US DOT advances highway transformations

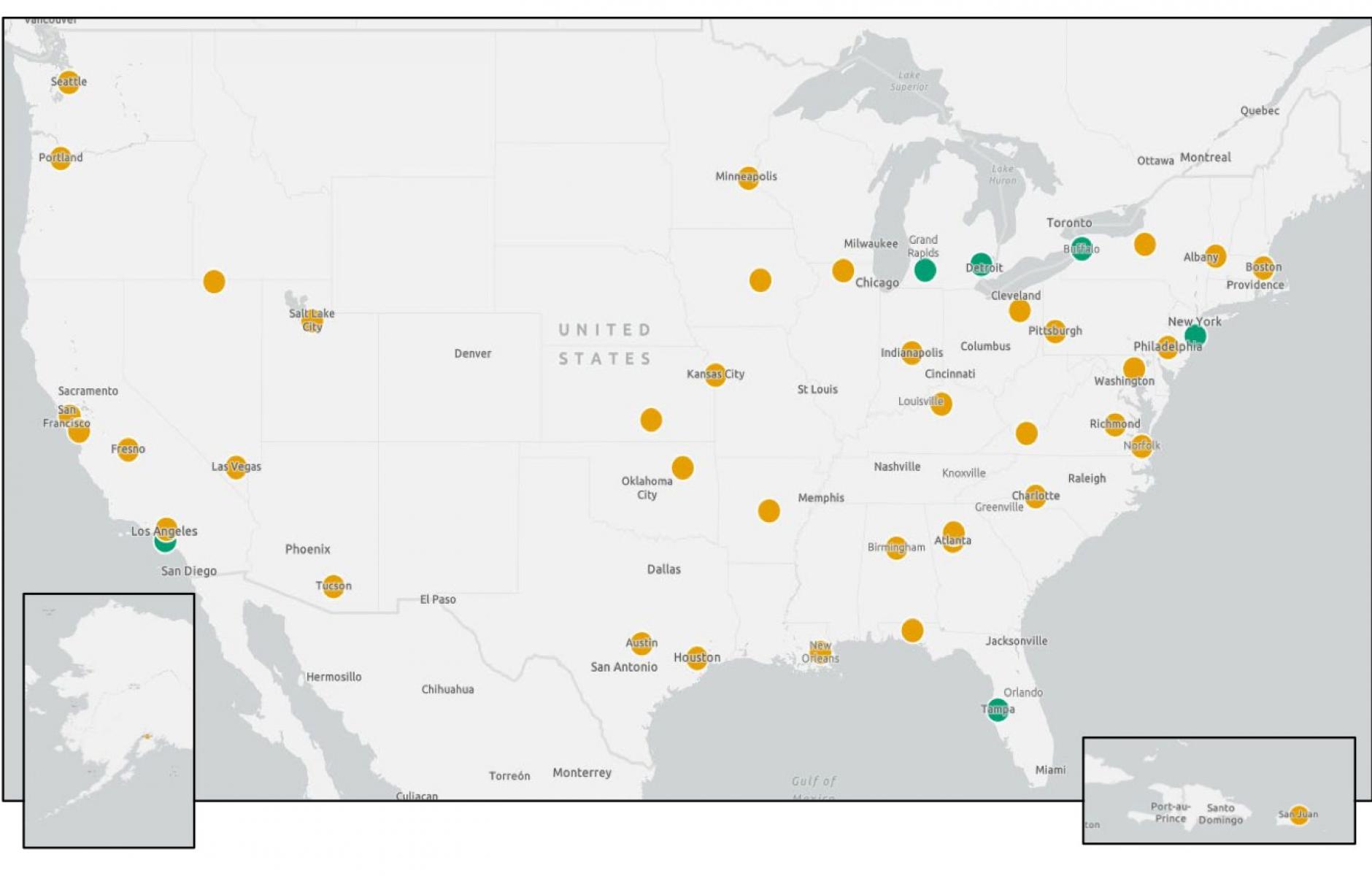

A growing number of cities are looking to transform highways that divide neighborhoods. To address that issue, the US DOT announced this week the first round of Reconnecting Communities grants, including six capital and 39 planning projects. The grants total $185 million, out of $1 billion allocated for the program.

Given the huge amounts of money spent on highways, one could argue this is a drop in the bucket—but the grants will make a difference. All of the capital projects are likely to be implemented. The planning grants will increase the likelihood that many more projects will be completed in the future.

Just as important, the grants signal which kinds of highway transformations US DOT is likely to prioritize going forward. The Reconnecting Communities program—largely aimed at transforming in-city highways—is the first federal earmark of its kind. And, it is hoped, the program is a step toward a larger effort to undo the considerable damage from 20th Century transportation planning.

Of the 10 nominees for CNU's upcoming 2023 Freeways Without Futures report, at least five of them received Reconnecting Communities grants. The overlap shows the alignment with CNU's Freeways Without Futures program, which also focuses on repairing damage from in-city road construction.

Because the damage came in many forms—including freeways through cities, access ramps and overpasses that devalue city blocks, surface street widenings, and one-way networks—the range of projects is wide. Capital grants include caps over freeways, transformation of a freeway, restoration of one-way downtown streets to two-way travel, removal of highway ramps, and a pedestrian tunnel. The biggest category of planning grants is in highway transformation and corridor studies, followed by caps over freeways. Also, multiuse trails, demolition of highway ramps, bike-ped bridges, and land-use changes after infrastructure removal are being studied.

In terms of the capital grants, the biggest single allocation is toward a substantial freeway cap over the Kensington Expressway in Buffalo, New York. The $55 million grant will add to $1 billion already given by the State of New York, fully funding this project. The expressway, which is a major route from the suburbs into downtown, replaced a beautiful Olmsted-designed parkway, dividing neighborhoods in East Buffalo, currently a low-income area.

DOT describes the project: “Above ground, Humboldt Parkway would be redesigned not just for cars but for pedestrians and bicyclists with traffic-calming measures, crosswalks, bicycle lanes, and pedestrian and bicycle signals. It would also include a tree-lined walkable linear park in the median with Victorian gardens, sidewalks, and benches, connecting it with the adjacent Martin Luther King Jr. Park.”

Below this new public space, a 0.8-tenths-of-a-mile, six-lane tunnel will carry traffic underground. The highway, in other words, will remain. Like many of these projects, the Kensington Expressway has been cited by CNU’s Freeways Without Futures, where the hope was for a restoration of the historic boulevard rather than a cap. While highway caps account for a significant number of grants, many projects are funded that would transform highways in more fundamental ways.

One of the more interesting examples is in Kalamazoo, Michigan—not involving a freeway, but downtown streets that were converted to three-lane, one-way couplets to move traffic quickly through the urban core at the expense of walkability and access of nearby neighborhoods.

The project will restore two-way travel on these streets. As the city describes it:

“The project will upgrade Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues with traffic calming measures and pedestrian, bicycle, and transit improvements. Michigan DOT designated these roads as one-way roads approximately 60 years ago, creating a high-speed and high-volume traffic corridor through downtown, dividing the community and creating access barriers for neighborhoods.”

The $12.27 million grant will cover half of the capital project, which will also upgrade very old water and sewer infrastructure under the thoroughfares.

In Long Beach, California, $30 million was allocated to remove a freeway barrier to the ocean. According to DOT:

“The project’s realignment and transformation of Shoreline Drive will convert the urban freeway corridor into a landscaped local roadway, creating approximately 5.5 acres for park space and serving as a gateway to better connect residents, visitors, and workers to the Pacific Ocean, local destinations, and downtown Long Beach.”

The Shoreline Drive project has been profiled in CNU’s Highways-to-Boulevards initiative.

In addition to the capital projects, the more numerous planning grants will advance nearly two score interesting projects—many of which CNU has promoted. In some cases, more planning is needed even as a project is assured of being built. The removal of the I-81 viaduct through downtown Syracuse, which has appeared on all seven Freeways Without Futures report since 2008, needs more design to make the final project better—even though it is now assured of construction. According to DOT:

“Funds will be used to study how best to address inequities on the south side of Syracuse created by a raised highway and elevated railroad that inhibit access to jobs, education, healthcare, and recreation. The project will study the most effective methods to reconnect the project area, with considerations for pedestrian, bicycle, and public transportation/Bus Rapid Transit pathways along multiple potential east-west routes across the dividing facilities while supporting community engagement.”

Many of the planning grants caught my eye, including a design study for the transformation of Monterey Road Highway to a “grand boulevard.” Currently, “Monterey Road is one of the highest-fatality corridors in San Jose. With high vehicle speeds, missing sidewalks, and a lack of safe crossings, the road is both hazardous and divides adjacent communities. We welcome investments that will help transform this corridor so pedestrians and drivers alike stay safe and areas downtown are connected,” said Reps. Lofgren, Eshoo, and Panetta, Congressional representatives of the corridor.

The strong political support indicates this project is likely to move forward in the future. In general, these Reconnecting Communities grants focus on projects with the political support needed for implementation.

Other notable projects that received planning funding include The Claiborne Expressway in New Orleans, the I-980 corridor in Oakland, and Baltimore’s “Highway to Nowhere,” the US 40/Franklin-Mulberry Expressway. The planning is required before anything else can be done.

Here’s a full list of projects that have been implemented.