Seaside is a model of ideas worth spreading

As I sit here writing this article at Seaside, I enjoy the convenience of being able to walk to the places I want to visit during my days here. I appreciate the beauty of the buildings and the way that they relate to one another—such that I feel like I am walking through a series of beautiful outdoor rooms as opposed to simply walking down a street. The native landscape provides an informal, comfortable setting that helps me relax. My kids happily roam the neighborhood as free-range children. And depending upon my mood, I love having the freedom to hang out in the bustling town center where I can watch the theater of life as people come and go, or take a short walk to my front porch where I can enjoy a tranquil setting that is perfect for reading a great book.

If I go back nearly 40 years to the start of Seaside, what I describe above would be considered nothing short of radical. In fact, Seaside was so revolutionary for its time that it either pioneered or popularized more than a dozen ideas that had not been applied in the context of post-World War II real estate development. Today these ideas continue to influence those who seek to develop places people love.

1. Town founder. Before Seaside, a developer was nothing more than a developer because developers were only attempting to create subdivisions, not real towns. Seaside's town founders, Robert and Daryl Davis, aspired to create a holiday town that had all of the charm and vitality of an Italian town such as Portofino. Beyond the intention to develop an authentic town (which has the characteristics that are mentioned below), they decided to live in the town and manage it as a canvas upon which others could paint their dreams. These three elements remain the most important ingredients for developers who aspire to create a place that people will love.

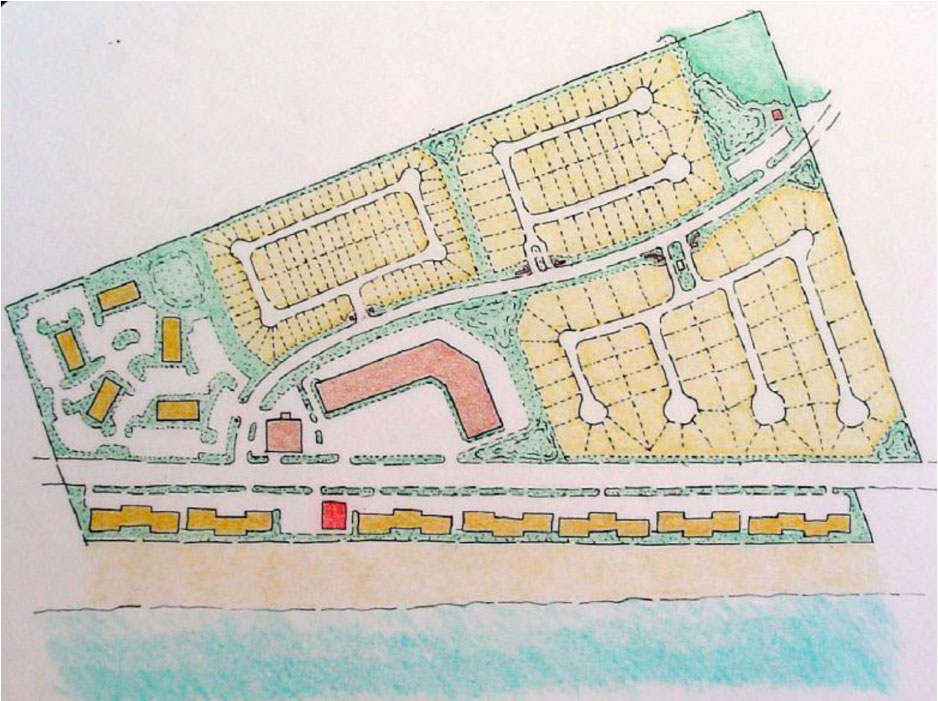

2. Incremental development model. When you are building a real town, it takes a very long time for the primary amenity—the convenience, liveliness and charm of a town—to be built. Thus, land in a town appreciates greatly between the beginning and end. A conventional subdivision, on the other hand, does not appreciate nearly as much because the primary amenities, such as the house, a view or a recreational amenity, are delivered in the beginning. That is why the conventional real estate development model is premised upon building and selling lots and/or buildings as quickly as possible, even if it means borrowing a lot of money to support the fast pace. Robert Davis restored the traditional development model which is ideally suited for towns because the profits primarily stem from the appreciation in land values, not the speed of sales, and the flexibility for going slower comes from developing incrementally (thereby avoiding debt). The most obvious manifestation of this incremental approach was the fact that Seaside developed one street at a time, going from east to west. It should go without saying that this low-debt incremental development model produced greater returns than the conventional model could have.

3. Interconnected network of walkable streets and paths. Before planning Seaside, the town founders, along with the town planners, Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk (“Duany Plater-Zyberk”), methodically studied and measured the most beloved coastal towns. This research made it clear that the streets should be modest, and that the streets should intersect frequently—resulting in small blocks. Small blocks slow traffic so people feel more comfortable walking or biking. They also make walking or biking more interesting because it provides many different ways to get from point A to point B. Despite the historic success of this approach, Seaside was a pioneer for abandoning the large block/disconnected street model of the day in favor of an interconnected network of walkable streets and paths.

4. Connecting to surrounding development. While designing streets to frequently intersect was considered radical at the time, it was even more radical to design the streets to directly connect to the land that surrounded the development. Duany Plater-Zyberk not only designed Seaside so that it would connect to the existing streets in Seagrove, but also to the undeveloped land behind Seaside (which is now WaterColor). This approach adds life to the town center and makes getting in and out of the town more convenient. It is now a common practice to design street connections to surrounding development even if the the actual connections are not built in the near term.

5. Integration of civic spaces and buildings on prominent sites. By the 1980s developers segregated civic uses such as schools, churches, post offices and parks from residential development. At the same time, they usually placed these uses on leftover parcels that were inexpensive to purchase (while selling off the best land in the development to individuals). Seaside returned to the historic model of towns by reserving the most prominent sites for civic uses that could be enjoyed by everyone. At Seaside, each street that leads to the beach terminates in a community pavilion; the chapel is aligned so that it terminates the view from the heart of the town center; the school is placed so that it connects to the town center as well as the surrounding neighborhood; and the largest community gathering spot is the amphitheater at the town center.

6. Integrated mixed use. Like civic spaces and uses, in the early 1980s developers segregated commercial areas from residential areas. Seaside opted for the historic model which provides shops and restaurants within walking distance of all of the homes in the neighborhood. This provides convenience for everyone. In addition, when people are living above the businesses, it makes the town center much more vibrant during a wider range of hours.

7. Live-work units. Historically, one of the most affordable models for starting a business in a town was to live above or behind your business. These are commonly referred to as "live-work units." Seaside revived this building type by designating live-work units around Ruskin Place. Combining residential and commercial uses was so rare at the time that some of the buildings had to be financed without making it abundantly clear to the lender that the first floor would be used for commercial purposes.

8. Retail incubation. By the 1980's retail development consisted of strip malls, shopping centers, regional malls and large stand alone stores. What was missing were the historic small-scale retail formats that foster the creation of new start-up businesses (due to their low cost). Town founder Daryl Davis revived those affordable historic models by incorporating temporary and seasonal retail formats in modest structures like tents, one room temporary pavilions, kiosks, airstream trailers, etc. Indeed, downtown Seaside essentially started as what is now known as "pop up" retail in the form of a Saturday market. These formats not only serve as an effective business incubator for the town, they also add life and flavor to the Seaside experience.

9. Successional development. When Seaside began, developers built structures with the assumption that they would not be replaced or moved within the next few decades. This approach has three drawbacks: (a) it prevents a town from evolving over time as market conditions change; (b) it delays the introduction of businesses or amenities during the early years of a town (when a town does not have adequate market demand for them); and (c) it reduces the number of entrepreneurs because it greatly increases the cost of starting a business. Seaside rejected this approach in favor of the historic practice of fostering successional development; i.e., development that could change over time as the town matures. Examples of structures that have been built at Seaside with the expectation that they would be moved or replaced as the town grows include the Per-spi-cas-ity market pavilions (which is now Cabana by The Seaside Style), the learning cottages at the Lyceum, the motor court, and the non-masonry town center buildings.

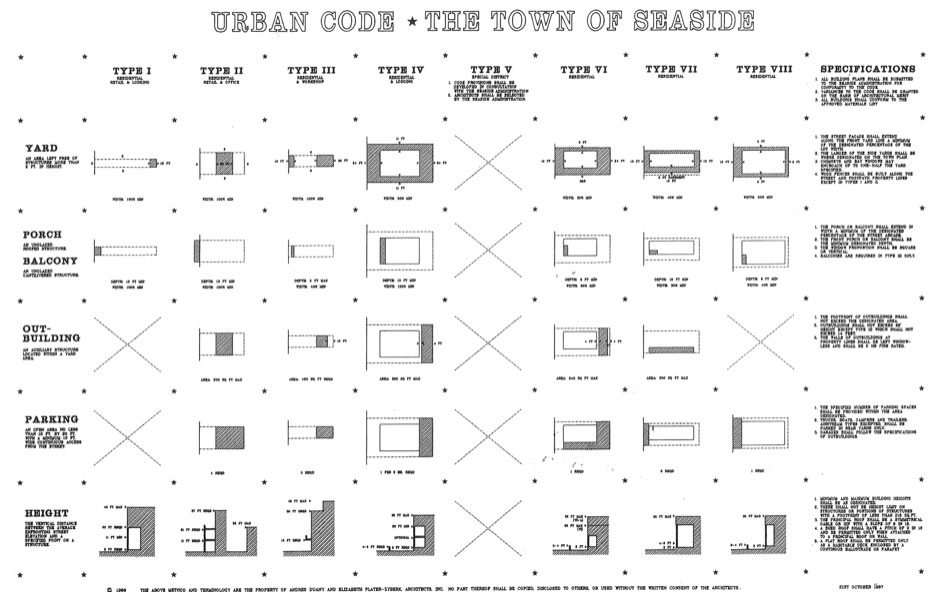

10. Form Based Code. A form-based code is a type of zoning code that focuses primarily on the form and placement of buildings as opposed to the use or density of the buildings. Because a form-based code does not ignore issues that greatly impact the character of a place (such as the minimum building facade width on a lot), they produce development outcomes that are much more predictable. Duany Plater-Zyberk developed the first form-based code for a new town—a simple one page, graphically-illustrated “Urban Code.” Today, form-based codes can be found in hundreds of communities across the country.

11. Town Architect. In the early days, Seaside’s embrace of traditional architecture drew more attention to Seaside than anything else because: (a) it was a stark departure from the typical architecture one would find in a new development; and (b) it was easy to see and understand (before the town center emerged). Equally important, since 1983 Seaside has engaged a town architect who oversees and helps guide the character of the town. Many other traditional neighborhood developments have adopted this approach because, in conjunction with the Urban Code, it has been effective at generating quality architecture from builders, designers and architects.

12. “Many hands” variety. One of the primary objections to conventional subdivisions is that they feel “cookie cutter.” This stems from the lack of diversity of building types (i.e., everything is the same size) and the small number of designers involved in the projects. Duany Plater-Zyberk made sure that Seaside would avoid this mistake by: (1) developing the Urban Code which mandates a variety of building types; and (2) making sure that “many hands” (i.e., designers) contributed to the character of Seaside. To date, more than 150 designers have contributed to the design of Seaside.

13. Original Green. The master plan and the choice of architecture at Seaside both reflect traditional methods for achieving a high level of environmental performance. For example, to help mitigate the impact of the summer heat, the master plan has streets running perpendicular to the shoreline so that prevailing breezes reach deep into the neighborhood. At the same time, houses have: (a) deep porches, overhangs and trees to provide abundant shade; (b) metal roofs to reflect the sun; and (c) raised foundations to cool the underside of houses. Using traditional methods to improve environmental performance is commonly referred to as the "original green" as coined by Steve Mouzon's book by the same name.

14. Xeriscaping. Xeriscaping is the planting of native plants that require minimal water and maintenance. Douglas Duany developed a planting code for Seaside that requires native plants everywhere except for a few formal spaces such as the amphitheater, Lyceum Lawn and Forest Street Park in front of the chapel. This environmentally-friendly practice wasn't even given a name until 1981-- the same year that Seaside started. Due to its economic and environmental benefits, it is now a common development practice.

15. Light Imprint infrastructure. How a developer manages heavy rains might not be the sexiest element of the development process, but it greatly impacts the immediate and long-term costs to the developer and residents. The conventional approach favors building an extensive network of drains and underground pipes to channel water away from the neighborhood or to water detention areas that must be constructed on site. Seaside opted to minimize the need for the conventional pipe infrastructure with two primary techniques: (1) designing and building the amphitheater so that it could also serve as a detention area for water during unusually heavy rain events; and (2) reducing the number of impervious surfaces that prevent rain from infiltrating the land where it falls (e.g., streets made out of brick so that some of the rain can drain in place; on-street parking areas made with gravel instead of asphalt; raised foundations that allows water to drain under houses). These traditional techniques (along with many others) later became known as the "light imprint" approach to infrastructure as set out in Tom Low's book "The Light Imprint Handbook."

16. Non-profit institute. The Seaside Institute is a non-profit organization that seeks to promote educational and cultural activities. In 1996 it started hosting seminars that served as the primary way that developers learned how to develop traditional neighborhood developments. It celebrates people who have had a major positive impact on how we build our communities by giving an annual Seaside Prize award. It has supported cultural activities by incubating a number of arts programs including Escape to Create which is an artist-in-residence program that draws artists and visitors to 30A during the off-season. Developers of other traditional neighborhoods have established similar non-profit organizations that also seek to support programming that relates to the core values of their towns.

Many places would be happy if they served as the model for one or two ideas, but Seaside continues to serve as a model for more than a dozen ideas that were nothing short of radical at their inception—not bad for a funky little beach town, but not surprising given the amount of love, care and expertise that was put into it.