The continuing relevance of Every Place Counts

CNU’s recent launch of the Freeway Fighters network is the most recent chapter of its long history of advocating for the transformation of in-city highways. This story includes many projects over decades, some little remembered, that have chipped away, over time, at the status quo of highways dividing and damaging cities.

In the summer of 2016, CNU partnered with the US Department of Transportation (US DOT) in a program called Ladders of Opportunity, Every Place Counts (EPC). CNU worked with transportation consultants, public officials, citizens in Nashville, Saint Paul, Philadelphia, and Spokane to address inequities caused by Interstate highways in the 20th Century.

The EPC sessions marked the first time that US DOT seriously examined how in-city highways impacted disadvantaged communities in multiple cities across the US—and how design could help to rectify the damage. Visioning workshops, such as EPC, notoriously tend to “sit on a shelf” rather than be implemented.

With the release of the Freeway Fighters network, I wanted to see whether any of the EPC design ideas made a lasting impact. The Freeway Fighters network is a fairly comprehensive list of 74 campaigns across the US where leaders, activists, and professionals are trying to remove or prevent in-city freeways, or mitigate the highway impacts through large caps.

EPC examined heavily traveled Interstates in four cities, and the solutions tended to revolve around highway caps that link severed neighborhoods on both sides of the highway. The success of Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park, over the Woodall Rogers Freeway, linking Downtown and Uptown, was fresh in the minds of DOT and transportation planners in 2016.

Cap over I-40 in Nashville

The EPC planning team proposed a highway cap over Interstate 40, west of downtown, near the historically Black colleges of Fisk University and Meharry Medical College. Referred to as the Jefferson Street Multimodal Cap & Connector, the project is being pursued by the City and its Department of Transportation and Multimodal Infrastructure (NDOT).

The CNU team envisioned the 4-acre cap, along Jefferson Street between 16th and DB Todd Jr Boulevard, in conjunction with proposed redesign of Jefferson Street, a thoroughfare with a storied 20th Century history of blues, jazz, and civil rights activism. The cap would connect the residential neighborhood of Osage/North Fisk to the educational institutions, creating a much-needed public space.

“Decades ago, Interstate 40 harmed and displaced an entire community,” said Nashville Mayor John Cooper. “Reconnecting North Nashville’s Jefferson Street community with our proposed cap is exactly the kind of project the Biden-Harris Administration’s American Jobs Plan will accomplish in cities like Nashville, correcting historic wrongs and bringing prosperity to our most vulnerable communities.”

This project represents what is likely the biggest impact of the EPC visioning sessions.

Land Bridge over I-94 in Saint Paul

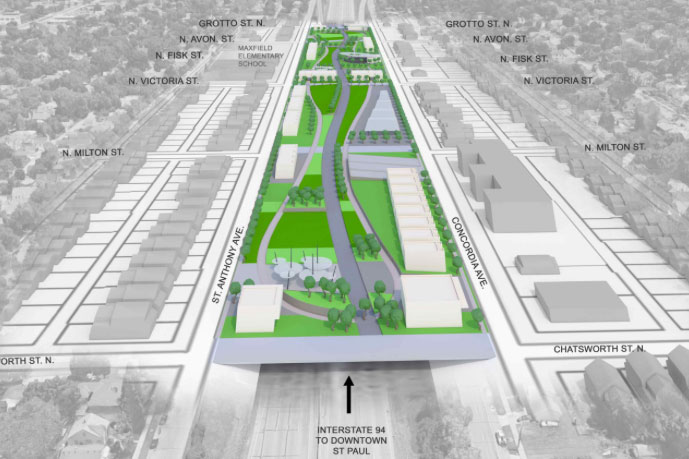

The idea for a bridge cap over I-94 in the Rondo neighborhood of Saint Paul, Minnesota, was floated by EPC. The original idea was a cap on either side of the Victoria Street bridge, including public space and low-rise residential units. The active Reconnect Rondo campaign has expanded this proposal to three blocks long—still envisioning a mixture of public space and buildings—and it is being called a Land Bridge.

Rondo, a historically Black neighborhood, was bisected by the highway and hundreds of houses were demolished. Reconnect Rondo has the support of a host of major organizations, including the City of Saint Paul, Minnesota Department of Transportation, Ramsay County Community and Economic Development, Urban Land Institute, and influential foundations.

Another, more radical vision, is being proposed by Our Streets MPLS. That group is promoting the Twin Cities Boulevard that would replace I-94 between Minneapolis and Saint Paul. That vision has to contend to the 150,000-170,000 cars per day that travel this section of Interstate. Theoretically, the Interstate could be rerouted on the current I-694.

Partial caps over I-676 in Philadelphia

Every Place Counts examined the corridor of I-676, a two-mile-long Interstate that goes through Chinatown in downtown Philadelphia, and proposed a series of partial caps along a seven-block area. The CNU team also proposed traffic calming on Vine Street—which parallels the highway on both sides. PennDOT has since completed two small caps at Logan Square, about a half mile to the west of Chinatown, and one very small cap in Chinatown, at the site of a new community center and residential building on the north side of the highway. There appears to be little interest in spending the necessary money to cap additional sections of I-676.

An inactive website is maintained on the campaign, with renderings. Most of the freeway fighting attention in Philly is focused on a planned and funded capping of I-95, about a mile away, set to begin construction later this year, which will better connect the city to the Delaware River. Not long ago PennDOT replaced seven bridges over I-676, which means that the state will likely not look again at this section of Interstate for a long time. Nevertheless, there is still interest in further repairing and capping this highway, which may activate plans down the road.

US 395 in Spokane, Washington

CNU’s report recommended that Spokane ditch a five-mile highway project, US 395, and replace that with a boulevard. This was the only EPC session that proposed to head off the damage from a planned in-city highway. Six years later, the highway is under construction, so EPC was unsuccessful in stopping it.

At the time, the highway was far along in planning and the political and bureaucratic momentum was strong, so a late vision to change that—even one sponsored by DOT—was a “hail Mary pass” from the get-go.

On the other hand—If not the for the EPC Design session, a boulevard would never have been proposed and examined. In the world of freeway fighting, you win some and you lose some, but the project that is never drawn has no chance of being built. That plan, which showed the feasibility (and the better quality of life) of a boulevard, was worth it even though the outcome was not changed.

The lesson from Spokane is that the boulevard idea was proposed too late. It needed to be on the table at least a decade before the highway construction began.

Every Place Counts was a landmark project for US DOT in recognizing the wrongful impact of 20th Century Interstates. These sessions were not always successful, but in two cases the ideas live on and stand a good chance of being built. These projects were not easy, either. At the time, these highways were on nobody’s list for demolition—and that is still mostly true.

Looking at a freeway that divides a city or neighborhood and envisioning urbanism or green space in its place is a radical act—but also founded on the reality of how cities work. To the extent that EPC has changed the course of policy and plans, that’s because of a growing recognition that urban neighborhoods are better off with surface streets and public spaces, not highways. Without exploring alternative scenarios, the status quo moves relentlessly forward. The status quo in the last 60-70 years has been freeways dividing city neighborhoods.