A pedestrian’s reckoning with a car-centric culture

Ten years ago, I experienced what felt like the worst punishment imaginable: my car keys were taken away. Not because of a ticket or illegal activity, but due to a medical condition that made driving unsafe. In a culture built around the automobile, losing access to a car was more than just a hassle—it felt like exile. I lost not only convenience but also the independence and freedom I had long taken for granted. Yet that forced transition—from the speed of driving to the slow rhythm of walking—has profoundly changed how I perceive the world.

Over the past decade, I’ve walked everywhere: to stores, appointments, social events, and work. Luckily, I live in a place where this is at least possible. Though the infrastructure isn’t perfect, it supports a pedestrian lifestyle—most essentials are within walking distance, though often inconvenient.

Although one sees people most everywhere in the environment of streets, walking is a brief journey, usually from a parking spot as close as possible to the entrance of the destination to that entrance and back. Few go far on foot. During my longer walks, I’ve noticed I rarely see the same person twice—evidence of how unusual my way of traveling is. But walking immerses you in your surroundings in ways driving never can. At a slower pace, the differences between beauty and neglect become sharply clear.

I notice the care my neighbors invest in their homes; that care communicates a sense of “pride of place” and “eyes on the street,” which, in turn, sends a message about pedestrian safety.

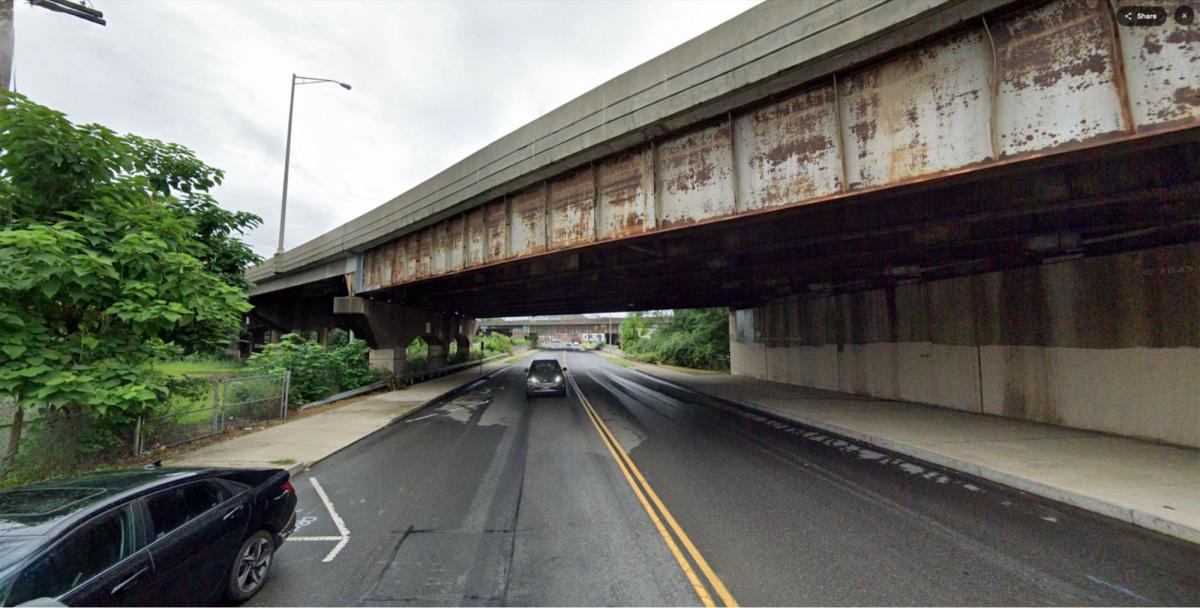

But walking out of necessity, not choice, also means exposure—to weather, distance, and above all, to dangers posed by wheeled vehicles. Long walks reveal not just charm, but also the harsh truths of how our streets are designed: for cars, not people. I remember some close calls; fortunately, they have been limited to being knocked down by a few cyclists so far. The rise of e-bikes, scooters, and skateboards indicates that encounters may become more serious. Even on sidewalks, pedestrians rank lowest. Everything is reversed compared to the walkability messages we often hear. From the dedicated pedestrian’s perspective, what’s praised in the name of pedestrian safety is more likely to advance the well-being and safety of vehicle operators. For decades, traffic engineers’ training has been limited to a focus on vehicle safety, not walking. They use the same road design standards for both streets and highways, setting twelve feet as the minimum lane width. This makes vehicle operators feel safe at high speeds.

One of the few engineers who challenge this is Rick Hall, who advocates for maximum lane widths, not minimum, adjusted down based on pedestrian proximity. Narrower lanes slow traffic and enhance safety—but they are rarely adopted.

The reason for minimum widths is that lane width determines “design speed.” By setting “design speeds” higher than “posted speeds,” engineers make driving safer at the lower speeds mandated by “posted speeds.” Ironically, the safety provided by higher “design speeds” encourages drivers to exceed the “posted speed” limit, testing their skills at high speeds.

To update old streets to meet modern design standards, cities introduced one-way streets, eliminated curb parking, and added turn lanes. Roundabouts remove left turns altogether and promote continuous traffic flow. Just painting a line to separate lanes boosts “design speed” by nine miles an hour. All these measures aim for one goal: to reduce congestion through faster traffic movement.

It was no surprise that traffic engineers quickly embraced bike lanes. Like car lanes, they are wide, direct, and fast—designed with familiar goals, but separated from the driving lanes, boosting their “design speed” as well. As a result, the lanes (not the bikes) are added measures to isolate pedestrians by increasing speeds for all types of vehicles.

Even features marketed as pedestrian safety improvements—like flashing lights, raised crosswalks, and curb bump-outs—often serve as visual cues for pedestrians to proceed cautiously, ironically giving another green light to vehicle operators.

These design choices come with a cost: over forty thousand people die each year in crashes. Unlike the tragedy of one death, forty thousand is just a statistic, minimizing resistance to minimum lane width standards. The cost of maintaining the same twelve-foot lane width on city streets results in an additional seven thousand pedestrian deaths.

Mechanization’s dismissive attitude toward pedestrians is deeply ingrained. The term “jaywalking” was coined in the early 20th century to shame those uncouth enough to cross streets mid-block, instead of walking to the end of the block and back to reach something directly on the other side. However, from a pedestrian’s perspective, crossing mid-block is often safer, offering clear sightlines and avoiding unpredictable vehicle turning movements at intersections.

Faced with hostile street designs, some walkers avoid busy streets and turn to fringe streets that escape modern "improvements." These sequestered streets are less direct, take more time to traverse, but feel much safer—even when you're walking in the middle of them.

Of course, the inconvenience of being pushed to fringe streets and the increased risk at busy cores can be frustrating, even causing anger. One shirtless cyclist, bristling with a “six-pack,” dismounted and challenged me to a fistfight for not walking to the side of the sidewalk. However, this anger subsides when one comes to realize that almost everyone, whether pedestrians or vehicle operators, feels anger on roadways. AAA and other groups like The Zebra and Nextbase report that over 80% of Americans admit to engaging in road rage and aggressive driving, both inside and outside populated areas.

Yes, our collective anger has many causes—political division, media echo chambers, economic and ethnic segregation. But the most significant and often overlooked factor is the decline in the daily routine of human connection. When we replaced human connectivity within neighborhoods and streets, we lost more than just walkability—we lost the opportunity to regularly interact with people outside our immediate circle.

This isolation fosters unnecessary distrust and hostility. Without the daily routine of face-to-face encounters—shared space and those small moments of eye contact, the frequency from which familiarity and interactions grow—we lose our ability to empathize with strangers. The literal takeover of public streets, which removes their vital role in fostering social capital and turns them into speedways for car-dependent consumerism, has proven unhealthy. The U.S. Surgeon General cites social disconnection as having a mortality impact similar to smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

Kurt Braddock, an assistant professor of public communication at American University, highlights that it’s impossible to overlook how polarization and the normalization of violence have become deeply rooted in the US. Referencing data from Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative, Braddock says, “We’re moving in a very dangerous direction, and I think we have been moving in this direction for quite some time.” Chuck Marohn, a self-proclaimed “recovering traffic engineer,” strongly agrees.

Inside a car, one can pass through blight and despair, often the default aesthetic of traffic engineering itself, without any sense of danger. But this insulation—this "cocooning"—also prevents the kinds of chance encounters that form relationships and build community. Without them, strangers remain strangers, and divisions deepen. Now, try to imagine yourself in the shoes of a solitary pedestrian passing through.

If we want to lower suspicion, distrust, polarization, anger, and unspeakable violence, we can’t continue to ignore the critical responsibility of street design. It's time to rethink the purpose of streets. Vehicles need access, but they should take a backseat to the more important goal: bringing people together.

Let’s stop designing streets only as transportation corridors and begin reclaiming them as shared spaces focused mainly on people, connection, community, and humanity.

Note: This article was published on smartgo.network/.