You can’t make a great city, without a great public realm

New urbanists often speak of the public realm—but what is it?

The public realm consists of streets, parks, and other public spaces where you can wander freely, ideally on foot. Think of the city as a series of connected outdoor rooms, large and small, bounded by buildings: That’s the public realm.

The frontages of the buildings are the walls of the outdoor rooms. The private realm is beyond those walls—the areas within buildings or blocks that are not accessible to the public.

This concept is quite different from how we have thought of cities since about the middle of the 20th Century. As cities grew after 1950, they still consisted of buildings, but the surrounding land was primarily accessible by automobile. Commercial buildings are often fronted or surrounded by parking lots, and garage doors are the most prominent feature of houses.

The conventional suburban city does not feel like an outdoor room, and “the public realm” is far too grand a name for automobile-oriented thoroughfares or parking lots. The city built after 1950 was largely private realm, surrounded by conduits for cars.

The new urban concept of “the public realm” implies an urban design that is radically different from conventional modern planning. Yet, it is time-tested through centuries of city building before 1950. Defining the public realm is essential because building a great city or town, even a great new urban town center, is inseparable from creating a great public realm.

The Charter of the New Urbanism is a valuable resource for guidance on the public realm. I would highlight three passages:

- Interconnected networks of streets should be designed to encourage walking, reduce the number and length of automobile trips, and conserve energy.

- A range of parks, from tot-lots and village greens to ballfields and community gardens, should be distributed within neighborhoods. (Covered in a different section of the Charter, regional parks are also part of the public realm).

- A primary task of all urban architecture and landscape design is the physical definition of streets and public spaces as places of shared use.

The first point clarifies that streets must be designed in such a way to encourage walking, and they must be connected in a fine-grained network. This improves mobility of all kinds, even driving, because it allows for almost unlimited choices in how to get around and the distances between uses are shorter with the compact urbanism that results.

While streets are the most common part of the public realm, the second point adds that a wide range of public spaces are provided within neighborhoods and regions.

Finally, architecture and landscape design play a critical role in shaping the public realm, both within streets and other public spaces.

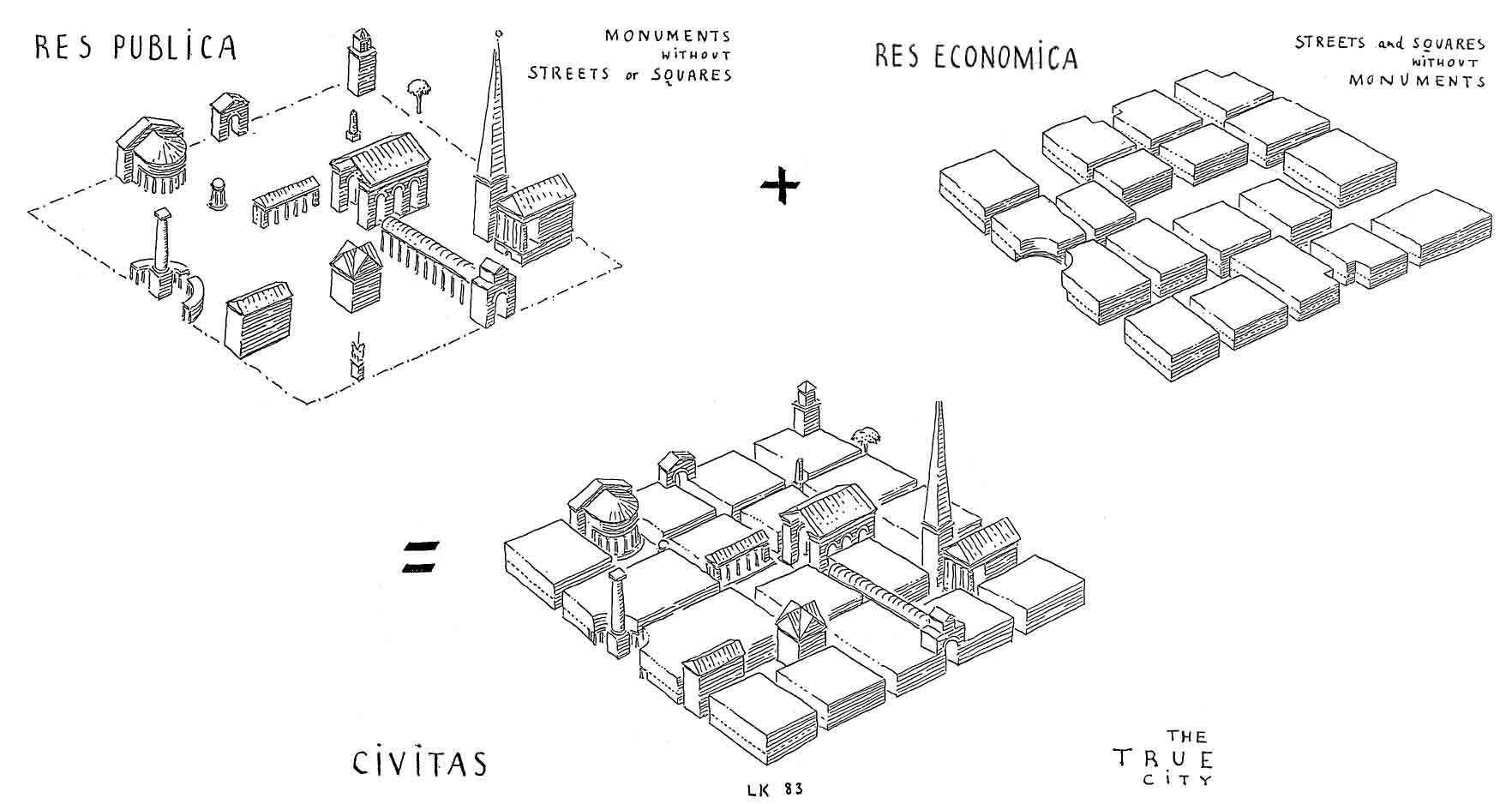

This drawing by the late, great Leon Krier further distinguishes between public buildings and private buildings. Note that the public realm of streets and squares depicted by Krier is not possible without the three points highlighted above from the Charter.

The public realm is publicly owned, but the buildings that form the walls of the rooms are mostly privately owned. Because of that, Andrew Burleson calls the term “misleading” in his substack publication, the Post-Suburban Future, “because the most critical part of the ‘public realm’ is not public property, rather it’s the way that each building attaches itself to the street.”

Burleson highlights a contradiction, or perhaps an irony, pertaining to the public realm. If the public realm is public, and it feels like a series of “outdoor rooms,” then the walls of those rooms are largely privately owned. That is true in every great city or town. Much of the character of these places is defined by the architecture of the buildings.

Burleson calls building frontages, or facades, the “interfaces.” “We should regulate the interface because that’s what gives us the positive externality. Understand that this is not about architectural style or level of luxury or expense; I find that the humblest buildings often have the best interfaces. Rather it’s the functional aspects of how a building attaches to the street — where are the entrances, how many are there, how much space is there between entrances, what’s happening on the ground floor — that either contribute to a safe and convivial environment, or take away from it.”

Burleson argues that the interface is the most important focus in creating a good city. I would take issue with that. As the Charter makes clear, the design of streets and public spaces is just as important as the design of frontages.

The public realm must be walkable, connected, and human-scaled. Without that, good frontages only have limited utility. New urbanists advocate for regulating the building interface through a form-based code. However, we also need good streets and public spaces, and that is often the responsibility of public works and transportation departments.

The public realm is a dance between buildings and the spaces between them. The dance steps involve more than just the interface, although the interface is key. The city also needs a good framework of interconnected streets and public spaces. If I had to choose, I would give those priority over good building frontages, because the streets are harder to change than the buildings.

Well-designed streets are another “positive externality,” to use Burleson’s phrase. Streets are where the public realm often breaks down. And yet cities usually have direct control over streets.

The public realm is an ideal that requires never-ending improvement. But one thing is certain: You can’t make a great city, without a great public realm.

For more reading on the public realm, read this Great Ideas article.