Cities benefit from restoring two-way traffic

Midwestern cities report significant success restoring two-way traffic on one-way streets. New Albany, Indiana, switched more than four miles of city streets while implementing traffic-calming measures made possible by the conversions. Police Chief Wm. Todd Bailey reports, in a public letter, that the two-way street designs are “overwhelmingly” superior in the following respects:

- Accidents involving pedestrians are down.

- Speeding is reduced. The previous one-way configurations allowed motorists to travel “well above posted speed limits,” Bailey says, whereas the new designs “have slowed traffic as planned.”

- Motor vehicle crashes are down, especially injury crashes, compared to previous years.

- In general, the streets work better. “It has been our observation that the new designs allow for motor vehicles, bicycles, and pedestrians to all interact in a much smoother manner,” he says. “Additionally, due to the new design, when we experience a problem, we are provided with more options to redirect traffic. The design has also facilitated a better response from police and fire as those options have multiplied.”

The New Albany restorations included street repaving, new signs, signal modifications, crosswalks, landscaping, markings, and other improvements downtown and in adjacent neighborhoods, designed by planner Jeff Speck of Speck & Associates with engineer Paul Moore of Nelson\Nygaard (now with Arup). Speck promotes restoring two-way traffic as a way to make cities more walkable, and has completed similar work in Cedar Rapids, Iowa—also detailed in this article—Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Lowell, Massachusetts, Davenport, Iowa, and Boise, Idaho.

Two-way restorations are a nationwide trend. In late June, Atlanta City Council approved the change to the four-lane stretch of Baker Street, more than a mile long near downtown and costing $2.67 million, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (The mayor vetoed the council's decision this week). In Speck’s 2018 book Walkable City Rules, he lists 78 cities that have successfully restored streets to two-way travel.

There was a time when all city streets were two-way—but between 1950 and 1980, Speck documents an “epidemic” of conversions to one-way streets in cities all across America. Although one-way systems can sometimes work well—particularly if there is a dense network of narrow streets—mostly these conversions greatly damaged downtowns by killing off retail and turning city streets into, essentially, surface highways, Speck writes.

While many cities are reversing this trend, few cities have done so more broadly and quickly than New Albany, population 36,000, just across the river from Louisville, Kentucky—a metro area with 1.29 million people.

“I was hired by New Albany in 2014 to redesign their downtown street network in the face of a very real threat: the new tolling regime planned for crossing the Ohio River into Louisville was going to cause a lot of cut-through traffic to inundate New Albany, the site of the one free bridge,” explains Speck. “They understood that their one-ways attracted speeding, and also had a sense that their considerable excess capacity—which I demonstrated to them—was quickly going to fill up with new car trips if they did not constrain them to hold roughly the current volume.” The project was largely completed in 2017 at a cost to the city of $1.475 million, aided by $2.8 million in federal funds.

New Albany’s biggest challenge, after nearly 60 years of one-way traffic, was to get residents to see the benefits of greater downtown access and visibility from more pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly two-way streets, John Rosenbarger, the city public works projects supervisor, told Public Square. “You need a city staff that is committed to the change, and a mayor who is willing to take it on,” he says. “The reversion was smooth with minimal issues. Merchants like it, especially where their visibility increased from the previously invisible side.” Based on its recent experience, New Albany is looking to convert another mile of one-way streets to two-way.

Cedar Rapids

Cedar Rapids, Iowa, a city of 132,000 people, is nearly finished restoring more than 5 miles of streets to two-way travel.

The restorations are part of a larger effort to make downtown more friendly to pedestrians, motorists, bicyclists, and businesses, according to The Gazette, a local newspaper.

“These two-way conversions are a critical piece to make it feel like a place where you would want to live and walk around and feel safe,” Jennifer Pratt, the city’s community development director, told The Gazette.

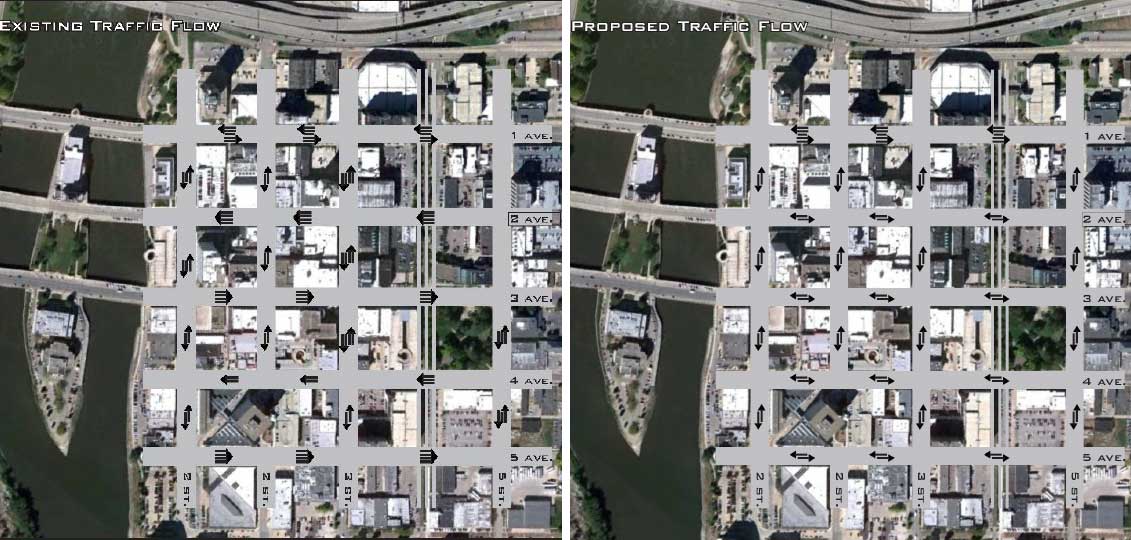

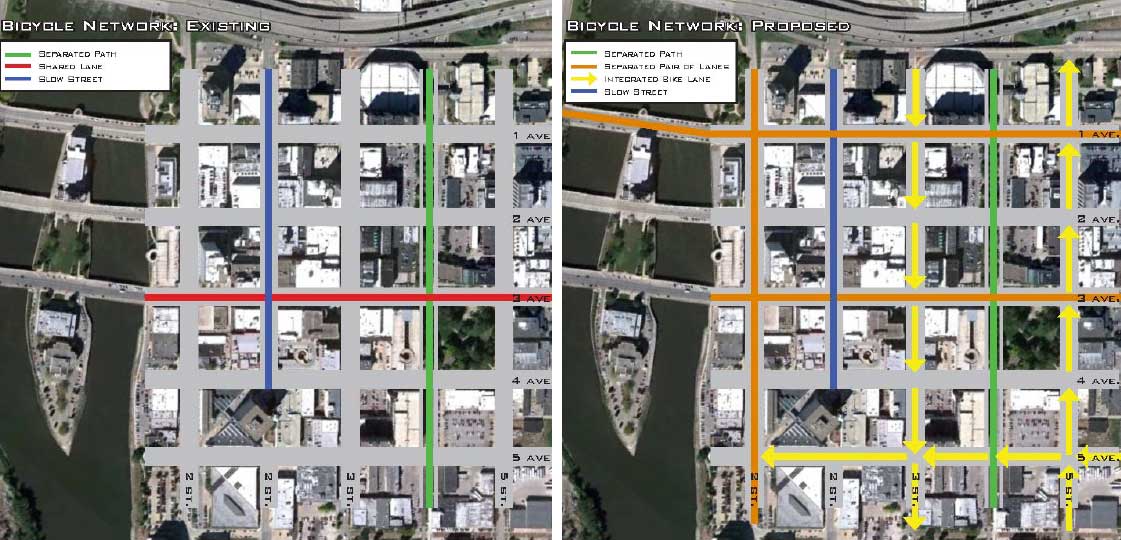

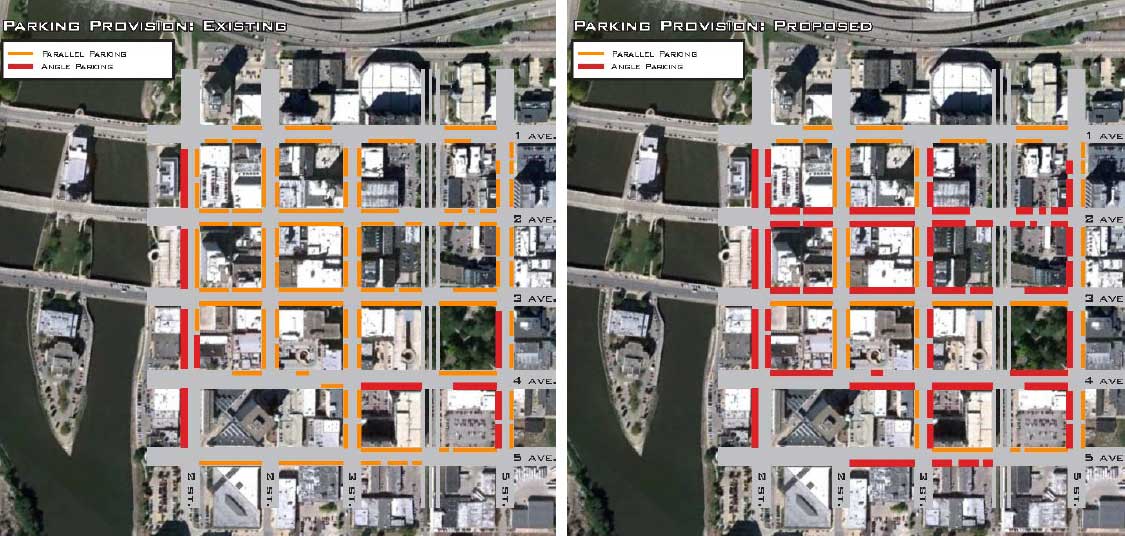

Speck worked with the city to create a Complete Street Master Plan, adopted in 2015, and to redesign all streets in the 20-block downtown core. “My plan turned a downtown that was almost all four-lane and half one-way into one that is almost all two-lane and all two-way, adding a ton of on-street parking and cycle facilities,” says Speck. “We also converted a number of signals to all-way stops, as I usually do; turning one-ways into two-ways usually makes this possible.”

Eliminating unnecessary travel lanes allowed for more cycle facilities along with angle-in parking that supports retail. The four-way stops discourage speeding of drivers trying to get through green lights, are pedestrian-friendly, and save the city money. “In addition to saving lives, all-way stops can make paths through a downtown more efficient by eliminating the need to sit idling at red lights,” he explains. Restorations and redesigns have been implemented over a five-year period, using local money, as streets needed to be resurfaced.

The Cedar Rapids streets were converted to one-way in the 1960s to accommodate downtown through-traffic; however, the 1970s completion of Interstate 380 took away most of this traffic—leaving downtown with relatively low-volume, high-speed, one-way surface streets. The speeds added to the difficulty of crossing on foot. Since the change, traffic has slowed on streets that have been converted to two-way, the police department reports.

“All we’re doing is going back to what was originally intended, for all these one-way streets, they were all designed to be two-way streets,” local historian Mark Stoffer Hunter told The Gazzette. “What I like about converting back to two-way is that all the local architecture, all the buildings and houses, are all designed to be looked at from both directions.”

Despite scores of examples of successful to one-way to two-way transformations, Speck notes that many cities still face considerable inertia when it comes to making this change. Research suggests that more cities would benefit from restoring two-way travel.

Across from New Albany, Louisville has a downtown that is still mostly one-way. Yet when the city did restore a pair of streets to two-way travel, a study found substantial improvements to livability. John Gilderbloom of the University of Louisville and William Riggs of Cal Poly San Luis Obispo looked at four adjacent one-way streets in Louisville, two of which were restored to two-way traffic in 2011. The converted streets “experienced a collective drop in total collisions of about 49 percent, despite attracting more vehicles than before the change,” Speck notes. Accidents on the streets that stayed one-way rose by 10 percent in the same time period.

Crime fell by 23 percent on the restored streets—compared to a 3 percent rise on the streets that did not change. The researchers attribute the crime drop to better visibility from slower-moving, two-way traffic—one-way streets provide “shadow zones” between buildings where people can hide. The safer streets rose in value, providing more tax revenue to the city.

Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, just north of the central business district, suffered from hundreds of vacant and dilapidated historic buildings two decades ago. “The city is riding a wave of success spurred in large part by the transformation of this community from Cincinnati’s most dangerous neighborhood to a hipster haven,” Speck writes in Walkable City Rules. “This revival was centered on Vine Street, and began when the city reverted the street to two-way traffic in 1999.” Ironically, the city has been pondering restoring two-way traffic on nearby Main Street for more than a decade, but officials have been unable to pull the trigger. Maybe the ongoing successes in cities like New Albany, Cedar Rapids, and Louisville will embolden Cincinnati and other cities to restore more two-way traffic.