Why we need to design community into neighborhoods

Improving the physical design of the built environment is not enough, argues author Seth Kaplan. He contends that healthy communities need formal and informal institutions that promote social interaction for humans to thrive.

“We can’t just build with a vision of the built environment; we need a vision of what it means for the built environment to encourage the social dynamics of a robust place,” Kaplan remarked on CNU’s On the Park Bench. “It’s not just about density and walkability. It’s about fostering a sense of place and uniqueness.”

Urbanists often discuss mixing uses and designing a public realm that promotes social interaction. If that’s robust neighborhood hardware, it can’t properly function without the software.

Kaplan is the author of Fragile Neighborhoods: Repairing American Society, One Zip Code at a Time. Americans used to live within “place-based networks” of clubs, churches, schools, commerce, and recreation that overlapped, wrapping individuals in social support. Local networks protected individuals from isolation and loneliness.

Those networks have largely disappeared, replaced by networks based outside the local community. We shop and interact online, extended families are scattered, government is often distant, and we commute long distances or work remotely. Kaplan says these arrangements serve some people well, but many more people fall through the cracks—especially the young, the old, the disadvantaged, and those going through crises.

“Whereas people used to have place-based institutions to encompass everybody in a place, now we have networks that leave a lot of people behind,” Kaplan says. “Many Americans are feeling more anxious, vulnerable, alienated, and mistrustful.” Those feelings are valid, because people are exposed to more risks when problems emerge without strong local networks.

Social isolation affects not just poor neighborhoods but also middle-class and wealthy communities. He quotes author Naomi Schaefer Riley: “Even at the upper echelons of society … these connections are weaker. They are fraying and people feel very worried about imposing on others and even embarrassed that they are not … totally self-sufficient.”

With suburban sprawl, we have built cities for isolation. In addition to missing physical connections, institutions and norms that create overlapping social connections in neighborhoods were also lost in the 20th Century, and that problem is less understood.

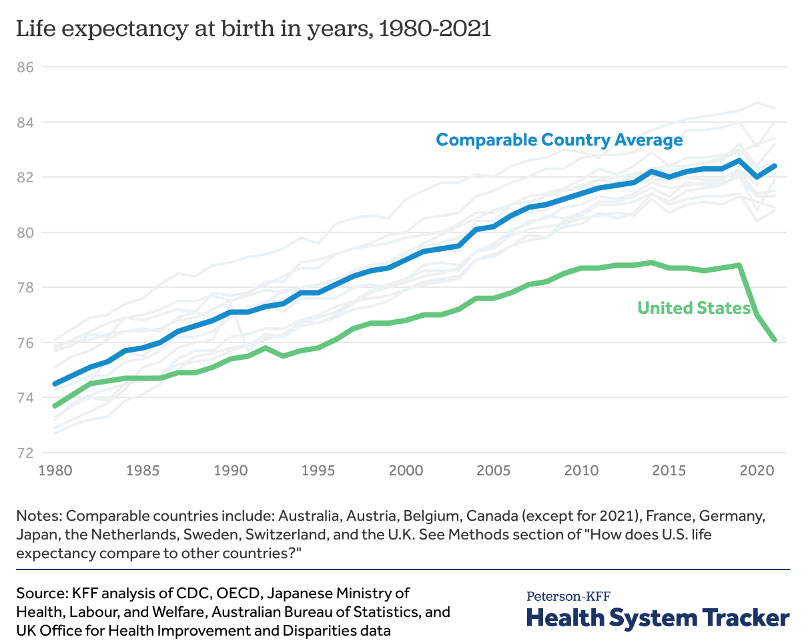

Earlier this year, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy raised the alarm of an epidemic of loneliness and isolation in the US, damaging health and leading many to an early grave (through drug overdoses, suicide, unhealthy habits, and a lack of informal oversight of vulnerable people). This pronouncement helped spark a national discussion on social connections. ‘What is missing in this conversation is a larger focus on place and place-based institutions,” Kaplan says.

He believes that physical neighborhoods could be a solution to this profound problem. “A flourishing society needs to be built on flourishing neighborhoods.” Kaplan, who attended CNU 31 this year, found his way to New Urbanism because he worries about American society. Kaplan is an expert in “fragile states,” which examines societal breakdown in nations. “I spent many years on this book because I have spent many years thinking about why countries work or don’t work, and I look at my own country and am very worried about our society.” Societal fragility is the top domestic problem in the US, he concludes.

Formal and informal institutions foster social life. Formal institutions include schools, churches, and civic associations. Informal institutions include the relative tendency to welcome and look out for neighbors. “Eyes on the street,” a concept promoted by urbanist Jane Jacobs, is an informal institution not merely about physical design, Kaplan notes: We have lost the norm of keeping an eye on the neighbors and children. Furthermore, local businesses are neighborhood institutions, whereas chain stores usually are not.

The trend toward renting may increase neighborhood turnover. And yet, “It's not owning or renting that matters; it is a commitment to a place,” Kaplan explains. Local schools and churches are very important in building community. Suburbs pose a particular problem because they lack centers for people to gather. Suburban retrofit needs to restore not just walkability but also social cohesiveness. He has four messages for new urbanists:

- Establish bounded neighborhoods with clear identities boundaries and uniqueness.

- Ensure every neighborhood has its own schools, parks, main streets, and meeting places.

- Build a wide range of housing and amenities to ensure a diverse population.

- Ensure charrette process is ongoing and nurtures lasting institutions and collective capacity (think about social institutions in the charrette process).

In Fragile Neighborhoods, Kaplan categorizes three neighborhood types: Robust, fragile, and “middle” neighborhoods. The robust kind can be studied and emulated for their social institutions. So-called Blue Zones, where people live longer, have strong institutions. In fragile neighborhoods, the social institutions are weak, and interactions are transactional. The middle neighborhoods are in between. They are in danger of becoming fragile but could also take less effort to become robust.

Watch the full video: