Great idea: The polycentric region

In celebration of the 25th Congress for the New Urbanism, Public Square is running the series 25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism. These ideas have been shaped by new urbanists and continue to influence cities, towns, and suburbs. The series is meant to inspire and challenge those working toward complete communities in the next quarter century.

The polycentric region is the superstructure of good urbanism. The idea envisions and supports all community and place types such as hamlets, villages, towns, neighborhoods, and cities—ideally connected by transit. The polycentric region connects farm to table, nature to urban core, home to workplace, and helps people to navigate from town to city, and from neighborhood to neighborhood. But bringing that vision to reality poses many challenges in the 21st Century—from rapidly changing transportation technologies to the politics of land use.

Public Square editor Robert Steuteville interviewed Susan Henderson, principal and town planner with urban design firm Placemakers, and David Dixon, senior principal and urban design group leader with Stantec, an international design and engineering firm, on the subject of regional planning and urbanism.

How difficult is it to implement urbanism on a regional scale?

Henderson: There's two sides to that coin. Politically it's easier to solve the regional scale because people aren't as vested in policy, and so it's easier to get a general consensus on a big vision. Implementation is more challenging because if you're not in California or Hawaii or Florida where you have concurrency requirements, then it's surely at the whim of the elected official as to whether or not they implement the policy.

The Charter talks about the metropolis as made of multiple centers that are cities, towns, and villages, each with its own identifiable center and edge. Where does that exist in America today, and how can you build such regions again?

Henderson: In more rural areas, I think you definitely can see that. For example, we did the regional plan for southern New Mexico, including El Paso as the metropolis, and Las Cruces as a mid-size city, and then lots of towns and villages. But I think in the really urbanized portion of the country, things do tend to bleed together, and there are no longer those distinctions.

Dixon: For a very long time, the economics of real estate development was not creating a humanist, people-centric, community-rich way to live. But as our knowledge economy takes over, as our demographics shift dramatically and we're not producing more children, most of our new households are singles and couples, not families with kids. Singles and couples are more interested in community, more interested in living in towns or villages or cities that have lively, walkable centers, and they spend their money that way. They want to live close to the core in a walkable place, and they want a job that's close, so jobs are following them.

That's true, but it doesn’t necessarily create an urban form. We have metropolitan regions where the DNA—the codes—is still replicating sprawl, and we have thoroughfares that are the bones of sprawl. So how do you build a region of distinct cities, towns, and villages when you have that reality?

Dixon: Our demographics and our real estate economy and economic development and what communities compete for—jobs and investments and tax base—are now basically all going in the same direction that New Urbanism wants to take us. So instead of fighting the tide, we can work with the tide.

Henderson: Actually, I think that may be very, very true in places like Boston, and DC, and even Los Angeles, but in mid-sized big cities and smaller, the suburban mindset still has an incredible hold over building and development.

Dixon: We are working now in Baton Rouge and Elkhart, Indiana, and suburban Boston, but also suburban Ohio, and Charlotte, and Roanoke, Virginia—the county, not the cute downtown—where these same forces are at work and even if the mindset hasn't changed, the market has. So we just don't have a lot of demand anywhere for a whole new generation of single-family houses. Maybe there’s demand for a master-planned development in specialized cases, but the market of sprawl for sprawl’s sake has really dried up. Elkhart, Indiana, has to build a knowledge economy too. That’s not just about reviving downtown, it's about reviving the urban neighborhoods around it. The potential for the market and local government to support new urbanist values is on the rise and will rise significantly going forward.

I am optimistic about the fundamental reversal in the underlying forces of sprawl. That has set the stage for much more positive outcome. And one change that people really do like, is the idea of preserving nature, of preserving access to green space. And when people see that housing demand is shifting dramatically from single-family to multifamily, they understand that "Oh, we can realistically concentrate our growth." There is demand to redevelop strip shopping centers, for example, to create new town centers.

The Charter says the metropolis has a necessary and fragile relationship with its agrarian hinterland and natural landscapes. So what is the best way to nurture that relationship in a region?

Henderson: We've done a lot of county-wide codes where the biggest barrier to appropriate conservation of working agriculture and open space is the definition of the lot size of agriculture. And in the vast majority of the Thomas Jefferson-plotted and homesteaded United States, 40 acres was a homestead. Here in the west, it's more like 140 acres to be able to survive. We have discovered that in many places, farmers' financing is directly tied to maximum developable capacity. And the Farm Bureau is largely the culprit because they have values of farmland based on the subdivision potential. And many farmers have no intention of subdividing, but their annual cash flow depends on the mortgage and how much of a credit line they have with the Farm Bureau based on development capacity. As a result you get a five-acre—in many places, even one-acre—designations for the parcel size for agriculture and then that makes it possible to have the devastation of rural sprawl.

Dixon: I gave a talk in Seattle a number of years ago, and the fellow who spoke before me said the best way to preserve the Cascade Region, preserve their nature, is make the city a really great place to live and make density work. I was really intrigued by that. New Urbanism is unbelievably good at helping people have a community conversation about the form and character of change. We're going to continue to grow, particularly regions that are economically successful, and this is going to put pressure on agricultural land and nature around cities, and blur those edges if we can't find ways to bring this growth into our cores, to revitalize and reinforce villages, towns, cities, and centers. That’s where the market wants to go. It's not like you have to drag people in. And New Urbanism is great at showing how this new density can be familiar. It can line streets, it can create front doors along the streets. It has a character that's about people and not about making money as a developer. It's about how to build community. The new urbanists are more important now then we have been before, because we can help communities understand how to accept, welcome, and shape the growth that wants to come into the core.

The New Urbanism envisions regions where transit plays a much larger role. What are your views on transit today and how is it shaping regions?

Dixon: Transit has never been more important to a region's success than it is now. Transit concentrates development, and walkability is such a priority for people in decisions about where they're going to live, shop, play, and work. From office to housing to retail, the market is rewarding walkability. And if you look at which regions are growing their economies fastest, you'll find strong walkable downtowns and multiple walkable cores, like in Washington DC or Boston. So, Transit is absolutely essential to the ability to grow and develop this way.

Henderson: [In] some parts of the country, we are seeing major transit extensions. Of course, the issue right now is whether or not that will continue to be funded at the federal level. In regions with tight housing markets, like the Silicon Valley, transit begins to build equity regionally, because you can live in areas without huge transportation cost burdens and with access the job base. Of course, especially in Silicon Valley, there's still a huge last-mile problem. Putting stations in areas that are transit-ready is crucial to the health of a successful region.

So, are we at the cusp of a transportation revolution? How is that, and should it be shaping regional planning?

Dixon: The impact is happening much faster than I thought it would and will be much more disruptive and fundamental. Over the next five years, three years actually, the first generation of shared autonomous vehicles (AVs) will be in mass production. The technology and the understanding of how to use it to create first- and last-mile connection is here. They need their own guided right-of-way, because they can't move in mixed traffic and there are limitations, but they're going to extend the walkable zone around a transit-oriented development, from a quarter mile to a mile or two. This will lower costs for Uber and Lyft, because the driver represents about 50 percent of the cost of these vehicles. So, the initial round of AVs will be very pro-transit. This will be particularly helpful for larger-scale, denser, walkable suburban centers—the polycentric regional model. In places like the DC region, they will be particularly good at expanding the potential for transit-oriented, new suburban centers. In very urban locations it will be a bit harder because you have to create the right of way. By the early 2020s, Ford and GM are going to be mass-producing shared vehicles that go into mixed traffic on city streets. Whole urban neighborhoods will become transit-oriented to an extent that they aren't today.

Many knowledgeable people were saying that within 10 to 15 years, parking requirements will drop by anywhere from 50 to 80 percent. Shared autonomous vehicles don't park. So we're going to have a ton of extra parking spaces in cities and suburban walkable centers, which set the stage for a whole new round of intensification and densification, and new urbanists will provide an understanding of this growth. This will put more people on the street, which will create demand for retail and street activation what we all yearn for. As e-commerce out-competes big boxes and other retail, it will be important to have more demand to keep urban centers relevant and competitive… So it's going to take more density in 5 or 10 years than it does today to support life on the street.

Henderson: One problem for AVs is that people don’t like to share. UberPool is an example. If people have an economic choice, they won't share rides. Peter Calthorpe says that if AVs are not electric, the carbon emissions will blow up instead of being mitigated, and I think that's something we should think seriously about. What are the criteria for AVs? Should they be electric? What if the grid itself is powered by coal? So there are layers of implications from a climate change perspective that we need to think about.

Let me bring this back this back to a bone of contention and perplexing problem from the beginning of New Urbanism and that is the balance between infill and greenfill development. Markets have changed and people's desires have changed. Do you have any thoughts on how a regional planner should approach that infill/greenfill balance today?

Henderson: If you look at Joe Minicozzi's work about the highest return on investment from a tax base perspective, there are solid fiscal reasons why greenfield development would give pause to most cities. I’ve seen urban counties recently make awful decisions about massive greenfield development. So, from a sustainability, climate change, and economics perspective, one would say that cities should prioritize infill. But if they don't, I think you can still get in the market with walkable, new communities. In southern New Mexico at the regional scale, the preferred scenario for the community as a whole was extensions of existing communities. And those are in essence greenfield.

Dixon: There's a lot of data out there that shows that greenfield sprawl is a really lousy investment, and it is setting up suburban communities for failure. And Calthorpe's work for Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission has been hugely influential in getting local, regional, and state decision-makers to see the writing on the wall. I want to mention the rise in suburban poverty. Since 2000, most of the growth in close-in suburbs and maybe a quarter to half of the growth in outer suburbs are people at or below the poverty line. [That’s partly because since] 2000, urban housing costs have risen so much faster than suburban housing costs. Suburban communities can't afford to make bad investments or bad decisions around their future fiscal health. They can't afford to encourage suburban office or single-family sprawl housing that's going to lose value over time. They have to pay more attention today to building their local tax base than they have at anytime since these suburbs started to grow after World War II.

Can each of you name an innovative, interesting regional planning project and just a couple reasons why it is cool and what it is doing for that region.

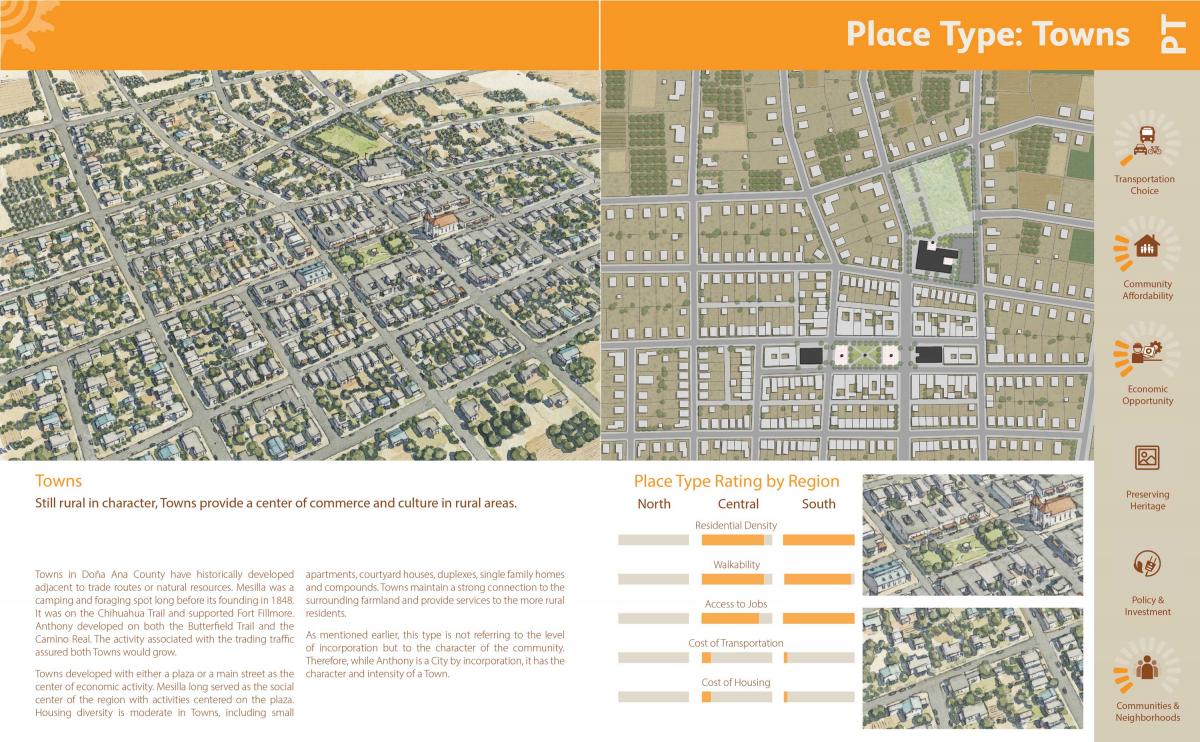

Henderson: At the risk of talking about our own work, the Dona Ana County regional plan was also pretty powerful, largely because of the success at engaging the underrepresented Hispanic community. They were empowered to the point that some, afterward, were appointed to the planning commission. The biggest issue for those folks was understanding place. And so the critical use of place types was really important for people to be able to make a preference on growth. Even though we had support from developers and politicians, the biggest thing that gives me hope for long-term success and implementation is that all of the folks with no English who came to the final adoption meeting and spoke in favor of the vision.

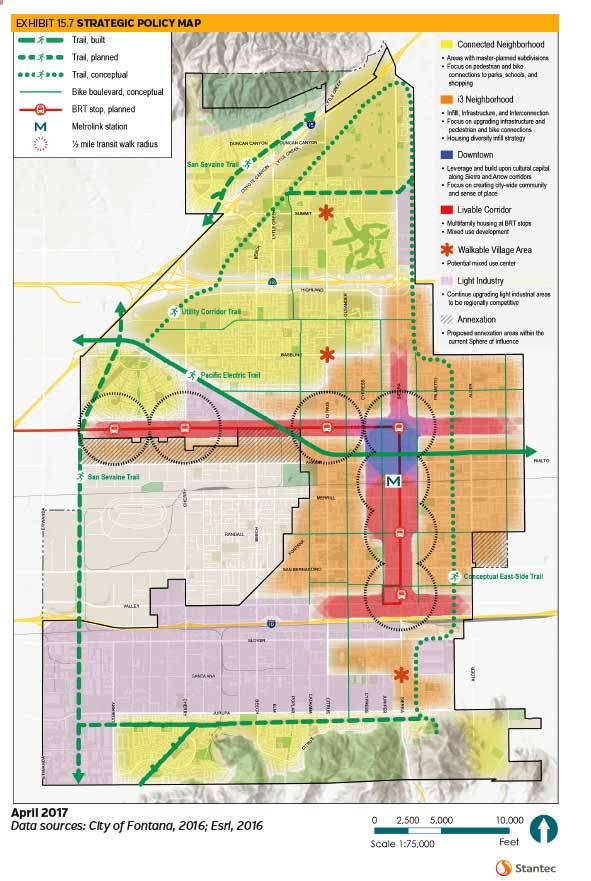

Dixon: One of the greater challenges for smart growth is bringing low-income communities into that discussion, and it's really gratifying to hear about how you've done that. I was going to mention Calthorpe and his ability to provide metrics. My first job was for somebody who said a word is worth a thousand pictures and I've begun to think maybe he was right. Compact, walkable, transit-oriented, new urbanist development makes more sense for public health, fiscal health, and mobility, and metrics clarify those benefits. And I've done a lot of work in mid-Ohio, framing for new suburban downtowns—plans for Dublin, Ohio, and Delhi, Ohio, and we're doing some work in Dayton now. Some of that work preceded and helped to bring in Peter Calthorpe, and then his ability to articulate the case, provide metrics, and crystalize the argument has been hugely important. I want to mention two projects that we've been involved in at Stantec in Corpus Christi, Texas, and Fontana, California, that launched regional conversations that led to a fundamental shift from a sprawl mentality to a smart growth mentality. And it happened not by convening the region, but by going out to suburban neighborhoods, to urban neighborhoods, and bringing together elective leadership and communities. Those conversations really did produce political support or solutions that definitely wasn't there when the project started.

Not only are metrics important, but the pictures of what this future looks and feels like are absolutely central to these discussions. New urbanists provide the visuals, the metrics, and the spoken vocabulary that unlock these conversations. A lot of people are searching for the leadership that New Urbanism can offer.