Historic chance to remove highway barrier, reconnect community

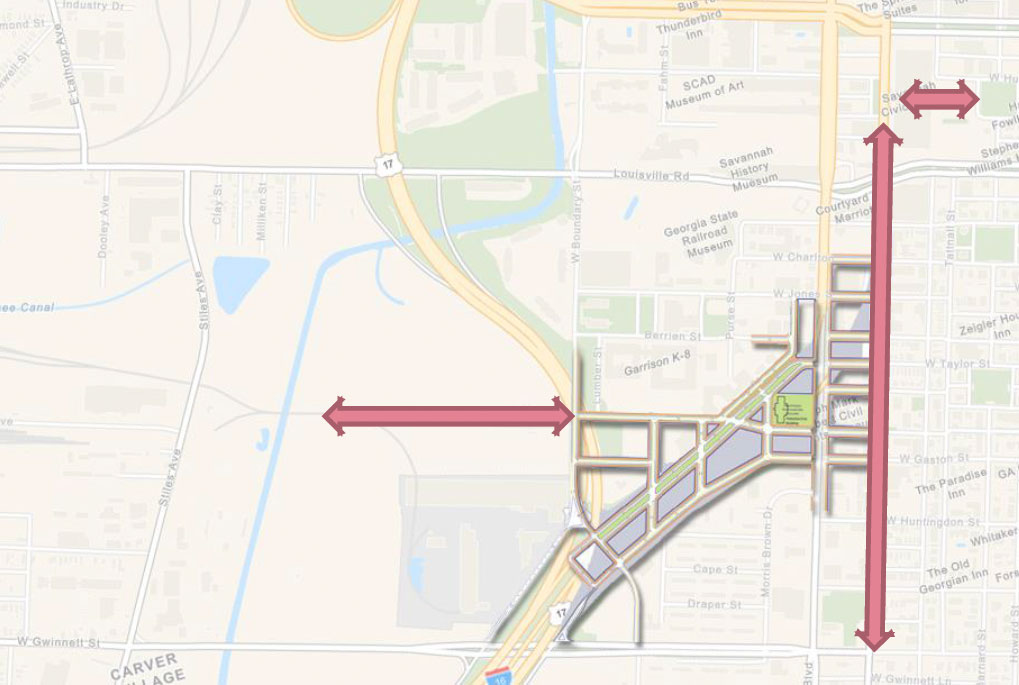

An enormous flyover ramp near the eastern terminus of Interstate 16 in Georgia has divided and damaged a neighborhood in Savannah's historic district for six decades. Removing this interchange would provide many benefits: Reconnecting the neighborhood; healing the wounds of urban renewal in a historically Black and immigrant community; building affordable housing (or at least creating an opportunity to do so); replacing aging infrastructure; and improving traffic patterns and safety.

The project has been studied extensively over the last 10 years, but political momentum has recently gathered steam. In the last two years, flyover removal has gained support from Savannah’s mayor, city council, a state representative, and a US Senator. Now the city has applied for a $1.6 million federal Reconnecting Communities grant to study demolishing the highway spur (it amounts to a short section of highway).

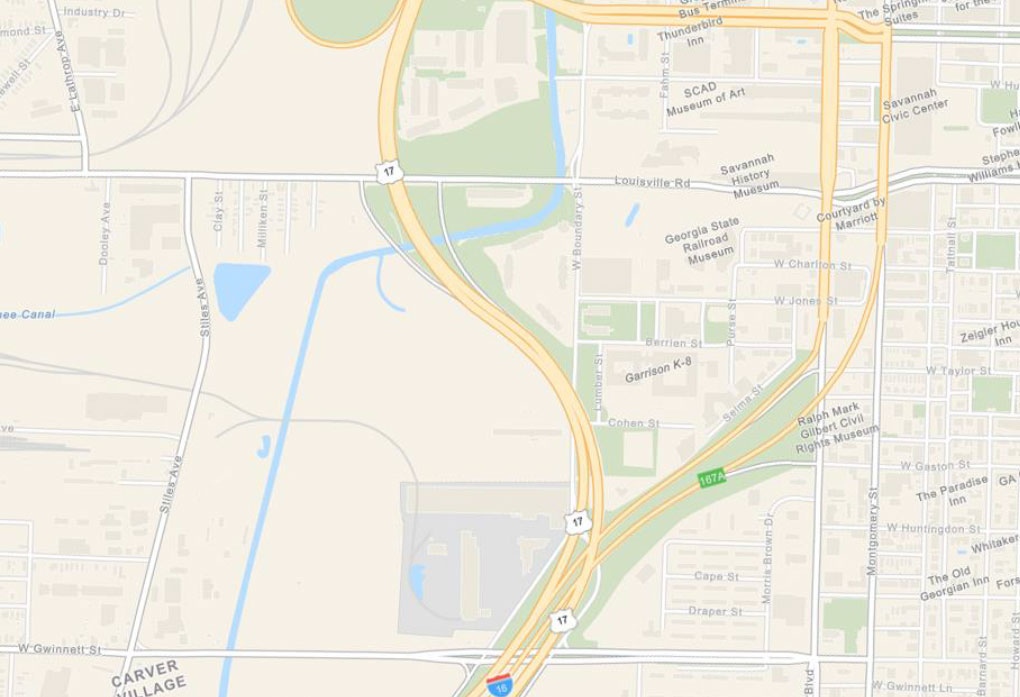

I-16 is the only Interstate with the distinction of cutting into Savannah’s famous historic core, beloved of urbanists, historicists, and lovers of fiction like Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Although local proponents say the Georgia Department of Transportation has been reluctant to demolish any pieces of limited-access highway, the interchange serves little purpose. Other on and off ramps exist nearby. A 2016 engineering report notes that too-frequent I-16 access points in the area may have led to a high number of crashes, due to confusing merging traffic patterns.

US Sen. Raphael Warnock, raised in the shadow of the flyover, wrote a letter to US Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg. “It is a dream of mine to see that community restored,” he said.

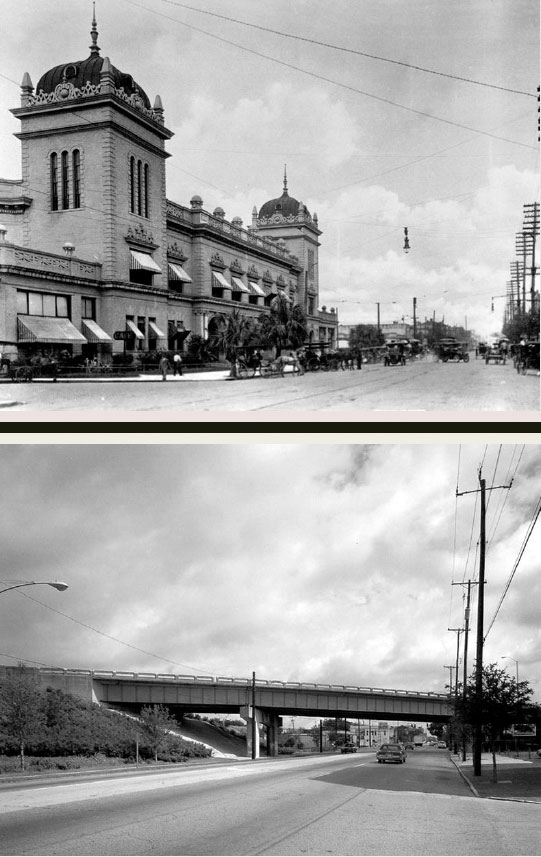

Warnock deplored the impact on his neighborhood. “The Old West Broad Street, which is new Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, was once the center of a thriving community and home to Black families and businesses, as well as many Asian and Jewish immigrants, in Savannah, Georgia. However, in the 1960s, the federal government demolished and paved over landmark buildings, homes, and businesses for a new highway spur.”

With or without that strong statement, the study grant seems likely to be approved. DOT’s Reconnecting Communities program, which CNU had a hand in helping Congress to draft, is one reason why this project has momentum now. As CNU reported a year ago, any city that applies for this type of feasibility study is very likely to get approval. The program allocates $250 million for such studies, and individual grants are capped at $2 million each. Since these studies typically cost less than $2 million, the program will fund at least 125, maybe as many as 200, studies. Moreover, Savannah’s proposal checks many, if not all, of the boxes that DOT is looking for.

The area, known as Frogtown, has two Jewish cemeteries from the 18th Century, and freed slaves settled there in the 1870s. It was the site of the city’s historic Union Station, demolished to make way for the highway. Fine-grained urban fabric disappeared in the neighborhood, which had more than 400 residential and commercial addresses prior to the highway. Only 75 remained in 2010.

When the I-16 flyover was proposed, many residents opposed it, pointing out that even a shorter ramp would have saved many businesses—and Union Station. And yet, it was built and became a durable part of the landscape.

On the one hand, the infrastructure has been in place for a long time (before Warnock was born) and removing it may be hard for many people to imagine, including some representatives of the state DOT. That, in part, explains why such projects take a long time to move forward. On the other hand, this is a historic moment to correct the mistakes of the past and restore a damaged neighborhood in a national landmark district. The current infrastructure dumps fast-moving cars and trucks onto city streets, creating a “firehose of traffic coming into the city,” according to supporters of the flyover removal.

A coalition of public and private organizations and neighborhood leaders, facilitated by the Historic Savannah Foundation (HSF), supports the project. The I-16 Flyover Removal Coalition notes that the infrastructure, which adds no real estate value, would be replaced by streets, blocks, and urban land.

“Traffic demands can be met through the redistribution of traffic onto other streets and interchanges within the area of influence, allowing for the right-of-way to be restored as developable land to support plans for expanding the downtown footprint,” the coalition writes, in an executive summary. The project would restore eight acres of developable land on multiple city blocks and create a site for a new square and civic building. It would revert a significant north-south street, Montgomery, to two-way traffic. Another east-west connection could be established across the highway, facilitating access to Savannah’s Canal District—a redevelopment area with a lot of potential.

At a recent gathering of urbanists, I became aware of the project from Savannah-based architect and urban designer Christian Sottile, who helped to get the project rolling by providing the urban design for a charrette in 2012. Some of the drawings and ideas from that plan have carried forward to the current campaign, which is being co-chaired by Savannah planning practitioners Denise Grabowski and Ellen Harris. HSF has taken a leadership role because of the potential impact on the historic district, and the nonprofit has provided crucial staff resources for the campaign.

The I-16 flyover removal has a long way to go before it becomes reality. Getting the funding for the study would move it forward, but the project still needs environmental documentation, preliminary engineering, final design—and, at long last, construction. The latter would cost around $70 million (2015 dollars), according to the preliminary estimate.

Note: CNU is working on its biennial Freeways Without Futures report, which is due out in April of 2023.