Florida’s success with context-based street classification

Attempts to create walkable places become an order of magnitude more difficult when state-owned thoroughfares are involved. The laudable goal of creating a human-scale neighborhood may descend into a multiyear battle—sometimes won by planners, more often by the engineers—and the outcome is nearly always unsatisfactory. In such cases, planners and the state DOT appear to speak two entirely different languages.

From Florida, which may be the most automobile-dominated state, comes a system that allows the state DOT and planners to understand each other from the get-go—using the rural-to-urban Transect as a translator. The Florida Context Classification system has been successfully used since 2018 when the FDOT Design Manual (FDM) was adopted, according to Billy Hattaway with Fehr & Peers and DeWayne Carver of FDOT, who recently presented to CNU’s On the Park Bench.

Since adoption, context-based street classification is permeating the thinking at FDOT, finding its way into planning, traffic operations, and safety manuals. “This idea was not that hard for traffic engineers to get their heads around,” says Carver, who led the department’s complete streets program for many years. “I was honestly surprised at how quickly they adapted.”

Implementation is taking longer than anticipated, due to the three-year pandemic and rising costs that have impacted infrastructure improvements. Applying the system to thousands of miles of state roads is a huge task that still underway, note Hattaway and Carver, who together have many decades of experience with FDOT and in were involved in creating the design manual. The accurate mapping of the land-use context of DOT streets and roads enables more appropriate thoroughfare design based on context. Moreover, the system recognizes future context when the municipality adopts a plan and form-based code calling for a new urban, walkable place. The FDOT system directly translates to place types of form-based codes, which were pioneered in Florida and now are fairly common across the state. Take a look at the current conditions at an intersection in Woodville, Florida, and a future vision:

The existing context class shown is C2, which means a high-speed thoroughfare. The proposed classification is rural town, which is a main street environment. Every design detail changes.

Characteristic of existing context class, C2

- High Speed

- Buildings set back

- Surface parking in front

- Water retention in front

- No sidewalks

Characteristic of proposed context class, C2T

- Low speed

- Buildings at back of sidewalk

- On-street parking

- Closed drainage system

- Wide sidewalks

- Street trees

- Pedestrian-scale lighting

Design speed is critical, because it determines pedestrian safety and comfort. The FDM does not permit street design in excess of target speed. Also, target speed dramatically changes in the four pedestrian-friendly context zones—C2T, C4, C5, and C6.

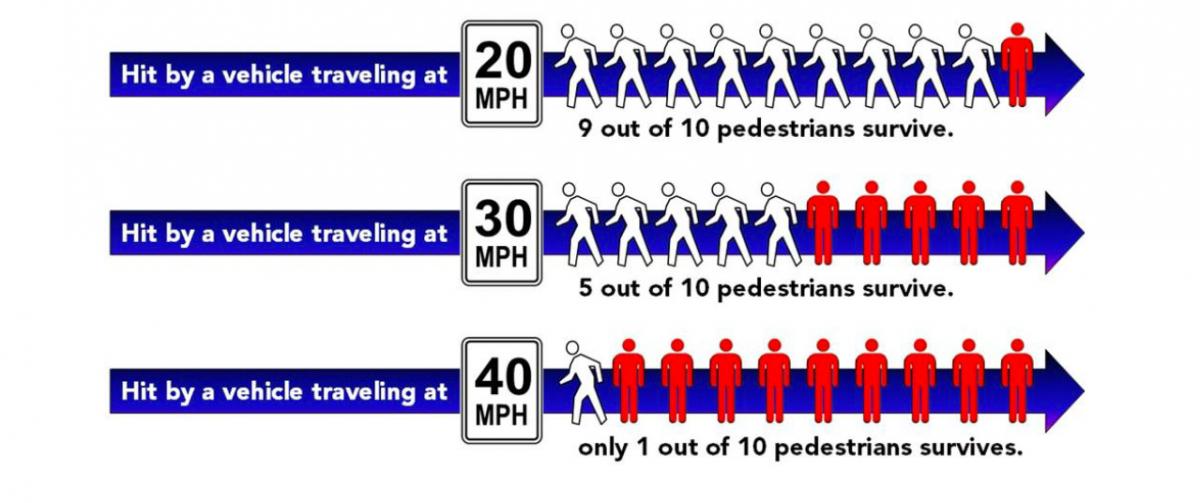

The FDOT standards previously recognized only two design speeds, above 45 mph and below 45 mph. Most of Florida’s 4-, 6-, and 8-lane arterials and collectors are designed for 45 mph traffic, Hattaway says. At that speed, 10 percent of pedestrians will survive getting hit by a car. Chances are that those who survive will have a lifelong debilitating illness, Hattaway notes.

The current FDM includes eight design speeds, from 25 mph to 70 mph. In the four pedestrian-friendly zones, 25 mph is now the default speed. Higher design speeds must be justified by the engineer.

Many aspects of this presentation are informative, such as the difference between three kinds of safety: Normative, substantive, and perceived.

Normative safety is when typical traffic engineering standards are met, and these streets are often not very safe at all. Commercial strip arterials meet all of the current standards, and yet they are among the most dangerous thoroughfares, according to the presenters. Smart Growth America’s Dangerous by Design cites suburban arterials as the most deadly thoroughfare type for pedestrians and bicyclists. Hattaway explains that AASHTO Green Book standards are not predicated on safety research—rather they are based on maintaining the speed and capacity of the roadway.

On the other hand, many historic streets do not meet standards of the last seven decades—and yet they are among the safest streets. They have what Carver calls substantive, or real-world, safety. These streets are typically perceived by pedestrians to be very safe (sometimes streets that appear safe have some kind of specific flaw that reduces substantive safety, however). The FDOT classification system is designed to unite these disparate kinds of safety.

The classification system is consistent with a “vision zero” approach, which views traffic deaths as preventable, not inevitable.

The current situation is the result of:

- A focus on moving cars (roadway design)

- Sprawling land development patterns

- Government zoning that separates uses

The photo above was taken by Hattaway of a mother pushing a stroller with twins on a road without sidewalks—and with multiple other high-speed design aspects. State thoroughfare design is under Florida DOT’s control, but the department has no say over adjacent land use or zoning, which also have contributed to dangerous existing thoroughfares.

The rural-to-urban Transect is the gold standard in describing land use, Carver says. The FDOT classification system is based on the Transect, but does not provide a one-to-one translation to Transect zones. That’s because the system must react to current land patterns in Florida, which are heavily sprawling. “This is reactionary—It describes what is there,” Carver explains.

In unifying land use and transportation, the system creates a common language. In terms of context, engineers previously understood the distinction between urban and rural, yet planners often had a hard time explaining why an “urban arterial” downtown should be different from an “urban arterial” in a rural area. That is especially true when it comes to speed and design criteria. “This was an attempt to get engineers and planners on the same page,” Carver says. “Context classifications convey to engineers how fast we want traffic to move on these roadways.”

In rural conditions, high speed is usually good, because the idea is just to carry traffic long distances, Carver explains. But the speed must be reduced as the road enters a town, and go back up again on the other side. This system and manual gives engineers clear instructions on how to adjust speed to conditions.

The design guidance relates to the width of travel lanes, and much more. Sidewalks, landscaping and trees, parking, infrastructure design, lighting, street furniture like benches—all respond to context. Thoroughfare elements are impacted by adjacent development and land use. Buildings should come up to the sidewalk in a main street format, for example.

Why would anyone outside of Florida care about this system? The vast majority of transportation infrastructure built after World War II, especially in Sunbelt states, is automobile dominant. Yet the problem is not inevitable. Sweden, Netherlands, Australia, and New Zealand show how a change in philosophy can radically reduce the traffic fatalities, especially among pedestrians, Hattaway explains.

Florida has found that a high number—up to nearly 80 percent in some regions—of injuries occur on a few short segments of roadway. If safety on these streets is addressed, the state could achieve large improvements in safety, Hattaway notes. Safety is a virtuous cycle, he adds—when streets are designed for lower speeds, drivers change their behavior and become safer road users.

Although Florida remains the only state that has created such a context-based road classification system, interest elsewhere is growing. “I’m on several national panels that are looking at creating national criteria,” Carver says. “AASHTO is moving in this direction.” Since all states look to AASHTO for guidance and direction, Carver believes change is inevitable. “You can do it now, or wait 10 years for the AASHTO manual, but this is coming.”

The Florida Context Classification System for thoroughfares is an innovative and revolutionary system that should be emulated nationwide.

Watch the whole webinar:

Editor's note: This article addresses CNU’s Strategic Plan goal of working to change codes and regulations blocking walkable urbanism.