Spokane can avoid a big mistake

DOT released its Every Place Counts Design Challenge report yesterday, based on workshops in Spokane, Nashville, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis-St. Paul last summer. CNU helped organize those workshops, set up to explore mitigation of Interstate highways that have historically damaged minority and working class urban communities.

Many ideas were discussed, such as caps over freeways, complete streets, conversions of one-way to two-way streets, bicycle trails, public space, and redevelopment of disinvested areas.

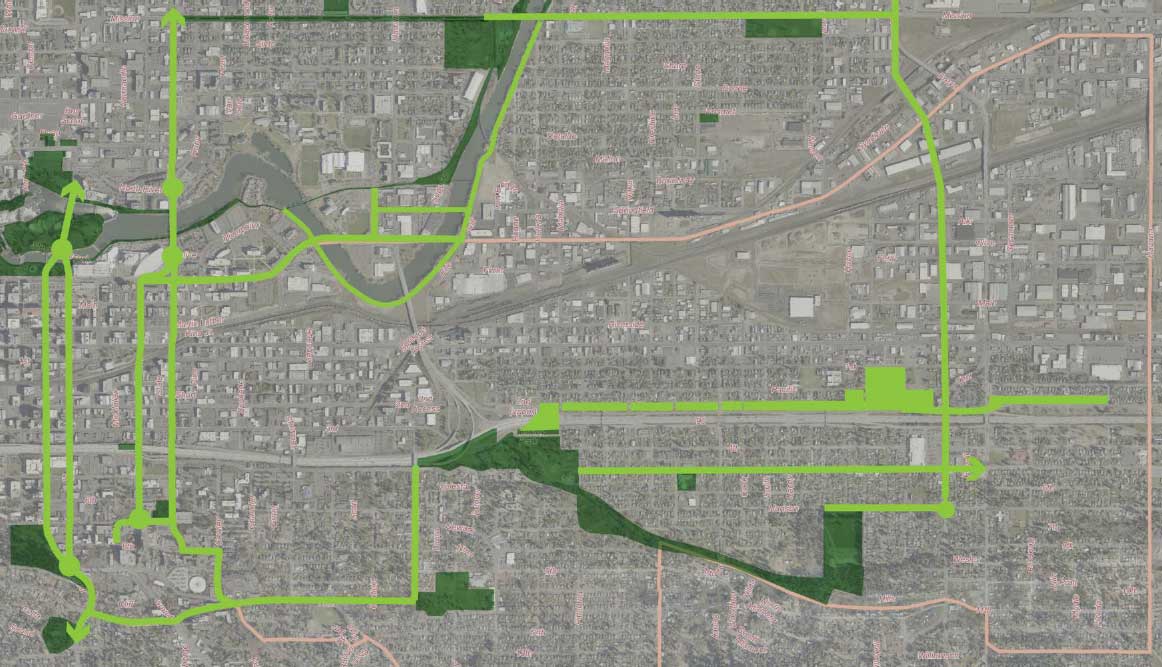

All of this is good, but it won't undo the enormous and sometimes unnecessary damage from these highways. Of the four cities, only Spokane has an opportunity to put the brakes on a current highway that will do damage all over again. The State of Washington DOT is planning to build the five-mile, $879 million US 395 North Spokane Corridor freeway through neighborhoods in the city, due for completion by the end of this decade.

A boulevard could handle the cars and trucks on US 395—taking traffic off of Division Street downtown, according to Ian Lockwood, a transportation engineer who helped lead the July workshop. On the first day, participants took part in visioning exercises, such as writing “postcards from the future.” One resident exclaimed, on the subject of why the new highway should not be built: "Are we going to be doing this again? Are we going to be sitting here in 25 years talking about how to mitigate the impacts of the North Spokane Corridor?"

A director of a nonprofit organization that serves businesses in a Spokane neighborhood damaged by I-90 came hoping that “this workshop will bring to light the fact that the new I-395 corridor might repeat the same issues caused by the I-90 corridor. Entire communities are disconnected from the few resources that are in the city, such as grocery stores.”

Explains Lockwood:

The North Spokane Corridor (I-395) is proposed to lead from I-90 to the north, and the idea is that truck drivers would trade goods up and down this corridor. But when you look at the volumes where the proposed highway is going, it’s around 8,000 vehicles a day. So there is really no transportation justification for turning the North Spokane Corridor into a freeway. This is a great opportunity for a city not to build a giant barrier in the community. And they don’t have to build the highway—it is a choice. If they do build it, they will create another very expensive piece of infrastructure that will probably be used primarily for local transportation. It would get the trucks off of a surface street that the city wants to be more of a main street. But a boulevard could accommodate the trucks and not have the problems that come with an in-city highway.

If you look at almost any US city you find corridors where the highways were proposed but not built, those corridors are far nicer today and far more valuable than they would be if the highway had been built. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see the pattern here. Is this North Spokane Corridor the only exception in the United States where the highway will be built though a city and it is not going to damage anything? Of course it is going to damage things. I really hope that Spokane looks at the pattern and doesn’t buy into the highway system thinking. The system is set up to reward long trips, fast trips, car trips. But I hope they just look at what happens in real cities and do what’s best for Spokane itself.

Although the case is compelling for not building this highway, it has been planned for 20 years and transportation officials are invested in the concept.

According to US DOT: If not for the Every Place Counts Design Challenge, the idea of evolving the unbuilt five miles of US 395 into a context-sensitive urban boulevard might never have been proposed. While stakeholder consensus did not coalesce around this concept—as conditions were not right to have a fully in-depth conversation—a public conversation can continue that might ultimately influence the final design of US 395 and the future of I-90 in a positive way.

Maybe the workshop will lead to a better, less destructive highway, but a boulevard would be an urban solution—based on the way traditional cities like Spokane are supposed to work. There is no compelling reason, except for sheer inertia, to put up a huge barrier that will last for a half century.

Even assuming US 395 is built, that doesn't negate what was accomplished in the workshops, according to planner Peter Park, who helped to lead them in Philadelphia and St. Paul.

"I think this initiative was strategically the right way to help guide the conversation," he said. "It starts with and prioritizes engaging the community meaningfully. A deliberate and sincere effort to engage communities leads to a broader, more effective set of solutions."