Traveling near and far toward low-carbon cities

The conventions of New Urbanism show maps of urban areas dotted with quarter-mile circular pedestrian sheds. Recent thinking expands planning units of urbanism to walking or bicycling sheds of 15 minutes. An emerging multimodal transportation revolution is adding more dimensions that stretch ranges further. Urban planner Peter Calthorpe suggests that “we're moving toward a really complicated wonderful mixed-modality world”1 of local travel by e-bikes and other emerging modes of mobility. This revolution raises questions about how to define the boundaries of sustainable mobility. The existential threat of climate change demands that we clearly demarcate when automobile use is reasonable and when it is senseless.

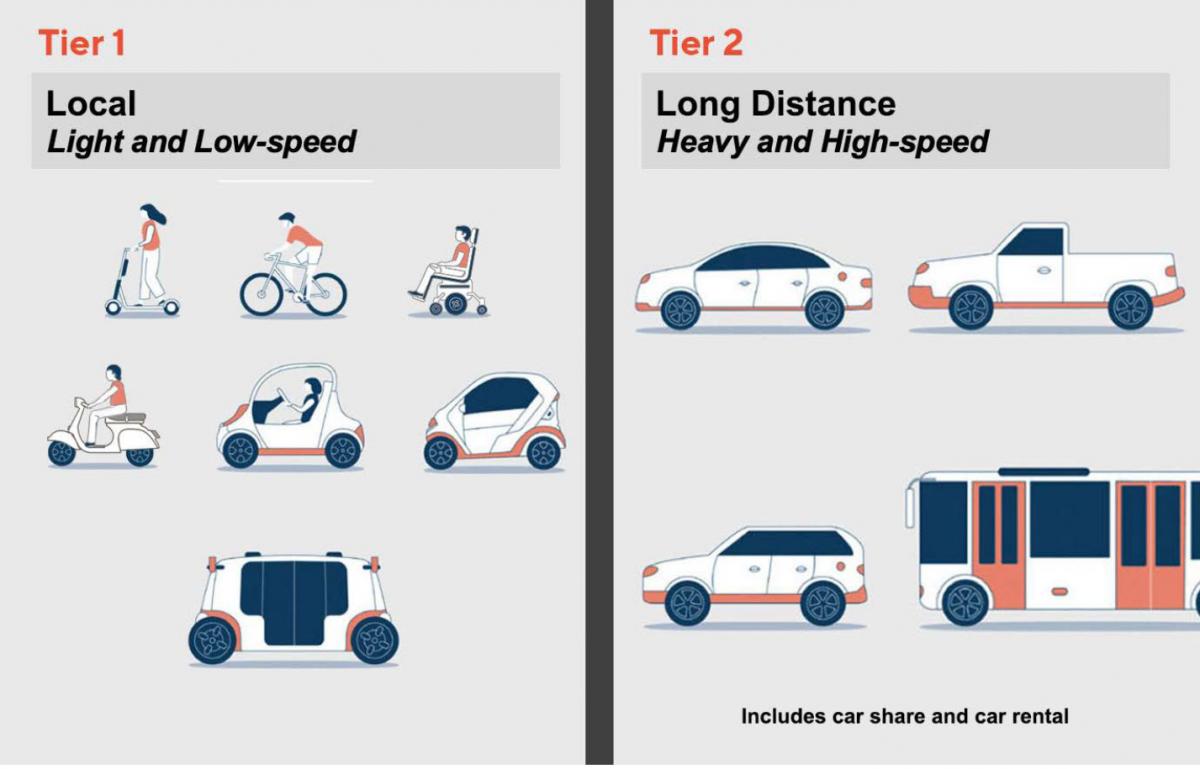

In his book Near to Far, vehicle designer Dan Sturges suggests that we need to distinguish local, low-speed, lightweight vehicle travel, what he calls Tier 1, from long-distance, high-speed, heavy-vehicle travel, what he calls Tier 2. A third, Tier 3, involves going to airports and flying on jet planes2, but for a focus on ground transportation, let’s put Tier 3 aside. Until now, in America, mobility has mostly meant cars—a one-tier system. Vehicles weighing 4,000 to 6,000 pounds are used for all trips, no matter how near and how trivial the cargo demands. If we go to the drug store to buy toothpaste or go to a hair salon to get a haircut, we will get into a vehicle designed to go 75 mph for hundreds of miles. Yet, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, only 2 percent of trips in the United States are over 50 miles.3 Americans are feeling “range anxiety” over the distance electric cars can drive and worrying about available charging infrastructure if they go on a road trip. Yet road trips are not a part of regular experience. Our concern should be how we are traveling locally.

The concept of “two-tier mobility” attempts to impose discipline on America's mobility habits, but in a way that acknowledges the value of full-size cars while being more discerning about their use in daily living. Tier 1 vehicles are bicycles, scooters, mopeds, neighborhood electric vehicles (NEVs), and an emerging class of small, autonomous shuttles transporting 8 to 12 passengers at slow speeds. Over 71 percent of travel in America is within a radius of 8 miles or less. This sweeps out an accessible area of over 200 square miles, depending on geographic constraints. Within this nearby but generous zone, seeking out a freeway for travel doesn't save much time. Some Tier 1 vehicles—e-mopeds and NEVs—can easily handle traveling 8 miles and back. Sixty-two percent of travel is 5 miles or less; 5 miles is easily done by bicycle—at 12-15 mph, that would be 20-25 minutes by e-bike; that 5-mile radius encompasses an area of 78.5 square miles. What is the lion’s share of travel for? A moment’s reflection describes Americans’ destinations: drug store, hair salon, medical appointment, groceries, bank, post office, coffee shop, movie theater, library, dinner with friends, bookstore, etc. What is the common denominator? For most homes, they are not far away.

How should "local" travel be defined when e-bikes push the limits beyond the 15-minute city? Even in a micromobility world, a cellular form for the urban landscape defined by neighborhoods with centers is needed. A quarter-mile walking shed defines a neighborhood where civic and social commitments will naturally occur. Fifteen minutes defines the resource area for quickly satisfying daily living needs. Beyond these ranges, electric micromobility potentially will expand how people define their home turf and beyond, increasing the range of local exploration. Allowing and encouraging people to experience other people's neighborhoods is a necessary part of a just democracy. By contrast, automobiles teleport from one place to another, affording little experience of the urban spaces in between.

Tier 1 vehicles against climate change

Electrified Tier 1 vehicles require a small fraction of lithium than do electrified Tier 2 vehicles. A Tesla Model 3 lithium-ion battery weighs over 1000 pounds.4 (This is Tesla's lightest model.) How will we get enough lithium to put batteries in America's 285 million vehicles—and do it quickly enough to meet climate goals? It can take over 15 years for a lithium mining operation to get up to full production.5 An e-bike lithium-ion battery is about 8 pounds; finding the lithium for Tier 1 travel will not be difficult.

Another benefit of small, lightweight, electric Tier 1 vehicles is that their smaller batteries don't require expensive charging infrastructure; except for electric multi-passenger shuttles, they can be plugged into wall sockets—a light load on the electrical grid. These lighter-weight vehicles also lighten the load on America's streets that are seeing declines in pavement condition index ratings.6

Another benefit of Tier 1 travel is that it is fun—if the built landscape allows it. Bicycles, e-bikes, e-scooters, and even neighborhood electric vehicles connect people in an exhilarating way with the environment they move through. The possibilities for enjoyment of Tier 1 travel raise expectations regarding the quality of the landscape. A new bike lane excites anticipation and curiosity. Tier 2 travel doesn't evoke high expectations for places. A new car lane rarely excites motorists with possibilities for new experiences.

Many historic towns—think colonial in New England—have narrow streets that frustrate bicycle riders' dreams of complete streets with bike lanes; there just isn't enough room for the lanes. In these cases, street sizes are less of an issue than vehicle sizes. Nowadays many personal vehicles are as much as 7 feet wide or more. Most NEVs are under 5 feet. Narrower and more numerous Tier 1 vehicles coupled with slower design and posted speeds would allow the pavement to be more safely shared in these historic towns.

Tier 1 travel in the suburbs

Many new urbanists have expressed skepticism that auto-oriented suburbs can be made sustainable other than by putting photovoltaics on roofs and electric cars in driveways. But the carbon footprints of the suburbs are too big to ignore. Most American suburban development has forgone the street grids of historic town centers for hierarchical street systems with linear commercial arterials where travel movements are constrained to a single path. The tendency of many walkers and bicycle riders to go longer distances than necessary out of the joy of exploration can't compete in these settings compared with the multidirectional wandering possible in gridded town centers. Yet many suburban arterials with their low-density land uses are opportunity corridors for much-needed housing. If redeveloped intelligently, these multimobility/housing avenues could provide rich mixes of useful and satisfying destinations easily accessed via short walks or Tier 1 travel.

Although it may not be possible to make centers along linear suburban corridors as vitally urban as can be found in gridded historic neighborhoods, nevertheless the possibilities shouldn't be underestimated. In many cases, nascent multimobility/housing avenues can be conceived as a complement to downtown revitalization as many of these corridors lead to downtowns. I live in multifamily housing on a suburban avenue with several useful destinations within a short walk. I regularly meet people I know walking on the avenue. As housing gets built on the avenue, more of these serendipitous encounters will occur because the linearity of a corridor with retail and service offerings will focus people's movements. The world is full of attractive avenues and boulevards as proof of concept.

The planning world has typically thought in terms of travel modes: walking, biking, transit, and driving. For planning multimodal/housing avenues, these modes could be conceived as having expected trip distances. For walking and bicycling on these corridors, planning should measure travel in blocks, not miles: walking for two to four blocks, bicycling for five to ten blocks, with taking transit for a half mile to 10 miles. (These numbers are my guesstimate and need to be calibrated to people's physical capabilities.) For long-distance travel not served by transit, car rental or car share should be available as part of a multimodal mobility mix.

Accessing new walkable centers in the suburbs

As Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson documented in their book Retrofitting Suburbia, and Galina Tachieva in her book Sprawl Repair Manual, dead suburban malls and dying office parks can be opportunity sites for walkable development. Many of these potential locations are adjacent to large streets that can be developed as described above, thus enlarging the walkable zone. Yet if these locations are to be more than walkability preserves or regional lifestyle attractions, they need to be accessible from nearby auto-oriented landscapes where people live.

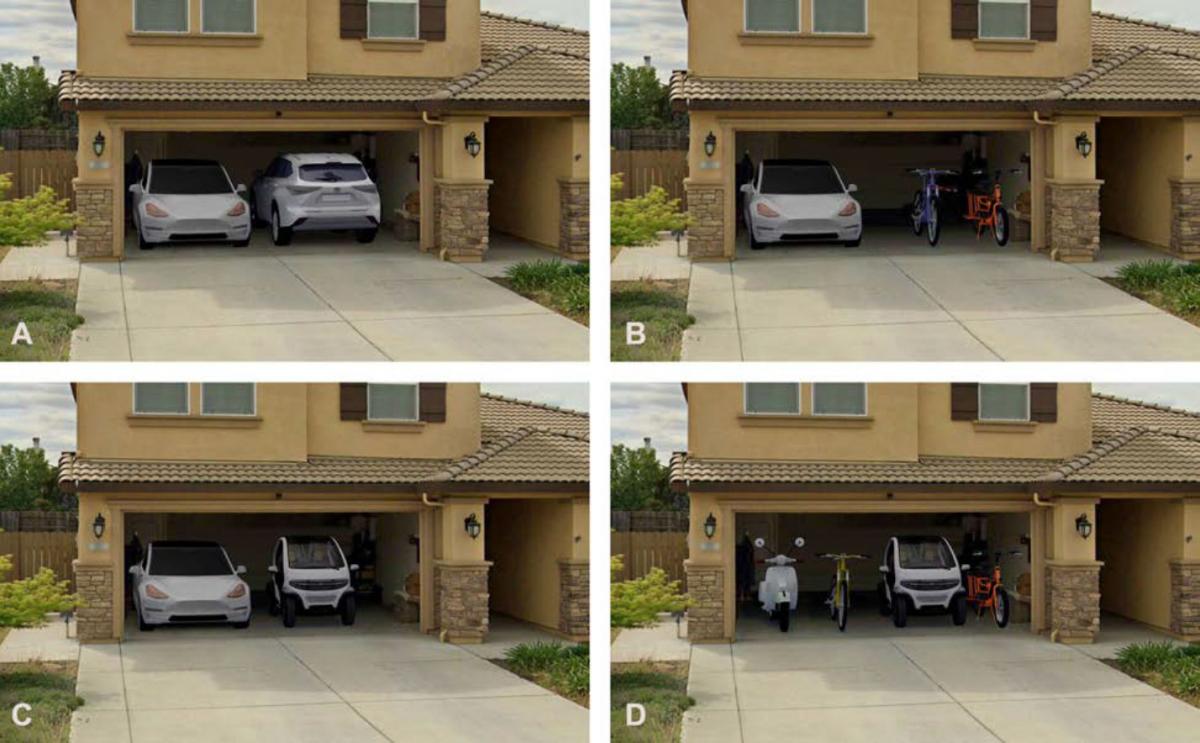

Research by Geoff Boeing of the University of Southern California found that street connectedness in America eroded from 1940 through the 1990s with the dissolution getting worse with time, but that trend started reversing after 2000 toward more street connectedness.7 Better internal connectedness of streets in subdivisions is an improvement. Nevertheless, the need remains to improve wider neighborhood connectedness through slower street speeds, separated bike lanes, and better intersection designs where streets exiting subdivisions end in T-intersections. In the United States, e-bikes are outselling electric cars and trucks. As demand grows for better access to local useful destinations via e-bikes and other Tier 1 modes, and street designs improve, many nearby residents will equip their garages with Tier 1 vehicles next to their Tier 2 ones. According to the American Automobile Association, the average cost of car ownership in the United States is more than $12,000 annually.8 Considering the rising cost of automobiles, replacing one car with a couple of e-bikes or a small NEV is a significant household cost reduction. And if the larger Tier 2 vehicle spends more time in the garage and less time on the street, it may outlive its owner. For even greater cost savings, some households could forego any personally owned Tier 2 vehicles and rent them as needed.

As more households choose to shop local via much smaller Tier 1 vehicles, land devoted to parking at destinations would shrink in size. This would free up real estate, putting land to more productive uses than storing cars. The ground area occupied by parked NEVs is as little as a third of the footprint of popular full-size cars; e-mopeds are much smaller still and bicycles can take one-tenth the space to park. In an unfolding Tier 2 world, parking garages will be under greater loads requiring more concrete as American vehicles get bigger, electrified, and thus heavier; cement accounts for 8 percent of GHG emissions. Structured parking for Tier 1 vehicles in Europe and Japan is not unusual and is much less an engineering marvel than the expensive concrete and steel-intensive structures built for Tier 2 vehicles. Tier 1 structured parking can also be much smaller for even greater cost savings.

Climbing hills

Another area in cities where Tier 1 vehicles could provide low-carbon mobility is in hillside neighborhoods. The assumption of much American development in recent decades is that high-horsepower Tier 2 modes of travel allow development to ignore topographic constraints. Whereas uphill travel discourages walking or bicycling, car travel has allowed real estate development outside flat urban centers in hilly areas, offering views as an amenity. Many of these areas are not far from centers; nevertheless, planners have exempted these areas from walking and bicycling. Evolving technology is introducing more powerful Tier 1 solutions for traveling up and down from these places, while Tier 1 travel maintains the incentive to be close to centers.

In the debate about whether future vehicles should be powered by electricity or hydrogen, the distinction between Tier 1 and Tier 2 clears up the debate. Long-distance travel calling for quick refueling at refueling stations would warrant hydrogen, but as we've seen, most travel is not long-distance. Local travel should be electric, with vehicles easily charged at wall outlets. Fueling bicycles and scooters with hydrogen makes no sense.

This is not to deny the value of Tier 2 vehicles; many people require them daily: home health care workers who care for a widely dispersed clientele, the infirm who need to be driven, traveling professionals who need a lockable vehicle for equipment and papers, day laborers, and construction workers. Yet even they don't need two-ton vehicles for every conceivable trip.

“Two-tier mobility” is a meme for thinking of the relationship of mobility and urban design. Influential memes like transit-oriented development, missing middle housing, complete streets, safe routes to school, and mixed-use development reside in the mind as placeholders for urban planning solutions orchestrating many coordinated changes—memes that aid constructive and efficient communication. Over 100 years ago, travel was multimodal: walking, bicycling, streetcars, trains, horses, and ferries. It's time to accelerate the change to a new multimodal transportation future that allows people to choose the low-carbon emitting vehicles appropriate to their local and distance mobility needs. Two-tier mobility as a meme can help us think and act anew.

Editor's note: This article addresses CNU’s Strategic Plan goal of advancing design strategies that help communities adapt to climate change and mitigate its future impact.

Notes

1 “Housing and the Strip: California's Untapped Opportunity,” CivicWell, 2022

2 Dan Sturges, Near to Far: A design for a new equitable and sustainable transportation system, 2023

3 “More than Half of all Daily Trips Were Less than Three Miles in 2021,” Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2022

4 “Tesla Model 3”, Wikipedia

5 Thea Riofrancos, et al, “Achieving Zero Emissions with More Mobility and Less Mining,” Climate + Community Project, UC Davis, 2023

6 Metropolitan Transportation Commission, “Pavement Conditions Index (PCI),” 2021

7 Geoff Boeing, “Off the Grid…and Back Again?”, 2020

8 AAA Automotive, “How Much Does It Really Cost to Own a New Car?”, AAA, 2023