A trenchant critique of traffic engineering

Charles Marohn, founder of Strong Towns, retired as a civil engineer in Minnesota at the end of last week. Marohn is not yet 50, has not practiced engineering in more than a decade, but maintained his credentials as one of the most prominent critics of traffic engineering of our time.

He was caught in a Kafkaesque process for the bureaucratic crime of failing to renew his license on time in 2018. He was targeted by engineers, and a licensing board, who resented his criticism of the profession.

As architect and urbanist Steve Mouzon put it on Facebook last Friday, “This is a great day for Chuck, but a disgraceful day for the State of Minnesota engineering board, who by forcing this great man out of their profession admitted that they couldn't stand up to the truth, and were choosing dogma over life-saving principles.”

Mouzon makes a judgement that is justified after a full review of the petty actions of the board and those who made complaints against Marohn. Follow the links, read all about it, and judge for yourself, but this is insignificant compared to the real story—how we can revive our communities by restoring common sense to the design of transportation systems.

After reading his recent book, Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: Transportation for a Strong Town, I can see why Marohn is a threat—at least to those traffic engineers who don’t like change. Many prominent thinkers, going back to Jane Jacobs—who called traffic engineering a “pseudo-science masquerading as knowledge”—have been critical of those who design roadways. Marohn’s is the most damning and detailed indictment that I have seen.

“The underlying values of the transportation system are not the American public’s values,” he writes. “They are not even human values. They are the values unique to a profession that has been empowered with reshaping an entire continent around a new experimental idea of how to build human habitat.”

Confessions of a Recovering Engineer offers trenchant views on the function and design of thoroughfares, the problem and value of congestion, traffic studies, transit, transportation’s role in the economy, the insider language and tools that traffic engineers use to get their way, and more.

Traffic engineers have reshaped America. The thoroughfare system today is radically different from the network that existed up to 1950—although those older streets and roads continue to function well today. In historic cities and towns, old streets are the bones of the most sustainable, high-value places in the country. The new and updated thoroughfares are the foundation and framework for sprawl.

The engineering profession has slowly, incrementally, begun to shift its positions—especially around the “complete streets” concept that thoroughfares are not just for cars, but need to serve all users. Marohn argues that traffic engineers have absorbed complete streets mostly by adding facilities to thoroughfares, such as bike lanes and crosswalks without changing their underlying values that prioritize—in this order—speed, volume of traffic, safety, and cost.

Engineers tend to design “complete streets” that aren’t streets, rather a combination of street and high-speed road that he calls a “stroad.” Stroads are the worst of both worlds—they are dangerous, tend toward congestion, and don’t support the high-value walkable environments of a human-scale city or town.

Marohn is right—while there are great engineering practitioners who design excellent streets, they are still exceptions. The default design is for thoroughfares that work against any sense of place that makes people want to get out of their cars.

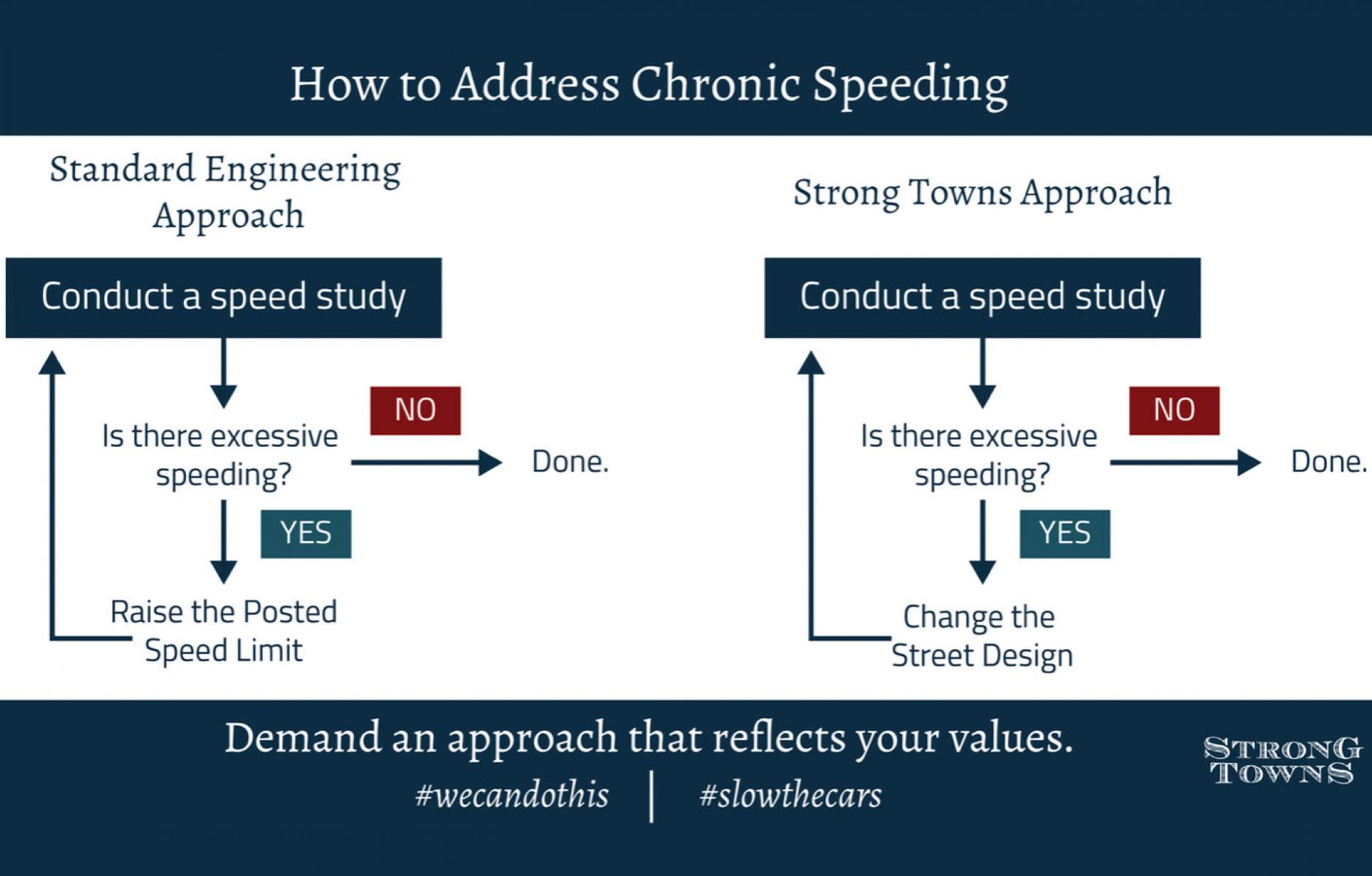

The bottom line is that traffic engineering still values thoroughfares where cars move fast—the more cars the better. These values are not communicated to the public and are obscured in technical reports and jargon. That approach works for highways, but is totally unsuited for neighborhoods, main streets, and downtowns where the street serves as the public realm. Marohn explains how engineers pretend that designing for slow speeds is not their job.

“Professional engineers understand how to design for high speeds. When building a high-speed roadway, the engineer will design wider lanes, more sweeping curves, wider recovery areas, and broader clear zones than they will on lower-speed roadways. There is a clear design objective—high speed—and a professional understanding of how to achieve it safely.

“There is rarely any acknowledgement of the opposite capability, however: That slow traffic lanes can be obtained by narrowing lanes, creating tighter curves, and reducing or eliminating clear zones.

“High speeds are a design issue, but low speeds are an enforcement issue.”

That traffic engineering experiment has failed in many respects, and Marohn describes several case studies in detail—one in Springfield, Massachusetts, where a little girl died in front of a library due to a road that prioritizes speed and volume. The city engineer’s intransigent response, quoted at length in the book, falls back on standards rather than judgement, a common tendency throughout the profession. “In a unique situation like state street, where, it should be reiterated, multiple people have died, citing standards as a reason to do nothing is not merely wrong; it is malpractice,” Marohn explains.

A proposed highway in Shreveport, Louisiana, is a case study of another kind of malpractice, which is the misuse of traffic studies to justify huge, expensive highways that add very little value and destroy neighborhoods. Marohn shreds the intellectual basis for arguments in favor of I-49 in Shreveport, based on specious statistics, along with similar reasoning for many in-city highways across America. The case against I-49 is damning, and the highway should be scrapped. “For an engineer, a conservative approach is not one that reduces the size and budget of a project, opting for a more incremental approach. No, a conservative approach means massively overbuilding everything under the guise of penny wise, pound foolish,” he says. Ouch.

The neighborhood threatened by I-49 is Allendale. Despite its low average income, Allendale is the kind of neighborhood that Marohn refers when he writes: “Wherever development patterns are most productive, wherever the highways value per acre is measured, those are the places where people will be found outside of a motor vehicle. … People are the indicator species of success.”

I think the most important aspect of the book deals with design, despite Marohn never presenting specific designs. Marohn offers a theoretical framework for how to design better thoroughfares, ones that unlock the human potential of cities and towns. We need to start thinking clearly about whether a thoroughfare is a road or a street, Marohn says. A road links places, but a street goes through places and is the locus of community life and value. The critical difference is design speed.

“The only way to have meaningful reductions in speed, and a significant impact on the number (and severity) of crashes, is through ‘geometry change,’ ” he writes. The geometry of stroads must change to reform a lot of badly functioning places in the US.

Confessions of a Recovering Engineer presents a clear vision of where we need to slow traffic, and how, to create high-value places. Marohn’s book should be required reading for every current and aspiring transportation engineer in the US.

I look forward to the time when Marohn can get his license back. In the meantime, may his important work continue to have an impact.

Note: I am a fellow of CNU, and so is Marohn, and I have known him on a professional level for more than 10 years.