Innovative village based on agrarian urbanism

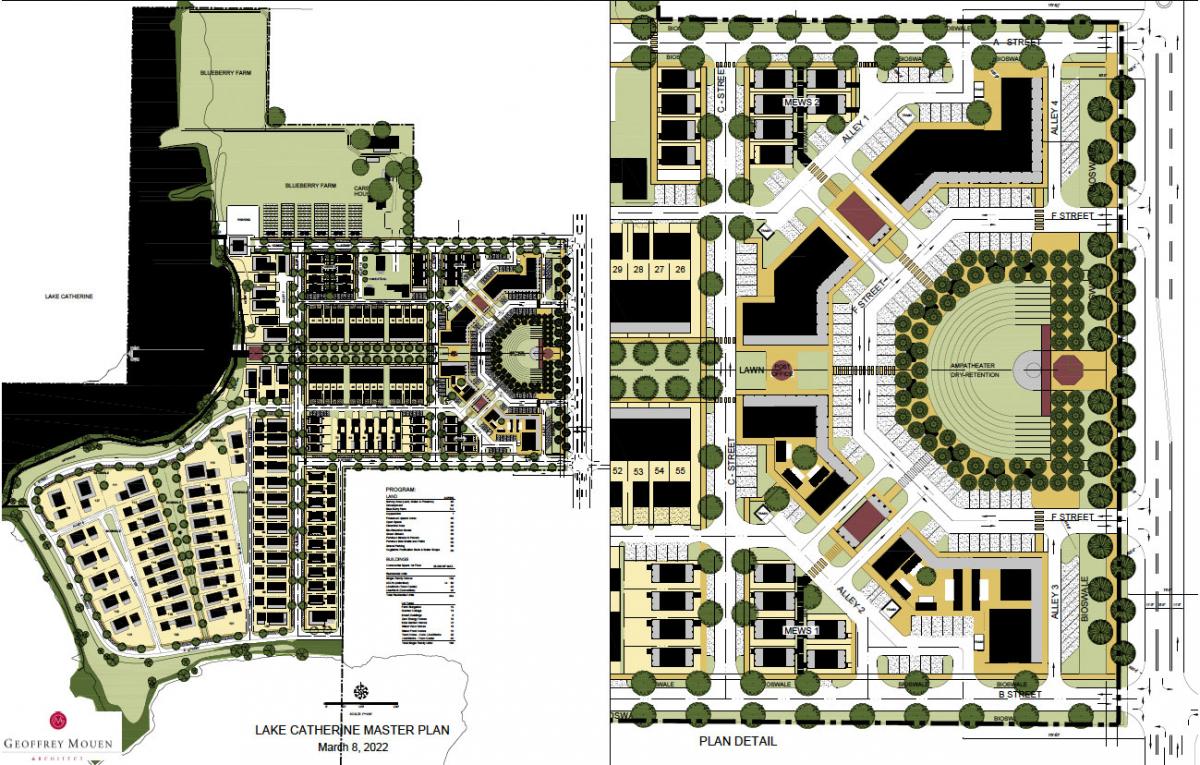

A blueberry farm in Groveland, Florida, has been designed for development as a village while maintaining current food production levels. The Lake Catherine Farms plan utilizes agrarian urbanism, where a mixed-use place maintains intensive agriculture on a portion of the land, while incorporating an agrarian lifestyle.

That contrasts with the typical builder practice of subdividing a farm into tract houses, obliterating agricultural traces on the land.

A mile north of downtown Groveland, the farm is currently an agriculture tourism draw, attracting visitors to pick blueberries, attend musical concerts, and dine at a restaurant. “The Lowe family is adamant about maintaining the agriculture history of the land going forward,” says architect and urbanist Geoffrey Mouen. The Lowes could have sold to a developer, but instead will continue to live and work on the property. “They told me, ‘we want to stay here, live on this land, cherish the land, and incorporate agrarian lifestyle into the design.’ It seems like a natural fit with the agricultural tourism that is going on,” Mouen explains.

The plan borrows much from the famous new urban town of Seaside, Florida, including the shape and proportions of the town square. A green space bounded by live-work townhouses is connected to the central square, much like Seaside’s Ruskin Square. The rest of the plan takes its own path.

The Lowes “went up to the Panhandle, we looked and walked around the town of Seaside, and a lightbulb went off," Mouen said. "They said 'this is exactly what we hoped we could do.’ ” Explains Dustin Lowe: “We don’t have a beach, but we have a lake, and tourism galore. It’s a natural fit.”

Notable aspects of the plan include an edible landscape (agrarian urbanism), the Seaside-like public spaces, a new architectural approach called “20-60-20,” incremental development using Light Imprint stormwater techniques, and the taming of a state highway using FDOT’s context-based street classification system.

Of the property’s 67 acres, 35 acres are usable for development. Eight will be set aside for the blueberry farm, including the greenhouses and open fields. Green streets, orchards, and the agrarian lifestyle will be incorporated into the village with an edible landscape.

The plan includes cottages, bungalows, and larger lakefront homes, in addition to the live-work units. Most houses will have the ability to add accessory dwellings. The town center includes 28,000 square feet of ground floor commercial, civic buildings, and apartments over retail. The first phase will have 2,000 square feet of commercial, 20 apartments above, and cottage homes. Design and engineering work is underway, with site work anticipated by the end of this year.

A city of 18,000, Groveland grew up around citrus farming—as the name implies. Downtown features a grid of streets laid out prior to 1950 but mostly built out in the second half of the 20th Century. The citrus industry around Groveland, and across Florida, has taken a huge hit in recent decades due to “The Greening,” a microscopic insect. That’s why the Lake Catherine farm switched to blueberries.

The Lowe family, with six generations on the land in Central Florida, will develop the innovative village under the city’s form-based code, adopted in 2020, while the family uses high-production aquaponic greenhouses on a portion of the site that will stay as a farm.

Seaside as a model

From a business perspective, Seaside’s six-sided square is an excellent model, with its strong visibility to passing traffic. The shape handles parking well. The head-in parking allows for approximately 100 spots at Lake Catherine that will not overwhelm the public space. (Seaside is now getting rid of its central square parking, but it has served the town well for four decades). The design creates a strong sense of place that will help slow traffic on Howey Road (Route 19).

If Seaside is any indication, the square will be popular as a hangout and performance space. A town hall, post office, and chapel are included in the plan, in addition to businesses with residences above. An arcade around the perimeter of the square, an architectural element borrowed from Seaside, provides shade in the Florida heat.

The town square will be 70 feet narrower than Seaside’s. Andres Duany, who along with Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk planned Seaside, has long claimed that the Seaside’s town center is too broad, and he would design it tighter today.

Just to the west of the square will be a narrow garden green based on Ruskin Square. That central spine will lead to a performance space and dock on Lake Catherine.

The 20-60-20 rule

The developers plan to follow a “20-60-20” rule of 20 percent custom signature architecture, 60 percent “plain-old good” architecture, and 20 percent experimental designs (i.e., the latest, coolest ideas that push the envelope for sustainable design). The concept was developed by new urbanist consultant Nathan Norris, who argues that places tend to be bland if everything is beautiful (or non-offensive.) More challenging designs must be included, yet not overwhelm the whole, to achieve an ideal range of design, he argues.

Although Norris observed a similar pattern in historic places—the rule has never been tried at a new community scale. Norris first proposed that 20 percent of the architecture should be unattractive, but was convinced by Duany to go for experimental instead. “The challenge and goal are to have a diversity and an evolution of architecture over time,” says Bret Jones, the land use attorney for the Lowes. The bulk of the architecture will be based on local vernacular. The primary design DNA is set by the farmstead, with its wood-frame buildings and eight-foot-deep porches where the family can sit and drink lemonade, says Lowe.

In part, the plan utilizes local vegetation and turf that can survive the Florida climate without much irrigation. Where watering is needed, for an edible landscape, cistern systems will be employed for dwellings and commercial space. Light Imprint stormwater drainage is part of the plan—including use of bioswales. Requirements are reduced for pipes, because in most cases the rainwater will seep directly into the ground. The first phase includes cottage courts with boardwalks instead of sidewalks. The civil engineer, Paul Crabtree, is reusing the drainage system from citrus groves that were abandoned decades ago due to blight.

The family is looking at developing the property slowly and incrementally. Not only in the construction of houses, but in fostering businesses also. The plan calls for little wood shacks, food trucks, and air streams, evolving into brick-and-mortar businesses.

The lakefront will highlight a long dock extending out into the water, for boating and fishing. The lakefront bordering the property will be parkland. A stage on the water will feature performances. The central square on Howey Road is envisioned with a bandshell. Performance space extends the tradition of musical programming that is already in place. A boardwalk will connect the town to a regional trail that is 22 miles long.

Taming the highway

Route 19, which carries truck traffic from Groveland to the turnpike in front of the central square, is a challenge. The two-lane highway carries 10,000 vehicles per day, and is subject to serious state roadway controls. Yet the Florida context-based classification system, adopted five years ago, offers a way to modify the highway in front of the mixed-use center, to slow traffic and make it more pedestrian friendly.

It’s a walkable context zone, based on form-based coding from the city. The development is planned as a village, which means that the design speed must drop for the area immediately in front of the center. The default design speed in walkable context zones is 25 mph—higher speeds must be justified. Lake Catherine will be a test of the state’s relatively new, innovative, context-based system, and the Lowes are working with noted new urbanist traffic engineer Rick Hall in dealings with FDOT.

The Orlando region already has two nationally recognized new urbanist projects—Baldwin Park, which redeveloped a former Naval Training Center, and Celebration, which was launched by Disney to much fanfare nearly three decades ago. The Orlando Business Journal compares the Lake Catherine project to these notable models. “The region's latest project to take on the new urbanist mantle — which emphasizes the principles of how cities and towns had been built in the past few centuries, particularly before the advent of cars when most people got around by foot — may yet put its own twist on the planning philosophy,” the publication recently wrote.

The success of New Urbanism is typically in proportion to the willingness developers to learn all aspects of building a community.

“The whole family is engaged,” Jones says. “They spend an hour talking about curb radii on just one street, how close the street trees should be planted, permeable pavers, boardwalk sidewalks versus gravel sidewalks and regular sidewalks. They are studying every detail.”

Adds Mouen: “It’s not very often that I come across people who care about a place enough that they are willing to learn so much.”

The Lowes started with a deep understanding of the power of an agrarian landscape. Clinton Lowe, father of Dustin, quotes a line from a Robert Frost poem, “The land was ours before we were the land’s,” from The Gift Outright.

“From a farmer’s perspective it is “We were the land’s before the land became ours,” he says. Based on the plan, the Lowes have no intention of giving up the land or abandoning the land’s claim on the family.

Editor's note: This article addresses CNU’s Strategic Plan goal of working to change codes and regulations blocking walkable urbanism.