When planners walk on the wild side

“You never really feel like you’re building trails out here … Only finding them.” — Lawin Mohammad

“Like with a mandala or a labyrinth … I circle and pass similar points along the way, discovering slightly altered variations on a familiar theme … perspectives deepened, elaborated and embroidered, patterns unfolding so that larger meaning emerges.” — Roger Bell

There are right- and left-brain aspects to city planning and design. Of course, as planners, we need to gather data, assemble the base maps, conduct public processes, and meet engineering standards to be credible. Often—maybe all too often—the bulk of this work is done on a flat screen. Sure, there will be a windshield tour and, hopefully, a site visit. But in my experience, the planning team is not really kicking the dirt to get the feeling of the place. The process can often be stilted, particularly where budgets, deadlines, and maintaining professional decorum are prioritized. I’m here to make the case for a visceral, serendipitous, and, yes, playful side of the planning process.

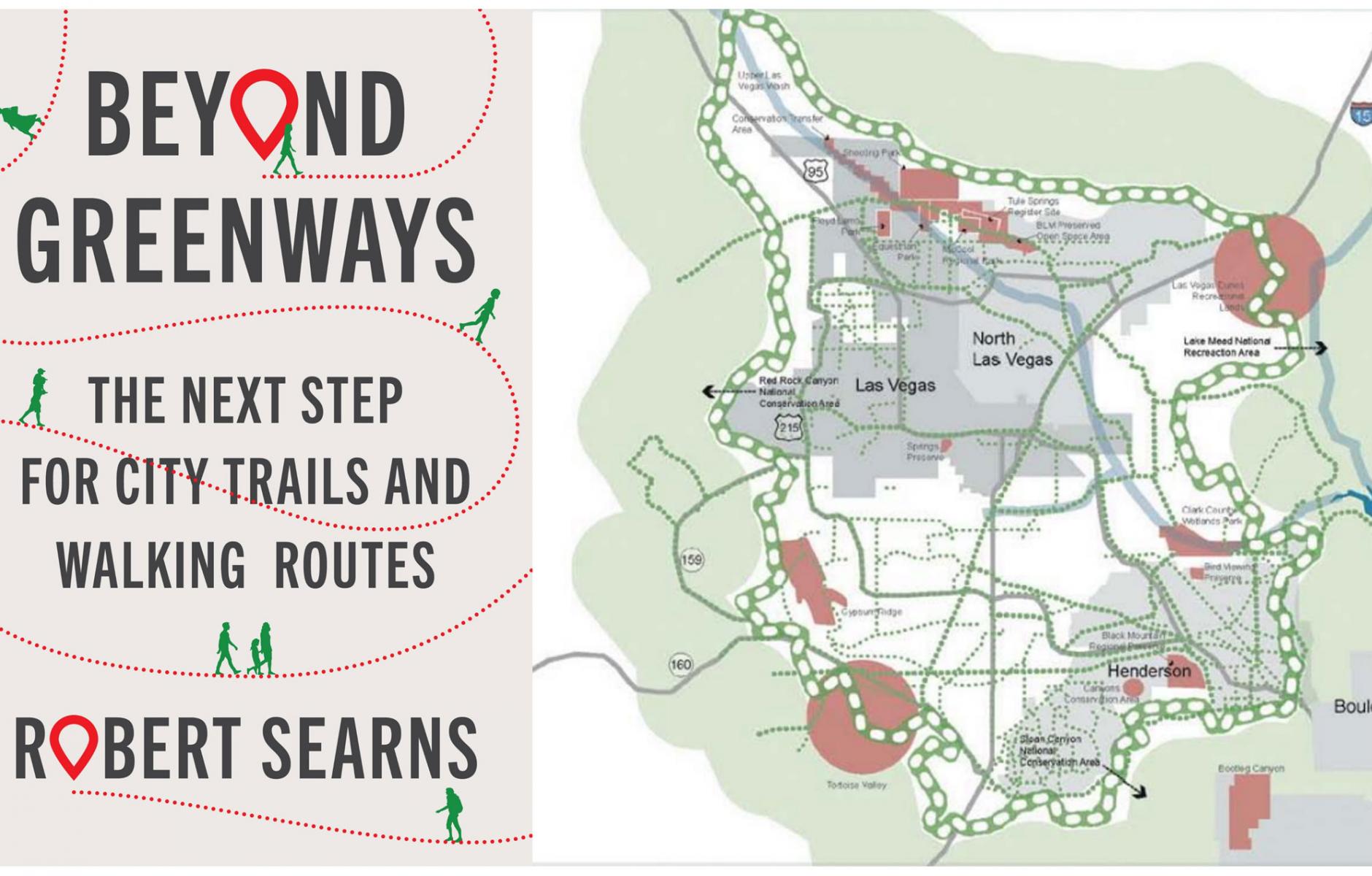

This perspective helped formulate the message in my book Beyond Greenways: The Next Step in City Trails and Walking Routes. Just released by Island Press, the book offers a new perspective on walkability—building the case for infrastructure in and around cities that can better accommodate, encourage, and enable more people to get outdoors routinely. The book also proposes a new urban design geometry: grand loops and town walks. The former are readily accessible pathways that circle the edges of cities showcasing the landscapes where the city meets the countryside. The latter are primarily branded in-town walking loops that highlight civic spaces, neighborhoods, or just pleasurable places to walk. Both elements aim to promote not only enjoyment, but also health and fitness and other benefits, including economic development and tourism.

These ideas sprung not from a planning study, but from walking out the door to see and feel the landscape. After four decades of planning and developing greenways—the primarily linear pathways that follow waterways or repurposed rail routes— I wondered what it would be like to walk around the edges of my city. And what could I discover by taking shorter loop strolls around town?

This wasn’t the first time I had had this inkling. A few years prior, I was part of a group working on the Southern Nevada Regional Open Space Plan, which sought to create a multidecade vision and framework for the rapidly developing Las Vegas Valley. A key focus was creating high-quality trail networks and preserving the character of surrounding mountain and desert landscapes. After several days of extensive fieldwork familiarizing ourselves with the features of the greater Las Vegas area, we were sitting in the project office musing about what we saw.

Stepping up to the pad of paper with the plans, someone said, “We need to lively this plan up—a big idea!” and drew a light bulb with a “smiley face.” I sat there looking at the circular outline of the “face” on the pad and pictured the Las Vegas strip in the center and began to picture the surrounding mountains, desert, Lake Mead, Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, and other close-in iconic features that surround the city. Still looking at the circle, I recalled a plan that landscape architect Bill Neumann and I had done for Silverthorne, Colorado, a couple of years earlier, where we proposed a trekking trail encircling that mountain resort community. Dubbed the Silverthorne Loop, that hiking path would wind around the edges of town through the surrounding hills, linking national forest and wilderness areas. Suddenly, the “smiley face” took on a new character. It could be a circular greenway—a grand loop around Las Vegas!

Two group members picked up Sharpies and began sketching the open space and park features that ring Las Vegas and drew a line connecting them. With their marker lines, they showed the image of a trail running around the edges of Las Vegas, where the city met the wildlands.

“What do we call this?,” someone blurted out. “We can’t call it a ‘greenway.’ It runs through the desert! That landscape is red and brown!” “Let’s call it the Vias Verdes Las Vegas,” I quipped. A month later, Chuck Flink, the main author of the plan, boldly wrote a recommendation calling for “the Vias Verdes Las Vegas,” described as “an attractive transitional belt between the desert backdrop and the urbanizing area encircling the entire valley defined by an interconnected trail system.”

When we put the idea in the plan, which was adopted in 2006, it was just one of the recommended items. I don’t think any of us expected the response we got to our bold idea. But then, a group called Outside Las Vegas enthusiastically embraced the Vias Verdes concept and set about to “develop a 113-mile . . . trail loop . . . around the Valley and link it to the to the existing trail network—connecting Southern Nevada from neon to nature.” More appropriately named the Vegas Valley Rim Trail, the project was unanimously approved by the Las Vegas City Council in 2012, and by 2021, it was more than 75 percent completed. Clearly, ideas can come from both expected and unexpected places. The message is, to find a way to plant the seed, nurture it with inspiration and credibility, and get the attention of groups with community ties, like Outside Las Vegas.

A similar story of serendipity took place in Tucson. Again, this was not a formal planning process, but two women with an idea and some leftover paint in a city storage building. History buffs, they envisioned a walking loop around Old Tucson that showcased the old barrios, iconic Spanish colonial buildings, restaurants, craft shops, and cultural destinations. They persuaded the city to take the blue-green paint and lay out a distinct easy-to-follow stripe that follows the sidewalks. Today the “Turquoise Trail” offers one of the best and most authentic ways to experience the city, benefiting both locals and tourists. It is one of the best examples of several town walks depicted in Beyond Greenways.

So, while my message here is about a new way of looking at pathways shaping urban design, it is equally about taking “walks on the wild side” when composing a plan, including taking the time to experience the place, think freely, even get silly—to have some fun. You never know what kind of unanticipated legacy might emerge.

From Beyond Greenways by Robert Searns. Copyright © 2023 Robert M. Searns. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.