Modeling Missing Middle across an unaffordable region

Cape Cod, with its iconic New England character and over 500 miles of coastline, faces a housing crisis that threatens year-round residents who provide the workforce to keep the economy going. Since 2000, many year-round houses have been converted to second homes for vacationers. Cape Cod workers, with a median income of $67,000, are routinely outbid by second homebuyers—70 percent of whom make more than $100,000 per year. That situation has resulted in continually rising median house values, while wages for workers do not keep pace.

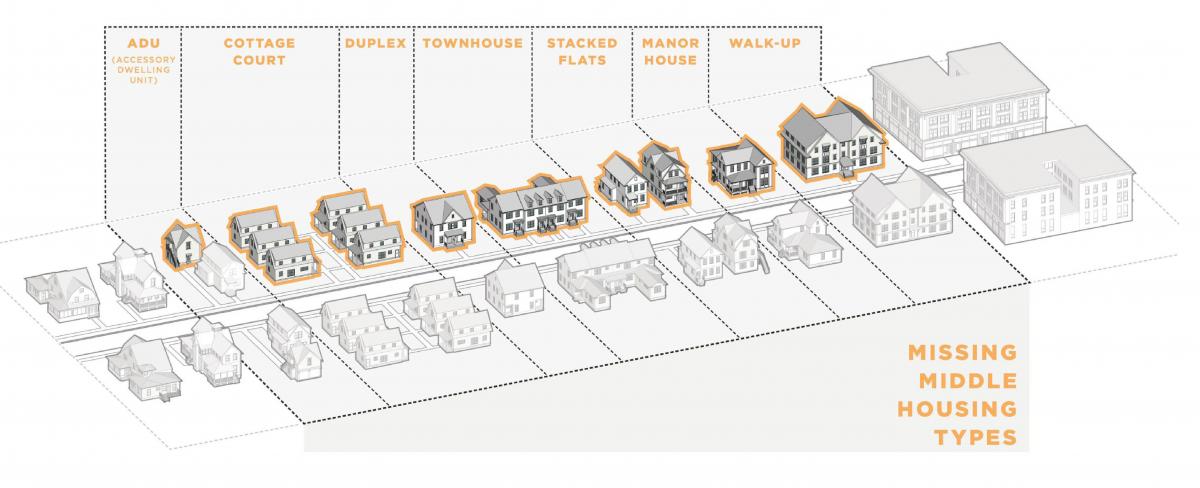

The Cape’s housing stock is overwhelmingly—82 percent—detached single-family homes. Those houses typically occupy 2-4 units per acre. The potential for Missing Middle housing, at five times the standard density, to ease the housing shortage is substantial, according to the report Cape Cod Resiliency: Missing Middle, which won a Charter Award this year for Union Studio Architecture & Community Design.

The research emerged out of a partnership of the design firm, the Cape Cod Commission planning agency, and five Cape towns “to demonstrate how traditional neighborhood patterns could address contemporary housing challenges while preserving the region's distinctive character,” explains Union Studio. “The project began with extensive documentation of the Cape's historical development patterns and existing Missing Middle housing types—the duplexes, townhouses, and small apartment buildings that already contribute to the region's most beloved village centers.”

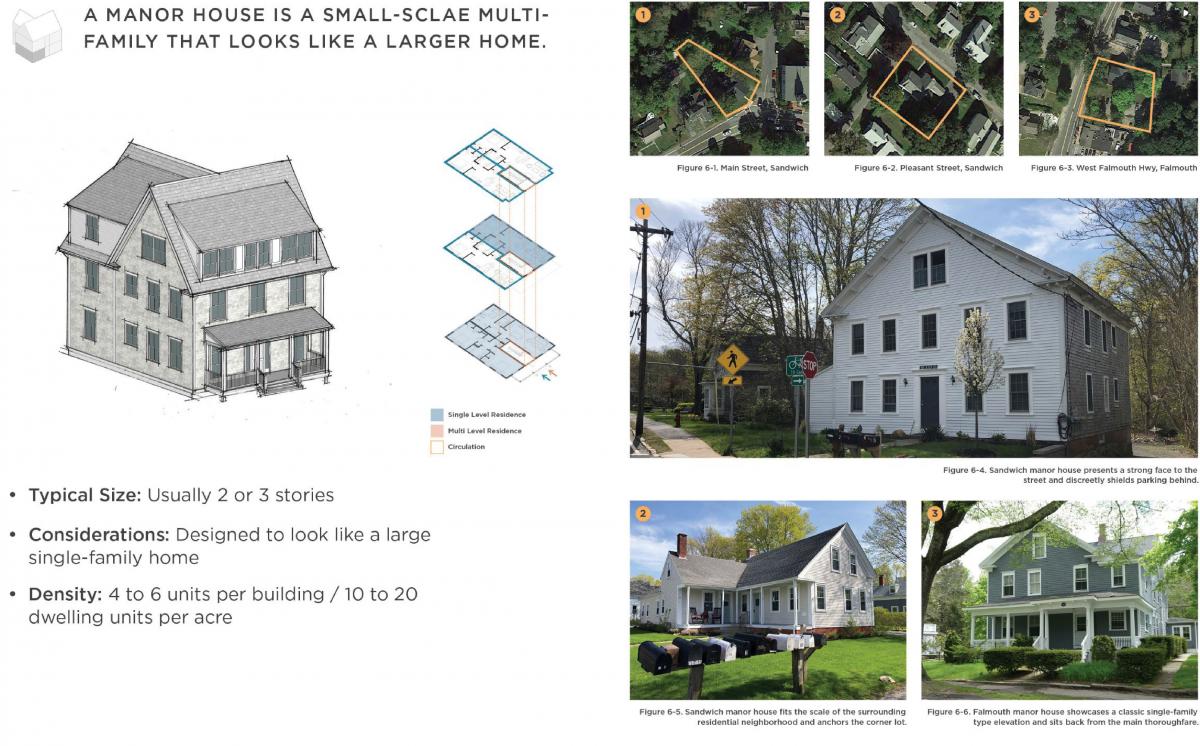

Community engagement was central to the process. For example, Missing Middle height preferences were surveyed. In the Upper Cape, Mid-Cape, and Lower Cape, which contain most of the population, the community accepts 1.5 to 2.5 stories. The more sparsely populated Outer Cape prefers 1-2 stories. Cape residents are generally not comfortable with 3-story or taller buildings. But even 1.5-2.5 stories of Missing Middle can generate substantial density—i.e., 20 units per acre in some configurations—comparable to a mid-sized 3-story apartment building. “Rather than presenting density as an abstract concept, local precedents demonstrated how traditional building types could provide needed housing while reinforcing neighborhood character,” the authors note.

The Cape Cod Resiliency project cost of $450,000 was funded through a state housing grant. “This investment has already catalyzed multiple implementation projects and policy changes that will have lasting impacts on the region's housing supply and affordability,” the planning team notes. Three demonstration projects under construction show how traditional patterns can be adapted to contemporary needs. The project:

- Promotes strategic infill over peripheral expansion of low-density housing. The infill and redevelopment focus enables housing in walkable locations with access to transportation networks.

- Addresses Cape Cod’s critical need for diverse housing types and price levels. The report shows how Missing Middle can provide variety for underserved markets like young adults and the elderly.

- Exposes current zoning limitations and provides a framework for zoning reform. Two towns adopted form-based code overlays that enable Missing Middle development while ensuring contextual design.

The design phase translated research insights into detailed designs for each town, showing how the Missing Middle can be woven into existing neighborhoods. In Falmouth, the town wants to add low-rise, moderate-density housing to a mile-long commercial strip on Route 28, a state highway that traverses the most populated areas of the Cape.

The design adds a roundabout to slow traffic on the commercial strip and replaces a parking lot with two short streets of duplexes, townhouses, stacked flats, “manor houses,” and mixed-use and residential walk-ups. The single-use, big-box site becomes 52 units of housing at 20 units per acre, while still retaining 4,500 square feet of retail. The range of small-scale housing fits into the context of a residential neighborhood to the south, smoothing out an abrupt transition from single-family to high-intensity commercial core.

Retrofit of similar sites typically envisions large mixed-use and residential buildings. The Falmouth model cleverly combines suburban retrofit with the Missing Middle, while achieving a density that could support transit and justify a site conversion. Cape Cod Resiliency examines suburban retrofit in addition to infill sites in the Cape’s historic villages, using traditional types like the manor house.

“This project allowed us to demonstrate to our community that context-appropriate missing middle housing can help us meet the region’s critical housing needs by adding density while complementing and enhancing the unique character of the Cape,” according to Kristy Senatori, Executive Director of the Cape Cod Commission.

The 2025 Charter Awards will be presented at CNU33 in Providence, Rhode Island, on June 12.

Cape Cod Resiliency: Missing Middle, Cape Cod, Massachusetts:

- Union Studio Architecture & Community Design, Principal firm

- Cape Cod Commission, Regional land use planning, economic development, and regulatory agency

2025 CNU Charter Awards Jury

- Rico Quirindongo (chair), Director, City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development

- Majora Carter, CEO of Majora Carter Group in the Bronx, New York City

- Jake Day, Maryland Secretary of Housing and Community Development

- Anne Fairfax, Principal, Fairfax & Sammons in New York, NY, and Palm Beach, FL

- Eric Kronberg, Principal, Kronberg Urbanists + Architects in Atlanta, GA

- Steven Lewis, Principal, ZGF Architects in Greater Los Angeles, CA

- Donna Moodie, Chief Impact Officer, Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle

- Joe Nickol, Principal, Yard & Company in Cincinnati, OH