Trenton closer to long-sought freeway removal

Urbanism is a long-term activity that plays out over generations. That’s especially true of major infrastructure like freeways—and Route 29 in Trenton, New Jersey, is a great example. In 1989, two young architects, Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, who would go on to help found CNU, drew a plan for Trenton and the Capital City Redevelopment Corporation.

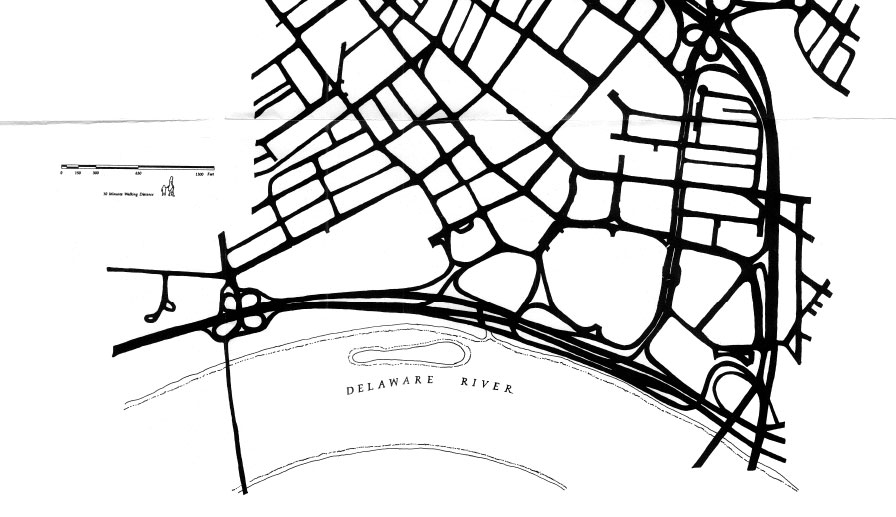

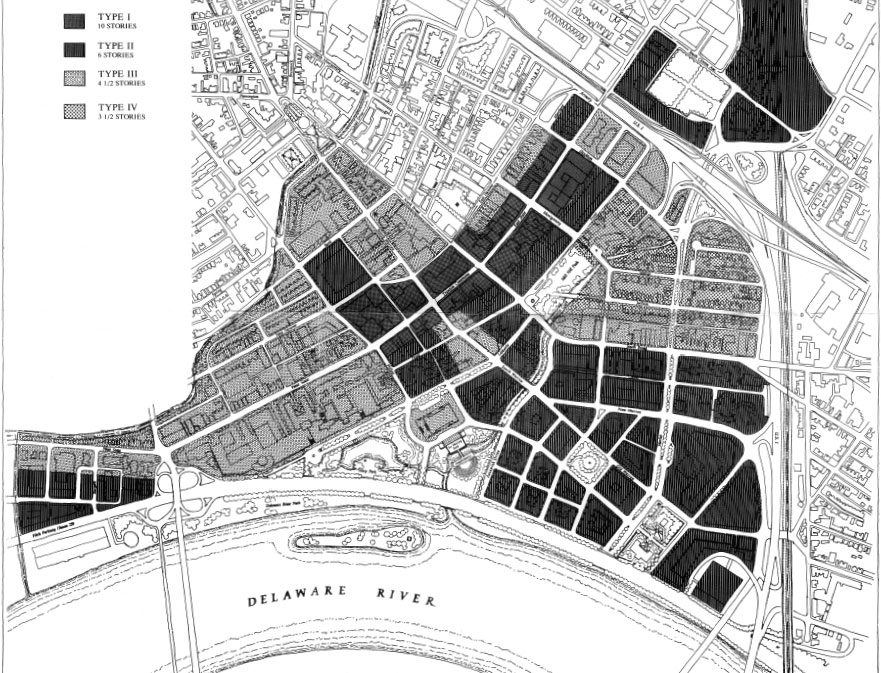

The big move in the plan was to transform Route 29, located between the Delaware River and the city, into a riverfront drive. That idea would open up many blocks for redevelopment with a typological code (a forerunner of today’s form-based codes). The plan was not implemented, but transforming Route 29 from a highway to a surface street never entirely went away. The state DOT authored plans for converting the highway in 2005, 2009, and 2017—and now the concept is moving to the forefront again.

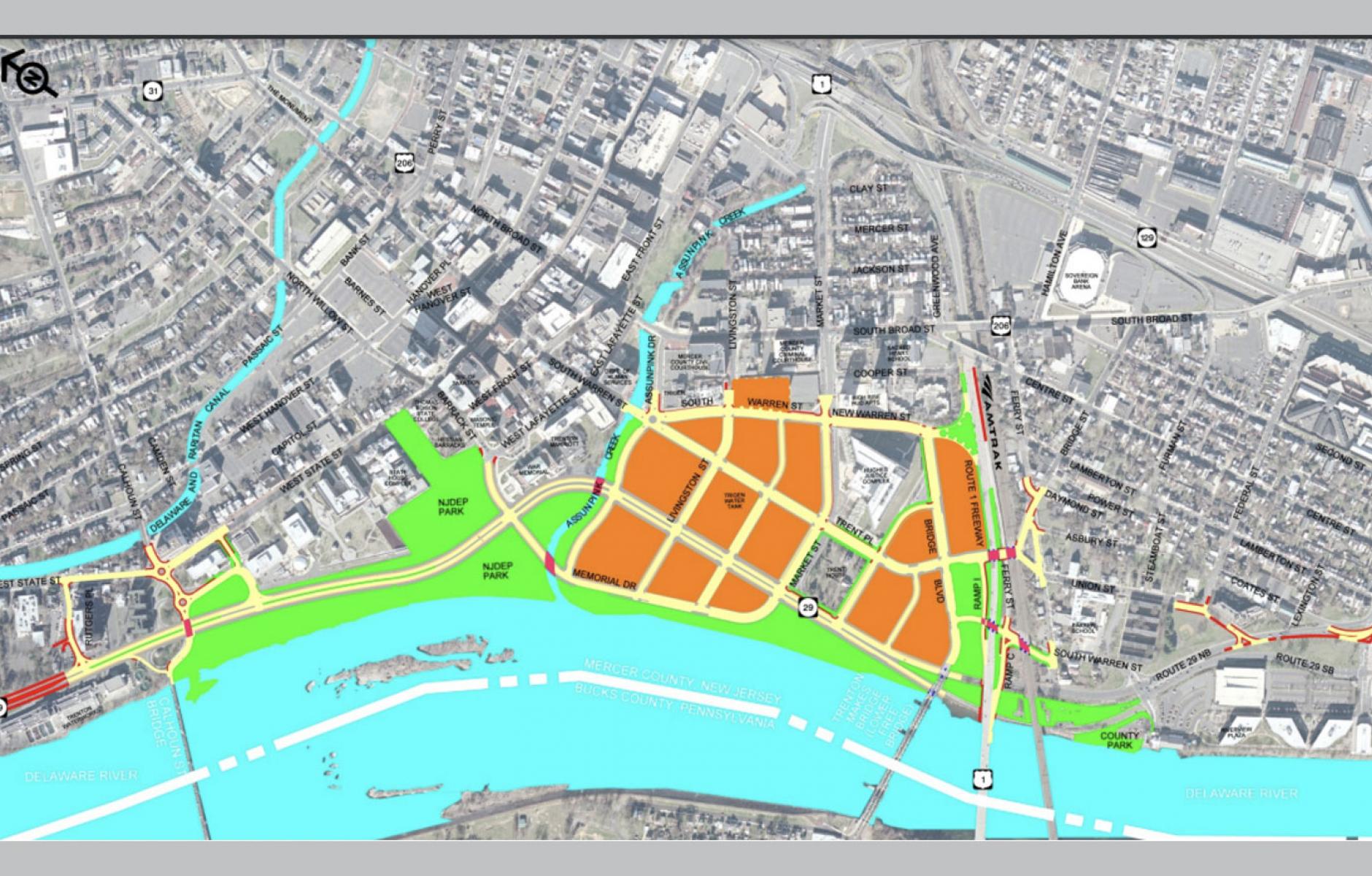

Today’s proposal bears many similarities to the 1989 Capital City plan, in that a similar pattern of urban blocks is created by getting rid of the freeway (see plan at the top of the story). Those blocks accommodate existing state government buildings—and also facilitate new urban development on land that is currently used for surface parking (many historic structures were taken out to make way for the highway and state office parking in the middle of the 20th Century).

A major difference between the plans three decades apart is that Route 29 has been rerouted away from the river for about a quarter mile—and the thoroughfare is now envisioned as a boulevard. The latest route creates developable land along the river and is a relatively low-cost alternative, because it goes through existing parking lots. It also maximizes views of the capital buildings.

When Route 29 was built in the 1950s, and for several generations after, transportation officials believed that the best use of the Trenton’s waterfront was a limited-access highway that cut the city off from the river and fostered disinvestment on nearby blocks. The 1989 plan was the first counter-argument, showing how the city and its economic development could benefit from taking out the highway.

Like many highways in state capital cities, Route 29 was built to expedite the easy commute of state office workers, officials, and people with business in the capital in and out of Trenton. This was done at the expense of the city’s urbanism and quality of life. Ever since the late 1980s, people have been thinking about getting rid of the section of freeway—but that is easier said than done. Increasingly, the political dynamics favor of taking the highway out.

“Currently campaign organizers feel this project can benefit from favorable leadership within the State of New Jersey, as well as with increased federal funding opportunities that prioritize placemaking in urban areas negatively impacted by infrastructure,” advocates told CNU recently. “The campaign has engaged lawmakers, agencies, community organizations, and media throughout its lifespan.”

The project has support from the city’s mayor, staff, the Mercer County executive, key staff at the New Jersey governors’ office, the State Treasurer, in addition to neighborhood groups and business and economic organizations, advocates told CNU in a submission to Freeways Without Futures 2023, a report that CNU will release in April. The submission explains:

“The purpose of this project is to stimulate economic development, improve traffic safety and connections to the downtown street network, reduce flooding, provide increased open space and improve access to the Delaware River by replacing the existing Route 29 freeway with an urban boulevard. In 2005, the ‘Boulevard Study’ showed that a surface street intersected with Trenton’s city grid would improve access to the Delaware River and reclaim 18 acres of prime developable real estate. Pulling the boulevard alignment away from the river’s edge and partially rerouting it through adjacent surface parking lots eventually became the preferred alternative, given its ease and lower costs of construction, as well as better views of the capital buildings and amount of developable land adjacent to the river. This plan included a connected park system, a route to extend the River Line Light Rail, and a trail network, which would make Trenton more navigable by foot and public transit, reducing dependence on cars.”

In other words, there are many good reasons to take out the freeway and move the traffic along surface streets. Over the years, benefits have been explored in subsequent versions of the plan. Route 29 currently carries a little over 40,000 vehicles per day. The straight, wide, lanes facilitate fast-moving traffic and lead to a higher-than-average rate of collisions, according to the submission.

The redevelopment from removing Route 29 would primarily occur on existing parking lots, a reality that reduces potential displacement from subsequent economic development. The city remains distressed, and has experienced little gentrification, the submission states. “The City of Trenton staff are aware of potential gentrification pressures if redevelopment should flourish and have discussed measures that would create mixed-income communities where no residents now live and provide support for lower income residents to remain in the community.”

The boulevard could have a remarkable impact on improving quality of life. Residents who seek to reach the river to fish, for example, are forced to endanger their lives by illegally crossing the highway, the submission states. This project would open whole new recreational parklands. A 2009 study estimated the cost of the project at $140 million.

A report on cnu.org estimates that “The Waterfront Reclamation project could contribute $2.25 billion to the city’s economy while improving access to the river, bicycle and pedestrian connections, vehicular circulation, and traffic safety.”

According to the state’s major online media outlet, NJ.com, “Route 29 could be rebuilt as an urban boulevard and surface parking lots will be replaced by pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use development. Funding will be used to identify studies, review FEMA regulations, and develop a market analysis and promotional materials for the project.”