Great idea: Traditional neighborhood development

In celebration of the upcoming CNU 25.Seattle, Public Square is running the series 25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism. These ideas have been shaped by new urbanists and continue to influence cities, towns, and suburbs. The series is meant to inspire and challenge those working toward complete communities in the next quarter century.

Traditional neighborhoods developments (TNDs), inspired by historic neighborhoods, jump-started the New Urbanism in the 1980s and 1990s as alternatives to conventional master-planned communities. They were and are laboratories of ideas, creating pockets of community and urban space by overcoming legal and institutional barriers to holistic development.

TNDs revived long-neglected building types like accessory dwelling units, mixed-use and liner buildings, and brought back the front porch and rear garage. Walkable streets designed for slower-moving traffic were fought for and built. Many of the TND developers are now focusing on smaller infill projects, but new complete neighborhoods continue to be built in this market where financing allows and where sites call for large-scale transformation.

Public Square editor Robert Steuteville interviewed Vince Graham, president of the I'On Group, the developer of numerous TNDs and urban infill projects in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, including the Charter-Award-winning I'On in Mount Pleasant, and Katie Selby Urban, cofounder of Charter-Award-winning South Main, a town extension in Buena Vista, Colorado, on traditional neighborhood development.

You both have worked on neighborhood-scale, new urban projects—could you describe your projects, briefly?

Urban: South Main is just shy of 40 acres in downtown Buena Vista, Colorado. It was the former site of the town dump, but I wouldn't consider it brownfield, because it was mainly surface trash. This piece of property connects the river to the historic downtown, which in the past the town turned its back on, hence the trash dump. When we found the property, there was an offer in to make it a timeshare resort, so my brother and I, as kayakers, wanted to do what we could to make the river a public park. We hired Dover, Kohl & Partners and did a TND (traditional neighborhood development) there, with a whitewater park, trails, and climbing boulders. We subdivided off and donated the river corridor to the town, to make it permanently public. Then with funding from lottery funds in the State of Colorado, called Great Outdoors Colorado, along with a lot of fundraising and different partnerships we made the whitewater park happen.

Graham: Our biggest project, I’On, located in Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, is a 244-acre neighborhood. It's surrounded by developments from the '50s through the '90s. DPZ and Dover-Kohl worked on the original master plan and acted as advisors. We started over 20 years ago. The original vision called for 1,240 homes, 90,000 square feet of commercial space, and a dozen civic sites. Of those 1,240, I think 440 were slated to be multi-family. Through the political campaign to get the zoning, we had to compromise at 762 homes plus 30,000 square feet of commercial and about 10 civic sites. The first home was completed in 1998, a three-bedroom, two-bath 1,800 square foot house that sold for $160,000. Today that house would sell for about $800,000. The market demand for the neighborhood has pushed prices up so the median is now over $1,000,000. There's two churches and clubhouses. There was a Montessori school, but they were oversubscribed so they had to find a bigger location outside the neighborhood. There's about 30 parks in the neighborhood and 5 different types of thoroughfares.

But essentially it's an entire neighborhood that's now completely built out, correct?

Graham: No, there's about five acres of undeveloped property. There's still a few residential lots that lack houses, and several of the civic lots lack structures. It'll evolve over time, and things will be torn down and rebuilt. In 2010 or 2011, the town of Mount Pleasant passed an ordinance to enable accessory dwelling units. Before that, there were some black market units, but since then, that's opened the door for the construction of around 80 to 100 accessory dwellings.

Did you both have an overriding goal with these projects? And how well have you succeeded?

Urban: Initially, our goal was to build a whitewater park. I come from an environmentalist background and never imagined myself as a developer. When I joined my brother on the project I said, "Look, if you want me to be a part of this, we're going to do some research to figure out the most sustainable way to do it." So we went to the Rocky Mountain Institute for some consultation and they encouraged a new urban direction. We also happened upon Prospect New Town, in Longmont and came across the book Suburban Nation in the library—almost as if by chance—within 24 hours of each other. All that set us on a path. We were driving through Prospect, and we asked ourselves, "Why are we driving? We should walk." It was an epiphany that development could be more than what we grew up with, the sprawl of Tuscon, Arizona. Afterward, connected with Dover, Kohl, but we certainly didn't start out with that intention of building a TND.

We're still early in this project. We found the property in 2003 and we were entitled in 2006. In a town of just over 2,000 people, the workforce is really small, so the pace can sometimes be a little slow. We put in 40% of our infrastructure up front, even though phase one only included 15% of the lots. We're still finishing that phase off. We have the park, the trails, and we're starting to build up the commercial center.

Graham: I developed I’On that in conjunction with my brother Geoff and father Tom. The stated purpose was to make our corner of the world a more beautiful place, through the creation of an enduring aesthetic with economic and social value.

But we also aim to make money. We wanted to demonstrate a stellar model of traditional neighborhood design. We take inspiration from all these beautiful places in low country South Carolina—Charleston, Savannah, and Beaufort—and try to combine lessons learned there with modern advances to build a new neighborhood. We're building all the infrastructure, not only the water, sewer, and storm sewer lines, but streets, sidewalks and parks. We also try to guide the development of private grounds, as to complement the public. You adapt your situation where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

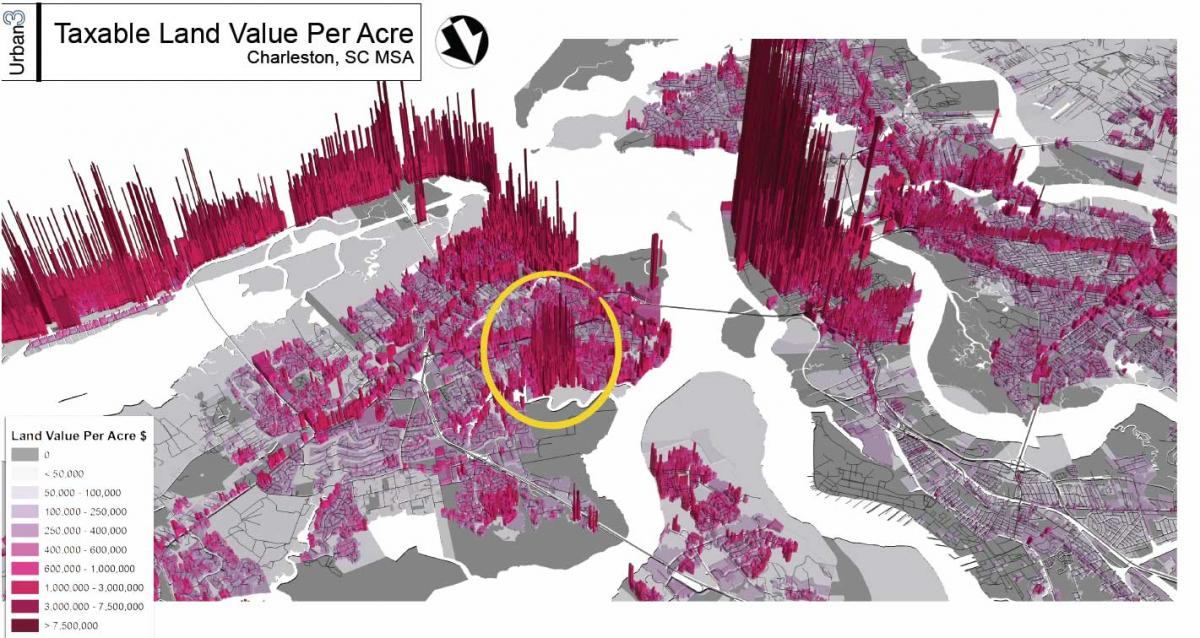

I recently saw a graphic, created by Joe Minicozzi, that showed land values in the Charleston area. I’on shows up as a peak, not as high as a downtown, but about as high as the ocean-front areas. Does that validate your approach?

Graham: I think what Joe's study shows, what we already all know, is there's a huge demand for this kind of neighborhood and a limited supply. That's what you see in these places that are well done. In my view, there's an increasing and accelerating demand for quality. And so if you can deliver that, then you create a lot of value.

How has that worked in South Main, in terms of creating value?

Urban: The prices are definitely higher than most of the surrounding areas. Sometimes, when we talk about it, it seems like keeping things affordable is tough when you're building really beautiful places people love. It's also a part of our goal as new urbanists. By making it more valuable, hopefully you can convince other developers to follow and build projects that are more enduring, loveable, and beautiful.

The New Urbanism began mostly with traditional neighborhood developments like Seaside and Kentlands, as well as I’On. They're on the neighborhood scale, and a lot of these earlier traditional neighborhood developments were non-city locations. Now there's much more infill and transit-oriented development. Have you seen a change in the New Urbanism, and if so, why?

Graham: It's more challenging, in my experience [to build in non-city locations] - and I haven't tried to do something like I'On in a long time. But with I'On or Newpoint, development already surrounded it. I'On is like a large infill site. Now, it's harder to get the development financing for projects the size of I'On. But an advantage of the infill-type development is it doesn’t require the creation of amenities. Katie and her brother have the river right there, but they've done so much to create the amenities, like we did at Newpoint or even at I'On. And so, that's certainly the advantage for infill, access to preexisting amenities. The popularity of cities has grown, and so there's more and more of these things [infill projects] within them. You don't have to create the whole neighborhood from scratch; you can build on to a neighborhood. But, once these neighborhoods are redeveloped, is it going to come full circle again and return to creating new neighborhoods from scratch? At some point, there won't be as many infill opportunities, but the way to deliver more affordability is to catch up with the demand. Create more supply and you'll keep the price in check.

Urban: Zoning codes are getting more progressive. For example, when we started South Main, the city went ahead and allowed accessory dwelling units (ADUs) by right on all of our residential lots. That added a good amount of density to the 315 units that we had already. What's nice about those ADUs is that they’re typically the place for affordable rental. Since then, the town has allowed ADUs for the rest its neighborhoods, a very progressive move. They're finally starting to see, "Oh. That's what they were talking about."

And for you, Katie, you've been working in the small town environment, and a lot of times people talk about urbanism, or New Urbanism, as being something that's happening in places like Portland and other major metro areas, but you're doing it in this town far off the beaten track. Do the same principles apply? Are you meeting a similar market?

Urban: When everyone says, "Oh, you're building a town," I always have a little bit of a reaction, because to me it's a neighborhood within an existing town. It certainly adds a lot of houses to the town, for sure. To add 315 dwelling units, plus 156 ADUs, to a town of 2,500 people, that's a huge increase over time. I think that's why it's been a slower process to build it out. Buena Vista luckily doesn't have a highway going through the historic downtown, so it's intact with late 1800s, beautiful historic buildings. The downtown Main Street is alive and thriving. Then on South Main, it's really interesting to listen to the conversations of tourists visiting there because they don’t realize the buildings are new. Our goal has been to blend South Main into the historic downtown and create one intact entity that's connected, perhaps a little bit separated, but surrounded by development to the south, town park land to the north, the river to the east, and the historic downtown to the west.

When Vince was talking, it reminded me a little bit about the history, and so I want to ask this question. Once upon a time, government would just lay out a street grid, and the land would be broken into appropriate size lots, and the neighborhood would be built. Do you think that that form of development can ever happen again?

Graham: I think that there's versions of that already. I've worked on projects where the local government will commission somebody like Victor Dover or Andres Duany or to come up with a master plan on a piece of property, and then they put out a request for proposals from developers to develop that property in line with the master plan. I think of the plan for Washington, DC. The federal government commissioned L’Enfant to design it, and then it built some of the streets. Governments are really the largest developers because they build all these roads.

And those roads set the stage for a certain kind of development.

Graham: That's right, they develop these roads and then they zone it for sprawl, and what do you get? I think people need to recognize that there's a huge industry associated with building sprawl which creates a lot of political patronage. Folks like Chuck Marohn and Joe Minicozzi have done great work to raise the level of awareness that this is not economically sustainable. So maybe it'll start to change.

Katie, is it changing?

Urban: I’m hesitant to believe it is. We’re starting to hear buzzwords like walkable and suburban retrofit, but the other day I was talking to a town planner and she said the town plans to be walkable and install sidewalks, but their zoning won’t allow commercial in the area. It’s my understanding that you have to have somewhere to walk to for it to be walkable. They’re using the word walkable, but there’s not necessarily that comprehension of what it actually means. But it’s a move in the right direction at least.

Another thing that you all have to contend with is a loss in knowledge and building practice. Is that changing?

Urban: For us it's changing because we've trained our subs. Steve Mouzon came out at one point and did training classes with our builders. Ultimately in order to keep things cost-effective not only for ourselves but for our buyers, we became the contractor and started South Main Building Company, the only builder in the neighborhood.

Graham. It's hard to deliver the quality or the detail that we once had, but the resistance to traditional form and local vernacular has been greatly reduced. Since Bob Turner and I started Newpoint, 25 years ago, there's a lot more architects and designers who are capable of working in a vernacular style. Elsewhere, there's a similar movement toward localism: local food, local crafts, etc. Maybe this trend in architecture is a part of a greater appreciation for authenticity and the local. Certainly, we've seen that in Charleston. These skilled young architects have an ability to be playful with the traditional forms. To use again the food comparison, the culinary artists in Charleston are making shrimp and grits, but it’s not how your grandmother used to make them. Again, they take the lessons learned from the local food and put their own modern spin on it. I see the same thing in architecture.

I'm sure you both have heard the criticism sometimes that entire new neighborhoods with Main Streets are like stage sets. Are you still hearing such criticism, and does this matter?

Graham: I've always felt that the criticism is somewhat unfair, because the places are brand new, so they're going to be shiny and polished. But at one time way back in the day, the main streets of Savannah were brand new, and with time comes a patina.

Urban: I think the truth is our culture is starved for walkable places that have an incredible sense of place, and so some people misrecognize it as Disney-esque.

You both have mentioned that you're seeing more smaller-scale development and that it's harder to finance big projects on a neighborhood scale. Do you see an ongoing role for this neighborhood-scale urbanism, and what is that role?

Urban: There is a demand and a need. It's happening. It's being built. The biggest challenge is overcoming not only the political will, but the will of the developers. I remember in the beginning I was determined to keep South Main affordable and Victor Dover looks at me with a smile and tells me I can help affordability via mechanisms in the New Urbanism, like accessory dwelling units, but ultimately, my job as a new urbanist is to show the other developers that this is worth doing from a financial perspective.

Both of you went through the housing crash, in a way. You both were developers during that time. How did you survive it?

Urban: It was really, really tough. We're a small company and it was always very low-budget. Because the crash happened right after we filed our first phase, my brother and I decided that instead of filing phase two and taking out another development loan, we would move forward with creating income-producing properties. We had just bonded with an irrevocable line of credit, had a legal obligation to install all that infrastructure within a year, and our property taxes had just skyrocketed once we subdivided all the lots into individual lots in phase one. At that point, my husband Dustin and I literally looked in an Allison Ramsay plan book, pointed to one, and decided to build that house and break ground in a month. We had to show that this neighborhood was still going to happen, and we'd only had one or two houses break ground at that point.

Graham: Y'all are brave. Good for you. We weathered the storm by going in the direction of smaller houses, still maintaining the quality, just smaller. The houses that got hit the worst were the larger ones. They got crushed. We didn't want to build anything that had to compete with the standard 2,000 or 2,500 square-foot house that was in foreclosure. We chose to try to offer something different on the market, and we worked slow and positioned ourselves for a more hopeful future. We took our licks and lost some money in other projects we were getting involved in. But we're still on that track of smaller projects.

I don’t know if you two are going to be involved with any more TNDs in the future, but I wanted to get your thought on what the next development in TND going to look like. Is it going to be any different? What do you think?

Graham: From our standpoint, the neighborhoods that we're involved in now are a little more organic looking, like the medieval neighborhoods in Europe, or the older parts of Boston or Charleston, where there’s less of a rigid grid, but still a network of streets. A lot of the newer plans that I've seen are pretty rigid with similar lot types, all 50-foot lots or whatever. We're trying to be much less formulaic and more… picturesque is perhaps the right word. More like Camillo Sitte and less like John Nolen.

The project we're working on now, Earl's Court, is able to achieve 30 units per acre of single family detached. And with Catfiddle Street downtown, it's closer to 40 or 50. Now, that has a bunch of ADUs mixed into it but I think there's some advantages to a less formal urbanism, to be able to achieve those kind of densities in a human scale, with buildings that aren't monolithic. It's easy to get densities way up there when you have these big, monolithic buildings, but that's not our bag.

Urban: From my perspective, people are very into the story of things right now. At least in my world—I live in Oregon, and sometimes it feels like the show Portlandia. You go into a coffee shop here, and it's all about where the bean are roasted, and who grew them. I was thinking about this the other day, in relation to South Main and what made it such a unique story, and what came to mind is Serenbe in Georgia, with its organic farm, and its farm to table movement, and things like that. I think that if I ever were to do another neighborhood development it would be on a much smaller scale. Even though South Main is small by a lot of standards it's a lot to take on and I still have a lot of work to do there. I would focus more on smaller infill projects.

Any final thoughts?

Graham: We’ve gone through a pioneering period. The pioneers get the arrows, but I think whether it be Katie and her brother, or Robert and Daryl Davis, or whoever, they blaze a trail for the future. Katie mentioned the change toward more perceptive zoning. I think there's great hope for the future. At least for the next 10 to 25 years I see the future as infill, both in the inner city as well as the suburbs. Last week, I was invited to this conference in San Francisco, where we talked about the future of the interstate system. They discussed all these innovative programs to tax automobile transit and improve automobile infrastructure. But in my view, what they're basically talking about is how to build a more efficient mousetrap, not a new mousetrap. What we really have to do is take the Interstates out of the cities. It would free up so much potential value and create so much potential new development if we were able to remove them from urban land.

Note: CNU intern Benjamin Crowther helped to produce this interview and article.