Overselling utopia? The urbanist’s dilemma

Generally speaking, the description of any Utopia that involves many details is apt to be an unconvincing way to present a principle which can be applied effectively in practice with immense flexibility as to details …

—Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. to Henry James, July 10, 1924, Papers, Regional Plan Association, Cornell University

A cadre of government, activists, academics, developers, and the technology sector are moving forward with fine-tuning cities in new contexts, with specific lists of attributes and goals. Among the inevitable focal points of any prescription: smart, affordable, walkable, mixed-use communities with live-work proximity, green and sustainable features.

But the age-old dance of human and machine provides considerable fodder and fascination from history, including the risks of indiscriminate cliché versus the realities of sociocultural and market implementation.

The vision, chasing utopia

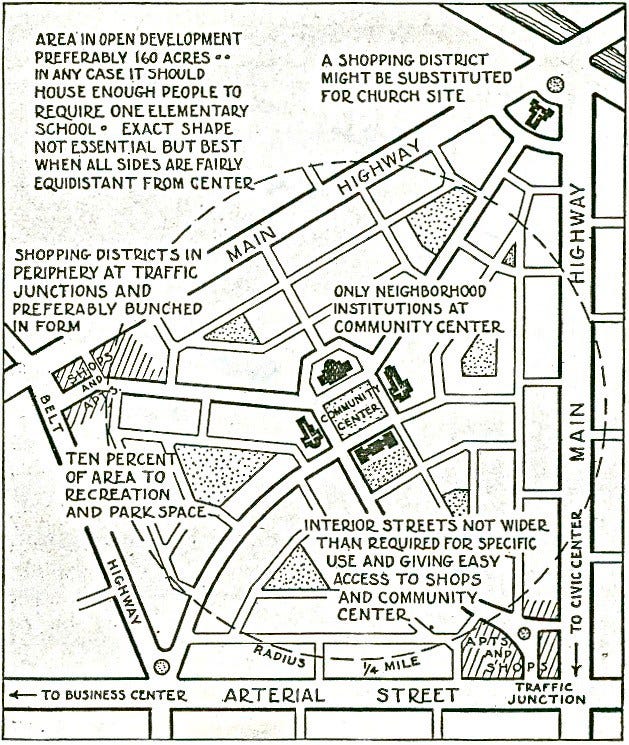

In the 1920’s, planners in the New York region wrestled with how to re-plan cities and suburbs — “community planning”– amid the ascent of the automobile. Like today’s urbanists, consultants, developers, and technology vendors, they sought to educate decision-makers and ordinary citizens about contemporary best practices and related development patterns.

They had some good ideas, inherited from Garden City thought, planned, compact industrial towns and utopian communities, which by and large have been rediscovered, or otherwise withstood the test of time.

Like today, planning activities of a century ago sought improved residential quality, including a scheme which correlated scaled streets according to use, local stores, the community school, parks, playgrounds, open space, and social interaction among neighbors.

Some even thought about how to sell the message, and the intended audience for the neighborhood focal point. For instance, Shelby Harrison characterized the then-nascent neighborhood unit studies of his colleague Clarence Perry at the Russell Sage Foundation:

We need to reach large numbers of citizens who are not thinking very much in social or planning terms — among them builders, real estate developers, and local civic leaders. It won’t be so familiar to them, and the line of thought will have to be presented in some detail if the idea is to be made clear.

—Shelby Harrison to Thomas Adams, December 1926, Papers, Regional Planning Association, Cornell University

Voices from History

These principles were later criticized for oversimplicity, “architectural determinism”, and what we would today call an underemphasis on social equity. The community planning tradition attempted to incorporate the social cohesion observed in successful organic communities into new areas, naively assuming that such cohesion came with the provision of successful communities’ physical facilities. With the provision of churches, local stores, and other structures at the community level, the thought leaders of the time assumed all else would follow.

British sociologist Maurice Broady said it best in 1966. Architectural determinism was given credence in the neighborhood unit, he explained, not because it could be shown to be valid, but because it was hoped it would be so.

Broady elaborated on the British case, where the cohesion observed in low income areas was attempted in planned communities:

Of course people do meet each other and chat in pubs and corner shops. But not all pubs and corner shops engender… neighborliness. It is true that neighborliness is induced by environmental factors. Of these, however, the most relevant are social and economic rather than physical.

—Maurice Broady, “Social Theory in Architectural Design,”Robert Gutman, ed., People and Buildings, (New York: Basic Books, 1972), p. 174)

In 1952, the especially perceptive Catherine Bauer summarized how early planners often failed to understand the broader forces at play in the urban development process, or innocently overlooked the consequences of their actions:

What we failed to see was that the powerful tools employed for civic development and home production also predetermine social structure to such an extent that there is little room left for free personal choice or flexible adjustment. The big social decisions are all made in advance, inherent in the planning and building process. And if these decisions are not made responsibly and democratically, then they are made irresponsibly by the accidents of technology, the myths of property interest, or the blindness and prejudice of a reactionary minority.

(Catherine Bauer, Social Questions in Housing and Town Planning (London: University of London Press, 1952), p. 25)

Implementation today

Do we risk overselling smart growth, placemaking or other urbanist concepts today, without taking heed of social and market realities? Absent large swaths of single-entity ownership, redevelopment of our current urban landscape is not easy — with limited raw land available for straightforward public or private sector-led development without sophisticated mitigation solutions.

Today’s urban redevelopment is often beset immediately with particular expectations or requirements to help solve urban and regional problems such as affordable housing and transportation. As these are elements of cost, a developer — in multiple international contexts — must find a way to contribute to resolution of these issues with the allowances of the project pro forma. Allocation of public or private funds towards provision of transportation and affordable housing infrastructure and/or mitigation must be balanced against design and constructability decisions (constrained site construction and demolition challenges, quality of building materials, lighting, etc.), allocations of uses, parking and open/street spaces and vegetation.

The bottom line? Today’s prescriptive goals for successful communities — not so different from those of the last century —r equire reality checks against the challenges of design, equity, regulation and financing, and must be addressed at an integrated and practical level worldwide.

After all, as Olmsted said long ago, beware of selling urban success using only the language of Utopia.