Mapping the culture and retrofit of a car-oriented community

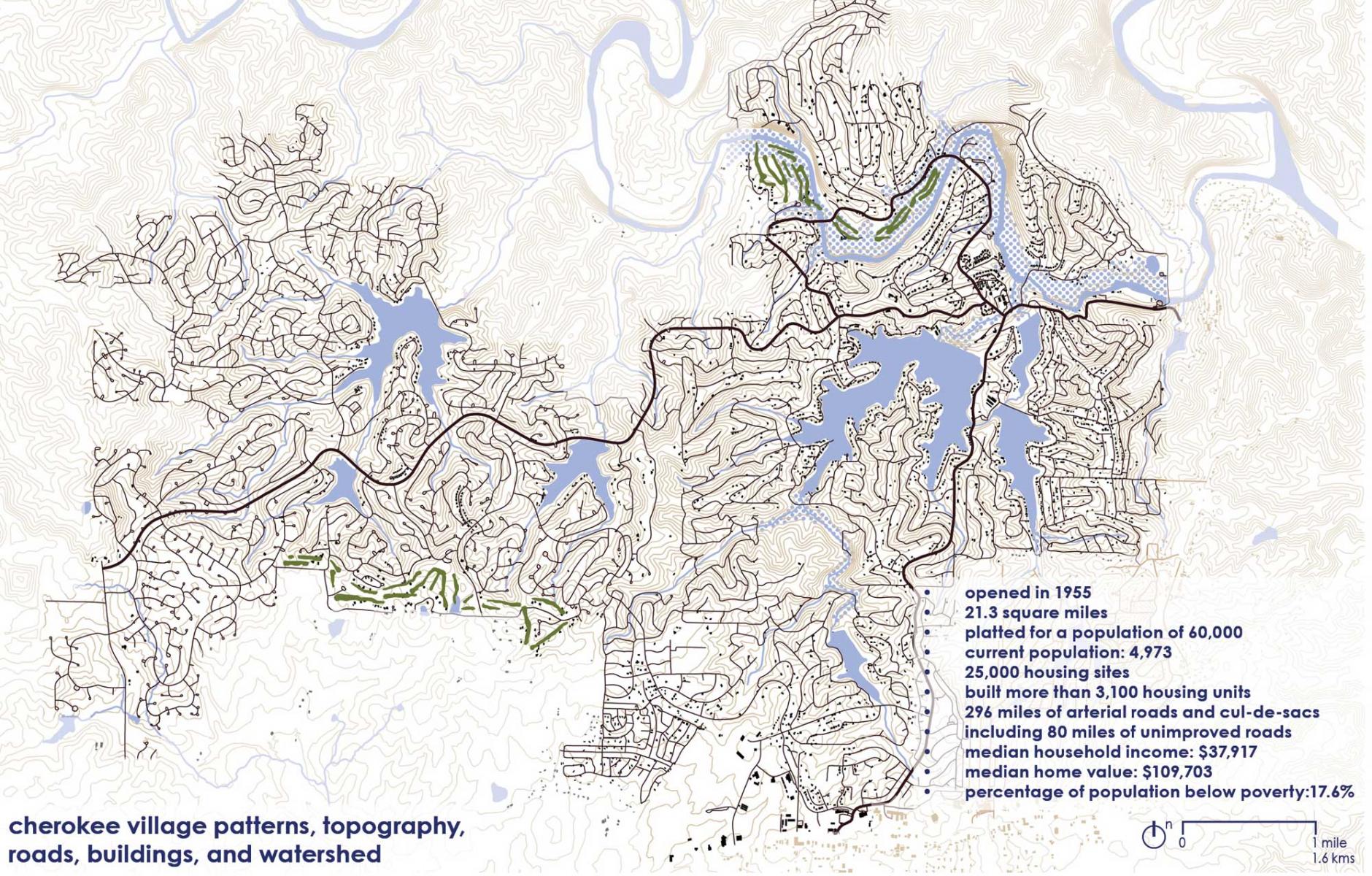

Cherokee Village is a mid-20th-Century planned new town that failed to reach its full potential. After 70 years, only 20 percent of the lots are built, housing a population of about 5,000 people. It was planned for 60,000 people, served by nearly 300 miles of roads over 21 square miles of northern Arkansas.

“The Framework Plan provides a model vocabulary for how urban design and planning culture may approach the retrofit of midcentury automobile-oriented community planning,” according to the University of Arkansas Community Design Center, which led the design team. “This plan is also distinguished by the incorporation of cultural mapping in its approach to both community engagement and planning.”

Cherokee Village demonstrates an unusual blend of rural living built on a conventional suburban planning chassis. Over the years, much of the village’s history was forgotten. Despite initially being designed as a new town, the village now lacks a planning staff and relies on outside consultants.

In 2020, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded Cherokee Village a coveted Our Town grant to undertake cultural mapping in support of a Framework Plan to guide future development. “The initiative was led by a local community developer and local nonprofits as a community advisory committee working on behalf of the City of Cherokee Village,” the Community Design Center reports.

“I'm optimistic that this document will serve as inspiration and hopefully will be a catalyst for the next important steps our city leaders will take toward creating a shared vision and workable plan for the Village's future,” says Jonathan Rhodes, Community Developer and Recipient of NEA Grant for Cherokee Village. The plan highlights the following concepts:

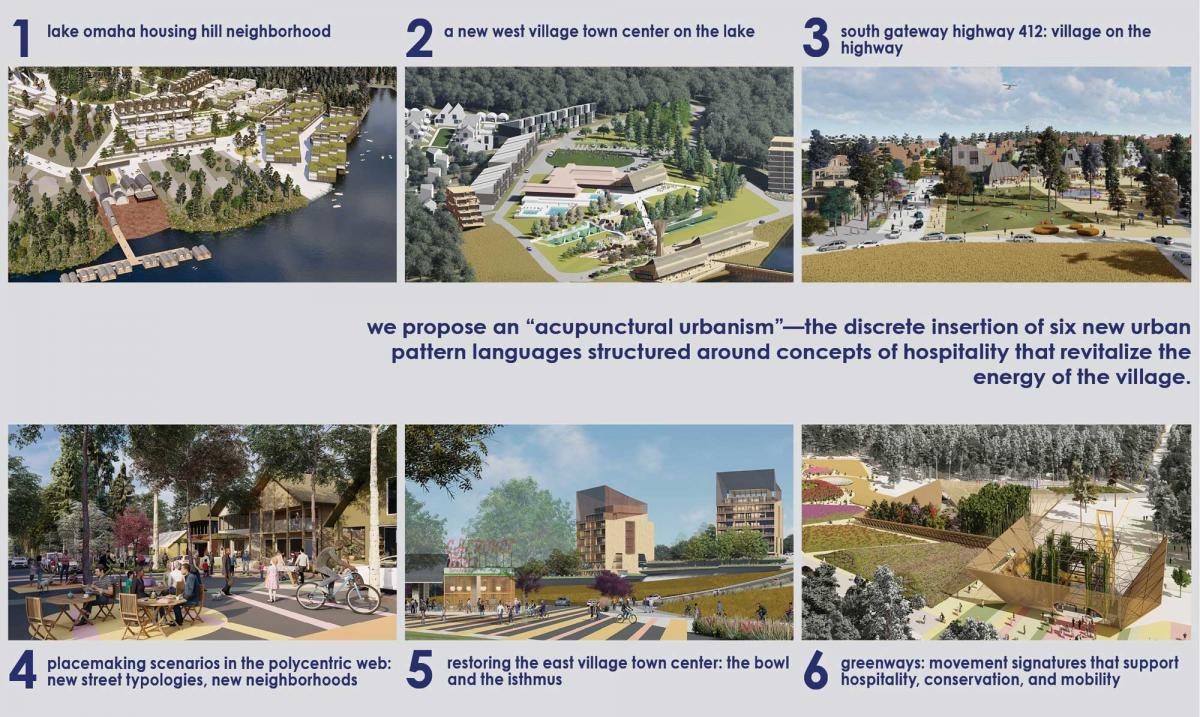

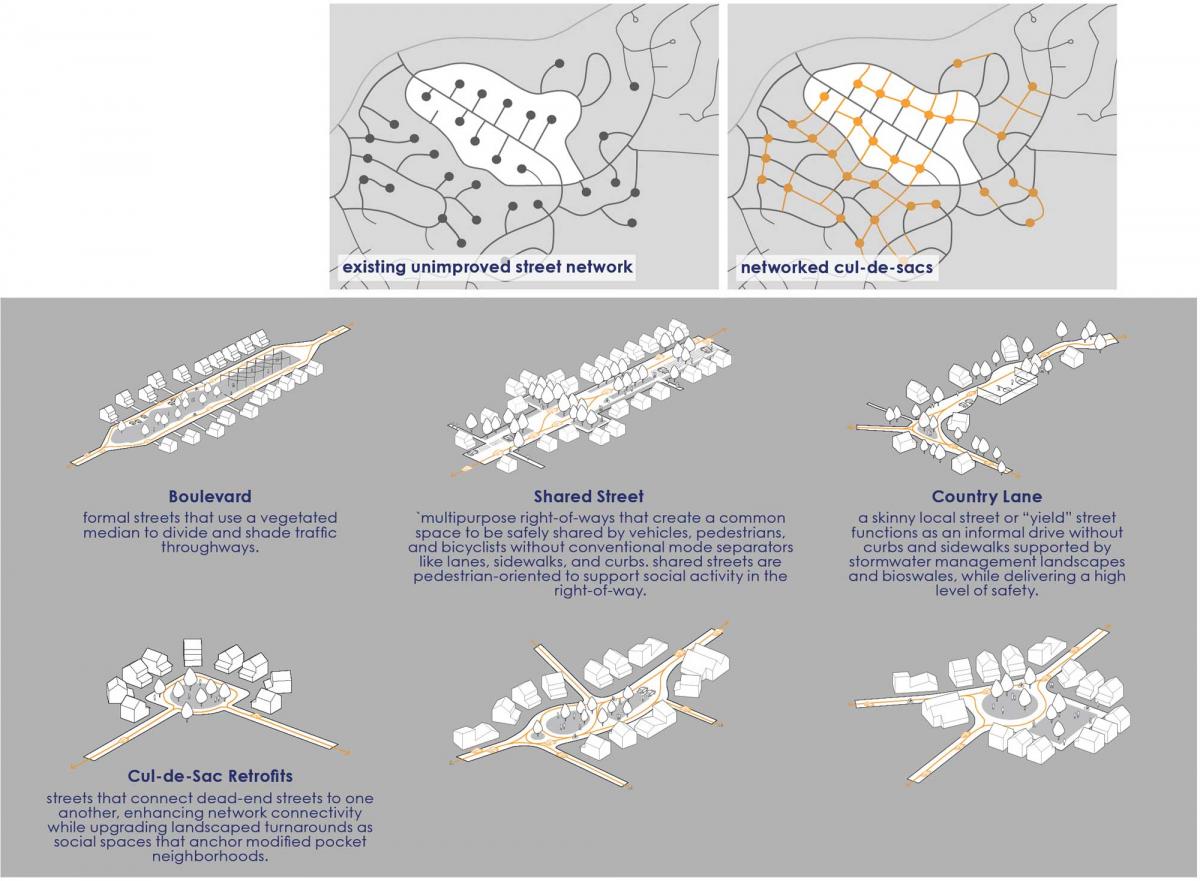

- Retrofit strategies. “One of the largest planning challenges facing us—and one for which we lack shared planning vocabularies—is retrofit of sprawling mid-century bedroom communities,” notes the design team. The plan uses pattern languages to “catalyze higher-order living environments” within Cherokee Village. Existing nodes are to be restored and reimagined; a new town center and gateway are planned, and poorly connected streets are to be linked. Placemaking scenarios are also being planned. Each of the strategies “recalibrates automobile-only fabrics through fundamental principles of walkability, mixed-use planning, use of identifiable typologies in buildings, streets, and landscapes, human-centered scales of development, and strong social orientations.”

- Diverse housing types, structured around hospitality landscapes for all incomes, lifestyles, and unit ownership tenures. More than a thousand housing units include “tiny trailers, tiny homes, cottages, mews housing, missing middle housing, apartment flats, live-work, and residential towers.”

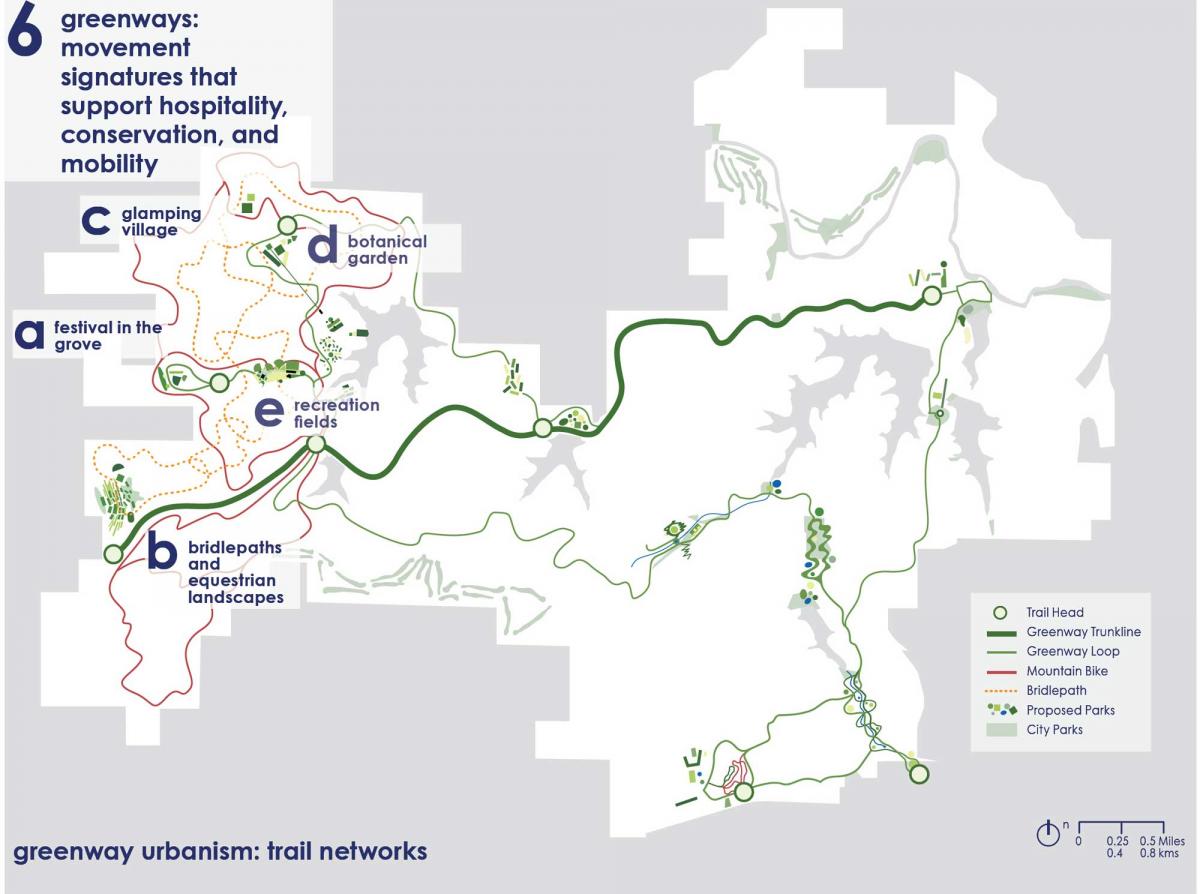

- Greenway urbanism. An alternative to automobile-oriented planning, Greenway urbanism employs a continuous network of paths and activity nodes accreted from three general conditions in the Village: 1) repurposing of unimproved roads—horses; 2) retrofitting of trafficked roads as living streets, and 3) developing a secondary independent trail network. The greenway network bundles ecosystem services with tourism, recreation, festival space, natural resource management (e.g., forest thinning to yield timber), and living and camp environments.

- Reprogramming of the polycentric web introduces the retrofit of cul-de-sac subdivisions as a set of connected micro-greens in a street network. New neighborhoods created from the retrofit feature “living street” typologies, such as shared streets and country lanes, premised on pedestrian-first connectivity.

- Cultural mapping. The plan explored five cultural forces that shaped Cherokee Village as identified by local stakeholders: Native American heritage, Ozark pioneer and folk heritage, camping and scouting, midcentury planned communities (an ambitious vision of developer John Cooper), and regional modernism in design and planning (the City has the largest collection of noted architect Fay Jones buildings in one place).

The cultural mapping process taught the Community Design Center a great deal. “We now view cultural mapping as an indispensable tool in reparative-based urban design and planning,” the team notes. Cultural mapping explores local cultural assets, stories, practices, relationships, memories, and rituals, according to communications expert Nancy Duxbury. “Cultural mapping is guided by participatory forms of inquiry, research, and representation into place in partnership with the community, very different from a charrette,” explains the planning team.

“The cultural mapping gave us valuable insight into our Village’s heritage that we had no idea about,” says Mary DeWitt, a member of the Project Advisory Committee.

The 2025 Charter Awards will be presented at CNU33 in Providence, Rhode Island, on June 12.

A Framework Plan for Cherokee Village, Arkansas:

- University of Arkansas Community Design Center, Principal firm

- City of Cherokee Village, Client

- Jonathan Rhodes, American Land Company, Community Developer

- Northeast Arkansas Regional Intermodal Authority, Project Partner

- Cherokee Village Visitor & Welcome Center, Project Partner

- Ozarka Community College, Project Partner

- Cherokee Village Historical Society, Project Partner

2025 CNU Charter Awards Jury

- Rico Quirindongo (chair), Director, City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development

- Majora Carter, CEO of Majora Carter Group in the Bronx, New York City

- Jake Day, Maryland Secretary of Housing and Community Development

- Anne Fairfax, Principal, Fairfax & Sammons in New York, NY, and Palm Beach, FL

- Eric Kronberg, Principal, Kronberg Urbanists + Architects in Atlanta, GA

- Steven Lewis, Principal, ZGF Architects in Greater Los Angeles, CA

- Donna Moodie, Chief Impact Officer, Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle

- Joe Nickol, Principal, Yard & Company in Cincinnati, OH