Time to restore the grid

I-81 in Syracuse is more personal, to me, than the other nine projects in CNU’s Freeways Without Futures 2019 report. I live about an hour from Syracuse in the small Upstate New York City of Ithaca.

New York cities have been devastated by freeways. The state had a wealth of industrial cities in the 1950s when the Interstate system was planned. New York was also the State of Robert Moses, one of the most powerful non-elected officials in US history, who used his power to plough highways through scores of neighborhoods in New York City and elsewhere, displacing countless families and businesses. New York State was, perhaps, the richest place on the planet in those days, with too much excess money to spend on untested planning theories that ignored how cities worked at the neighborhood level.

Not coincidentally, my state was also home to Jane Jacobs, whose ideas offered a powerful counterpoint to Moses and others like him, and eventually laid the foundation for New Urbanism.

Ithaca was somehow spared, by its size and geography, this freeway frenzy. Its metro area (just barely qualifying as a metro by population), is the only one in the nation without a limited access highway leading in or out of the region. We have a short limited-access highway, part of State Route 13, blocking the city from much of its lakefront. I have been involved in planning efforts to turn a portion of that highway into a boulevard, an idea that I believe will be implemented someday. If an Interstate highway had been built through Ithaca, it would have replaced Route 13, and it would have done far more damage than the current freeway segment.

Also, not coincidentally, Ithaca has the strongest economy in Upstate New York, the only city north of the New York City region that has steadily grown in population and jobs since 1970.

Syracuse has not been as lucky, and the elevated highway thrust like a dagger through its core and nearby neighborhoods contributed to the city’s misfortunes. This aging highway badly needs replacement today. In hindsight, it should not have been built. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has called the elevated viaduct “a classic planning blunder.” Now, transforming Route 81 represents the city’s best opportunity to rise like a phoenix in the 21st Century.

Like most New York cities (outside of New York City and Ithaca), Syracuse has lost population in every decade since 1950, although that population loss has slowed in the last two decades and downtown has begun to revive. But still, there is the highway. The entire corridor through the city is marred by vacant lots and devalued properties.

As we report in Freeways Without Futures 2019:

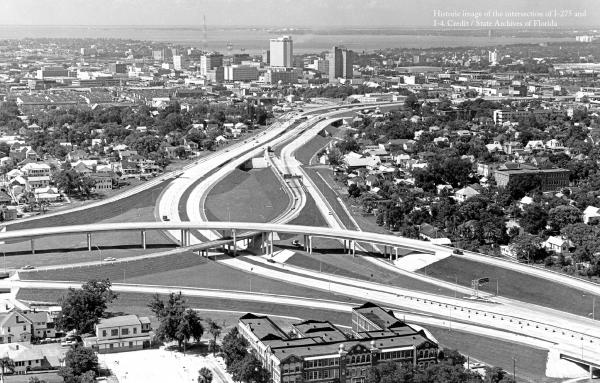

“For over five decades, the elevated 1.4-mile stretch of I-81 known as ‘The Viaduct’ has split downtown Syracuse in half. The urban neighborhoods around the highway have suffered from its construction: It destroyed a historic African-American community, disrupted the flow of city streets, and paved over countless historic homes and sites. The disparity it has created between those who could afford to move to the suburbs and those who remained contributes to Syracuse’s high poverty rate.

While Syracuse’s downtown revival has helped, the city’s biggest economic development effort in this century has been a mall. Called “Destiny USA,” this “silver bullet” project is Syracuse’s answer to Minnesota’s “Mall of America.” I’ve been to Destiny USA a few times, and it has a couple of cool features. For a mall, it has some nice restaurants, although not nearly as nice or interesting as the restaurants in downtown Syracuse—or any respectable downtown, for that matter. It also has a “rope walk.” I like rope walks because I enjoy the sense of danger, while being perfectly safe, and the physical challenge. But compared to rope walks that are built in nature, Destiny USA’s rope walk is the equivalent of a hotel exercise room compared to a serious weight room, or Chipotle Grill compared to a real Mexican restaurant. Other than those and a few other features, Destiny USA is just. a. mall. Big parking lot. Glitzy building that looks like it was poured from a giant container onto a sea of asphalt, or perhaps landed from outer space on an enormous pad built for alien transport. It is the most prominent single feature seen from Route 81 going through the city.

Route 81 is an important Interstate for trucking, but there is an alternative route around the city, and I-81 could be redirected with minimal additional travel time. A primary purpose for the highway in its current configuration is for suburban residents to shave off a few minutes in their trip through the city, without stopping, often going to the mall.

To sum it up, Route 81 in Syracuse is terrible for the city and its neighborhoods, and good for the mall. It is also good for suburban residents, providing they buy the argument that the health of the city at the heart of their metro area has no impact on their lives. Downtown Syracuse has been around for 200 years, and it is clearly the most important economic and cultural real estate in the region.

The mall has been around since 1990, expanded in 2012, and it is fragile. It is highly vulnerable to changes in retail, because it is all retail, and retail is a sector of the economy that is changing fast, with huge disruptions—the long-term implications of which cannot be predicted with accuracy, even by experts. The facility relies largely on one mode of transportation, cars, and is vulnerable to fluctuations in transport technology, oil prices, and mobility preferences—all of which are X factors in the coming decades. The mall also depends on a 19-screen cinema, an important anchor—so that part is stable because we haven’t seen any changes in the “motion picture” industry in recent decades (oh, wait … ). If a mall is destined to fail at some point, there is zero reason to believe that any federally funded Interstate project would save it. (Although the mall is located to the north of the viaduct, mall owners have opposed rerouting the highway because it would no longer be on the official I-81.)

The city is wisely inclined to bet on downtown, and the restoration of a resilient street grid—neither of which have ever required federal largesse. Quite the contrary. Also quoting from our report:

“Recently elected Syracuse Mayor Ben Walsh campaigned with the community grid as part of his platform. But he was far from alone; three of the four mayoral candidates last election came out in favor of the grid—as a group they garnered well over 90 percent of the vote—and Common Council is also on board. …

“The community grid option also has social and economic upsides for the city. The removal of the highway has the potential to return up to 18 acres of developable land to the city. The American Institute of Architects I-81 Task Force estimates that redevelopment of this land could result in the creation of $1.5 billion in property value and $3.6 million annually in tax revenue.

“This redevelopment is an opportunity to create more inclusive opportunities for the members of Syracuse’s community historically left out of the system. The Syracuse Housing Authority, which already owns land along the I-81 corridor, foresees being able to add another 600 below-market-rate units.”

From a cost standpoint, this is not merely a question of “six of one, half dozen of the other.” Replacing I-81 with a “community grid” would cost $1.3 billion, rebuilding the viaduct would cost $1.7 billion, and a tunnel option would cost $3.6 billion, according to a 2017 study. At the very least, the grid is expected to save $400 million over the next least expensive option.

The tunnel would likely cost even more than its sky-high estimate, due to the complexity of such projects that typically experience huge cost overruns. Boston’s “Big Dig” cost 2.5 times its original estimate—even accounting for inflation. The tunnel would disrupt the city far longer with its complicated, costly construction, and would be more expensive to maintain—and it would still involve demolition of buildings. Support for the tunnel from outside the city has delayed a decision on I-81. My taxes, and yours, would be used to pay for this boondoggle.

We often accuse generals of “fighting the last war.” Even worse is repeating, at much higher cost, a mistake that we know was a mistake. And doubling down on that error.

The right decision for Syracuse is clear. Place your future on the solid foundation of a prosperous downtown and city neighborhoods. The city does not owe its history, culture, or economy to a shopping mall. With or without a rope walk.

New York State should get busy, correct the “classic blunder,” restore the city’s grid, and let Syracuse thrive again in the 21st Century.

Note: CNU's sixth biennial Freeways Without Futures report was released April 3. Freeways will be a topic at CNU 27 in Louisville June 12 through 15. Discounted registration is available until May 10th.