Benefits of urbanism outweigh costs

Miami, Florida, was the first major city to adopt a Transect and form-based code (FBC) for the entire City, called Miami 21, in 2010. A study by a West Virginia University economics professor provides evidence that Miami 21 is based on sound principles—that the benefits of urbanism outweigh the costs.

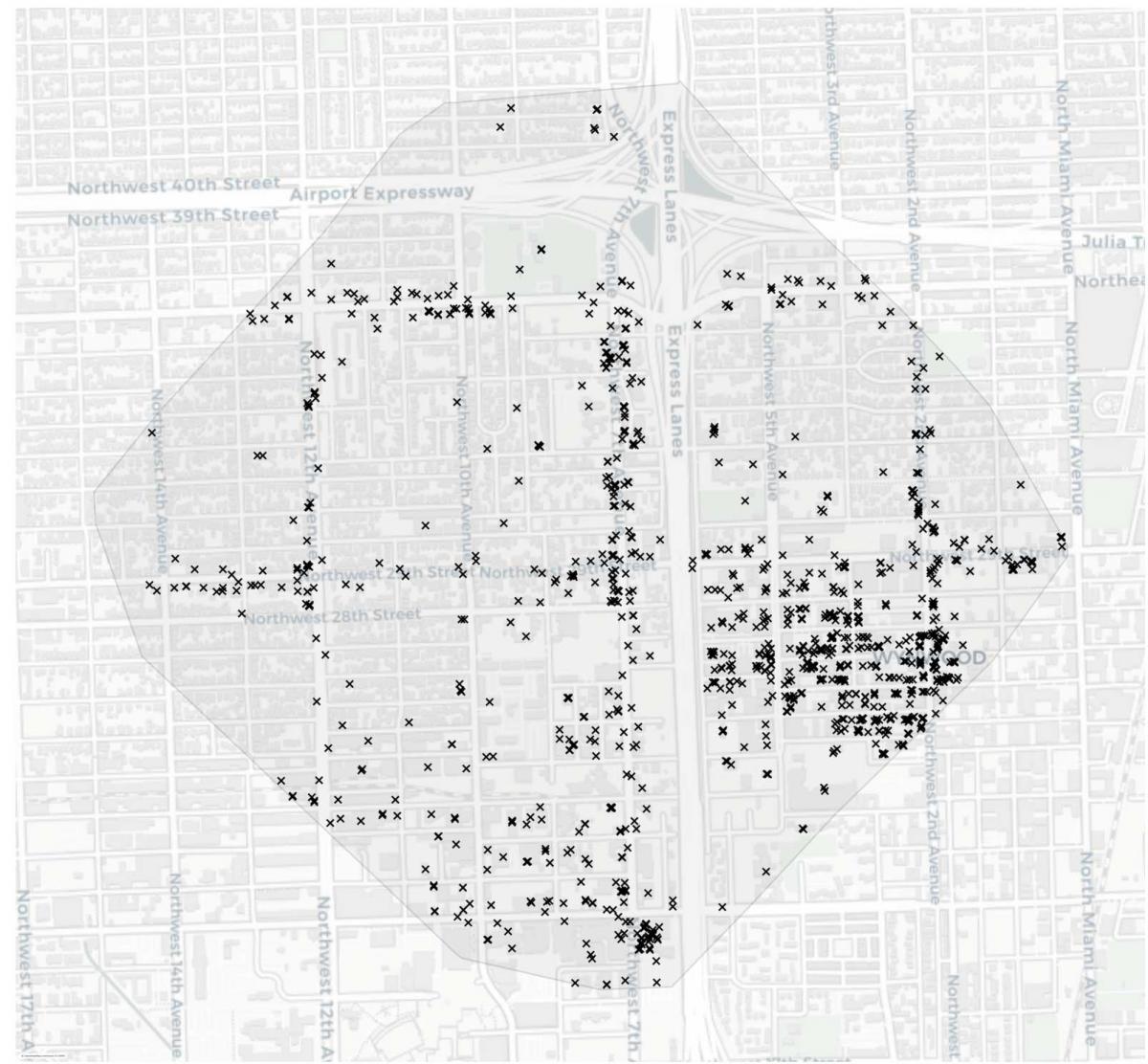

The study, “Estimating the Demand for Walkable Neighborhoods: Evidence from a City-Wide Zoning Reform in Miami, FL,” uses smartphone data to analyze how people move around their neighborhoods, comparing mobility to real estate values, crime, and other factors.

“I find that residents of Miami have a strong revealed preference for walkable neighborhoods,” writes Assistant Professor Terrence Jewell, the author. “The estimated willingness to pay for a one-standard-deviation increase in walkability is approximately $24 per square foot, relative to a median housing price of about $305 per square foot.”

Using smartphone data, Jewell determines the 15-minute walking sheds throughout the City and the destinations available within those sheds. More destinations within a neighborhood strongly correlated with more trips within the walking shed. “A 1 percent increase in access raises local usage by about 0.35 percentage points, indicating that neighborhoods with greater amenity availability experience more localized trip behavior,” he explains. Higher walkability allows residents to “combine multiple stops within a single outing —a behavior known as trip chaining.”

Jewell describes the adoption of Miami 21 as a “bold shift” away from a Euclidean zoning code—toward a FBC based on the SmartCode, an open-source New Urbanist code that could be tailored to fit any locality. “The SmartCode was developed by DPZ with many colleagues among the membership of the Congress for the New Urbanism, so it carried a certain amount of professional weight that allowed Mayor (at the time) Manny Diaz and (then-planning-director) Ana Gelabert-Sanchez to imagine that a city government and its residents could accept such an apparent drastic change to the regulations,” explains Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, co-founder of DPZ CoDesign.

It was, in effect, a bet on urbanism—which has economic benefits and costs, Jewell explains. “Cities thrive on density—but they are also constrained by it. Dense environments expand the range of consumption possibilities: a greater variety of shops, restaurants, cultural venues, and everyday services become accessible within shorter distances, lowering the time cost of daily life and enriching urban the experience. Yet the same proximity that enables this richness also brings costs—crowding, noise, traffic congestion, and crime that can undermine the quality of urban life (Glaeser, 2012; Duranton and Puga, 2020). Zoning regulations determine how density takes shape—where people live, work, and consume—and thus whether urban growth produces vibrant, mixed-use neighborhoods or low-density sprawl.”

Crime has a negative effect on real estate prices, according to Jewell’s measure—but walkability has an even stronger positive impact. The largest impact Jewell found, greater than walkability, is proximity to high-paying jobs.

Population growth in the City has accelerated significantly since Miami 21 was adopted. The city had 399,457 residents in 2010, rising 10 percent to 442,241 in 2020. Over the first four years of this decade, Miami jumped another 10 percent to an estimated 487,014 people in 2024. In other words, Miami did well demographically as Miami 21 was implemented and the City worked out the kinks of the new code. After that initial decade, the City has grown even faster.

A downside of this rapid growth has been rising prices. Miami is one of the pricier US cities, with average rental rates from $2,200 to $3,200 per month, depending on the data source such as Apartments.com and Zillow, according to a web search.

Miami 21 streamlined a cumbersome conventional zoning process while prioritizing placemaking concerns, such as activating sidewalks with pedestrian-friendly building frontages. “Rather than separating land uses—such as commercial, industrial, and residential—the city reimagined growth around walkability, mixed-use neighborhoods, and a compact urban form,” Jewell explains.

The city’s walkability depends on more than the code, Plater-Zyberk told Jewell. “In all fairness, the city’s grid structure (Thomas Jefferson’s mile-square continental grid was applied here a century after its first establishment) and historical walkable scale of streets and blocks made what you have measured as much possible if not more so than the code,” she says. “Pre-existing proximity might be considered a facilitation for the overall effort.”

In fact, Miami is nearly 100 percent built on a grid, with relatively small blocks, creating good bones for urbanism. Miami 21 is creating more useful destinations to walk to, in addition to the frontages that make walking more interesting—while allowing for development of compact housing types. Google Street View reveals that the City still needs to make walking more comfortable—particularly by planting shade trees that give pedestrians respite from the subtropical sun.