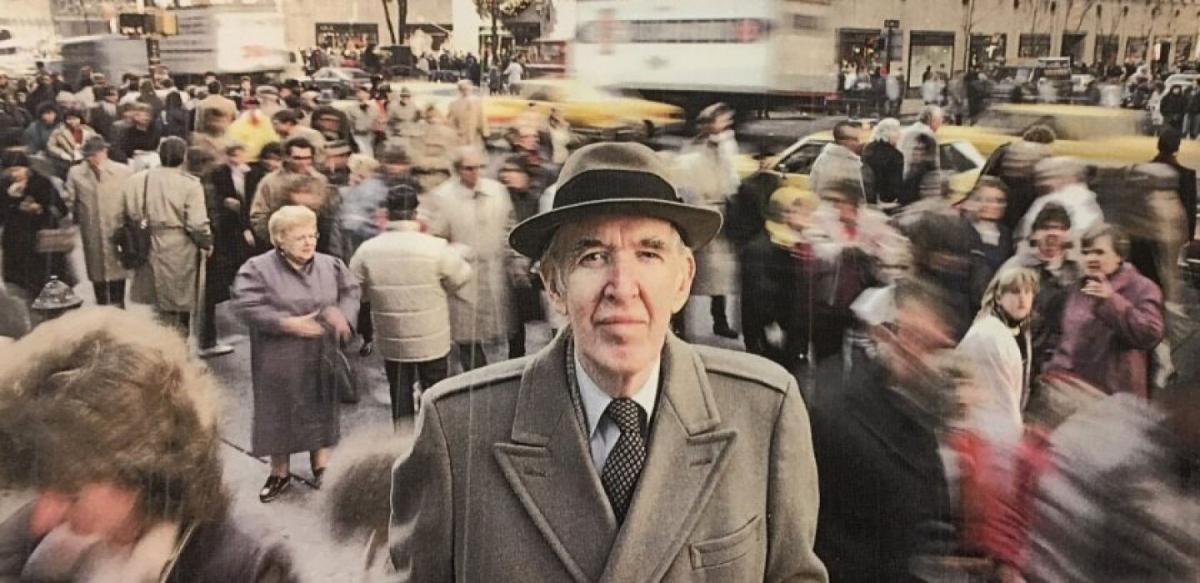

A man who loved and observed cities

William H. “Holly” Whyte is best known, in urban planning circles, for his sociological research into what makes public spaces successful, as reported in his 1980 book, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces.

Whyte, who died in 1999 at 81, used cameras, careful observation, and collection of data to change how designers and public officials viewed urban spaces. Sweeping plazas may look good in plans and renderings, but they are not where people like to gather.

Among his many findings: Public spaces that are elevated from street level by more than a few feet are rarely used. People gather on corners of public spaces, similar to street corners. And, if designers want visitors to linger, they should include chairs and other places to sit. “This may not strike you as an intellectual bombshell,” he joked. Based on his observations, he led the successful redesign of Bryant Park in Manhattan, formerly a haven for drug dealing and violent crime and now a premier public space.

Whyte’s work encouraged designers to look at how people use public spaces, rather than rely on theory. He hired an assistant for his Street Life Project, Fred Kent, who went on to found the Project for Public Spaces, a still-influential organization.

This public space legacy is only the tip of the iceberg of Whyte’s influence on America’s landscape. Richard Rein’s biography, American Urbanist, published by Island Press this year, is a long overdue assessment of Whyte’s contributions to 20th Century urbanism.

I was only vaguely aware of Whyte’s collaboration with Jane Jacobs, one the most important pairings in the history of American planning and city design. Whyte hired Jacobs to write an article for Fortune magazine, part of a series that he edited or wrote challenging mid-century planning and city-making.

Like Jacobs, Whyte was a proponent of the close observation of cities to see what works—a practice that I named “observational urbanism.” His career coincided with a time when traditional cities were being damaged and abandoned; urban renewal was at its peak and sprawl was accelerating.

The Fortune series resulted in Whyte’s 1958 book, The Exploding Metropolis. “Living up to the provocative subtitle of its first edition, A Study of the Assault on Urbanism and How Our Cities Can Resist It, the book would lay out the challenges of the urban agenda that continue in the twenty-first century,” writes Rein. Among the prescient chapters was one by Francis Bello, which first called attention to the problems of induced traffic demand and too much parking downtown. Whyte described suburban sprawl, which he called “urban sprawl,” pointing out that the then-recently enacted Federal Highway Act of 1956 would locate 41,000 miles of new Interstates and interchanges, influencing new development patterns. He called for better coordination between highway engineers and city planners. Whyte sharply criticized urban renewal, the recent bulldozing of neighborhoods and replacement with sterile modernist buildings, which he called “the wrong design at the wrong place in the wrong time.” The book also included an essay by Grady Clay, who soon after invented the term “New Urbanism.”

The book’s highlight was Jacobs’s chapter, Downtown is for People, which led to a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to expand the piece into a book, partly on the strength of Whyte’s endorsement. “I believe the result may prove to be one of the great contributions to the whole field of urban planning and design,” he wrote to Chadbourne Gilpatric, associate director of the foundation. The book turned out to be the 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

He left his mark on other important planning work—he was one of the first critics of “forgiving design,” whereby traffic engineers create a “clear zone” around roadways. To this day, that approach is a topic of criticism and controversy.

Whyte’s biggest legacy may be in open space, an activism that was inspired by his concerns about seeing countryside gobbled up by leapfrog development. Throughout the 1960s, Whyte was both a stirring advocate—writing articles and an influential book, The Last Landscape, and giving speeches—and an expert in the technical aspects of land preservation. According to Rein:

“As author and environmentalist Tony Hiss wrote in his foreword to the 2002 edition (of The Last Landscape), Whyte’s strategy of using easements rather than outright purchase of open space was ‘a huge success, particularly in the last couple of decades.’ Hiss cited the Land Trust Alliance, a national umbrella organization that estimated in the previous twenty years some 1,200 new local land trusts across the country had permanently protected 6.4 million acres of land.” Nearly half of that preservation is in easements.

A writer and editor by trade, Whyte was drawn into practice and academic research in mid-career. He was drafted to write the Plan for New York City 1969, and in his 1970s Street Life Project is still influential on public space design.

Thinker, big and small

Whyte was a big thinker on cities and the American landscape who never overlooked the importance of small details. Is a public space elevated more than three feet from the street? Most people will walk on by. This thinking at the smallest and largest scales calls to mind new urbanists, whose concerns simultaneously range from the details on the smallest buildings to regional plans.

I saw him speak as an undergraduate in the early 1980s, not long after The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces was published. His ideas stuck with me and I eventually joined the new urbanist movement. Still, I haven’t heard urbanists reference Whyte so much over the years—certainly not to the extent that they cite Jacobs or Christopher Alexander.

Whyte was not just an urbanist. He is more widely known for his 1956 best-seller, The Organization Man, which has been described as one of the most influential business management books ever written. He also coined the term “groupthink,” which is still in use. His study of a suburban community for The Organization Man led to a four-decade career in urbanism.

I think he most influenced New Urbanism through a skepticism of dominant 20th Century planning theories combined with a willingness to trust his own observations. Through research, he proved that modernist architects were often wrong in their urban design assumptions.

New urbanists took a similar approach when they designed new towns and neighborhoods. They measured streets that they loved, where cars moved at a speed safe for walking and biking. They noted the distance and height of porches that felt right for sitting. They gauged the scale of public spaces and neighborhoods. They walked, and so did Whyte.

For a meeting on the Route 1 corridor in New Jersey, he walked from downtown Princeton, about two and a half miles, along an automobile-oriented thoroughfare, just to feel what it was like. “When I arrived at the meeting I was greeted with incredulity,” he said. “Walked? From Princeton? People came up to ask me about it. They thought I was some kind of nut.”

This idea of closely observing the city, and developing theories and ideas from those observations, is a thread that runs from Whyte and Jacobs through the New Urbanism. But also, there’s a love and appreciation for the city and the town. Whyte intuited that the physical environment is not something to take for granted. It is an important precondition for the thriving of humanity.

I highly recommend American Urbanist. It’s a fascinating study of a man and an era that have shaped the work and ideas that are having an impact today.