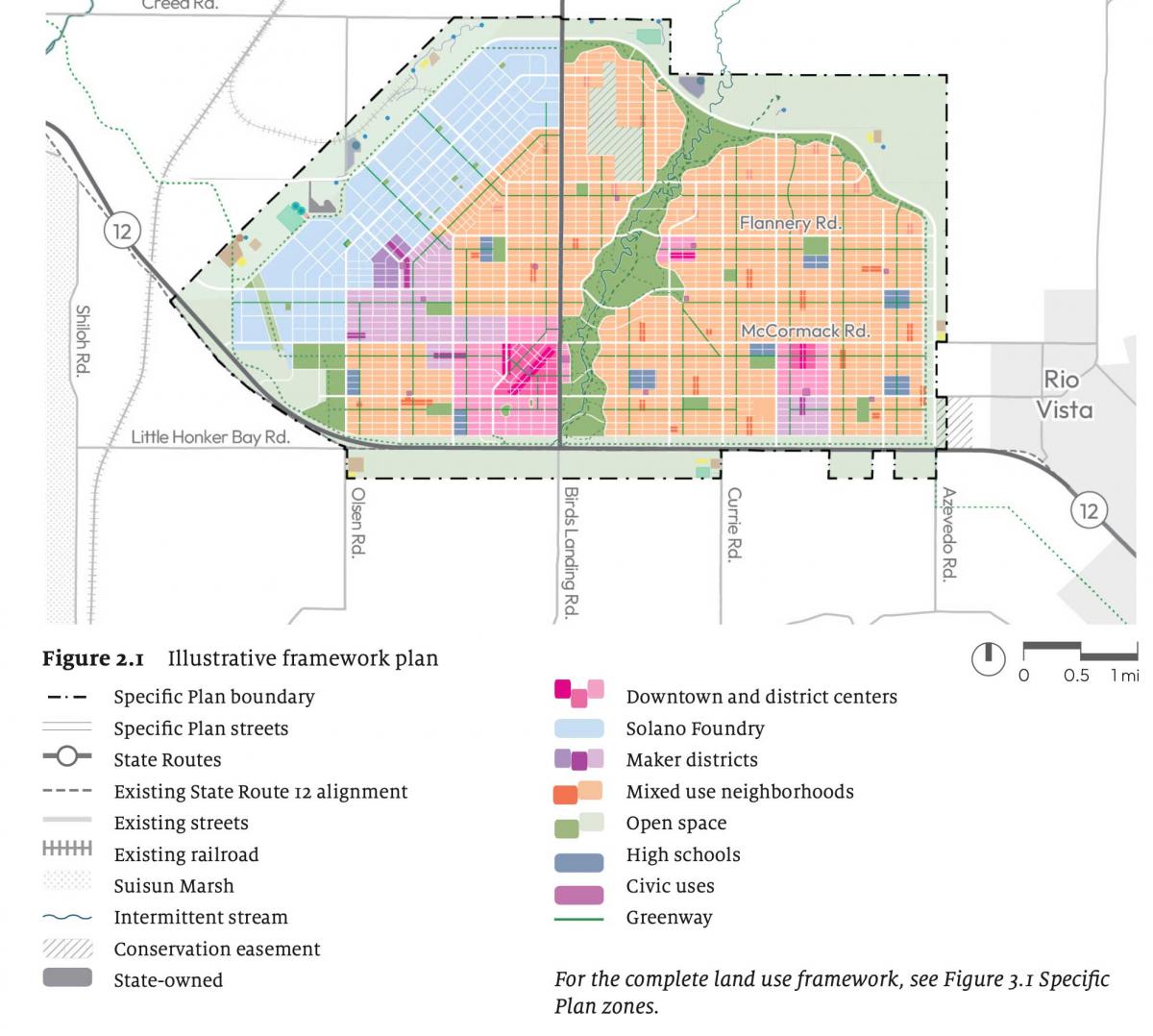

All of this brings me to California Forever, a new city of 400,000 population proposed in Solano County, California. The plan is New Urbanism on a scale that we haven’t seen before. Large New Urbanist developments have been built, like former airports Central Park (formerly Stapleton) in Denver, and Mueller in Austin, and the Daybreak project on reclaimed mining land in South Jordan, Utah. California Forever is approximately an order of magnitude bigger. “We have learned a lot from New Urbanism,” Gabe Metcalf, the head of California Forever planning, told CNU. “The scale is different. The biggest contribution we are making is in transportation. The rest is similar to what you are used to seeing.”

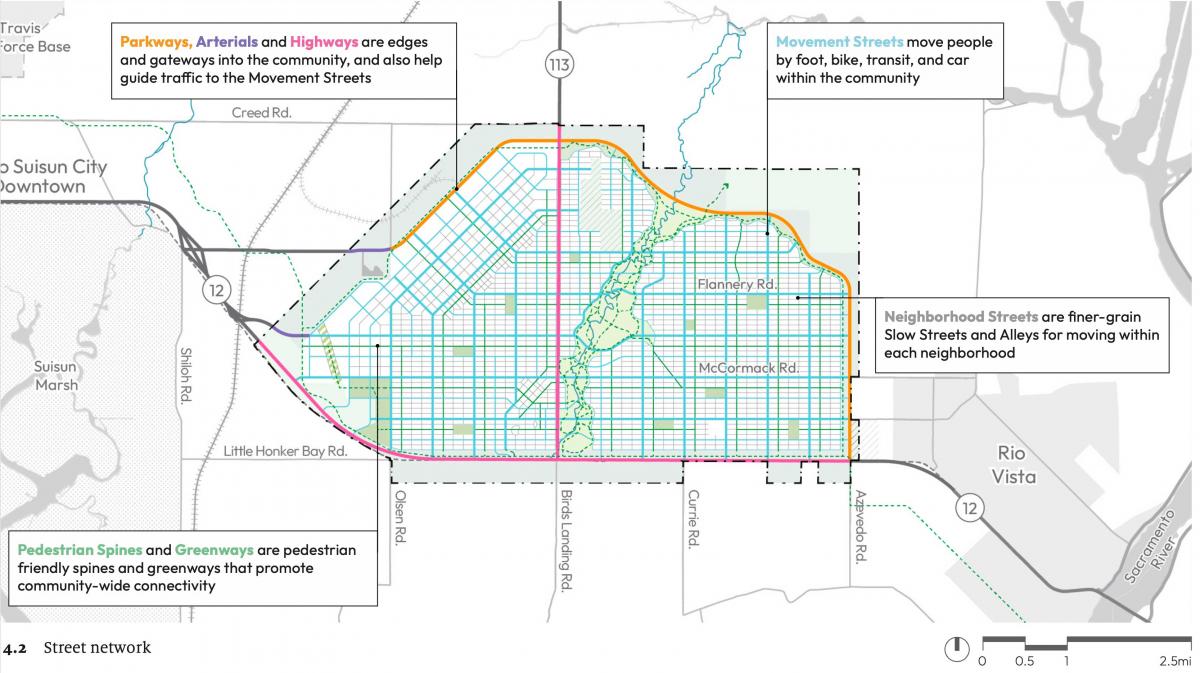

The plans were released in October in Suisun City (population 29,500), where annexation is proposed to incorporate California Forever. The scale of the project enables planners to propose a street grid for an entire mid-sized city, much like what was done in the 19th Century, using New Urbanist master planning techniques. The planners were inspired by 19th Century street grid extensions, such as the 1811 grid plan for Manhattan, still functional despite massive cultural and technological changes over two centuries, Metcalf says. “It’s a very flexible framework for change over time. They didn’t know what the uses would be.”

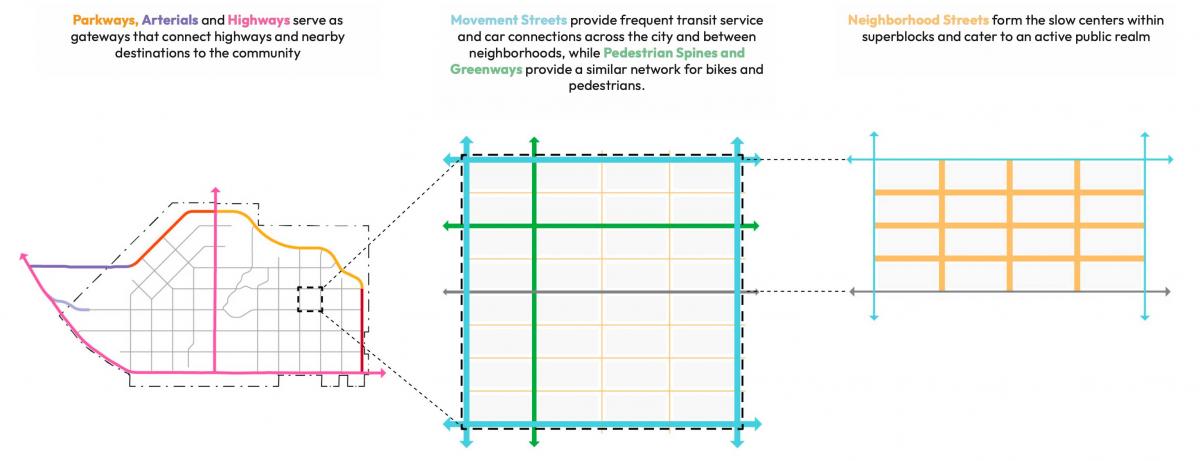

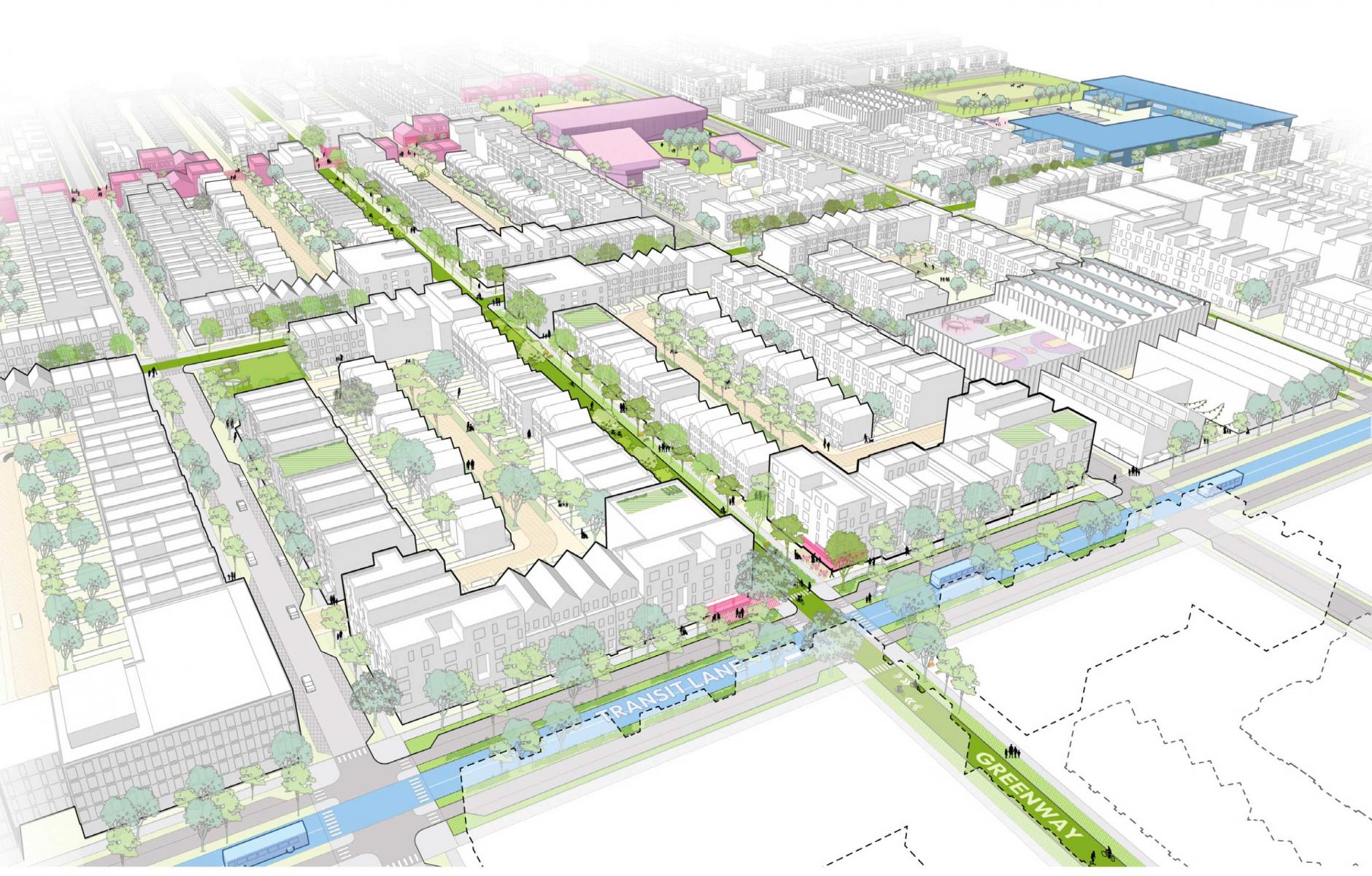

CNU cofounder Andres Duany, who was interviewed for this article, calls the California Forever plan “terrific” and “very advanced. … The grid is very sophisticated,” Duany described the plan as a “tartan grid,” with A, B, and C types woven together. These include higher-traffic “movement streets,” slow neighborhood streets with light traffic, and greenways that don't allow cars—but are fronted by buildings—creating long bicycle corridors throughout the city.

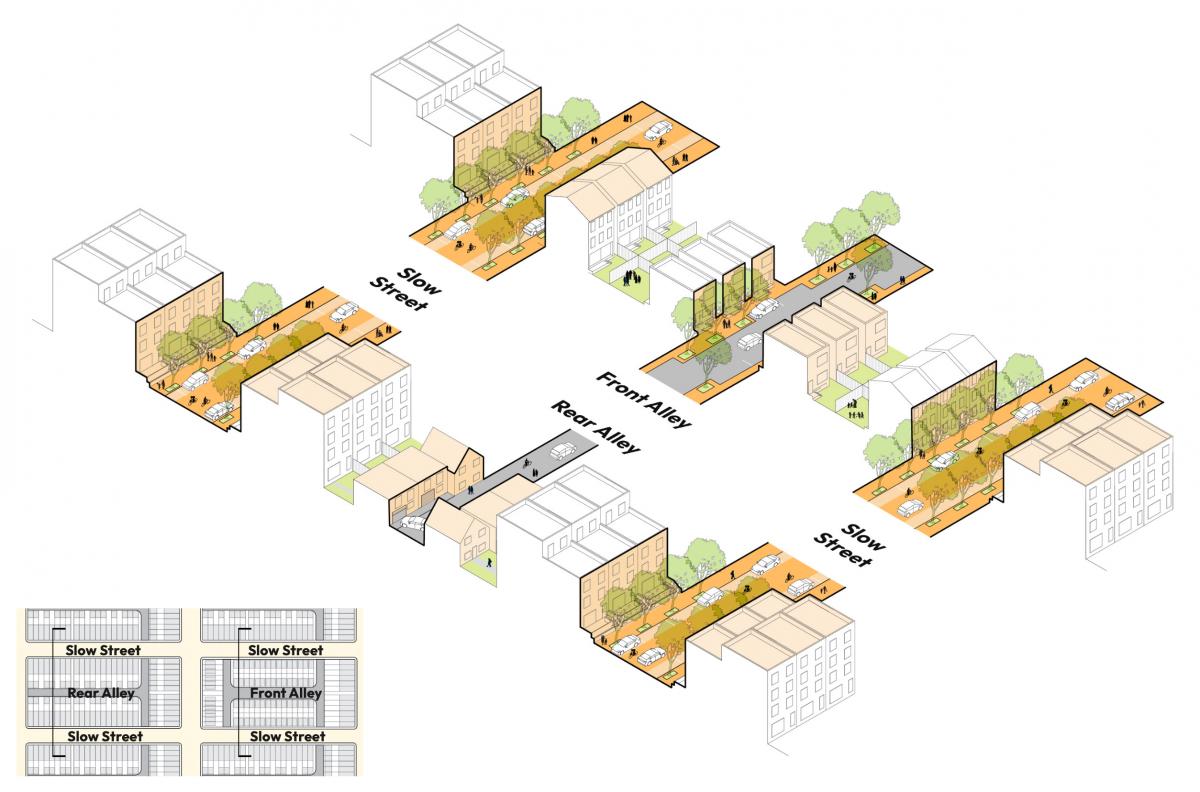

The movement streets will be designed as boulevards, with four rows of trees and dedicated Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) lanes in the middle. None of these types, including movement streets, will have more than one lane of automobile traffic in each direction—making them crossable for pedestrians and bicyclists.

Within blocks, another layer of mobility is provided by rear alleys, which face outbuildings, “front alleys,” which are mews with small homes, and pedestrian pathways. The mews are innovative and provide a setting for lower-cost housing, Duany says. "That's very interesting to have a layer of much more affordable housing, within the block, as in New Town Edinburgh," a historic part of the Scottish capital, he notes.

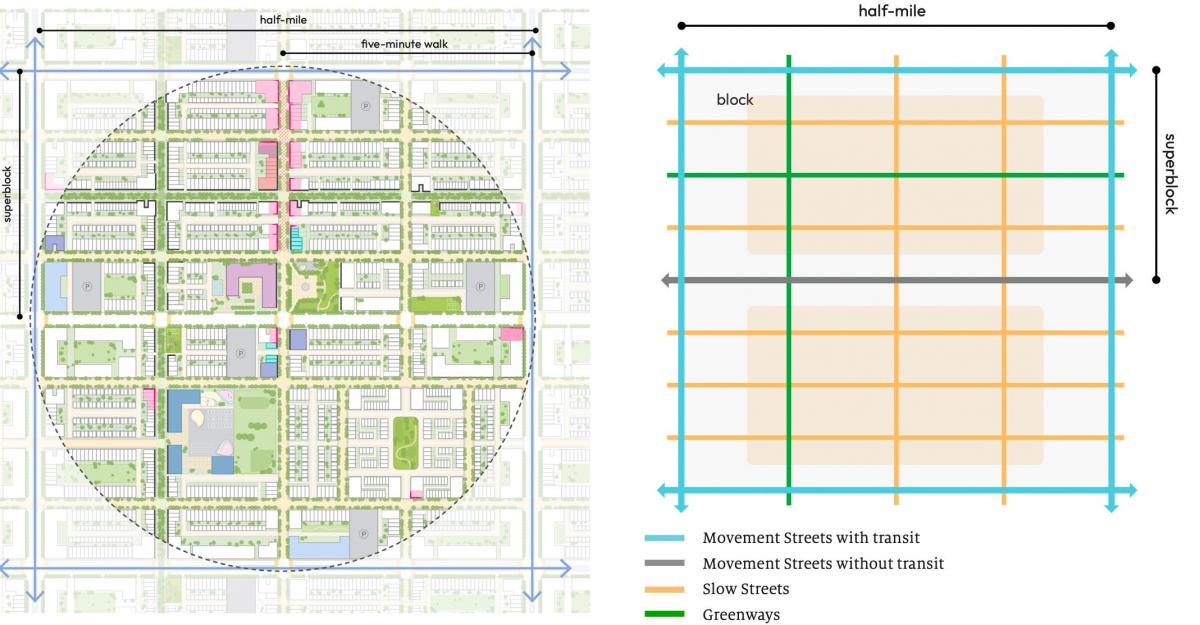

Each street category has subtypes, for a total of 15 street types. The grid is geometrically rigid, but flexible, Duany says, "taking advantage of its rigidity to make it functional.” Cleverly, the planners are using the end caps of the long, thin blocks to add density with apartment buildings up to 85 feet tall.

The entire plan is based on a standard-sized block, 280 feet by 600 feet, which is the dimension of typical Chicago blocks. Why Chicago? “It’s those rowhouse neighborhoods,” Metcalf says. “They have held their values for centuries, incredibly resilient and adaptable. It’s also subjective—it’s among our favorite places.”

It’s also a geometry that fits neatly inside a Jeffersonian grid. Four block lengths or eight block widths is a half mile. So, 32 blocks make a 160-acre neighborhood that is a five-minute walk from center to edge. With that basic block dimension, the planners can create any number of variations by adding greens or combining blocks for special uses or different housing arrangements.

Planning a project of this size allows California Forever to take unusual steps, such as proposing a major new transit system. The technology is BRT, which avoids the expense of rail infrastructure. The BRT would run on dedicated lanes on the boulevards, with lines a half-mile apart, east-west and north-south. The east-west lines will run directly through the Solano Foundry, a 3.5-square-mile industrial park on the west end of the city. Duany believes the half-mile spacing may constitute too much BRT for the city, but that switching to autonomous vehicles could make the system work.

Unlike most city bus systems, the California Forever lines will be absolutely straight. That geometry and the dedicated lanes are designed to make this system efficient. Some of the lines will run through downtown and district centers. The BRT lanes will be designed for emergency access, enabling fire trucks and ambulances to respond to calls if the streets become congested.

The BRT lines will terminate in parking garages, encouraging visitors not to drive through the city. The minimum parking requirements will be zero, Metcalf told CNU. “There is, by no means, enough parking,” Duany says. “That means they really are committed" to reducing automobile use.

The specific plan encompasses 24 square miles, including a greenbelt that surrounds the city. That amounts to 16,600 people per square mile—a density that is midway between Boston and San Francisco. Other notable features include:

- The 2,100-acre, 40 million-square-foot manufacturing and technology Solano Foundry is planned on a grid, connected to the rest of the city by BRT, bicycle, and small electric-vehicle networks. This area is restricted to commercial use because of the flight paths of nearby Travis Air Force Base. Since no housing is allowed, there will be no conflict with residents and plenty of room for businesses to grow. Block sizes will be flexible, allowing nearly any lot size to accommodate business needs. California Forever is also exploring building a 1,400-acre shipbuilding facility at the mouth of the Sacramento River, just to the south.

- In the middle of the proposed city, the plan shows an open-space corridor called Central Park that stretches for about four miles, southwest to northeast, along a stream corridor. About a half mile wide, the park connects to downtown and to the south and north greenbelts, part of the ring of open space proposed to surround the city. All residents will live within 1.5 miles of these green corridors, providing access to active transportation and recreation. Central Park will also be a site for cultural facilities like performing arts.

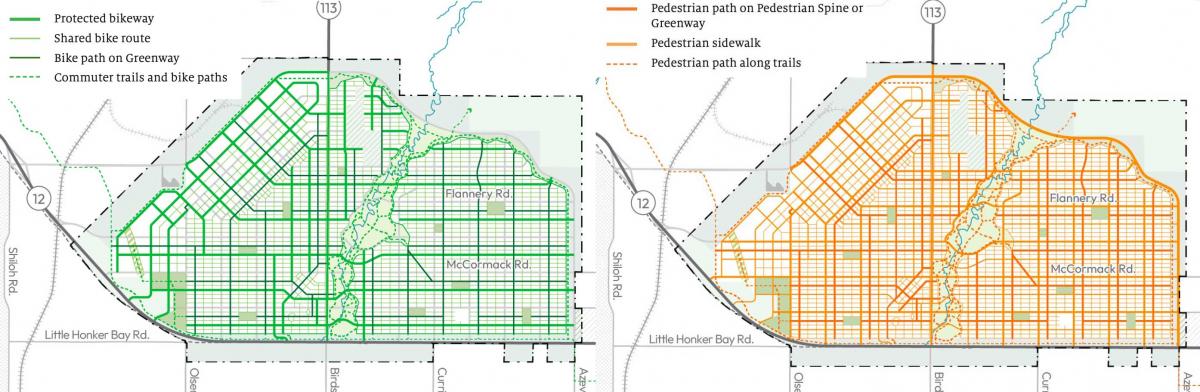

- A dense network of bicycle, e-bike, and neighborhood electric vehicle paths, protected lanes, and shared streets is planned throughout the city.

- Two “Maker Districts” are proposed, based on historic warehouse districts, to feature nightlife and entertainment in addition to light manufacturing, commercial spaces, and housing. One of the Maker Districts connects downtown to the Foundry, creating a mixed-use transitional area.

- A large downtown area and two urban centers are planned, where social activities such as live music, dining, festivals, fairs, and other events will be concentrated. These centers will offer sites for civic buildings, offices, and service employment.

- The Pedestrian Spine is a pedestrian-only corridor (no cars or bikes), intended to become “Downtown's premier pedestrian destination.” It will have outdoor cafes and mixed-use. Despite being narrow, it will have substantial pedestrian capacity—a good place for special events.

- Housing will focus on row houses and mid-rise apartments. Starter row houses and row houses with accessory dwelling units are variations on the row house type.

- The planners make efficient use of the land and the streets. The building types, apartment buildings and row houses, come out to the sidewalk. Designers also keep the streets tight. The bicycle network is dense, but selectively placed. For example, streets with transit do not have bike lanes, which allows the boulevard "movement streets" to be 100 feet wide, building-to-building. The neighborhood streets are 56 feet across, building-to-building. That approach adds to street enclosure and real estate productivity.

California Forever proposes a radically different form of development at this scale compared to what has been built since the middle of the last century. But the developers believe the market will support this project. “A large part of our employer-attraction thesis is that there is an underserved market for a place where companies can grow within the broader Bay Area without facing uncertainty about future approvals. Employers need a place where they know they are not just getting an approval to build one facility–they need to know this is a place where they can grow for years to come.

“On the residential side, we believe there is an underserved market for walkable urbanism designed for people of all types, income levels, ages, and family situations.”

In-house planners and a team of consultants are designing California Forever. Consultants have included SITELAB urban studio (urban design), CMG (landscape architecture), Fehr & Peers (transportation), ENGEO (geotech and hazmat), CBG (civil engineering), and EKI (water).

The question is whether it can be approved. Professors Chris Elmendorf, UC Davis-law, and Ed Glaeser, Harvard-economics, cited the major obstacles to getting shovels in the ground in a Los Angeles Times piece this week. “At a minimum, the California Forever project will require approvals from one city (Suisun), one county (Solano) and eventually one state agency (the California State Water Resources Control Board). Each approval triggers review under the California Environmental Quality Act and potentially years of litigation and delay. A Solano County supervisor has already told California Forever, ‘Go somewhere else.’ If she persuades two of her colleagues, the project is dead.”

Glaeser and Elmendorf criticize the regulatory roadblocks today that stand in the way of building a new city or housing production in general—especially in California. They argue that a new state-level process should be established to streamline permitting for urban development projects of statewide significance. That may or may not be good policy, but I wouldn't count on any such radical change allowing this project to move forward. Yet the writers are right that, if approved, the plan would be an important experiment in city building.

The project would nearly double Solano County's population, occupying only 3.5 percent of the land. It would take 40 years to build out, and we could learn as it grows. California Forever's models predict that the city will achieve the lowest vehicle miles traveled of any city in America, save New York. As we face climate change, that hypothesis warrants testing.

The professors, however, are more interested in productivity than the environment, calling the project "an audacious effort to operationalize the last 30 years of research in urban economics.” That research shows that “packing more people and businesses into a small geographic area makes everyone more productive. People who live and work close together learn from each other,” they explain.

They also claim that California Forever is “unlike anything the United States has seen before: exurban in location, intensely urban by design.” I take issue with that statement because when the Manhattan grid was surveyed in 1811, the streets were laid out through fields and farmhouses. Although the term exurban had not yet been invented, those early grids were designed in rural areas. Make no mistake—we have done this before.

The project faces daunting challenges to approval that the original developers of the Chicago block never contended with. And yet, if the project is approved and still looks like the current plan—two big ifs—California Forever could be a model for how to develop in other cities and towns.

For one thing, California Forever circumvents the problem of traffic engineers by using a street grid of two-lane streets. This would be an opportunity to demonstrate, in modern times, the efficacy of a street grid laid out over a large area, with dispersed traffic that accommodates multimodal travel across a city, strengthened by comprehensive transit service and incentives for alternative transportation.

Such a project could foster a new mindset that enables mass urbanism again, making urbanism the default option rather than a niche, restoring an approach that served the country well for its first 175 years.

Note: I welcome comments on this article or California Forever. There are many perspectives on this project. Please write in the comments what I missed, or email me at rsteuteville@cnu.org.