A brief history of retail and mixed-use

This is one of a series of ongoing Public Square articles on the market, technological, and cultural transformation of the $5 trillion retail industry—and how it relates to a continued shift toward walkable, urban living.

In the beginning, we built beautiful main streets and downtowns, and we all agreed that they were good. We can see them today in ancient settlements like Pompeii. Shopping streets go back to the early days of civilization.

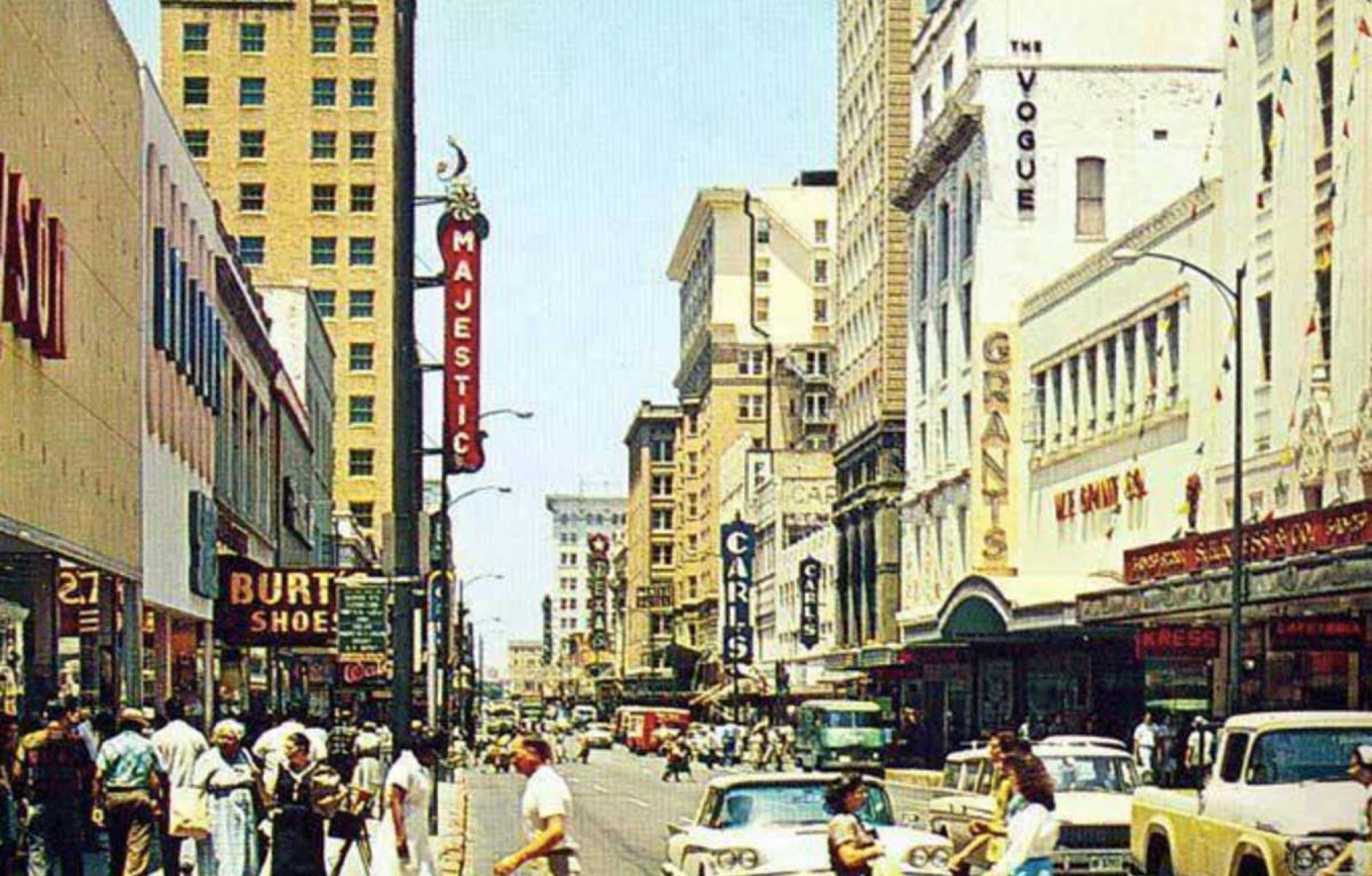

Even through the 1950s, nearly everybody went downtown to shop, pick up the mail, visit the courthouse, go to the bank, and take in a movie or other performance. Downtown storefronts and mixed uses performed essential functions of life. “The diversity of land uses created a synergistic environment that was walkable and a great place for social interaction—a place to see and be seen,” notes Sharon Woods of LandUseUSA | Urban Strategies, a market research and analysis firm.

In a memoir, The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, Bill Bryson describes 1950s Des Moines, Iowa, where downtown was filled with magnificent department stores, shops, and restaurants. The city’s greatest retail institution was Younker Brothers department store, which had a fancy tea room, the state’s first escalator, and the store occupied two buildings—you could start shopping on one side of the street and come out on the other side, Bryson notes.

Then, downtown seemed to change overnight. By the late 1950s buildings were being knocked down to make way for parking lots, and shopping centers and hotels were being developed along the highway outside of town. “By the early 1960s, people exchanged boasts about how long it had been since they had been downtown,” Bryson writes. “They had found a new kind of happiness at the malls.”

A similar story was playing out nationwide. The first regional mall in the US opened in 1956 (In Edina, Minnesota, with scores more built soon thereafter). Some downtowns and main streets did better than others, at least for a while. But many soon emptied out in favor of shopping centers and department store anchors surrounded by acres of parking.

Ironically, cities were converting to one-way traffic systems to handle downtown traffic just as the same traffic was abandoning the downtowns for the suburbs. One-way streets were often instituted in the name of public safety and to move vehicles through downtowns more efficiently. However, the one-way streets encouraged higher speeds for vehicles and impacted the exposure that merchants had to traffic and potential shoppers.

If that wasn’t bad enough, on-street parking soon vanished along state routes to make roads wider. Departments of transportation seemed to share one belief—that roads serve only to move lots of traffic through fast. Many cities followed the state trends by removing parking along their main streets, perhaps thinking that more and faster traffic would bring more shoppers. Unfortunately, it created automobile raceways that reduced walkability and livability.

Highways and bypasses

Meanwhile, the federal government was funding Interstate highways and bypasses around downtowns. The first mile of Interstate opened in 1955, just before the first regional mall. Sadly, federally funded urban renewal gutted entire neighborhoods, fragmented communities, and diverted traffic away from downtowns. Retail sales for many downtown merchants plummeted and they gradually closed or relocated out to the newest mall.

As the downtowns unraveled, anchor institutions also fled, including courthouses, post offices, banks, colleges, hotels—and jobs. When these anchors and the jobs left, so did the workers and residents. Many of these actions were intended to save cities, but they inflicted great damage instead.

Dying downtowns and declining jobs were among the many reasons that, by the mid-1960s, people were moving out of US cities in droves—a trend that continued for 30 years.“Sprawl hastened the abandonment of Main Streets and City Centers with their small-scale, personal, and diverse retail and commercial offerings,” notes Stefanos Polyzoides in a forward to urban planner and retail expert Robert Gibbs’ book, Principles of Urban Retail Planning and Development. The new malls had centralized management and a coordinated tenant mix that downtowns could not match. Between 1954 and 1977, the total retail market share of American city centers dropped by 77 percent, Gibbs wrote, and many downtowns and main streets eventually lost 90 percent of their business.

While city and town centers struggled, retail and commerce continued to evolve and thrive—indeed the era of conventional suburban retail was just beginning. Department stores like Sears, JCPenney, and Macy’s were almost exclusively located in the downtowns even during the early 1950s. But by 1960, they were relocating to the regional shopping centers.

New street networks, new retail

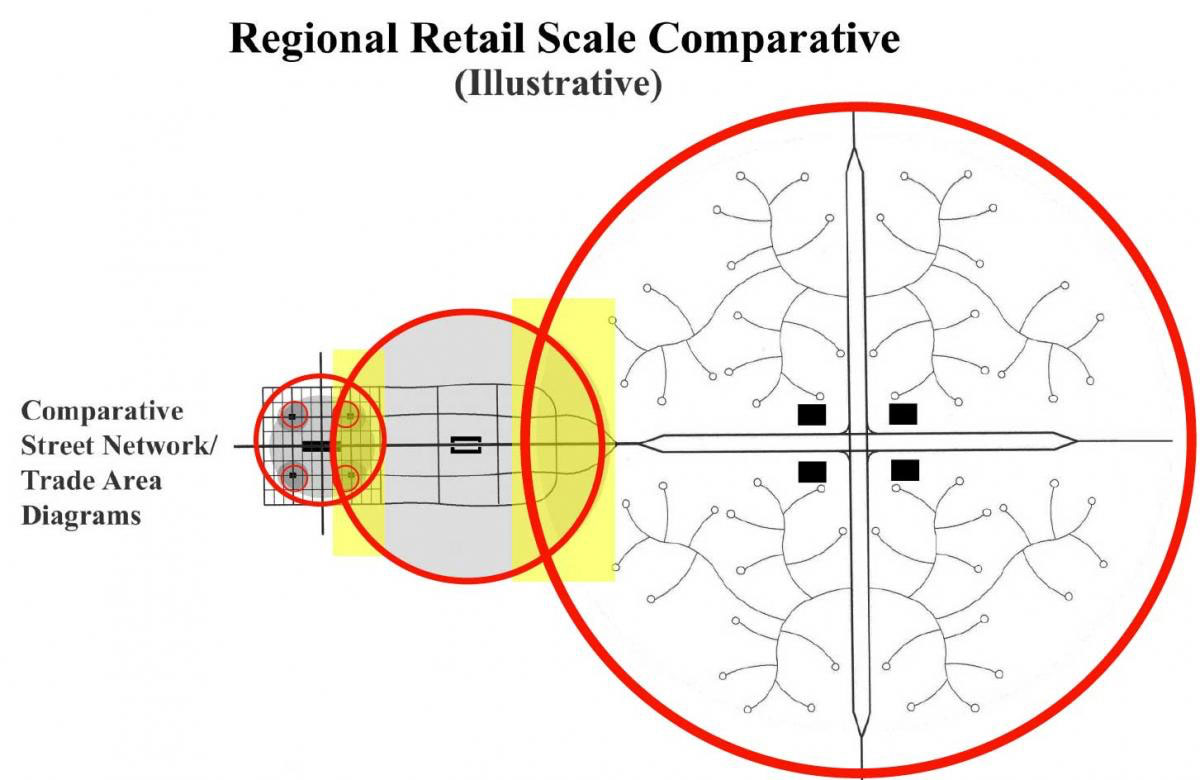

New street networks in the suburbs concentrated traffic onto highways and arterial roads, which funneled shoppers to whole new categories of retail. The first Walmart opened in 1972, and the chain expanded quickly along with other big box discount stores like Kmart and Price Club. Then came the “category killers” like Home Depot, Builder’s Square, Lowe’s, Circuit City, Oshman’s Sporting Goods, Miller’s Outpost, Wickes Furniture, Bombay Company, and Linens ‘n Things.

These stores were built at a feverish pace wherever arterial roads and limited-access highways came together. The 1990s was the peak era for building automobile-oriented retail in the US. In 1990, the US already had more per capita retail space than any other nation. US population grew by 12.6 percent during that decade, and retail space more than doubled, according to a 2018 presentation at CNU by Kennedy Smith, an expert on main street economics.

Over-retailing of America

The United States became the most “over-retailed” nation on the planet. By the early 2000s, the US had multiple times the retail of other nations with similar wealth. Growth in US retail has slowed since then, but even so, “Retail square feet per capita in the United States is more than six times that of Europe or Japan,” said Richard Haynes, CEO of Urban Outfitters, in 2017.

The publicly traded, Fortune 500 companies that owned national retail chains helped to set in motion a building frenzy, says Woods, a sales forecaster for new stores for Dayton-Hudson, Federated Department Stores, and Kmart Corporation during the 1990s. “Some national chains were adding stores to calm the nerves of fickle shareholders. Other chains were over-building stores to lock up entire geographies and prevent competitors from entering with ad campaigns that forced down prices. Some chains also justified over-building as a strategy for relieving pressure on ‘sister’ stores within the same division, or to leverage geographic efficiencies in the supply and distribution chains. All of the practices contributed to the over-building of stores across the nation.”

National retailers were enabled by the new suburban street networks that aggregated tens of thousands of shoppers daily at specific intersections and arterials—and these shoppers almost exclusively accessed physical stores in the pre-Internet era, explains Seth Harry, an architect who has worked closely with national retailers since the 1980s. This aggregation encouraged ever larger formats—epitomized by big box stores and category killers.

The Internet and urbanism

But when Amazon was founded in 1994, the Internet era began. Americans were already used to buying by catalog—they had done so throughout the 20th Century—and e-commerce firms employed similar distribution networks (in some ways Amazon is the new Sears, just more powerful). Consumer connections were greatly enhanced and more dynamic through the Internet, and this technology “blew a major hole” in the theory of aggregating consumers in physical stores, because goods could be purchased anywhere from a computer, Harry explains. Internet sales grew slowly, and even in the early 2000s amounted to 1 percent of retail.

Also, many of the nation’s downtowns began to recover in the 1990s. Declining urban crime and the New Urbanism prompted a change in market preference for living in walkable, urban places. Retailers began to experiment with mixed-use town centers and “lifestyle centers” to recreate and/or mimic main streets and downtowns.

This idea began as a niche strategy, but the long-term staying power of the market shift toward urbanism became apparent in the first decade of the new millennium, positioning retailers to take the urban approach mainstream, Harry says. Then, in 2008, the nation’s economy went into a tailspin, and banks simply stopped lending for new construction—especially anything that appeared remotely “innovative,” such as urban retail designs.

"Like most other industries, the evolution of retail was greatly impacted by the Great Recession,” Woods explains. “The recession significantly altered the mood of shoppers across all incomes, and value shopping became the new norm rather than the exception. Shoppers from all backgrounds—including the well-to-do—developed a new pride in finding bargains and being thrifty; and paying full retail price was no longer a status symbol. This shift in attitudes had a negative impact on upscale brands and department stores like Macy's, Nordstrom, Sak's Fifth Avenue, and Neiman Marcus. New value-priced brands popped onto the scene, particularly among dollar stores, membership warehouse clubs, discount stores, and outlets stores."

The search for authenticity

Millennials, and to a degree Boomers and GenX, have recently been asking for more “authentic” experiences in their purchasing, Harry notes. They want local goods and venues connected to the creation of the product—craft brewpubs, local cafes that roast their own coffee, local food and farm-to-table restaurants, and the “maker” trend are emblematic of that demand. This is another “back to the future” trend—up to the mid-20thCentury, nearly all US shopping was local and unique to place.

At the same time, young professionals—along with retiring Baby Boomers—continue to re-inhabit cities in large numbers. Housing in walkable places tends to have less space to store “stuff.” Each US household owns about 300,000 consumer items, Smith reports. Millennials and the emerging Gen Z are environmentally conscious, and they may simply want to buy less new stuff going forward, she believes. “We are just going to see less mass manufacturing, and this will affect shopping malls, which will quickly become outdated venues—except for major regional malls,” Smith says. But, she adds, “These are good times for downtown retail in general.”

Walkable urban retail is growing and commands significant rent premiums, according to Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metro Areas, 2019, by George Washington University School of Business and Smart Growth America. Retail in Walkable Urban Places (WalkUPs) commands substantial rent premiums in every metro area. Since 2016, WalkUP retail grew as a percentage of the total market in 21 of 30 metro areas, remained the same in 5, and declined in 4, according to Foot Traffic Ahead.

That shift has led to the success of smaller, urban format stores like CityTarget opening in walkable urban places in recent years. People with buying power have been moving back into the core of cities and urban centers in the suburbs. Not only is retail following, but also it is changing form to match the urban context.

Downtowns and main streets are mixed-use places, and urban retail will be accompanied by many other kinds of storefront businesses—such as professional offices, salons and other services, restaurants and cafes, entertainment venues, and even civic, not-for-profit uses. “Retail was never the major component of healthy downtowns—no more than 15-20 percent of square footage,” says Smith. Independent businesses are a big part of this trend. National retailers tend to be to no more than 10 percent of downtown retail in “hot” downtowns, she says—even though they appear to have a larger footprint because they occupy the most visible corners.

Meanwhile, e-commerce has steadily grown. It amounts to about 14 percent of total retail sales in the US in 2019. All of this has negatively affected conventional brands that overbuilt retail in the 20th Century.

Trouble and opportunity

The Washington Post recently reported on a “retail apocalypse,” as major retailers have announced significant store closings in recent years. “Payless ShoeSource, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in February, is closing all 2,100 of its U.S. stores, while Gymboree is shuttering its 800 locations. Sears, which has closed 1,300 Kmart and Sears stores since 2013, is scrapping an additional 80 locations. A number of other retailers, including Gap, have hinted that store closures are on the horizon,” the Post reports. One analyst, UBS, predicts 75,000 US stores will close by 2026—and 25 percent of sales will be made online that year, assuming e-commerce continues to grow at a rapid pace.

The purge of name-brand stores is real, but brick-and-mortar stores also continue to open around the US at a steady clip. Many of these are dollar stores, but they also include new brands that are merging e-commerce with physical stores. The reasons behind retail closures and dying malls are complex, and go well beyond the rise in e-commerce. A retail reckoning is long due, and many chains suffer from too much Wall Street debt.

Every massive shift brings opportunity, and as name-brand businesses in malls and automobile-oriented suburbs close, look for mixed-use in walkable urban places to gain market share, especially for new and independent retailers who embrace an Internet presence. “I keep telling my clients that retail is not dead, but rather they must adapt and grab a piece of the action with e-commerce,” Woods says. “Shoppers are building brand loyalties online, and that will translate into more brick-and-mortar store visits—Now that big-box retail is contracting and ‘right sizing,’ this is the perfect time for downtown merchants to take back market share.”

Note: An earlier version of this article said e-commerce is about 10 percent of total retail sales, but that figure was from 2017 and used different sources. Based on further research, we revised the figure.