New Urbanism is inclusive urbanism

In the fall of 2023, a group of just over 30 academics and professionals in various sectors of the urban design and planning field came together in Washington, DC, to share perspectives and engage in discussions to begin improving new urbanists’ understanding of what it means to make cities, towns, and neighborhoods livable for all people—regardless of race, gender, or ability.

To be clear, inclusive urbanism is not a novel idea within the sphere of new urbanist practice and is certainly not a ‘new initiative’ for which CNU is developing programming. In fact, the CNU Board of Directors formally adopted its Statement on Inclusion over 5 years ago in 2018. However, CNU recognizes that to provide the tools and the educational resources to help its members incorporate inclusivity into practice, convening practitioners and those with lived experiences to share their knowledge and challenges is critical. With the guidance of a steering committee, CNU planned a series of convenings to define “inclusive urbanism” and determine how new urbanists could adjust their practice based on improved understandings, beginning with A Dialogue on the Gendered Urban Experience.

Historically, men have predominantly been responsible for constructing, designing, and planning cities, thereby establishing their perspective as the dominant influence on how urban areas and public spaces operate. Consequently, urban design and infrastructure frequently neglect to address the specific needs, roles, and responsibilities of women. By failing to account for the needs of half of the world’s population in urban design, the built environment has been a key force in perpetuating gender inequities.

Today, cities around the world are still planned, built, and managed based on traditional gender roles where men are the primary wage earners and women make up the majority of those engaged in mostly unpaid care work. While the societal roles in the US have evolved to include dual-income households and a lean toward more egalitarian politics of care, the design paradigm for American towns, cities, and suburbs has not kept up.

The first convening of the Inclusive Urbanism series, A Dialogue on the Gendered Urban Experience, was held in collaboration with the National Building Museum in November to explore gender mainstreaming as a strategy for inclusive urban planning. Through this partnership, CNU had the opportunity to work with Delores Hayden, recipient of the Museum’s 2022 Vincent Scully Prize recognizing excellence in practice, scholarship, or criticism in architecture, historic preservation, and urban design. As professor emerita of architecture, urbanism and American studies at Yale University, Professor Hayden has been asking “what a non-sexist city would look like” for more than 35 years. Her views on stereotypes of gender and race embedded in the American built environment was an inspiring backdrop to the discussions that would flow throughout the day.

Moderated by CNU president Mallory Baches, three presentations would serve as prompts for further dialogue on the gendered urban experience: Gender Assumptions in Planning and Transportation by Ines Sanchez de Madariaga; Fair Shared Cities by Eva Kail; and Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman would show participants images of what a feminist-led Business Improvement District looks like.

Gender assumptions in planning and transportation

Ines Sanchez-Madriaga, Professor of Urban Planning at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and UNESCO Chair on Gender, shared her experience of urban planning policy in Madrid, Spain, where urban planning documents are legislative instruments that must include gender impact assessments. Not only are gender considerations expected to be incorporated into the design process but, also, when awarding contracts gender is a criteria in the expertise of the design team.

Sanchez-Madriaga compared the underlying assumptions of modern planning with gender assumptions in planning and transportation, and advocates for a shift towards considering care as a fundamental concept in urban and transportation planning. Traditional planning assumptions often overlook the unpaid care work performed by individuals, particularly women, for children, the elderly, and the infirm. Furthermore, planning tends to focus on the needs of those in paid employment, and housing is seen as a place of leisure instead of its care implications.

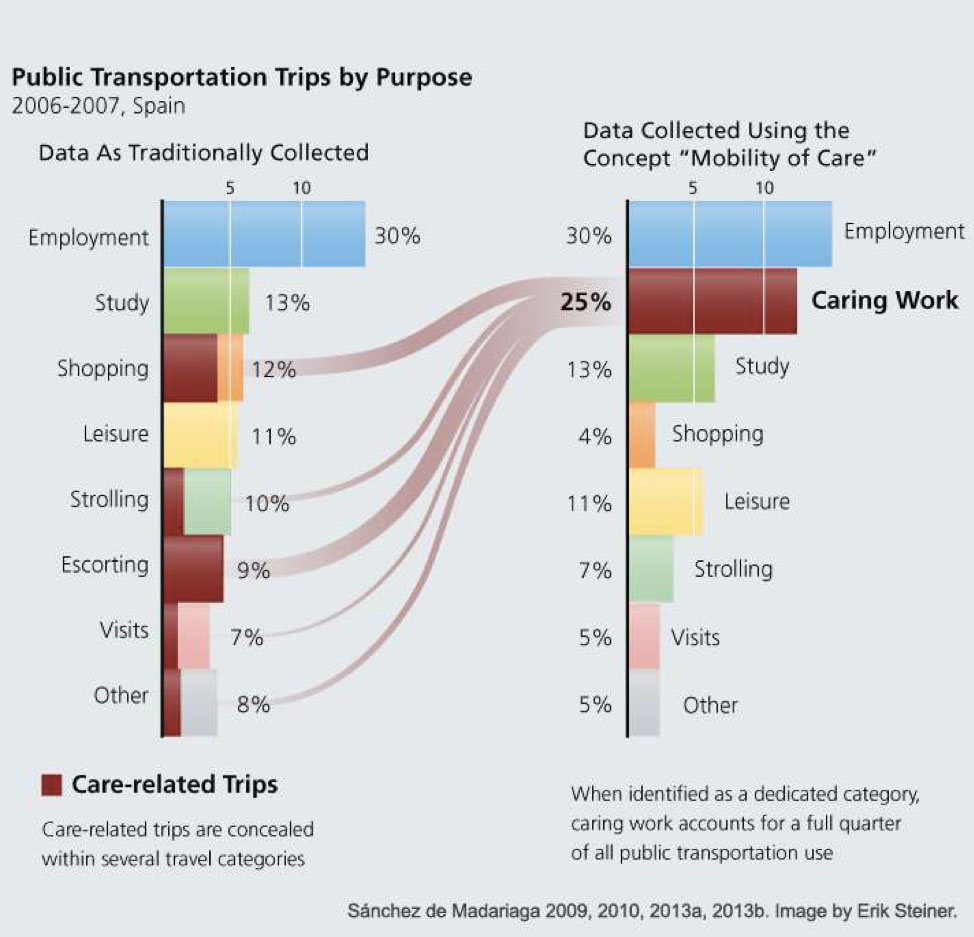

Research conducted by Sanchez-Madriaga led to the concept of "The Mobility of Care" to serve as an overarching framework that aims to quantify and highlight the trips made by adults for caregiving responsibilities and household maintenance. She criticized most surveys for their inability to precisely quantify these journeys due to gender biases and oversights. Rather, her hypothesis suggests that a significant portion of trips typically categorized as shopping, visits, or even driving people from one destination to another (escorting) should actually be considered care trips, potentially comprising between one-third and two-thirds of such trips. To ignore the design implications of one-third to two-thirds of trip purposes fails to take into consideration the true need for a transportation plan.

Sanchez-Madriaga noted that the mobility of care encompasses various aspects of new urban design and planning paradigms to support a gender-egalitarian society. This includes creating the 15-minute city, mixed-use neighborhoods, diverse housing options, accessible services, quality transit systems, safe public spaces, and preserving land, natural resources, and cultural sites.

Fair shared cities: Vienna’s gender planning approach

Vienna-based urban planner Eva Kail has popularized gender mainstreaming in the design of public spaces, transportation, and housing since the early 1990s. After over 30 years of overseeing gender-sensitive urban planning projects in Europe, she is urging U.S. design practitioners and policy makers to follow suit.

Design approaches and policy decisions are often biased in urban planning, favoring male, white, and middle-class perspectives. However, rather than focusing solely on the needs of women, Kail proposes moving beyond biological categories. Viewing the city as a social system instead of a technical one makes it easier to consider social roles, life phases, and cultural backgrounds as the basis for more inclusive and equitable urban planning. Considering diverse gender perspectives promotes fairness and accessibility for all, not just women.

The City of Vienna, where gender planning initiatives are branded as efforts toward a "Fair Shared City" to underscore the focus on equality, is the owner and publisher of Gender Mainstreaming in Urban Planning and Urban Development. The manual outlines gender mainstreaming as a comprehensive planning strategy and includes design guidelines and policy approaches. Kail recommends that practitioners implement a "Fairness Check" to proposed designs to systematically address the needs of various user groups, and that gender experts are included in competition review panels. Cities can build capacity by equipping planning administrations through gender inclusive design training and with manuals such as the World Bank’s Handbook for Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and Design.

Kail reviewed highlights of a successful urban development project, the Lake-City Aspern (Aspern Seestadt). The site of a former airport, the city-within-a-city is roughly 240 hectares (nearly 600 acres), and has set a population goal of about 25,000 people of diverse incomes, as well as 20,000 workplaces, expected to be completed by 2028. Lake-City Aspern has very few parking garages and its design prioritizes walkable neighborhoods and mixed-use shopping and business districts. Simple visualization techniques like renaming streets with female names and depicting fathers holding babies on 50 percent of public transit signage aim to bridge cultural gender disparities.

A key indicator often used in Europe to measure safety and accessibility of public spaces is the age at which children can move about safely and easily on their own. This means less work for caretakers, giving them peace of mind. Kail also notes that when kids can move through public spaces freely, it leads to more confident children. The design of Elinor Ostrom Park was carefully considered. Framed by an existing elevated rail, the park is not only easily accessible by public transit, but the constant ‘eyes on the street’ by passengers of the raised transit line made park visitors feel safe.

Kail addressed common reservations and fears planning administrations may have about improving capacity and awareness of gender equity projects that, while reasonable, shouldn’t deter or discourage practitioners. Additional costs and workload may both be high at the start of any new project where design processes and programming are being conducted differently, and should eventually decrease as capacity builds. A shift in the focus of how investments are allocated can also help keep costs more manageable. Anticipated negative reactions or skepticism usually come from within the “professional bubble.” Kail has always found wide support from communities.

Women-led cities

Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman is an urban anthropologist who has served in various capacities within academia, nonprofits, advocacy, research and, most recently, working for the City of Philadelphia. She has made it her life’s mission to observe interactions between people and the built environmentand ask the hard question: what would a women-led city look like? After receiving a grant from the Knight Foundation, Johnston-Zimmerman co-founded the Women Led Cities initiative to address the disparity in cities that affects the way women and girls experience, navigate, and thrive in urban settings. Through her work, she has summarized that a women-led city would look a lot like a recent photograph she had taken of South Street in Philadelphia. Normally a traffic-clogged one-way street along a busy retail and restaurant district, her photo shows it’s closed for a street fair with only parked food trucks where cars would be along its sides, and people walking and playing on the street enjoying a nice day in the city. “It comes down to actually the feeling and the accessibility and the kind of access and agency and ownership of cities that [women] just typically don't have … That person-to-person interaction, ownership over the street, safety for children of all ages, and people of all ages, like this, should not be the exception; this should be the norm. And in some places in the world it is.”

Johnston-Zimmerman acknowledged that while Europe is far ahead of the US in feminist city policy and more inclusive planning and design, practitioners can have an impact locally by starting with smaller neighborhood projects “humanizing the street,” and giving the community a taste of what could be. For example, on South Street, an electrical fire at a popular eatery forced it to close for repair work and the standard construction wall was installed. Instead of having city staff constantly monitor and paint over anything drawn on it, Johnston-Zimmerman saw it as an opportunity to invite the community to treat the barrier as an art wall. She commissioned an artist to kick-off the initiative and even made announcements on social media. Not only did it beautify the immediate area and completely transform the block, the initiative brought the neighborhood and tourists together through art.