Nine keys to safe downtown streets

Street life is dramatically impacted by the speed of vehicles. Whether they know it or not, most pedestrians understand in their bones that a person hit by a car going 35 mph is roughly seven times as likely to die than if the car is going 25 mph. Any community that is interested in street life—or human lives—must carefully consider the speed at which it allows cars to drive in places where people are walking.

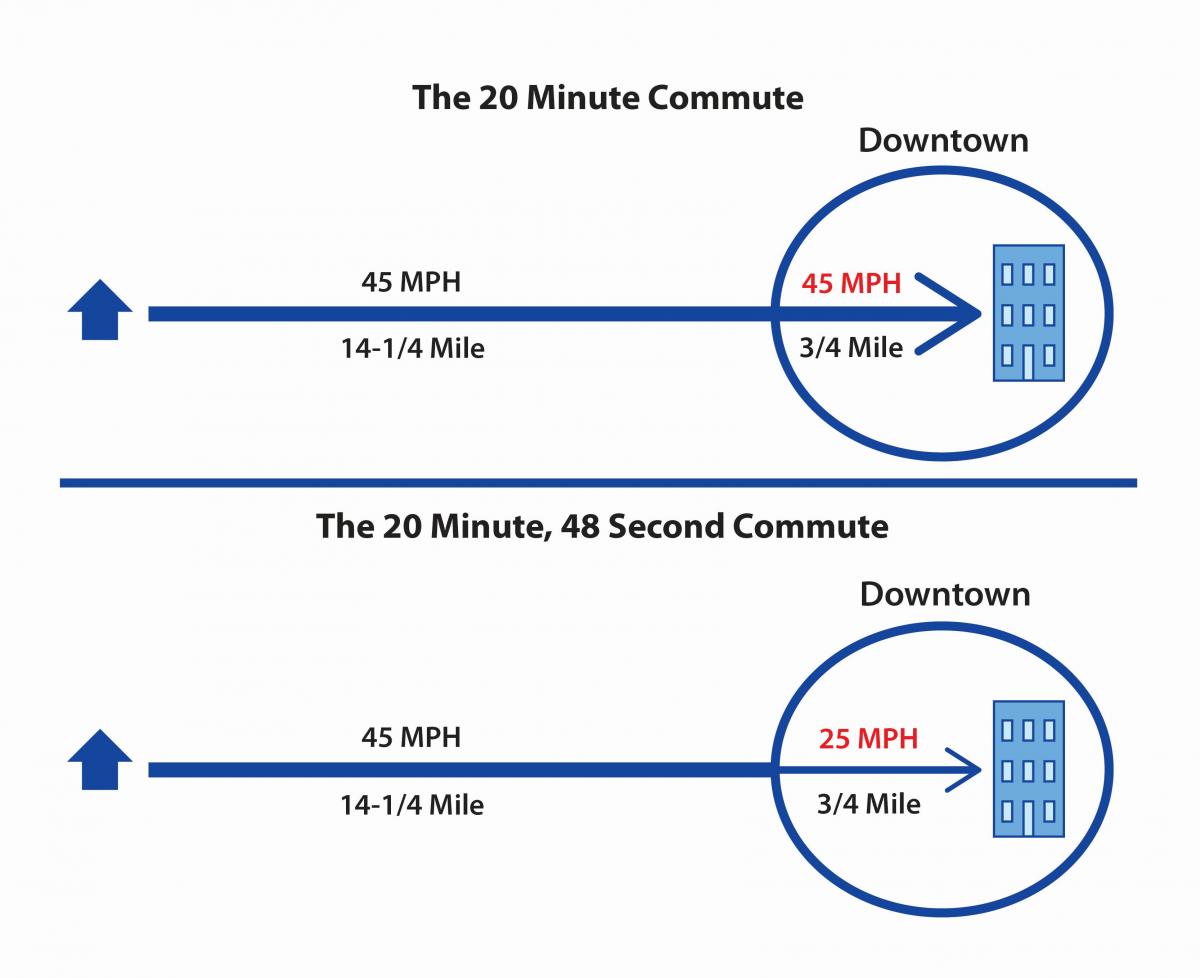

And in most American cities, the place where people are most likely to walk is downtown. Acknowledging this fact opens up real possibilities, as it allows us to have dramatic impact on walking while impacting driving time only minimally. By focusing on vehicle speeds downtown, we can make walking safer for the most pedestrians with the least amount of driver inconvenience.

The illustration below tries to make this point clear. It shows that the difference between an attractive and a repellent downtown may be less than a minute of drive time. Would most people be willing to spare 48 seconds each day if it meant that their city was a place worth arriving at? Probably.

If the key to making downtowns safe is to keep automobiles at reasonable speeds—and to protect pedestrians from them—then any serious downtown plan will take pains to address the principal factors that determine driver speed and pedestrian exposure. There are more than a dozen such factors, and most American cities are impacted by most of them. A recent downtown plan for Hammond, Indiana, revealed nine:

- The number of driving lanes;

- Lane width;

- One-way vs. two-way flow;

- Bike lanes;

- On-street parking;

- Street trees;

- Signals vs. stop signs;

- Pedestrian pushbuttons; and

- Street geometry.

Each of these is discussed below in the context of downtown Hammond.

- The proper number of driving lanes

The more lanes a street has, the faster traffic tends to go, and the further pedestrians have to cross. Removing unnecessary driving lanes frees up valuable pavement for more valuable uses, such as curb parking and bike lanes. In downtown Hammond, this conversation is most relevant as it pertains to Hohman Avenue, the primary commercial street, which holds at least four lanes of traffic through downtown.

South of the heart of downtown, it is clear that a “Classic American” 4-to-3-lane road diet is the proper solution, as it has been on dozens of main streets across North America. It comes as no surprise that these road diets save lives; when Edgewater Drive in Orlando was dieted, injuries to road users dropped by 68 percent. What many do find surprising, however, is that these diets do not reduce a street’s capacity. A study of 23 different 4-to-3-lane road diets across North America demonstrated, overall, a very slight average rise in the number of vehicles using the streets each day.

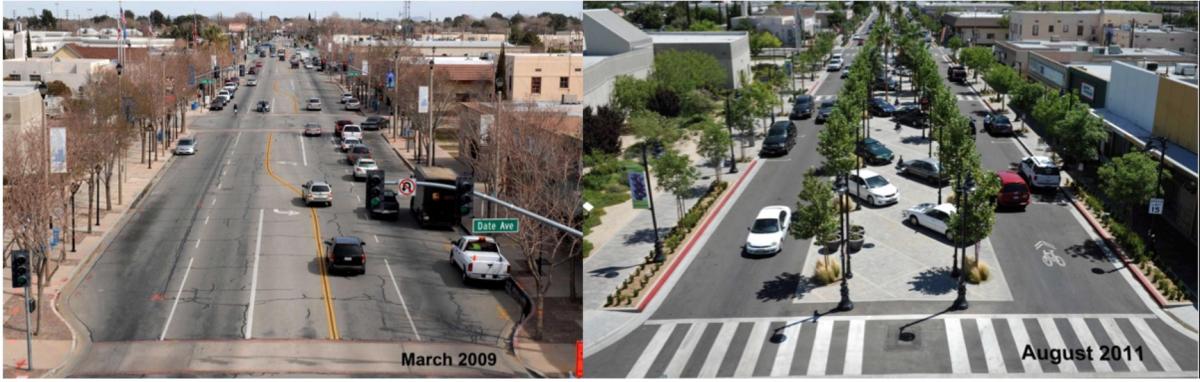

Four-to-three-lane road diets are an easy win, because they improve safety and make room for bike lanes without reducing car capacity. But in certain circumstances, more aggressive measures are warranted. Such is the case with the three main blocks of Hohman, the heart of downtown Hammond. This stretch of mostly empty storefronts is currently “on life support,” and needs drastic change to once again attract pedestrians.

A valuable model for these three blocks can be found in Lancaster, California, as earlier featured in Public Square. Here, a main street transformation completed in 2010 by Moule & Polyzoides reduced car crashes involving pedestrians by 78 percent while leading to the opening of 57 new businesses with an estimated economic impact of $282 million. This intervention took a five-lane street that was carrying 15,000 cars per day and reduced it two lanes carrying 11,000 cars per day.

As was the case in Lancaster, Hohman Avenue has multiple parallel routes onto which traffic can shift. It is important to understand that, while there are many ways to traverse Hammond from north to south, there is only one place to bring downtown back to life, and that is along Hohman Avenue. Happily, City leadership has embraced this conclusion.

- Lanes of proper width

Different-width traffic lanes correspond to different travel speeds. A typical American urban lane is 10 feet wide, which comfortably supports speeds of 35 mph. A typical American highway lane is 12 feet wide, which comfortably supports speeds of 70 mph. Drivers instinctively understand this connection between lane width and driving speed, and speed up when presented with wider lanes, even in urban locations. For this reason, any urban lane width in excess of 10 feet encourages speeds that can increase risk to people walking.

Many streets in downtown Hammond contain lanes that are 12 feet wide or more, and drivers can be observed approaching highway speeds when using them. It is surprising to learn, then, that the correlation between lane width and driving speed, crash frequency, and crash severity is a very recent discovery of the traffic engineering profession, and contradicts decades of conventional wisdom within that profession. Even today, many traffic engineers will still claim that wider lanes are safer. This understanding is accurate when applied to highways, where most people set their speeds in relation to posted speed limits. But on city streets, most people drive not the posted speed, but the speed which feels comfortable, which is faster when the lanes are wider. Fortunately, a number of recent studies provide ample evidence of the dangers posed by lanes 12 feet wide and wider.

In acknowledgment of this body of research, numerous organizations and agencies, like NACTO (The National Association of City Transportation Officials), have recently begun to endorse 10-foot lanes for use in urban contexts. NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide lists 10 feet as the standard, saying, “Lane widths of 10 feet are appropriate in urban areas and have a positive impact on a street’s safety without impacting traffic operations.”

This same conclusion was reached by ITE, the Institute of Transportation Engineers. According to the ITE Traffic Engineering Handbook, 7th Edition, “Ten feet should be the default width for general purpose lanes at speeds of 45 mph or less.” In this Plan, every street with lanes more than 10 feet wide is redesigned to the proper dimensions. (Worth noting is that the 10-foot dimension applies to busy urban streets, and that quiet residential streets gain safety by being even narrower.)

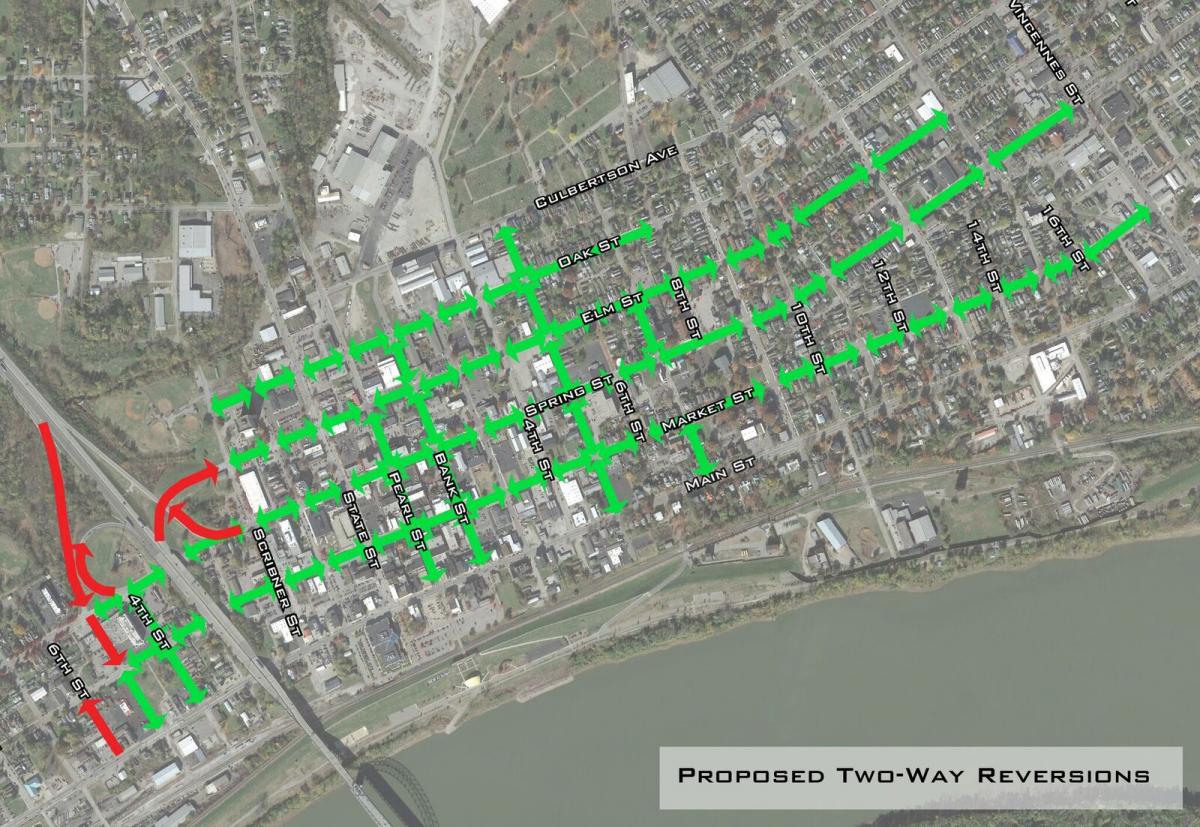

- Avoiding one-ways

People driving tend to speed on multiple-lane one-way streets, because there is less friction from opposing traffic, and due to the temptation to jockey from lane to lane. In contrast, when two-way traffic makes passing impossible, the driver is less likely to slip into the “road racer” frame of mind. Also, drivers turning onto one-ways from side streets often do so looking over their shoulder, and not at the crosswalk in front of them.

One-ways also have a history of damaging downtown retail districts, principally because they distribute vitality unevenly, and often in unexpected ways. They have been known to harm stores consigned to the morning path to work, since people do most of their shopping on the evening path home. Learning from the damage wrought by the one-way conversion, dozens of American cities are reverting these streets back to two-way.

In downtown Hammond, Russell Street passes one-way east in both a one-lane and a two-lane configuration. Where it is one lane wide, that extra-wide lane encourages speeding. Where it is two lanes wide, the extra lane encourages both speeding and jockeying from lane to lane. For both of these reasons, it makes sense to revert Russell Street back to two-way traffic.

- Including bike lanes

Cycling is the largest planning revolution currently underway—in only some American cities. The news is full of American cities that have created significant cycling populations by investing in downtown bike networks. Among the reasons to institute such a network is pedestrian safety: bikes help to slow cars down, and new bike lanes are a great way to use up excess road width currently dedicated to oversized driving lanes. When properly designed, bike lanes make streets safer for people who are biking, walking—and driving.

Experience in a large number of cities is making it clear that the key to bicycle safety is the establishment of a large biking population—so that drivers expect to see them—and, in turn, the key to establishing a large biking population is the provision of buffered lanes, broad lanes separated from traffic, ideally by a lane of parked cars. In one study, the insertion of buffered bike lanes in city streets was found generally to reduce injuries to all users (not just bicyclists) by 40 percent.

Hammond, like most American cities, has many streets with lanes that are either too wide or too great in number. Right-sizing these streets provides ample opportunities for bike lanes, most of which can be fully buffered.

- Continuous on-street parking

Whether parallel or angled, on-street parking provides a barrier of steel between the roadway and the sidewalk that allows people walking to feel at ease. It also causes people driving to slow down out of concern for possible conflicts with cars parking or pulling out. On-street parking also provides much-needed life to city sidewalks, which are occupied in large part by people walking to and from cars that have been parked a short distance from their destinations.

On-street parking is essential to successful shopping districts. According to the consultant Robert Gibbs, author of Urban Retail, each on-street parking space in a vital shopping area produces between $150,000 and $200,000 in sales.

Several streets in downtown Hammond have lost a significant amount of their on-street parking to driving lanes. Some of these streets, most notably the north end of Hohman, have no on-street parking at all. Bringing missing parking back will contribute markedly to the safety and success of downtown.

- Providing continuous street trees

Relative to pedestrian safety, street trees are similar to parked cars in the way that they protect sidewalks from moving cars. They also create a perceptual narrowing of the street that lowers driving speeds. But they only perform this role when they are sturdy, and planted tightly enough to register in drivers’ vision.

Recent studies show that, far from posing a hazard to motorists, trees along streets result in fewer injury crashes. One such study, of Orlando’s Colonial Drive, found that a section without trees and other vertical objects near the roadway experienced 12 percent more midblock crashes, 45 percent more injurious crashes, and a dramatically higher number of fatal crashes: six vs. zero.

Providing street trees in urban sidewalks where they don’t currently exist is expensive. While a continuous tree canopy is a good idea throughout downtown Hammond, the insertion of new street trees makes the most sense in those locations where streets are being rebuilt or created from scratch, where indeed they must be required.

- Replacing unwarranted signals with four-way stop signs

For many years, cities inserted traffic signals at their intersections as a matter of pride, with the understanding that a larger number of signals meant that a place was more modern and cosmopolitan. Recently, that dynamic has begun to change, as concerns about road safety have caused many to question whether signals are the appropriate solution for intersections experiencing moderate traffic.

Research now suggests that four-way stop signs (or three-way at T intersections), which require motorists to approach each intersection as a negotiation, turn out to be much safer than signals. Unlike with signals, no law-abiding driver ever passes through the stop-sign intersection at more than a very low speed. Eye-contact among users is considerable.

When a state ruling mandated the removal of traffic signals from 462 low-to-moderate-traffic intersections in Philadelphia, overall crashes dropped by 24 percent. Severe injury crashes were reduced 62.5 percent overall, and severe pedestrian injury crashes fell by 68 percent.

It is true that motorists have to pause more in street networks with stop signs. But these pauses are all quite brief. Never does the driver have to sit and wait for a light to turn from red to green. Surprisingly, more stops can mean a quicker commute.

In downtown Hammond, seven intersections have been identified where signals are eligible for replacement with all-way stop signs. Four of these are made possible by the redesign of Hohman Avenue from a highway into a linear plaza.

- Replacing pedestrian push-buttons with automatic walk signals

Pushbutton crossing requests are another feature that impacts the pedestrian experience. While they were ostensibly created to assist people walking, they more often have the opposite effect.

Typically, the introduction of a pushbutton means that, unless they push the button, people walking are not given an ample crossing time. In some cases, the walk signal never appears at all unless the button is pushed. Quite often, the pedestrian is frustrated by the impression that the button is ineffective. Little wonder, then, that most walkable cities don’t have them.

The traditional and proper signalization system for intersections is called a “concurrent regime.” Under a concurrent regime, pedestrians receive the walk sign when cars get the green light, and vehicles must wait for pedestrians to clear the crosswalk before turning. This system is extremely convenient for people walking: if they can’t cross one leg of an intersection, they can cross the other. The concurrent regime is the reason why it is possible to walk diagonally across Manhattan without ever stopping.

Like most downtowns, Hammond should replace its pushbuttons with concurrent regime signalization, supplemented with LPIs, Lead Pedestrian Intervals. The LPI gives pedestrians the walk sign a few seconds before the light turns green, allowing them to claim the crosswalk before it is encroached by turning vehicles. For crosswalks at which many people are walking, LPIs are the safest and most convenient solution.

- Avoid swooping geometries

Walkable environments can be characterized by their rectilinear and angled geometries and tight curb radii. Wherever suburban curving geometries are introduced, cars speed up, and pedestrians feel unsafe. Rarely are such swoops found in successful downtowns.

Such a condition can be found in along Hohman Avenue, which Rimbach and Fayette Streets once intersected at two separate T intersections, and where Rimbach has been reconfigured to swoop into Fayette. Returning this intersection to its original configuration will make it more welcoming to pedestrians, while discouraging the fast driving that currently occurs there.

Issues prevalent elsewhere

The paragraphs above cite examples from Hammond, Indiana, in order to make the discussion more real, but the same issues exist almost everywhere, at least in North America. Other cities struggle with additional challenges. The above nine issues are the ones that matter in Hammond, but they come from a list twice as large. Discussed at length in the book Walkable City Rules, other factors include:

- Downtown-wide speed limits;

- Red-light and speed cameras;

- Presence and design of turn lanes;

- Rear-angle vs. front-angle parking;

- Slip lanes and sight triangles;

- Bulb-outs and neckdowns;

- Sidewalk depth and parklets;

- Building setbacks and street lighting;

- Curb cuts and upright curbs;

- Complex vs. simple intersections;

- Centerline removal;

- Crosswalk design;

- Shared space and naked streets; and

- Pedestrian-only zones.

All of these factors matter. Attacking them comprehensively in your city will create street life, and save human lives.

We just learned last week that the city of Oslo experienced zero pedestrian or cyclist deaths in 2019. The same outcome is possible in North American cities, but only if we understand the conversation presented above, and commit to making the changes it describes.

Note: This article is excerpted and modified from the Downtown Hammond Master Plan.