Texas city adopts street grid and code

Bastrop, Texas, adopted new, groundbreaking land-use regulations in November that address flooding and establish a street grid as a framework for growth—one of the first cities in the US to do so since the middle of the 20th Century. The Bastrop Building Block (B3) code is the result of the Building Bastrop initiative, launched in August 2018 with the goal of creating fiscally sustainable, geographically-sensitive development that is authentic to the city.

“We started this process last summer to address flooding in Bastrop and create a roadmap for responsible development that honors our authentic past and prepares for our sustainable future,” said Bastrop Mayor Connie Schroeder. “Like many cities and towns across the country, Bastrop has been faced with tough decisions related to significant growth combined with aging infrastructure and outdated land-use regulations. With Building Bastrop, we are controlling growth rather than letting growth control us.”

Bastrop is a fast-growing small city about 30 miles southeast of Austin. This decade Bastrop was struck with five floods of the Colorado River—two from 2015 to 2016—and another this year, in addition to three significant wildfires. Resilience to nature is not the city’s only immediate concern.

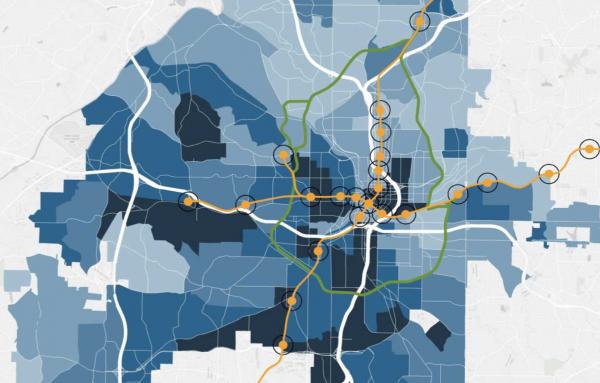

Bastrop recently conducted a fiscal analysis of revenue per acre and productivity. The analysis, by the Dallas firm Verdunity, looked at whether each parcel in the city was “revenue positive,” measuring return-on-investment of the city’s development patterns. Like many cities, Bastrop has grown in a “drivable suburban” form. “The current development is not fiscally sustainable. We’re $7.2 million upside down now,” says City Manager Lynda Humble. “The goal is that everything built at least pays for itself going forward.”

Adding to concerns over environmental and fiscally sustainability—city leaders want to grow in a way that is compatible with the city’s history, character, and culture. Bastrop was founded in 1832, with 131 buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

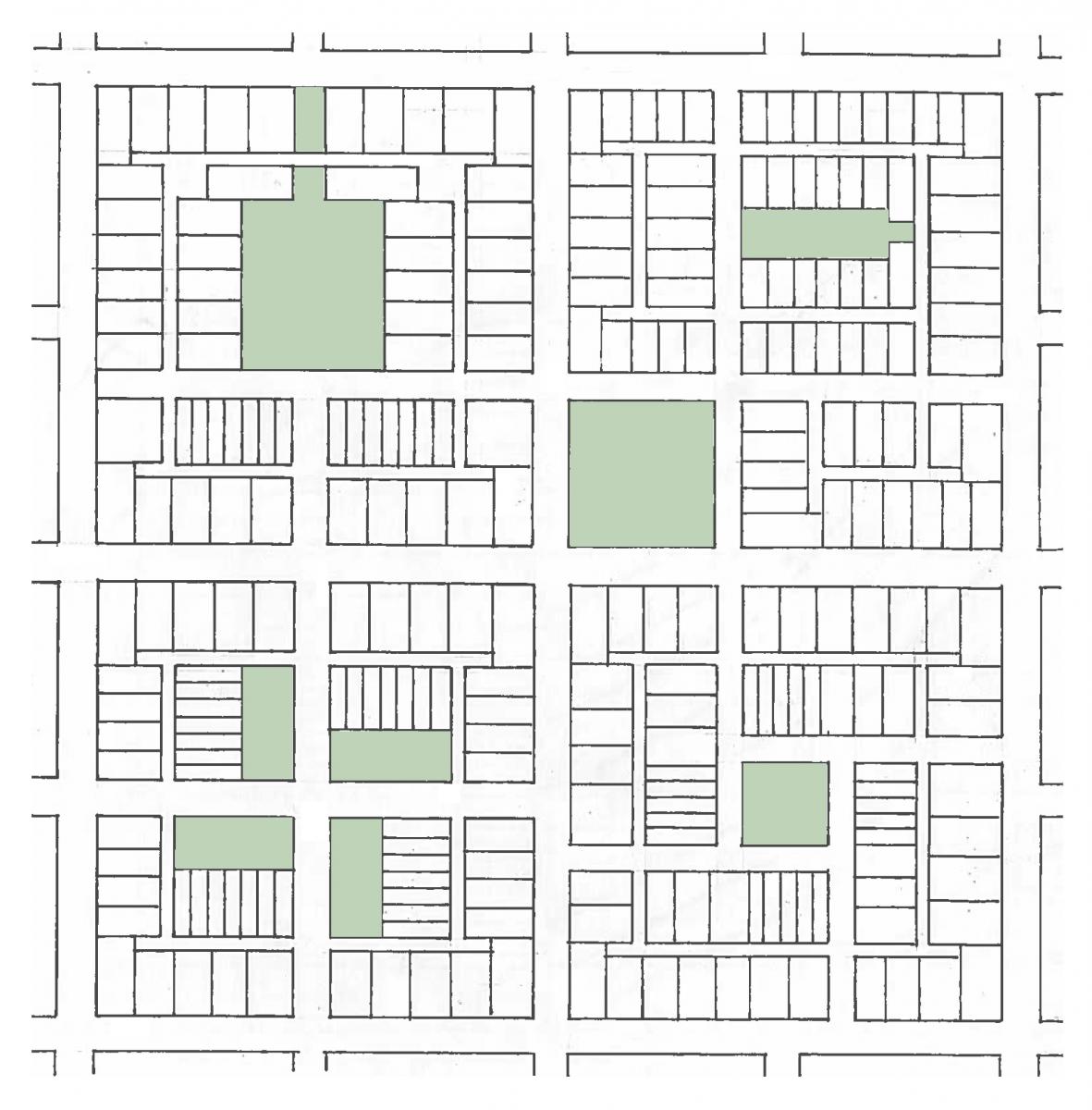

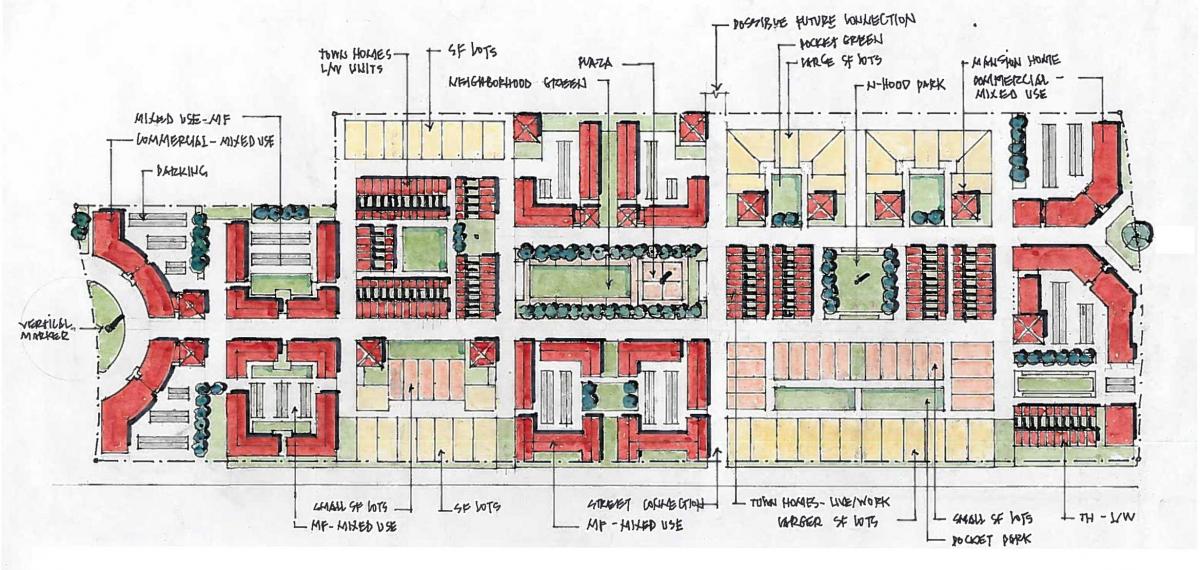

To find answers, Bastrop looked at the built part of the city that has survived for more than a century. The city hired Simplecity Design based in San Marcos, Texas, to “analyze the DNA” of downtown. “We found the solution to our problem is under our nose,” says Humble. “It’s downtown Bastrop.” The urban designers found that the square downtown blocks are a quarter the size of historic farm lots. Farm lots could therefore be divided into four “Bastrop Blocks,” which can be configured in many ways—all of which have built-in stormwater capacity.

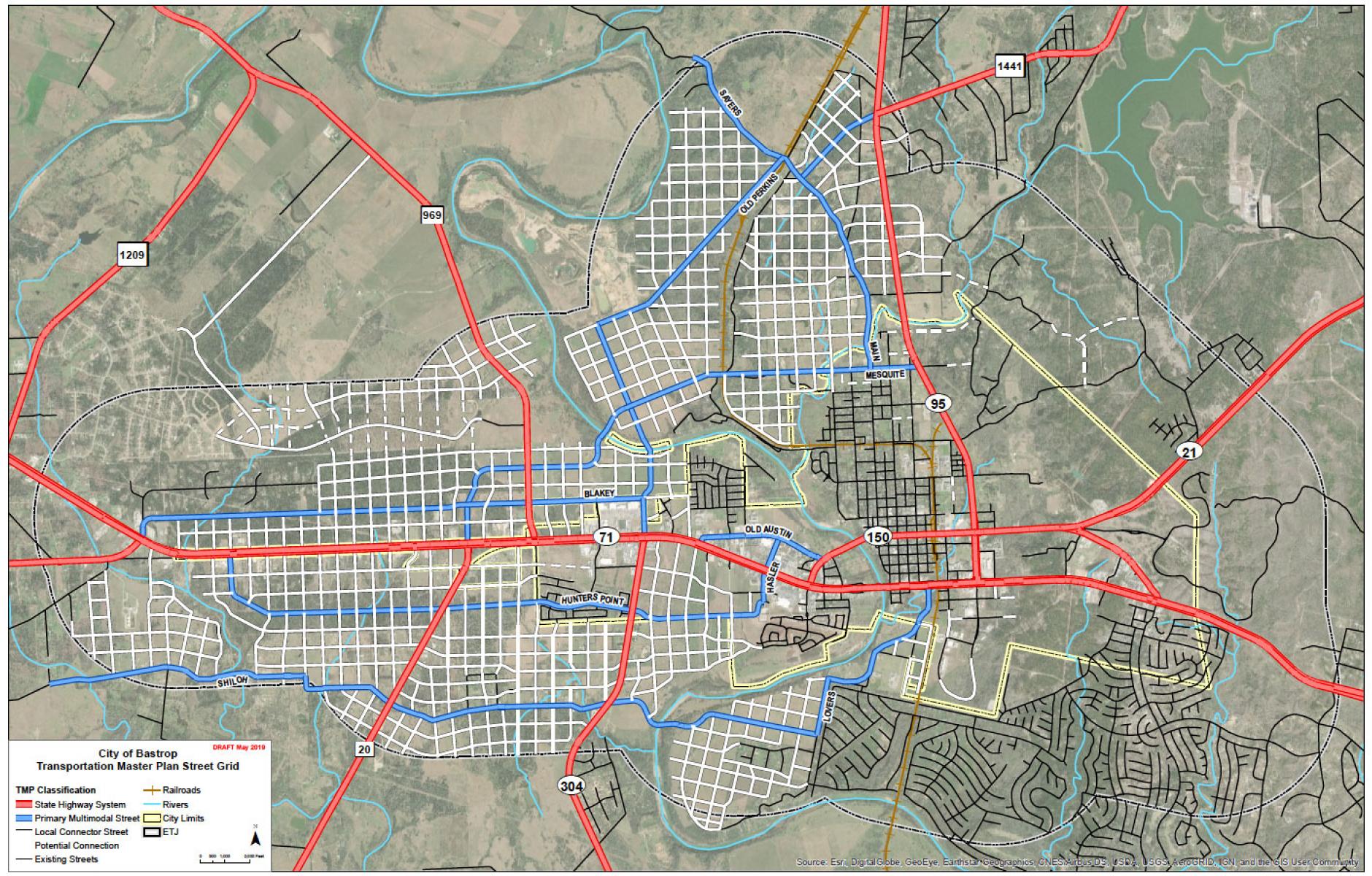

The city is therefore determined to grow, like downtown, in the form of a grid—one that responds to geography and nature. The city adopted a Transportation Master Plan that establishes a street grid not only in undeveloped parts of the city, but also in an extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ), for which the city has transportation, environmental, and subdivision controls. “We had to have gridded streets in order to have fiscal sustainability,” Humble says. The grid is based on 770-by-770-foot farm lots, which are divided into four 385-foot blocks (330-foot-square plus the right-of-way), the Bastrop Block. “Some areas don’t allow for grid due to natural geography,” Humble says. “Where the land will accept a grid it’s the primary mode.”

The new code is very lean—based on the rural-to-urban Transect, it does not regulate uses, only nuisances. The thinking is that if the use creates no problem, why regulate it? There are no minimum lot dimensions or parking requirements. Shared parking is encouraged. Every lot is automatically allowed to have two accessory units. So, rather than the continuing the single-family zoning that is fiscally unsustainable as a dominant pattern, every lot can have three units.

The Bastrop Block is designed to address stormwater drainage. There are many pre-designed versions of the block that serve as models for developers to choose. Every one of them deals with its own drainage—so new development will never add to the stormwater problem.

All American cities grew in the form of a grid until about 1950. That grid system was abandoned all at once, all over America, in favor of a dendritic network with branches that lead to arterial roads, like the trunks of trees. These arterial roads tend to be large—and that makes them difficult to cross and walk along. The main thoroughfares often become congested. Charles Marohn, in his recent book Strong Towns, notes that the development patterns based on this system tend to have low value per acre and they have trouble supporting the infrastructure required.

Very few cities have gone back to the grid—only one other that I am aware of has adopted a similar plan. That’s Laredo, also in Texas. Maybe with these pioneering examples, other cities will consider this policy.

In addition to the grid, the city mapped “place types” throughout the municipality. These place types relate to intensity of development and building types. They determine how the code can be applied. If the developer simply follows the place types and uses the thoroughfares that go with these types, they can get administrative approval for plans. The place types respond to geography and nature of the city—so the code responds to many conditions throughout the 9.4-square-mile city. The city has bluffs, flatlands, river flood plains, and a forest of loblolly pines that is 100 miles from any similar environment. The latter area is known as the “Lost Pines.” Bastrop also has an endangered toad, the Houston Toad, that needs habitat protection.

Says Matt Lewis of Simplecity Design: “The city determined that the one-size-fits-all code could be replaced by character districts, place types, and street types that tie back to the history of the area. It’s a holistic code, with development, streets, parks, preservation, and building rules all in one document.”

The code also changes the way the city deals with Public Works, Humble says. The previous approach focused on plenty of concrete and asphalt, which isn’t the best approach for dealing with stormwater. The new code is more flexible in allowing pervious pavement alternatives, like crushed granite and soil, and open swale approaches to drainage. No parking requirements and shared parking will reduce asphalt.

The city took a bold step in August 2018 to enact a development moratorium. The city had a good reason—flooding. Since that time, the city has not stopped development—more than 600 permits have been issued. Yet development has been steered in a new direction. Every part of the new regulations were debated three times—leaders asked whether each part leads to fiscal sustainability, environmental sustainability, and is it “authentic Bastrop?”

Substantial public engagement in the form of workshops and a charrette led to strong community support, says Humble. Bastrop is also seeking to alleviate the us-versus-them relationship between developers and public officials.

“Most cities don’t take this journey,” she says. “We have a bold council willing to have bold conversation on what was wrong and what it takes to fix it—they never wavered.”

City Council member and Mayor Pro Tem Lyle Nelson adds: “As a city, we have a responsibility to put policies in place that support the community for generations to come. We’ve had a clear vision from day one, and our new land-use regulations are the result of 15 months of diligent work by our staff, consultants, boards and commissions, with input from the community every step of the way. The B3 Code is a reflection of community feedback and priorities, including walkable neighborhoods with a variety of housing options, improved accessibility and mobility, and responsible development that ensures neighbors aren’t flooding neighbors.”