How art launched New Urbanism, changing planning history

When the New Urbanism began thirty-some years ago, its practitioners faced a steep uphill battle. Zoning codes across the US made it illegal to build walkable places (more so than today). The real estate finance system was heavily weighted towards single-use, suburban development. Traffic engineers designed roads that were uniformly hostile to walking (even more so than today). Land-use specialists of all kinds were more comfortable with single-use, automobile-oriented models.

But the nascent movement also had a few things going for it. Its ideas seemed radical at the time, but they were based on centuries of city and town building (Someone said New Urbanism is the radical idea that people can get out of their cars and enjoy a beautiful place). Most people had, buried in their hearts, a memory and love of main streets and traditional downtowns—even if they rarely visited these places. They still went to walkable communities on vacation for fun and a respite from modern sprawl.

Perhaps most importantly, the quality of the plans and graphics for conventional development was lousy. They were dry, technical, and often ugly, presented in planning meetings by land-use lawyers who knew little about design. After all, a conventional developer only needed to count the right number of units, floor-area ratios, and parking spaces, provide a few trees and a nice, wide access road, and approvals were automatic. Sprawl was a well-oiled machine.

Architectural visualizations were not much better. “Cold abstraction and esoterica in both architecture and architectural illustration had been the order of the day for decades, weakening the ability of ordinary citizens to fathom what was being proposed, as the profession withdrew from the public,” notes leading new urbanist designer Victor Dover, in a foreword to The Art of the New Urbanism: Volume 1 (1980-2010), published by Wiley in June.

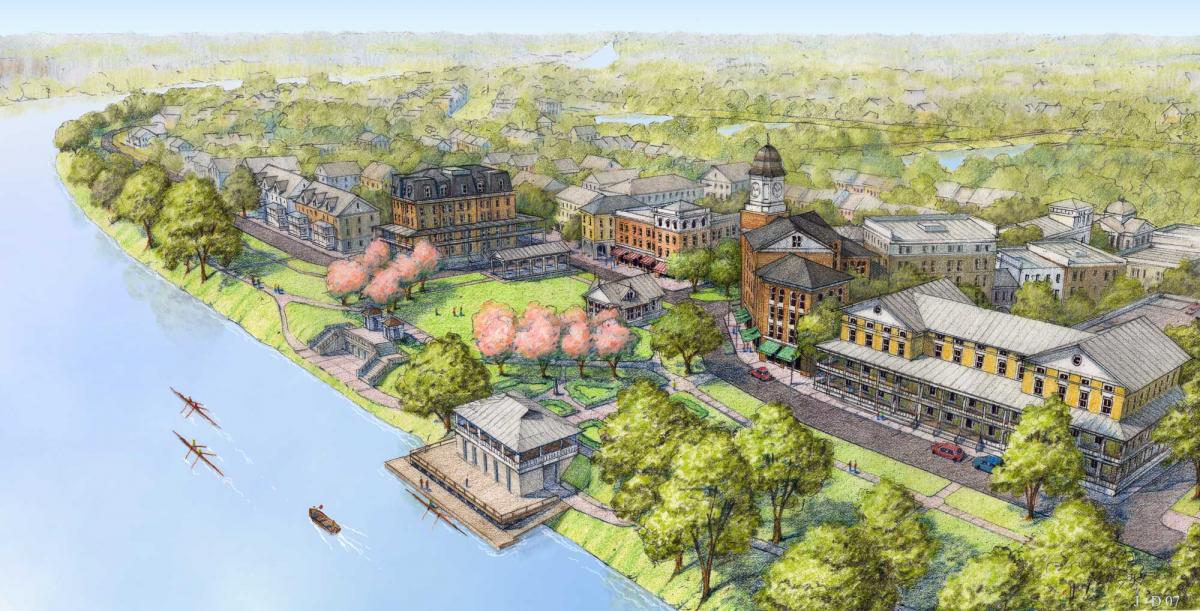

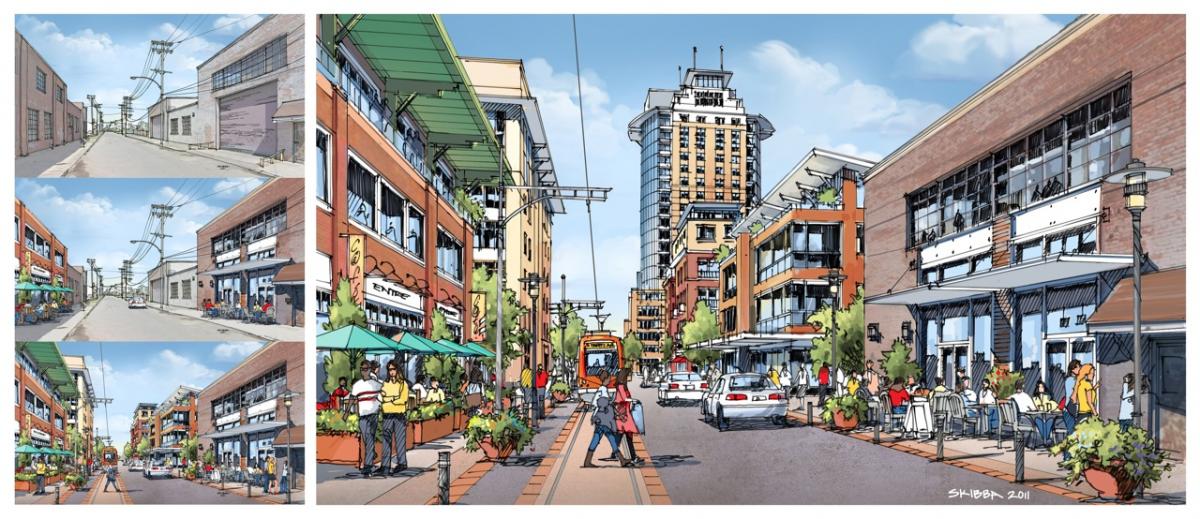

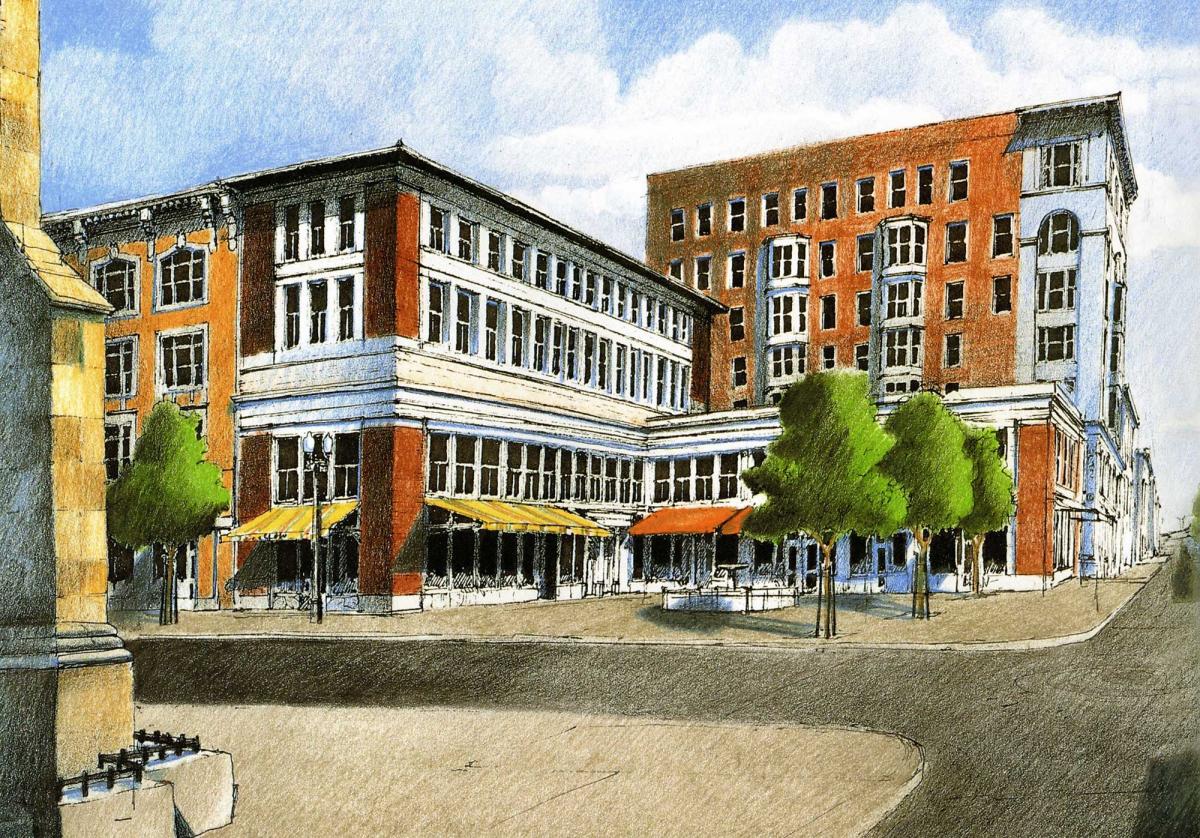

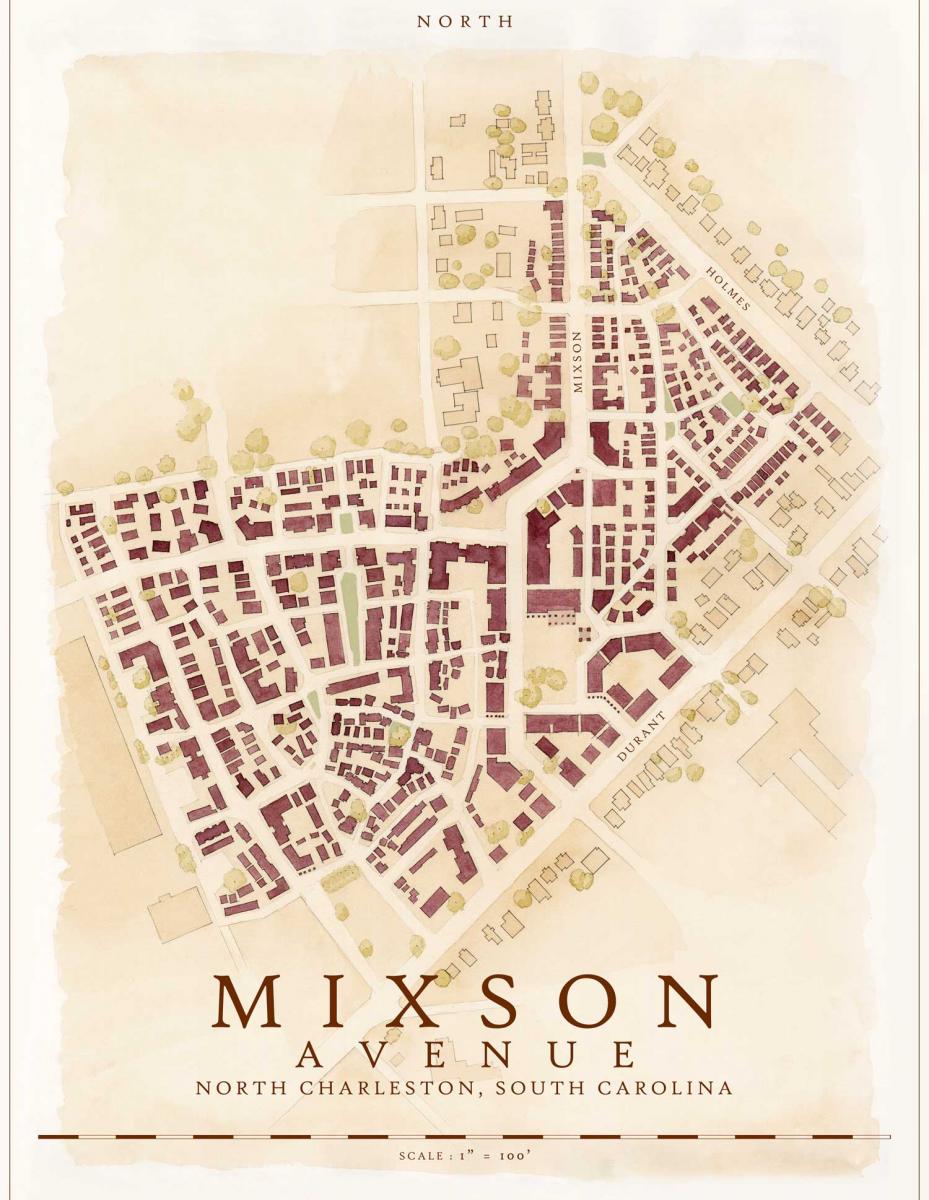

In that breach, new urbanists found an opening. They set about offering the opposite of conventional development in meaningful ways. Rather than single-use, they proposed mixed-use. Instead of an automobile orientation, the plans showed walkability. And rather than dry, technical plans and renderings, they often presented stunning, colorful, and artistic visions of urban neighborhoods with human-scaled public places.

This artwork has not been given its due, according to The Art of the New Urbanism authors James Dougherty and Charles Bohl.

The art, like the new urban design charrette, was innovative in US planning and development in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. This book highlights what has been forgotten—how art played a key role in the most important urban design and planning movement of the last four decades. New urbanists had to rediscover the artistry and craft of mixed-use urban design, and the group, largely composed of trained architects, drew inspiration from American city and town planning of the early 20th Century. Explain the authors:

“Since 1980, the New Urbanism movement has been transforming the dialogue about community planning, real estate development, and architecture. Out of necessity, New Urbanists have revived and advanced techniques of visual communication that enable developers, professionals, elected officials and citizens from all walks of life to engage with the design of their streets, neighborhoods, and regions. Created as means to an end, many of these visualizations are nevertheless compelling works of fine art in their own right.”

Art plays an underappreciated role in the urban design process. The artists help community members to envision how places could be created or changed, enabling residents to participate in the planning process. “People tend to think whatever is already built in their neighborhood is either permanently stuck as is, or that developers and city officials are threatening to make it a lot less livable and attractive,” says Dover. “They will hold on to those assumptions unless designers show them otherwise.”

Renderers are not just there to make things look pretty for the audience of citizens, stakeholders, and public officials. Rather, they are part of the planning team, exploring and presenting ideas, through skilled use of perspective, in three dimensions. Many ideas for parks, how public space could be used, or architectural expression, were born in the imagination of the artist. “Andrés Duany has said that “In a charrette, there is always a hypothesis,” says Dover. That hypothesis might change as the work goes on, but from the beginning there is something to put on the wall for everyone to see and interact with.

Artists test ideas by drawing them. Concepts may sound good or bad when spoken, but the flaws, if any, are revealed in the drawings. “We also draw versions that are suggested along the way that, first hearing them, might sound like bad practice,” Dover quotes Duany; “later, through the process of comparing ideas and getting feedback, the versions that are unworkable or lacking tend to slide down the wall.” In other words, ideas from the public are not simply dismissed, but drawn. Some ideas end up being good ones. But if not, at least the citizens know they were heard.

At the same time, the renderings and plans were designed to sell. One of the best new urbanist artists, Charles Barrett, who died an untimely death in 1996, “was chided that he was producing the equivalent of propaganda posters,” according to Duany, quoted by Bohl. “He was of course uncomfortable with architecture [being used] in this role, but the effect was nevertheless delivered, as everything he drew was admired, even by the least sophisticated.” Beautiful images resonate with people on a subconscious level. People fall in love with places and communities, and some become committed to urbanism, only later working out the rational arguments.

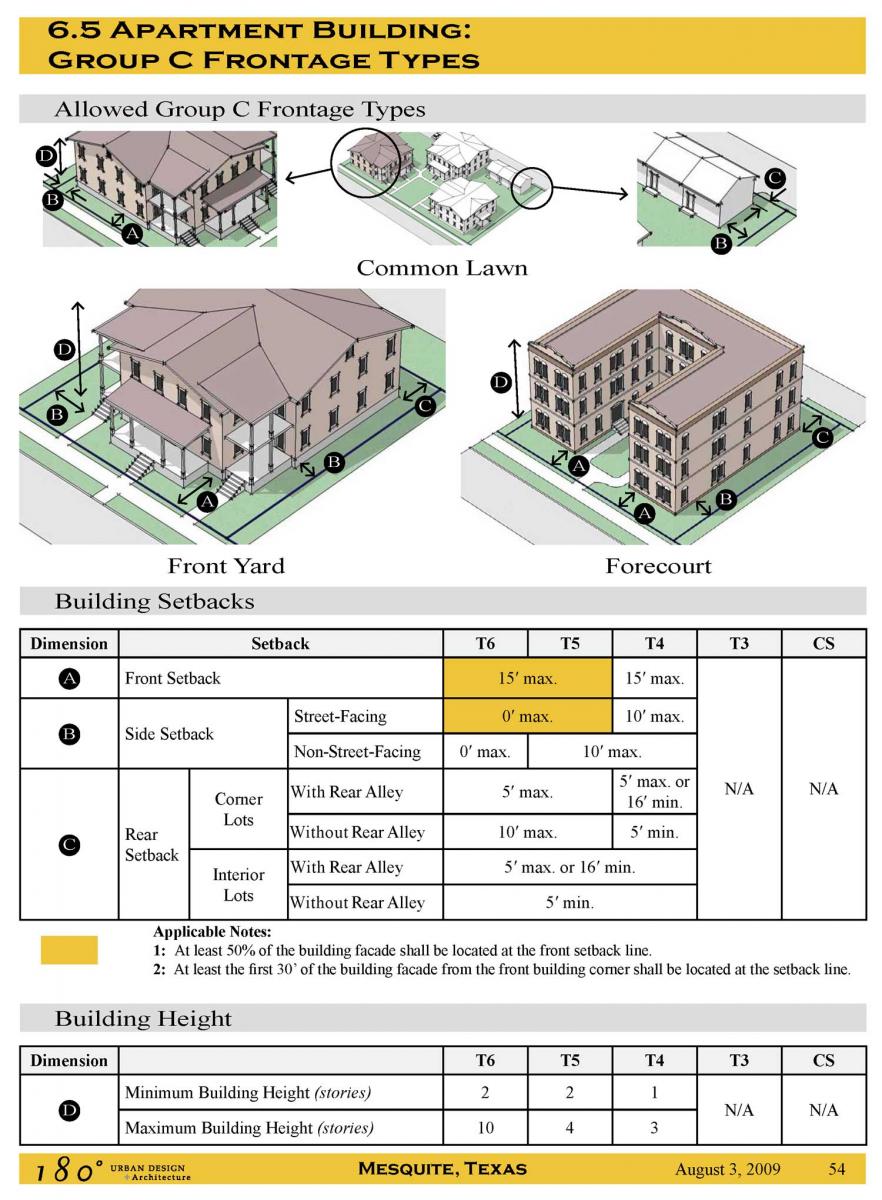

Also at that time, “city planning had also become buried in cryptic, confusing regulations and policies written in longform legalese,” Dover explains. The new urbanists used their drawing skills to produce graphical codes that were simpler and easier for people to understand.

While the drawings may or may not be art, codes like the proposed Mesquite, Texas, TND ordinance stand apart from typical land-use laws to “make zoning more urban, accessible, and user-friendly.” “The codes were concise and artistically illustrated, making them unimaginably easier to understand than the voluminous, legalistic land use regulations we were accustomed to,” Bohl writes.

The book contains 260 renderings, plans, and photos by over 100 practitioners, representing the best of art and artistry of the New Urbanism during its first three formative decades, notes co-author Dougherty, principal of Dover, Kohl & Partners. The book grew out of an art exhibit at CNU 20 in West Palm Beach, Florida, in 2012. The illustrations and plans were done when hand-drawing skills were the norm, prior to recent advancements in computer graphics. Gathered together in print for the first time, the overall impact is impressive.

“I can’t help but think that we were part of a Golden Age of illustration of urban design that was happening at the time, where the culture, the hand-drawing, and reaching out to people and showing them through drawing what their future could be like was really at a full zenith,” comments David Csont of UDA, one of the artists whose work is featured, in a promotional video for the book.

As the title indicates, the book covers early new urbanist art, and the authors are already soliciting work from the last 15 years.“Vivid visualization made sense for New Urbanism because the movement was (and is) results oriented, and its adherents have tended to eschew abstraction and sterility,” Dover says. Often, art becomes a symbol of community, or public space, or a vision that helps to carry a project through to completion.

While this is true today, this art grew out of conditions of a movement that was challenging the status quo in every way. As New Urbanism has become more familiar to the public and codes reform makes it easier to build, do planners need to expend such resources on visuals? New urbanists are still producing good art, but that art is changing. More of that work is being done through computer-generated illustration. It will be interesting to see what the next volume reveals.

For now, Volume 1 is an inspiration. Planners should have this book with them, on charrette and in the office, for examples of the best new urbanist planning artwork. Just as other books may show street design options, building types, architectural styles, and public spaces, The Art of the New Urbanism will point the way on images. What kinds of illustrations will get the job done? The answers are in these pages.

The Art of the New Urbanism is a beautiful book, and it is one that tells a story. It is the history of the New Urbanism through the various media of visual illustration. That makes a compelling narative, one that is inseparable from the history of the movement as a whole. The Art of the New Urbanism makes an important contribution to understanding urban planning over the last half century and is an essential addition to the urbanist’s bookshelf.