Six urban center types transforming cities

Jonathan Barnett has been at the forefront of urban planning for an astonishingly long time. From 1967 to 1971, Barnett was director of urban design for New York City’s Department of City Planning under reform Mayor John Lindsay. Over the last half-century, he has held long tenures as a professor at the City College of New York and the University of Pennsylvania, where he is now an emeritus Professor of Practice in City and Regional Planning.

During that time, he has maintained an urban planning practice, written books, and served on the board of the Congress for the New Urbanism from 1995 to 2005. Along with Vincent Scully and Robert Fishman, his presentation kicked off the first CNU Congress in 1993, providing a foundation for the discussions that launched the movement.

His new book, Redesigning Urban Centers: Adapting to Changing Real Estate Markets, reveals that Barnett is still a sharp and knowledgeable analyst of cities. In it, he draws on his two biggest strengths: a unique vision of how cities and their regions function as a whole and a long view of how cities are changing, including history that he witnessed firsthand.

Christopher Leinberger, America’s pre-eminent researcher of walkable urban development, calls Redesigning Urban Centers “the best book about the future of US metropolitan areas yet written.” Even taking into account back-cover hyperbole, that’s high praise.

Using the Philadelphia region as an example, Barnett has identified and described how US cities are changing in historic ways today. The book focuses on six types of urban centers getting significant investment: reimagined downtowns, innovation districts, edge cities becoming real cities, suburban shopping streets turning into mixed-use centers, urban districts near airports, and the cautionary tale of bypassed downtowns relying on government support.

I closely follow these trends, and I learned a great deal from reading Redesigning Urban Centers. Overall, the book offers an optimistic view of urban development today, bolstered by data and analysis of real places. I had assumed that, in this decade, sprawl had resumed at a torrid pace, but apparently building on the fringe is less profitable than it once was: “The demand for urbanizing land also seems to have stabilized at about one-quarter of its peak in the late 1990s,” Barnett explains.

“Instead, developers began seeing opportunities in disused industrial sites, failing office parks, and empty shopping malls, as well as vacant blocks and buildings in older urban centers,” he writes. Sure, new houses are being built in the suburbs of Philadelphia. But the city and region are experiencing the most significant and dramatic investments on infill sites—both urban and suburban. Similar types of investments are occurring across America. New urban centers being developed today are unlike the downtowns you see in old photographs or the suburban malls and office parks of the late 20th Century, he says. What do they have in common? They need “place management” to be competitive, and they must overcome outdated zoning regulations.

Legacy downtowns

Philadelphia’s Center City experienced a period of decline in the 1960s through 1980s, losing ground to suburban shopping malls and office parks. Declining city revenues created a downward spiral of services, which drove investment out. However, the city retained its appeal and assets, such as cultural institutions, historic architecture, walkability, and densely populated nearby neighborhoods, which the suburbs and poor planning could never fully extinguish.

The assets were waiting for a resurgence, which began with the 1990 establishment of the Center City District, covering 233 blocks and almost 1,700 properties at the commercial core of the City. With a special assessment on real estate (now at about $0.13 per square foot), the business improvement district (BID) was able to achieve what the city and police alone could not—a clean and safe downtown.

The BID paid for sidewalk cleaning and ambassadors who worked with police to discourage crime. The District also paid for some iconic public space improvements, such as special lighting and facade illuminations on South Broad Street, dubbed the “Avenue of the Arts,” making that streetscape exciting for attendees of regional performing arts events. The District also designed and built Dilworth Park next to City Hall, likely the spot in the city with the highest foot traffic, attracting a reported 11.5 million visitors annually.

The BID also sponsors programming of public spaces. Everything the District does is focused on improving the public realm, which in term draws visitors, new residents, and investment downtown. Many factors have contributed to the revival of Center City, which has benefited from the development of 36,000 housing units and a substantial increase in employment. The area has also recovered from losses incurred due to the pandemic and civil unrest in 2020. Barnett takes us through all of the factors, but through it all, the Center City District BID has been the catalyst.

Innovation districts

A robust economic engine has emerged across the Schuylkill River from Center City, in the University City area of West Philadelphia. The site of the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University, and a world-class medical district, a BID called the University City District plays an important role here.

This center of research and innovation has its roots in the 1963 founding of the University City Science Center, an offshoot of Penn. That decision led the university’s transformation from “a respected regional institution into a national research university with worldwide influence,” Barnett reports. The District specializes in health sciences and related cutting-edge technologies, a growing part of our economy.

Health sciences professionals work in labs, offices, or hospital settings, which means that in urban locations they take transit, support restaurants and establishments at lunch and after work, and frequently live in nearby neighborhoods. They also benefit from the presence of research universities, such as Penn and Drexel. Biological sciences, in other words, support walkable urban places like University City.

The BID, meanwhile, serves a similar purpose as the Center City District, in maintaining a clean and safe public realm with urban amenities. The University City District built its own version of Dilworth Park—The Porch in front of 30th Street Station, one of the busiest rail stations in the US. The Porch is a great place to hang out, offering a variety of attractions and regularly hosting public events.

Consequently, University City has become a second downtown for Philadelphia, with a growing skyline and strong employment base.

From edge city to downtown

King of Prussia is an edge city in the northwest quadrant of Philly’s metropolitan region, Barnett reports. It is located at the juncture of four major highways in the region’s “favored quarter,” a typical edge city location. With the third-largest mall complex in the US, substantial industrial/office concentrations, little public transit, and major automobile traffic, the area is economically comparable to a city. From a physical standpoint, it is a mess.

The King of Prussia business improvement district “seeks to integrate the separate land uses and retrofit the area with new attractions, improved public spaces, and better pedestrian and transit connections,” Barnett writes. King of Prussia has a long way to go before it resembles a genuine downtown, but strides forward have been made in several important respects.

First, a 132-acre site adjacent to (although across a highway) from the mall complex became available for redevelopment. A developer purchased the site of a former golf course and, after battles with the township, received court approval to build a mixed-use development on a walkable street grid. The Village at Valley Forge has been under development since 2012.

Also, a formerly single-use business park to the north of the mall, Moore Park, received zoning approval to become a mixed-use district. In that area, the King of Prussia District has built the First Avenue Linear Park, a landscaped pedestrian route about a mile and a half long, connecting 15 separate large properties, Barnett reports. That’s the first step in creating multimodal access in an area that was planned entirely for automotive travel.

The mall itself has been proposed for some mixed-use redevelopment, but this would require a zoning change and plans never moved forward after the pandemic. However, the right pieces falling together “could eventually make it a highly urban location,” Barnett writes.

Another problem that is yet to be solved: Providing the area with better transit access.

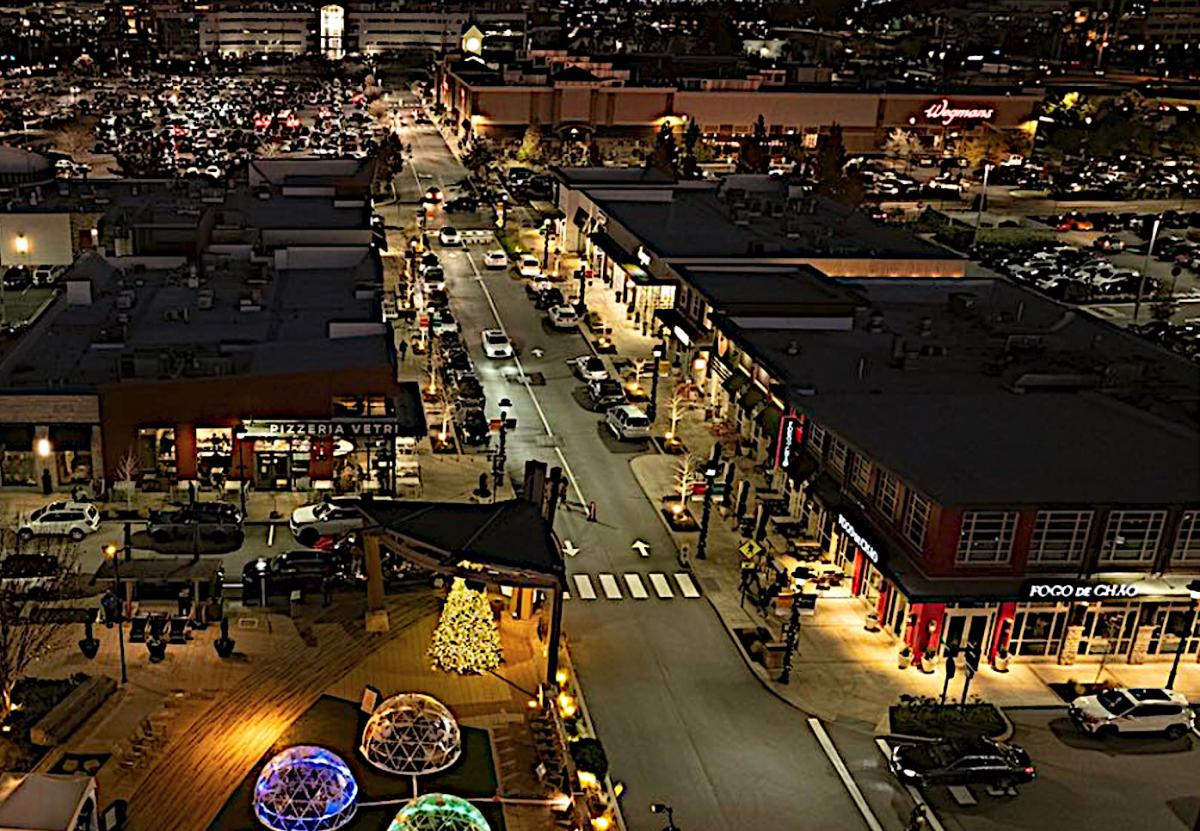

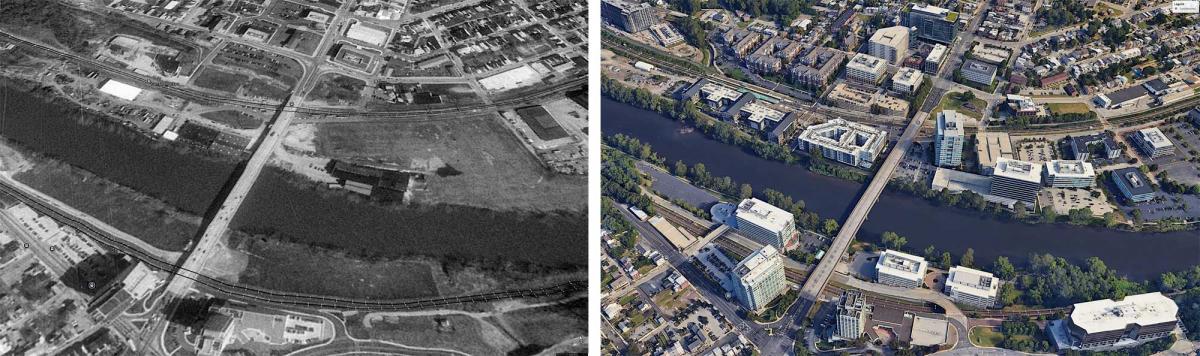

Suburban shopping streets to urban centers

Barnett provides two examples of this type. The first, Conshohocken, was a “sleepy borough in Montgomery County” that lost its industrial base. Industrial lands on the river have been transformed over the last three decades into a walkable, transit-served “regional office center with high-density residential development.” The nearby blocks of a local main street have become “a thriving restaurant destination.” The amount of development that has taken place is astonishing. The area needs no BID, Barnett reports, because the borough is so small that local government can pay close attention to the needs of the businesses.

The second example, Ardmore, is at the center of a prosperous Main Line suburb, was not immune to the competition from malls and big box stores, but it never went through crises of say, Conshohocken. Yet place management and new residential and commercial development in recent decades has made it more of a complete downtown. “Ardmore has a business improvement district chartered by Lower Merion Township to manage its historic main street and build its identity of place,” he writes. Across the tracks, a mixed-use developer has purchased a historic open-air shopping center with more mixed-use in a downtown format.

Development near airports

“The Philadelphia Airport, which already has adjacent hotels and warehouse buildings, is becoming what some scholars call an aerotropolis because of redevelopment” on nearby properties. This is one of the more interesting case studies that has emerged in recent years due to opportunities on huge former industrial sites. In particular, the Bellwether District is planned on the site of the former Sunoco oil refinery—more than a thousand acres that has been cleaned up of pollution near where the Schuylkill flows into the Delaware River.

That allows for a 700-acre warehouse district geared to air freight to be built—a growing economic type that is underserved—in addition to a 250-acre innovation district about a mile away from the life sciences hub at University City.

But that’s not all—a third downtown (after Center City and University City) is being built on the redeveloped site of the Philadelphia Navy Yard, immediately upriver from the airport. Now known as the Navy Yard, it remains the site of substantial ship construction by a private firm, and the Navy continues to have operations there. However, it is now a major employment center for office and light industrial firms, with residential development underway.

Still another urban center is planned in the vicinity, on the massive parking lots of the city’s sports and entertainment venue district just to the north of the Navy Yard. At the center of these three sites, which each will likely receive billions in private investment, is a 350-acre Olmsted-designed green space, Franklin Roosevelt Park.

Bypassed downtowns

Amid these positive urban trends, Barnett inserts a cautionary tale. Camden, New Jersey, directly across the Delaware from Center City, has a great location and excellent transit connections with two major lines. It has a university campus, a major hospital, a Fortune 500 headquarters (Campbell’s soup), and decades of economic development. And yet, Camden is a long way from becoming a viable, self-sustaining urban center. Camden is a type of former industrial city (East St. Louis, Illinois, Gary, Indiana, and Bridgeport, Connecticut are other examples) that has fallen so far that it will need continued government subsidy long into the future. In Camden’s case, the redevelopment efforts along the waterfront, in the old downtown, and in college and medical campuses are too far apart: They have yet to coalesce into a whole with economic momentum.

These case studies are not unique. The Philadelphia area has 150 urban centers, as identified by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission. Main Street programs are operated in 1,200 communities nationwide where a local management organization, under Main Street America principles, runs a place-based program to keep the area clean, safe, and vibrant. In the final chapter, Barnett identifies new examples from around the US where edge cities are being converted to downtowns, innovation districts are under construction, and similar transformations are underway.