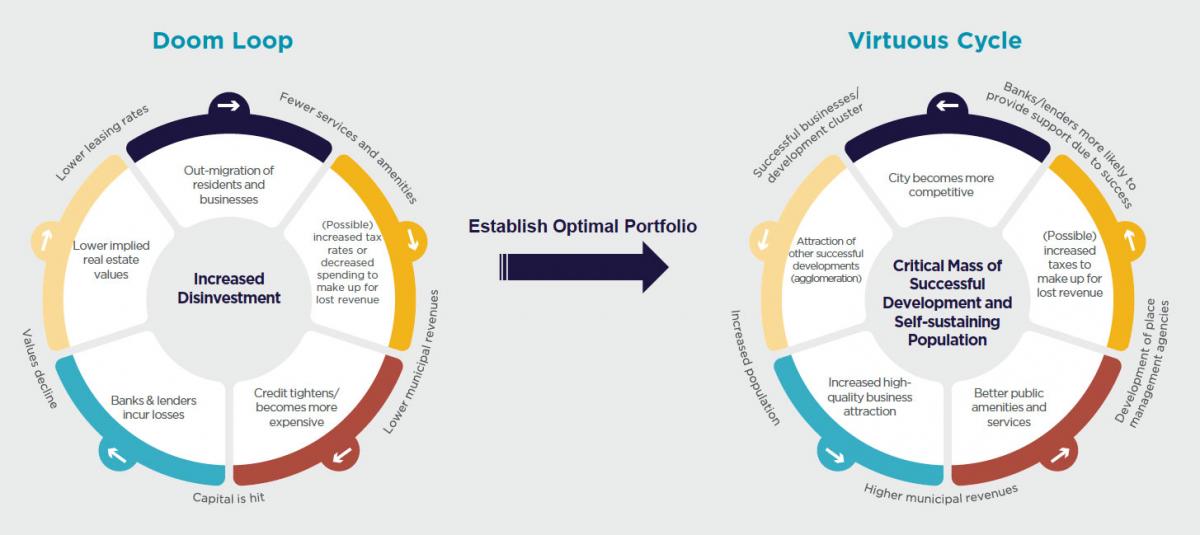

Office space conversion could lead to a virtuous cycle for cities

Cities need to “get real” and promote office building conversions to live- and play-oriented uses to avoid a structural “doom loop,” Christopher Leinberger and Rebecca Rockey told CNU’s On the Park Bench participants.

The good news is that downtown office conversions are feasible in two ways: 1) The low-hanging fruit of small-floor-plate, often historic, office buildings are more easily transformed into housing and other uses; 2) The declining value of more difficult conversions will overcome barriers. “If those offices are trading at 30 cents on the dollar, 20 cents on the dollar, the lowest I have seen is 5 cents on the dollar, you are effectively getting the building for almost free. There’s a lot you can do at those prices,” says Leinberger, cofounder of Places Platform and Arcadia Land Company.

Rockey, an economist with Cushman & Wakefield, and Leinberger are authors of a new report, Reimagining Cities: Disrupting the Urban Doom Loop. They cited difficult but successful conversions, such as a rectangular DC building converted to “capital E” shape, which “exploded in demand,” and a downtown Manhattan building where a hole was cut through the middle to bring light and air to the interior structure.

They said cities need to incentivize conversions through zoning code reform and expedited permitting, yet declining tax valuations have not caught up with dropping real estate values for office. Because assessed tax values are behind the times, officials have not fully accepted that the office market is in retreat, and this trend will continue until urban real estate portfolios become more diverse and balanced. This is especially true in major “gateway” cities like Boston, San Francisco, and DC, where 85 percent of the real estate is in office uses.

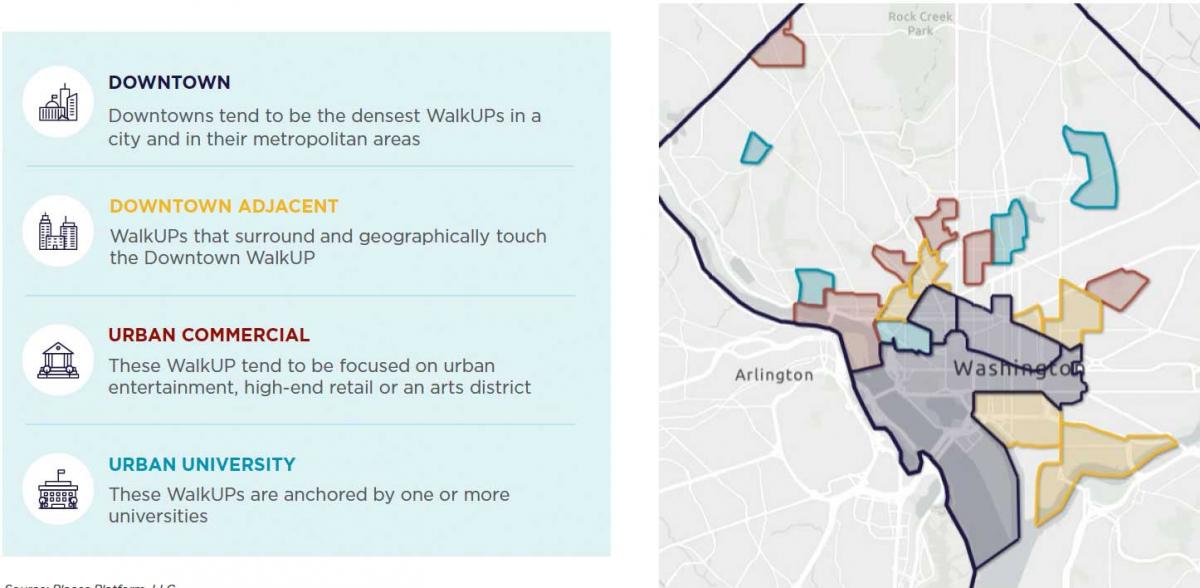

There is pent-up demand for walkable urban living, Leinberger and Rockey argue. Two major trends, the “knowledge economy” of technology and higher education and the “experience economy” of tourism and recreation favor walkable urban places. In regionally significant Walkable Urban Places (WalkUPs), cell-phone data shows that two-thirds of foot traffic is visitors who neither live nor work in the WalkUP. Buildings devoted to “play”—restaurants, retail, museums, performing arts facilities, convention centers, etc.—account for only 14 percent of real estate but drive much of the pedestrian activity and economy.

They say that nearly all cities would benefit from more “play” oriented real estate. The built environment also needs to be designed for walkability. Cities “The knowledge economy and the experience economy want to be in walkable urban places. That’s the reason for the price premium,” Leinberger explains.

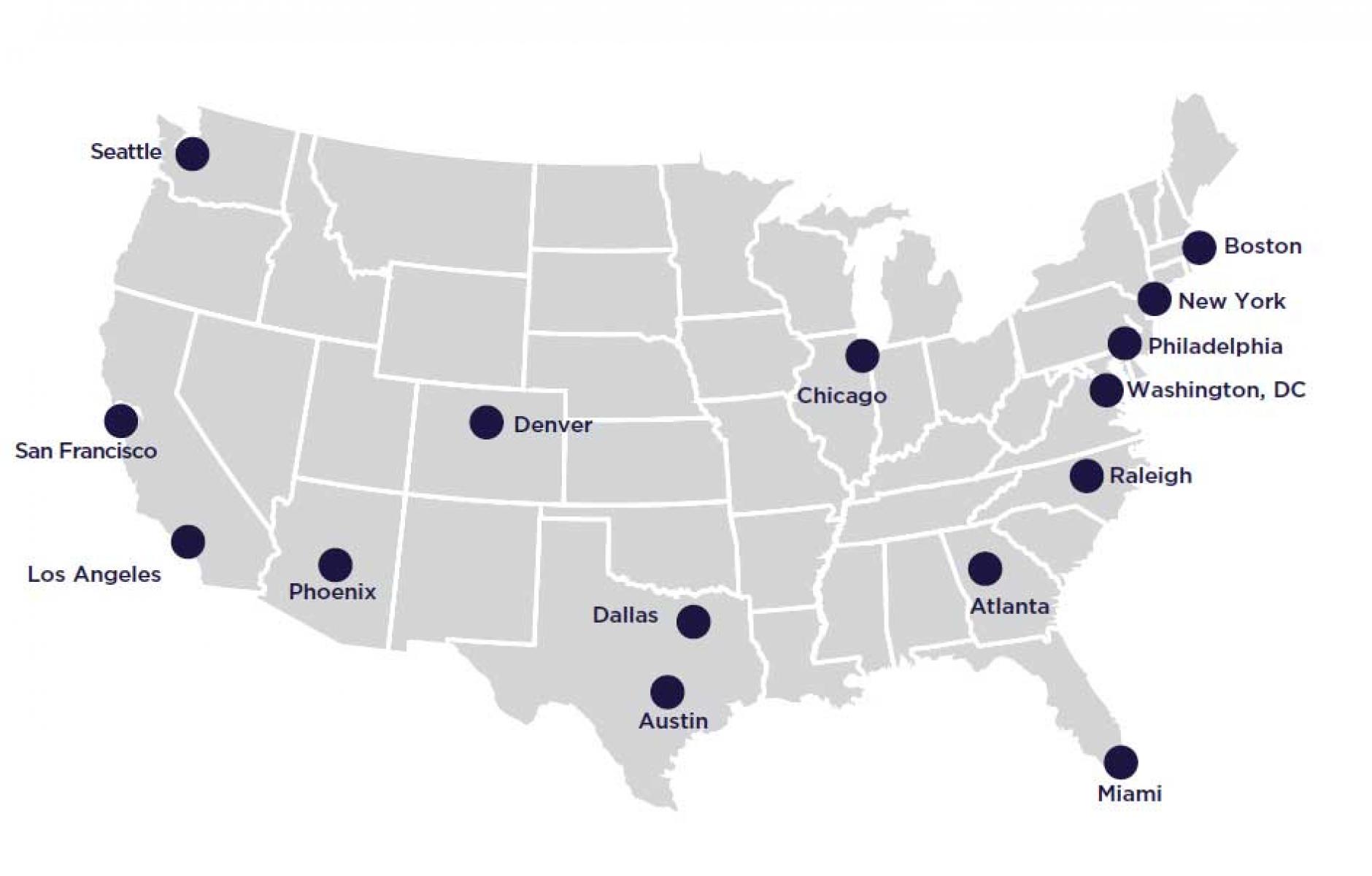

The report looked at 208 WalkUPs in 15 cities. Some cities are doing better than others. The downtowns of cities like Miami, Phoenix, Atlanta, and Raleigh have lower percentages of office space and are doing relatively well. Most cities studied have 60-85 percent office space downtown and are in a doom loop, however. The report applied portfolio theory to the real estate market in WalkUPs, and discovered the connection between a more balanced real estate portfolio and economic success. Because most cities put too many eggs in the office real estate basket, they were vulnerable during the pandemic.

If cities act decisively, they can save their downtowns and address the housing affordability issue. Leinberger attributes the affordability crisis to land costs. “Land has gone from 15 to 20 percent of what you buy when you buy a house or an apartment to 50 to 60 percent—in San Francisco, it's 80 percent.”

The answer is to greatly boost the supply of walkable urban housing, which currently makes up only 1.2 percent of metropolitan land in the US, he says. If that figure rose to 5 percent, it would “flood the market” with residential units and end the crisis, he says. We can do that by promoting housing conversions in the urban core and rezoning corridors leading out of cities for compact, mixed-use development.

If cities don’t act decisively, they risk seeing their urban center languish for decades. On the flip side, acting now would enable them to take advantage of a historic opportunity to reimagine their downtowns. The goal is to turn the current “doom loop” into a virtuous cycle, where change leads to better outcomes.

See the entire video.