CNU releases Freeways Without Futures 2025

CNU just released its ninth biennial Freeways Without Futures report. Since 2008, CNU has presented a list of highways through cities that we and others think would be better unbuilt. The report has spearheaded our efforts to draw attention to the damage caused by in-city freeways and the alternative solutions.

“Since its founding in 1993, the Congress for the New Urbanism has been a fierce champion for the removal of the urban freeways that divide communities, jeopardize health, damage local economies, and endanger people’s lives in every city across this country,” says CNU President Mallory Baches.

As is the case every year, the list is selected by a jury of experts. Below are descriptions of projects and removal campaigns, with commentary. Read the full report here.

Interstate 35, Austin, Texas

In 1962, the twelve-lane I-35 replaced what used to be East Avenue, a four-lane boulevard with a large grassy median that served as a public park. Ever since, that huge highway has created a physical barrier between East and West Austin. Despite significant opposition, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) has broken ground on a project to expand 28 miles of the highway to as many as 22 lanes. Like a demented game of Texas Hold ‘Em, TxDOT is doubling down on a bad planning idea. The level of pollution and negative impact that 22 lanes of high-speed traffic on city neighborhoods is hard to imagine.

Despite the state seemingly moving ahead with this project, two popular local campaigns are fighting on. Reconnect Austin, founded in 2012, proposes sinking and covering I-35 with a boulevard while Rethink35, founded in 2020, advocates for rerouting I-35 around town and replacing the current highway with a boulevard. However, TxDOT refused to thoroughly study either proposal. Both campaigns have had considerable success in changing local attitudes around I-35 and urban highways in general.

NY State Routes 33 and 198, Buffalo, New York

When New York State built the Kensington Expressway (Route 33) in Buffalo, New York, they traded the equivalent of a 50-dollar gold piece for a nickel. The gold was the Humboldt Boulevard, a tree-lined thoroughfare with a park at the center designed by Olmsted. That urban corridor was the center of gravity for many neighborhoods, drawing people in with its beauty and utility. The expressway, which no one would call beautiful, has divided the city for six decades. It had helped people get from the suburbs to downtown, but it also encouraged people to move to the suburbs and induced its own demand.

The NY State Route 198 Scajaquada Expressway similarly cuts primarily through the greenery of North Buffalo's majestic Delaware Park, but also pollutes one of Buffalo’s major urban freshwater ways, the Scajaquada Creek.

In Spring 2022, the city and state bought into the 're-envisioning' of these problematic routes with federal Reconnecting Communities financing and buy-in from the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) to move forward with a cap-and-tunnel approach. Unfortunately, community sentiment is at odds with that idea.

Instead, there is widespread support among a community network of more than 100 member organizations, environmental groups, the respected regional think tank Partnership For The Public Good, the Scajaquada Corridor Coalition, and East Side residents for the complete removal of the Kensington and Scajaquada expressways. This move would bring back the beauty of the boulevard and parkways that existed before.

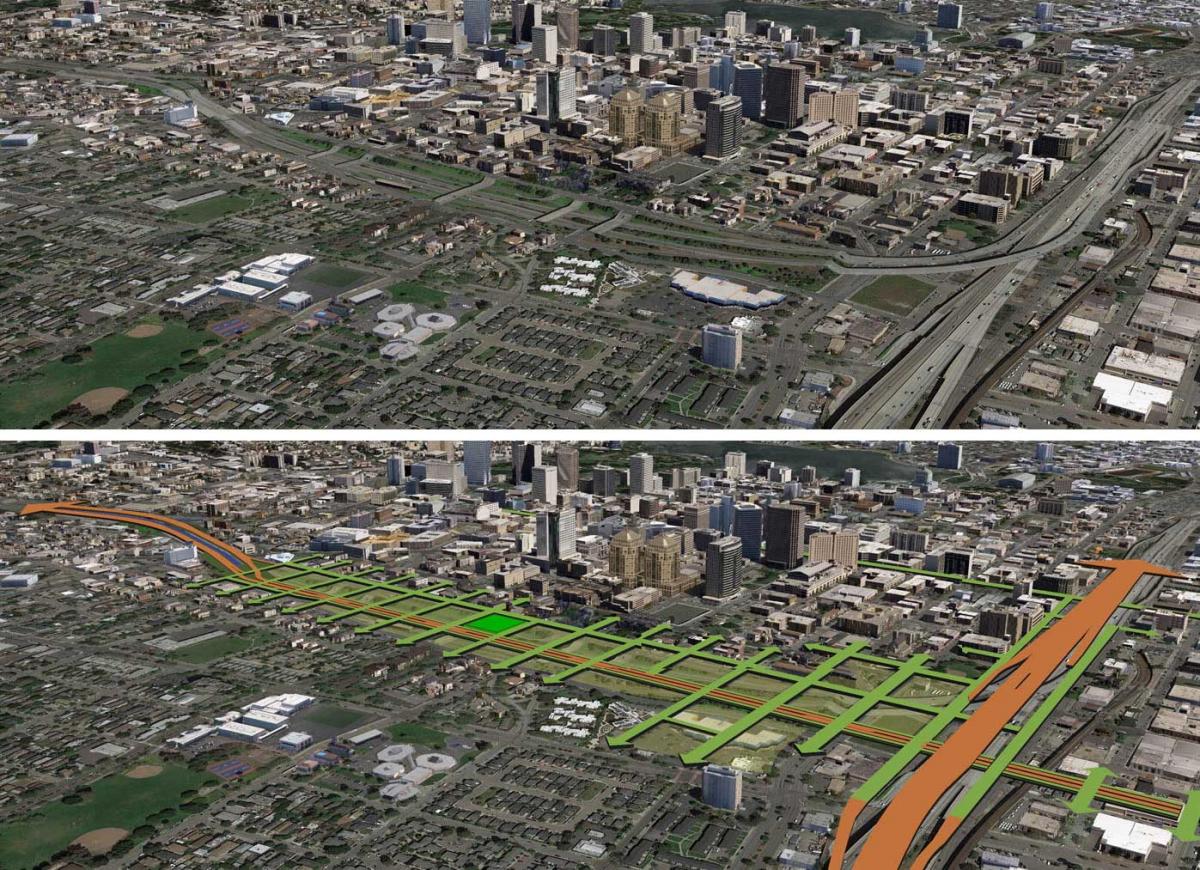

Interstate 980, Oakland, California

This section of in-city freeway has “only” five lanes, yet it seems to have been designed to be as wide as possible. The system of on-and-off ramps and service roads gives I-980 a 560-foot cross-section—about the width of two city blocks. The freeway’s construction in the 1970s displaced thousands of residents, disrupted longstanding community networks, and imposed a physical barrier that separated West Oakland from the economic and social opportunities in the rest of the city. Nice job, long-ago engineering team.

Vision 980, underway now, is imagining a new community vision, including housing preference, economic development, workforce initiatives, tax increment financing, cultural preservation, and anti-speculation policies.

Interstate 45 expansion, Houston, Texas

Before I-45 was built in the 1950s and 1960s, the corridor served as a rail connection between Houston and Galveston on the coast. Homes and businesses were demolished to make way for the new highway, leading to extensive displacement. The concrete infrastructure has worsened stormwater runoff, contributing to flooding issues that still plague these areas. The adage “when you are in a hole, stop digging,” comes to mind—but we are talking about Texas, where the last seven decades point to only one very costly response … more pavement.

The expansion would directly contribute to the loss of historic bayous, destroy flood-absorbing land, and increase concrete sprawl. These harms fall hardest on Houston’s Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. A grassroots campaign, STOP TxDOT I-45, is fighting the North Houston Highway Improvement Project (NHHIP), arguing that the $13 billion allocated for NHHIP could instead be redirected toward multimodal transportation projects. This could include enhancements to public transit systems, expanded bike lanes, and improved pedestrian pathways, making it easier and safer for residents to travel without relying on cars.

Interstate 175, Saint Petersburg, Florida

The construction of I-175 in the 1970s displaced over 4,000 residents, primarily from Black neighborhoods, and severed connections between downtown and the Southside. Built to provide access to downtown and its medical facilities, the highway now operates at an unimpressive 40 percent capacity. Crashes on the feeder roads to the freeway account for disproportionate injury and death, but at least access to emergency care is good.

The city completed a mobility study of its downtown street network and labeled the reconfiguration of I-175 as a priority one project. From there, the MPO Forward Pinellas recommended a feasibility study, and FDOT has funded an $800,000 feasibility study of different options, including a viaduct, a cap, a boulevard, or leaving the highway in place. The campaign Reimagine 175 is advocating for the Boulevard option as it provides the most benefits for St. Petersburg communities.

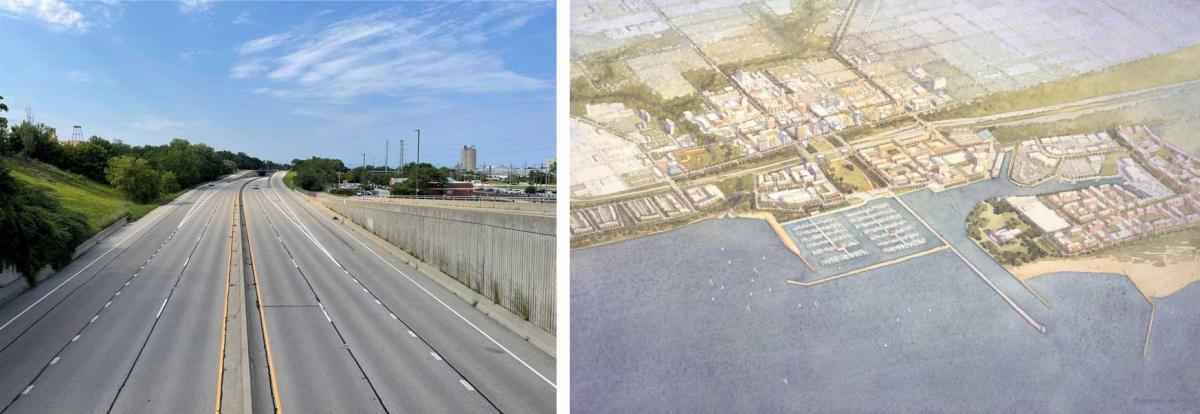

IL 137/Amstutz Expressway, Bobby Thompson Expressway, Waukegan and North Chicago, Illinois

Talk about miscalculations: The IL 137/Amstutz Expressway was built in the 1970s-1990s to connect the industries of Waukegan and North Chicago’s lakefronts to I-94 and north to Wisconsin without burdening their downtowns with heavy industrial traffic. But planned extensions to the highway were never built, and the industry disappeared. What remains is an overbuilt road to nowhere that diverts visitors to the cities’ downtowns and cuts off neighborhoods from the major amenity, Lake Michigan.

Expressway removal would immediately benefit residents with improved connections to the lakefront, Waukegan Harbor and Marina, Waukegan Metra Station, and Waukegan Municipal Beach. The improved grid connections would restore the neighborhood fabric and give residents of Waukegan easier access to jobs, healthcare, local businesses, and recreation spaces. Lower speeds along the corridor will reduce exhaust and noise pollution, improving the health of an environmental justice community. Development can potentially boost the tax base to support municipal services and prevent a higher tax levy.

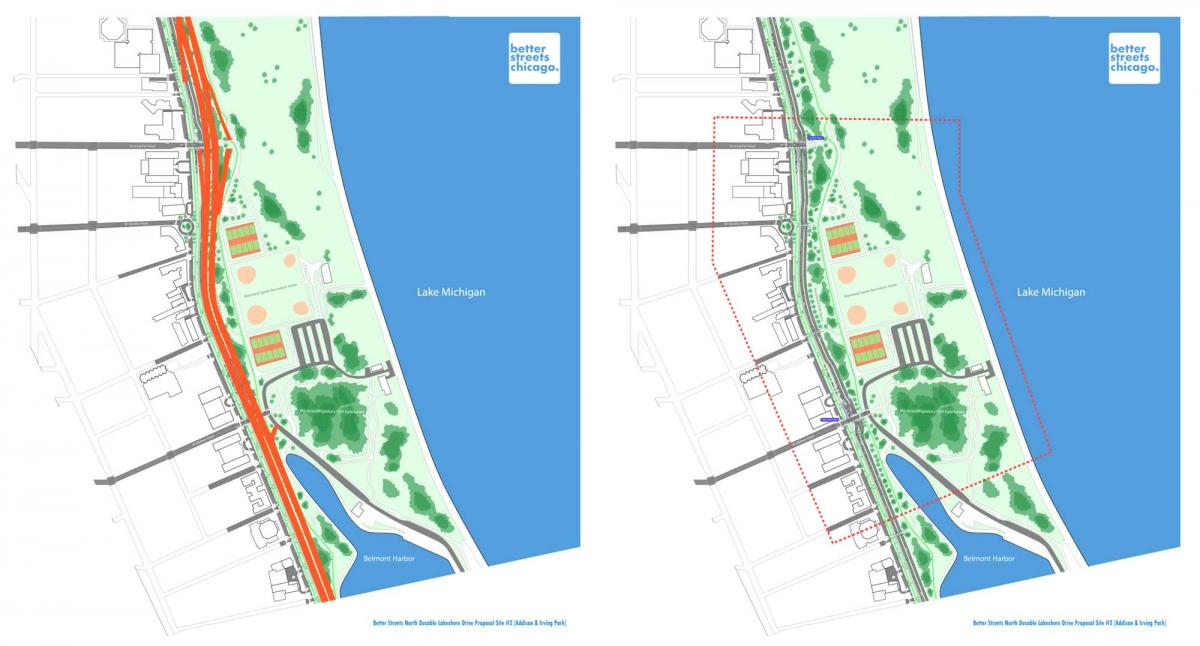

DuSable Lake Shore Drive, (US-41), Chicago, Illinois

The DuSable Lake Shore Drive (DLSD) is an eight-lane highway that runs 15.8 miles from Hollywood Avenue in the Edgewater neighborhood on Chicago’s North Side to 63rd Street in the Jackson Park neighborhood on the South Side. Initially, the road was a true “drive” (not a highway) along the natural lakefront corridor, intended for leisure drives through the (then) new lakefront parks, in a right-of-way much narrower than exists today.

The Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) is leading the Redefine the Drive planning project, which proposes to enlarge DLSD and rebuild it to Interstate-grade expressway standards. In Chicago’s nearby Graceland Cemetery, the great architect and planner Daniel Burnham is rolling over.

But Better Streets Chicago is presenting an alternative vision for transforming DLSD into a boulevard to reduce travel speeds, increase safety, encourage mode shift, prioritize transit, and improve conditions for pedestrians and cyclists. There is consensus that the corridor should be rebuilt accordingly.

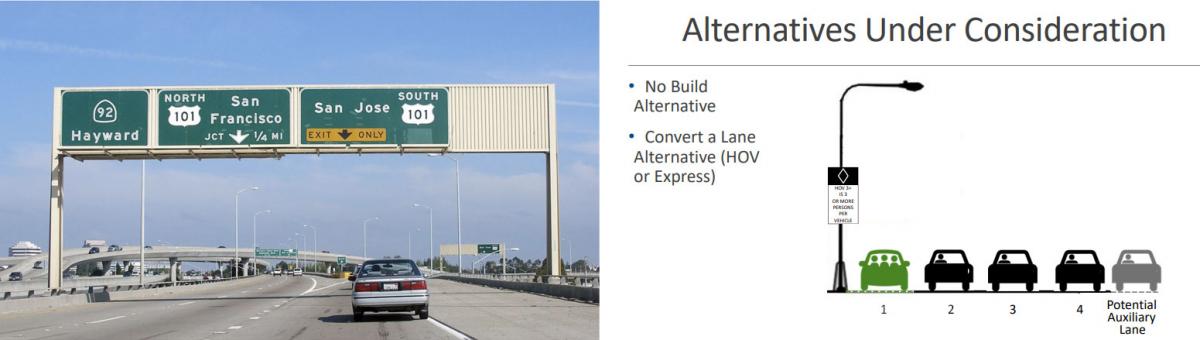

US-101, San Mateo County, California

US-101 in its current form was constructed in 1964 and divides the densest parts of San Mateo County. Apparently, it’s not enough that the corridor, which has a disproportionate population of low-income people of color, is impacted by pollution from industry and the airport, in addition to the highway.

Since the 2010s, Caltrans, the San Mateo County Transportation Authority, and the City/County Association of Governments have embarked on a journey to widen US-101 between Santa Clara County and San Francisco County. Phase 3 of this highway widening proposes around 30 miles of Express Lanes and auxiliary lanes, undermining investments in the parallel Caltrain commuter rail service.

The local campaign, Stop 101 Widening, has gotten nearly 1,000 petition signatures and is mobilizing community members in Downtown South San Francisco to understand and organize on environmental justice issues in their community.

US-35, Dayton, Ohio

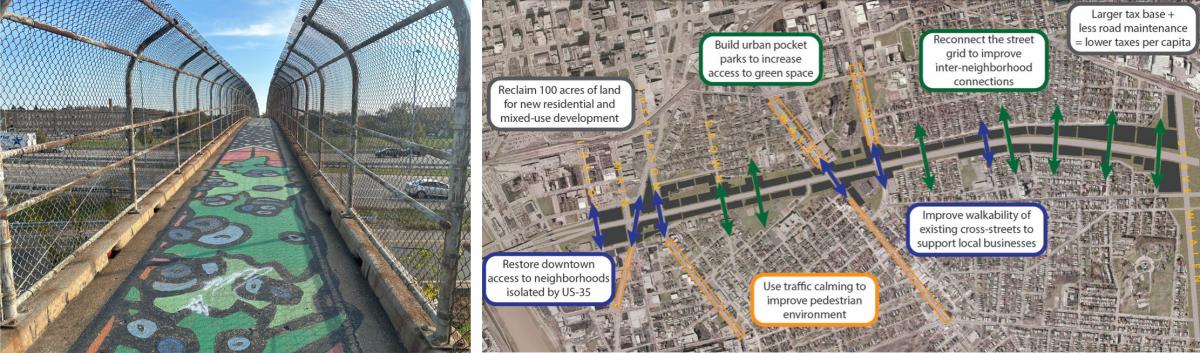

Planned and built in the 1960s, US-35 tore through numerous local communities and reinforced segregation within the corridor. As a result, these once-thriving communities were severely harmed as hundreds of homes and businesses were destroyed to construct the highway. Many generations later, abutting neighborhoods have begun to recover slowly, but the highway has impeded development. If real estate is location, highway-adjacent is not a neighborhood amenity.

A local campaign, Dayton Freeway Removal, is actively building support for removal, and city officials have applied for federal Reconnecting Communities funding to research alternative designs. The alternative design proposes converting the 240-foot-wide highway corridor into a 4-lane boulevard with shared-use paths on both sides, reducing the roadway footprint to approximately 100 feet. The remaining land, including land presently occupied by interchanges, will be repurposed for housing, parks, and other developments.

The jury for the 2025 includes Karina Yonekawa-Blest, president of Fonde Civic Club in Houston, Texas; Wes Marshall, professor in civil engineer at UC-Denver; Regan Patterson, professor in civil and environmental engineering at UCLA; Gonzalo Contreras of Santaoyála Consultores y Asociados; David Bragdon, principal with Hudson Skykomish; Luis “Sito” Negron, senior policy advisor with El Paso County; Mark L. Stout, principal, Mark L. Stout Consulting.