Supporting evolving Central Social Districts

Public Square editor Robert Steuteville interviewed economic development expert N. David Milder of DANTH, Inc., on Central Social Districts. Milder wrote a paper that was recently published in the American Downtown Revitalization Review. This is Part 2 of a two-part interview. See Part 1.

RS: What are the best ways that public officials can nurture (Central Social Districts) CSDs? Are there different strategies and tactics relative to place?

NDM: A lot of what we might want public officials to do will depend on the CSD venues that are targeted for development or expansion and local conditions. However, there are two things that I’d like to ask of city officials, downtown leaders, and stakeholders: 1) Be much more aware of CSD elements and their importance to the health and well-being of your downtowns, and 2) Please think strategically and comprehensively about them.

I’ve found that when public officials in small and medium sized cities turn their attention to downtown or Main Street revitalization it usually focuses on retail, and then too often on attracting retailers they never will get. Sometimes they will help a particular CSD establishment to open or expand. They may even leap for a proposed revitalization silver bullet like arts development.

Unfortunately, they seldom think comprehensively or strategically about how to grow and leverage their CSD assets. The daytime population in these towns is usually made up of active seniors, adults taking care of preschool age children, school children, and people working in the town. Some may also have tourists. The leaders in these communities need to think more about how to develop or cultivate CSD venues that can attract and leverage these market segments. Doing that also can help create venues that might be authentic and attractive to tourists. In my travels, over many decades, I have noticed in too many of these towns a lack of anchoring public spaces, poor programing of those they have, and a failure to attract other CSD uses (for example restaurants, senior housing, day care centers, libraries) to abutting storefronts that can generate significant daily visitor traffic. These spaces too often have poor locations on a side street or along the perimeter of the downtown. Also, as Andy Manshel so strongly advocated in his book, Learning From Bryant Park, effective programing is essential. Simple things like seating and shade are often inadequate.

In larger cities, their very size can create challenges to nurturing the CSD and fostering its positive impacts on Central Business District (CBD) elements. This problem is less likely when the downtown organization is responsible for the entire downtown or most of it. Those organizations are far more likely to have an informal or formal strategy that includes elements aimed at nourishing and growing CSD venues and that understands how that will impact positively on the CBD. Dallas has done a wonderful job of developing its housing, public space, and arts assets to immensely strengthen its downtown. Center City Charlotte took down its overstreet network, developed a large number of housing units in and near the downtown, made office buildings far more permeable at street level, and added a lot more outdoor dining. City and Business Improvement District (BID) leaders knew what had to be done strategically. Happily, over ten years its main corridor’s sidewalks became busy and vibrant, rather than empty and dreary. Philadelphia’s Center City District also has, since the early 1990s, cultivated and developed enormously strong CSD assets such as housing, restaurants, arts and culture venues, and many vibrant public spaces. It is noteworthy that its leader, Paul Levy, looks closely and has concerns about not only his district’s formally designated area, but also about what he calls the Greater Center City area that includes very important arts museums and parks. Of course, the BID in Manhattan’s Downtown CBD famously had a very successful strategy to create and grow CSD assets, especially housing, even to the extent of converting older and out of date office buildings into a substantial number of residential units.

BIDs tend to have interests and programs that are limited in number and type, and many kinds of CSD venues will not be covered by them. In large CBD dominant districts, the residential populations are nowhere near as important for BIDs as property owners and businesses. While they may try to recruit retailers, restaurants, and food markets they are far less likely to be concerned about pamper niche operations (e.g., salons, gyms, spas, martial arts studios, etc.) or senior and childcare facilities.

With the pandemic stripping these districts of the office worker and tourist market segments their retailers and eateries had relied on, several turned to trying to recruit local and regional residents as customers. Unfortunately, there is relatively little housing in the Midtown Manhattan CBD’s core area, and lots of strong retail and eateries in the Upper East Side and Upper West Side residential areas where the CBD’s retailers wanted to increase their penetration. Unless significantly more housing is developed in and near the midtown’s core, attention to many CSD venues is unlikely to grow in these BIDs.

RS: How does nurturing a CSD in a historic center differ from building one from scratch?

NDM: Save for new cities, I don’t see it useful to frame building from scratch as a key issue, since that often carries with it the question of how many venues are needed to establish a CSD. Instead, I think it’s much more useful to postulate that even one venue establishes a CSD, and the key question is how it can be made bigger and better. At the individual business level, restaurants, bars, and pamper niche operations are the easiest to develop as demonstrated by what happens in our smaller communities. Often downtown leaders think about major projects to strengthen their entertainment offerings such as renovating an old theater, developing a new museum, PAC, or arena. Among these possibilities vibrant parks and public spaces provide by far the best bang for the buck.

RS: How are CSDs changing in the 2020s due to social, cultural, or technological trends?

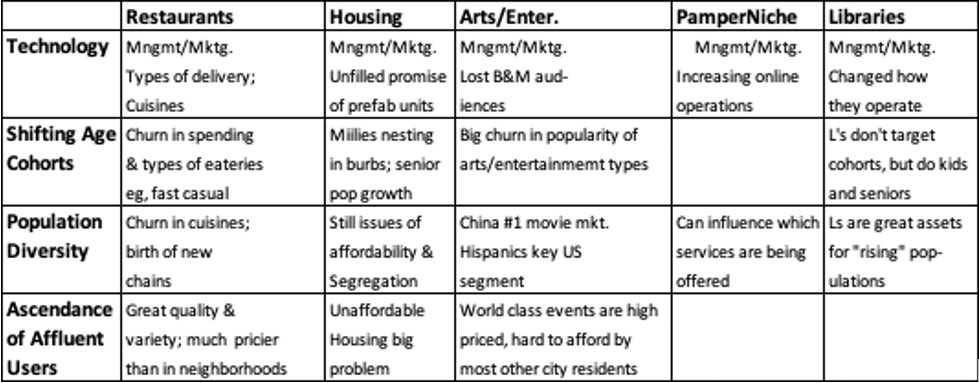

NDM: An adequate response to that question might require an article or even a monograph of its own. For the sake of brevity, I’ll confine my remarks to five types of CSD venues and four trends—see the table below.

Technology. As is the case with almost every other type of downtown operation, the ways that CSD organizations are managed and marketed has been profoundly changed and strengthen by the computerization of operational tasks and the use of the internet for marketing. As Pew surveys have shown, we now search the Internet before we do so many things, whether it is to shop in a retail store, go to a restaurant, or decide which movie theater to go to and when. The size and importance of this impact cannot be underestimated.

However, technology has had some very large impacts that are very specific to particular types of CSD venues. For example, the greater use of computers has enabled libraries to change from book repositories into information dissemination-based community centers that help local residents and businesses. They can help local inhabitants become citizens, find health services, learn about computers and the internet, learn English, find jobs, etc. They can provide small businesses with vital information, spaces to meet with clients, or access to special equipment in maker’s spaces. But technology has also made the electronic consumption of the arts soar, and reduced attendance at many brick and mortar performances and exhibitions. It is one of the major reasons some kinds of arts venues face uncertain futures. Many museums are making their holdings available online, and some opera and dance companies have special streamed performances to local theaters. However, I think their ability to generate significant revenues remains to be proven. Since the advent of TV, movie theaters have had to cope with one major technological innovation after another. The pandemic unleashed the issuing of new releases to the streaming services on the same day as they are released to theaters. Whether the same day releases prevail as we recover, and how much that will hurt brick-and-mortar cinemas remains to be seen.

The advent during the pandemic of app-driven meal delivery services, click/phone and collect meals, and curbside pickups promise to change the ways that a lot of restaurants operate. A corollary is the growth of ghost kitchens that provide food to be delivered under a number of brands, and have no dining rooms, just kitchen spaces. The labor shortage in the restaurant industry has also reinforced interest in the use of AI and robots.

Several of the pamper niche operations, especially those involving some form of teaching, were able to go online during the pandemic. For these “Amazon proof” operations, that also usually also have low start up and build out costs, the online presence may make them somewhat financially stronger. It could also reduce their demand for space.

Shifting age cohorts. The aging out of the Baby Boomers, the maturing of the Millennials, and the growth of Gen Z are all impacting CSD venues, especially housing, the arts, and restaurants. Mostly they work through changes of consumer taste and preferences. I think that most important is the fact that Millennials are climbing their career ladders and now nesting, with those living in large urban areas having a significant propensity to move to the suburbs when nested. The high culture art forms such as opera, ballet, and symphonic music attract audiences that are predominately elderly. Their audiences may well be aging out. Huge complexes, such as Lincoln Center in NYC and Disney Hall in LA have been built around these high culture art forms. On the other hand, “entertainments” like salsa music, rap, and country music concerts remain very popular, and all signs indicate a huge amount of pandemic caused pent up demand for such performances.

The different age cohorts also have had different restaurant preferences. The Millennials, for instance, like to eat out often, but they are not crazy about white tablecloth restaurants, preferring fast casual instead. Even before the pandemic the restaurant industry was going through a stressed period, and the need to adapt to the growing importance of Millennials was one of the causes.

Population diversity. The US has been a nation of immigrants from the start. Coming from numerous nations, cultures, races, and languages, immigrants brought or made here many things that are today essential parts of our culture and everyday life. Where would we be without:

- Pizza, hotdogs, salsa, tacos, pastrami, bagels, wonton soup and egg rolls croissants, red wines, pure malts?

- Or jazz, the blues, rock and roll, rap, folk and country music, classical ballet?

Many of the CSD’s arts venues and eateries showcase such products. In many instances the associated tastes and preferences have had a rate of adoption and cultural impact that is disproportionate to the populations of the ethnic and racial groups from which they come. Italians represent about 5 percent of the US population, Jews about 3 percent, and Blacks about 13 percent, but it’s a safe bet that most Americans enjoy pizzas, bagels, and jazz, the blues, or rock and roll. That is an indication that it has been relatively easy for various ethnic and racial groups to impact on our culture, and the products produced by our CSD venues such as restaurants and arts organizations. Where their influence probably has been weaker is on who is working, performing, managing, and owning in these industries, i.e., their share of the associated economic power.

That imbalance of impact today is joined by the fact most demographic experts agree that in the near future White Americans who largely descend from European immigrants will become the minority. The US will be a “minority majorly” nation with the majority composed of people of color: Hispanics, Blacks and Asians.

The emerging minority majority is reflected in changing tastes and preferences, such as the reduced popularity and prestige of Italian and French restaurants and the growing popularity of Asian and Middle Eastern cuisines. Hispanics now account for a significant percentage of moviegoers in the US and attract the attention of studio execs in their production decisions. And there are international tie-ins: the huge markets in China and other Asian nations are now a major force in setting the production agenda of American movie studios and production companies. I doubt that we are anywhere near seeing the full impacts of population diversity on our cultural and entertainment tastes and preferences.

Atlanta is a city that I plan to look at more closely in the future. It has developed an interesting downtown, Blacks hold significant political power, and there seems to be a kind of Black business and cultural renaissance occurring in the city.

Ascendance of affluent users. This trend worries me the most because I think it poses a serious long-term political danger to our large CSDs and their downtowns, When I came up in the downtown revitalization field back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, revitalized downtowns were heralded not only for their potential central place business functions, but also for their potential central place community functions. Moreover, they were thedowntown, thecentral place for the entire city or town, they were everyone’s neighborhood. Back then, the danger was that they were turning into decaying crime-ridden ghettos for the poor and the powerless. How we revitalization advocates then strived to bring more affluent people to our downtowns!

Times certainly have changed. Today, our large superstar downtowns are strong ghettos of the rich and very rich. Residential housing in and even near their cores are unaffordable not only for the normal middle class, but even for many able to pay $1 million for a new home. Middle income residents can work in the downtown, but unless they share a unit, they are very unlikely to be able to live there. Not only can’t the middle class live in these downtowns, but it’s also hard for them to even play there. The high prices in their restaurants inhibit frequent use, and the costs of tickets to plays, concerts, dance performances, operas, etc., can be prohibitively in the hundreds of dollars in the primary market and in the thousands in the secondary market. To top it off, from 50 percent to 88 percent of the admissions in Manhattan’s world class entertainment and cultural venues are tourists. More and more locals feel they do not belong in such places, where those from away seem so obviously preferred. Also, more city residents who do not live in and near big downtowns are shopping, dining out and enjoying entertainment venues closer to home—or in their homes. A big signal about this occurred during the pandemic, when a very important group of retailers in a famed Midtown Manhattan corridor decided to try to attract city residents—a market segment that previously held little of their attention—to make up for the tourist and office worker shoppers they had lost. Department stores in Midtown since at least the late 1990s have had 50 percent of their sales coming from tourists.

Thankfully Midtown’s parks and public space offer the average Joe and Jane some affordable, easily accessed places where they can relax and play.

Mesh this with the growing diversity in the populations of these cities, and the future of these downtowns becomes more uncertain. In such a scenario if the city leaders have to choose between say a needy neighborhood and hurting Lincoln Center, the latter would have a significant chance of losing. NYC’s battle about the Amazon HQ2 project is a forerunner of such a scenario, and the dismal results of the hoity toity Hudson Yards project has added another motivational stream for their eruption.

I have nothing against having a lot of wealthy people working, living, and playing in our downtowns. But strong efforts are needed to make the CSD and downtown visitor and resident mixes much more heterogeneous than what they are now, if they are to properly perform their citywide central place roles, and maintain widespread political support among city residents. Of course, I’d argue with equal strength that it’s also just the right thing to do.

See Part 1 of the interview.