Complete streets: Visible counter to Covid recession?

The pandemic’s full negative impact on main streets is unknown, but significant. Many storefronts have closed and small businesses are hurting. We don’t know how many local employers will succumb to the economic hardships that communities have experienced.

Meanwhile, 2020 has been a year of eerily vacant downtowns—at times they resembled apocalyptic movies in which all of the people vanished.

Active storefronts are the primary amenity of main streets across America. Even after a vaccine makes urban places feel safe again, how many people will want to return downtown and stroll down streets with empty storefronts?

Depopulated main streets and empty storefronts could generate a negative feedback loop, causing more businesses to close and discouraging downtown visitors. Many downtowns currently have streets where traffic moves too fast for pedestrian comfort. Fewer pedestrians will make that situation worse—because drivers are prone to drive faster under such conditions.

Cities need to disrupt that feedback loop, and one way is to physically invest in streets to make them look and feel safer and more livable for people outside of cars. Cities can build “complete streets” to slow traffic, ease pedestrian crossings, and improve safety for bicyclists—through protected bike lanes and/or much slower vehicle speeds.

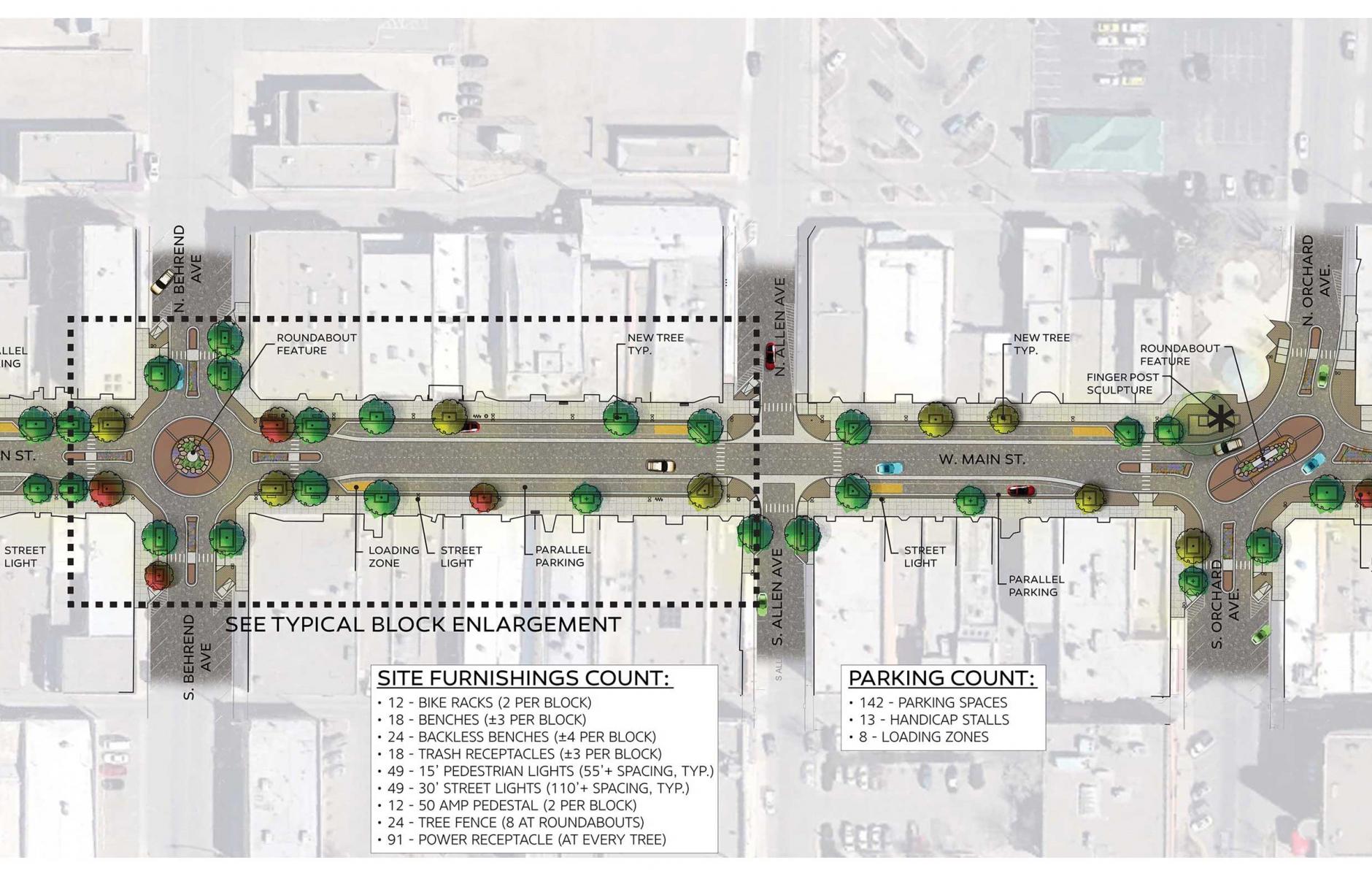

Farmington, a city of 45,000 in northwest New Mexico, is now completing such a project. A four-lane thoroughfare was reduced to two travel lanes, with pedestrian crossing distances cut by 50 percent or more. Two roundabouts were added, slowing traffic speeds to about 15-20 miles per hour. The $9.2 million project adds new lighting, landscaping, and sidewalks, and was “designed to enhance the appearance and appeal of the district by calming traffic, making it more pedestrian friendly and giving it facelift,” according to the Farmington Daily Times.

Such projects tend to provide a shot in the arm for downtowns, even in difficult financial times. A main street makeover in Lancaster, California, during the 2008-2009 recession, brought in more than 50 new businesses and generated a positive economic impact of $282 million. Even assuming a much smaller economic impact, a complete street project such as Farmington’s may help the downtown bounce back sooner after the coronavirus.

The timing for Farmington, with the completion during the pandemic, is perfect. The short-term danger of a complete street project is that the construction itself will pose a hardship on businesses. Fortunately, there is a strategy that can minimize the construction impact (in addition to the cost), and that is called “Quick Build.” Quick Build can accomplish many of the goals of complete streets, but projects are semipermanent (lasting 7-10 years, as opposed to 30). But the time and money spent is a small fraction, maybe 25 percent, of a permanent complete street project. If the project works as planned, cities could make it permanent over time.

A complete street has another significant benefit in a recovering economy—it’s a public works project that puts people to work during the construction phase. That’s a win-win.