The state of the art of suburban retrofit

Case Studies in Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Strategies for Urgent Challenges, the latest book in a series by June Williamson and Ellen Dunham-Jones, is about creating real value from underutilized places. The volume focuses on automobile-oriented, conventional suburbs, which comprise about 90 percent of US metropolitan areas.

More than a half century of literature describes the flaws of conventional suburbs. Yet imagining them as something different is hard. The roads, parking lots, buildings, landscaping, and infrastructure are built, representing trillions of dollars in sunk costs. Williamson and Dunham-Jones have helped to change our thinking about what is possible in the American built environment.

Beginning with their 2009 book, Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs, the authors have highlighted the opportunities of suburbs to transform into better places. This new book reports on projects built over the last decade that have capitalized on that potential.

What is a suburb? Williamson and Dunham-Jones avoid complicated formulas by focusing on built form. The name suburb—combining the roots for “beneath” or “less important” and “city”—essentially means less than urban. It’s not about distance from the downtown core of a major city. Many cities have suburban areas within them—and many suburbs have sections that are essentially urban. Here's part of the authors’ explanation:

A property with a building surrounded by surfaces that are lawn or paved for parking we define as suburban form. If the building fronts a sidewalk and places the parking either under or behind it, that’s urban form. If the road infrastructure is dendritic—branching out like a tree—that’s suburban form. If the streets are networked—interconnected and walkable, with frequent intersections—that’s urban form.

With that form-based definition in mind, the authors explore how suburbs can be retrofitted. One of the goals of suburban retrofit is to bring some much-needed walkable urbanism to the suburbs. Case Studies in Retrofitting Suburbia offers examples of how to upgrade suburban areas to real urbanism. And yet the book is not dogmatic on this point, because that upgrade may not be the best solution in any given location. Suburbs can also be retrofitted through reinhabitation of vacant buildings—or regreening to restore ecological systems that improve stormwater management. The authors are guided less by theory than on-the-ground research:

Our database of retrofitting examples has exploded over the past decade from 80 to over 2,000 entries. Slightly more than half we classify as redevelopments, only 2 percent as regreenings, and the rest comprise incomplete tallies of the vast number of reinhabitations and adopted corridor retrofit plans.

Why should suburbs be retrofitted at all? Many suburbs are so badly put together that some urbanists argue that resources would be better spent focusing on older cities and towns. Historic communities tend to have good “bones”—well-connected streets and infrastructure with interesting buildings made by hand. But with 90 percent of our metro areas built as conventional suburbs, and most people living in such places, the problems can’t be ignored.

Reading this book strengthens my view that suburbs should be transformed for yet another reason. The very flaws of the suburbs create the potential for improvement. For those who do the hard work of transforming suburbs, the gain is all that much greater. And as the authors make clear, the work can be completed incrementally, one step at a time. Still, retrofitting suburbia is hard, and definitely not for everyone.

Case Studies in Retrofitting Suburbia is divided into two sections. The first section lays out “urban suburban challenges” posed by automobile-oriented communities. The authors explain how these problems can being addressed through retrofit. The challenges are:

- Disrupt automobile dependence

- Improve public health

- Support an aging population

- Leverage social capital for equity

- Compete for jobs

- Add water and energy resilience

Section one is an overture for the case studies, which form the heart of the book, as the title suggests. The case studies are aided by the authors’ own drawings, original photographs, and illustrations from other sources.

Transforming an industrial campus

Discussion of suburban transformation usually revolves shopping malls. But suburbs include many kinds of underutilized sites, such as a 300-acre former IBM research and manufacturing campus in Austin, Texas. This site is not a typical “brownfield” site. Selectric typewriters, powered by early computer technology, were developed and built on this site from the 1960s through the 1980s.

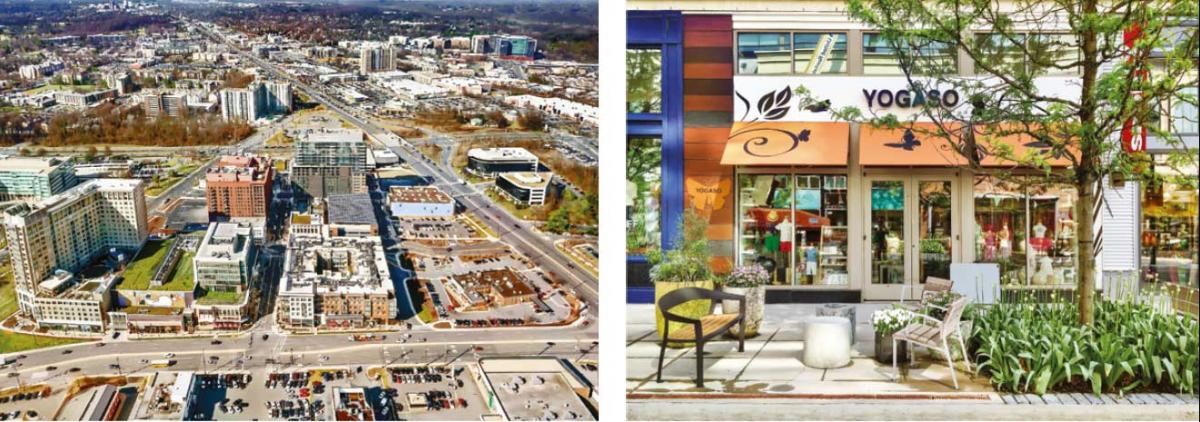

This site is being redeveloped as Austin’s second downtown, nine miles from the city’s historic core, called The Domain. The developer-led project “has inserted chunks of walkable urbanism into a sprawling office park,” the authors report. “The bits are anchored by familiar department stores but centered on well-designed pedestrian-oriented streets lined by loads of brand-name shops topped by loads more apartments. Bars and restaurants spill out into many of the popular public spaces.

“While detractors deride The Domain as ‘living in a mall,’ the strategy has been very successful at attracting the next generation of knowledge workers to approximately 10 million new square feet, twelve miles north of downtown Austin, Texas.” The development has successfully boosted jobs, tax revenues, and property values, the authors report.

From office park to downtown

Ten miles west of Miami, Florida, an 80 percent Hispanic community is building a downtown on the site of a 120-acre, 1970s office park. Rather than focusing on housing for mostly single millennials, Downtown Doral is offering civic assets and attracting families. The development includes a city hall, two charter schools, a library, a public art pavilion, and a three-acre city park.

Downtown Doral, which took shape after the 2008 recession, is using the principles of “Lean Urbanism.” A more connected street system is being built with sidewalks and a mix of uses, yet Downtown Doral also retains existing roads and some of the original office buildings that have provided a steady revenue stream for the developer. Practicality guides the approach to mixed-use.

“In Doral, continuous fine-grained retail and restaurant frontage on Main Street encourages walking, although housed in cheaper to-build one-story liner buildings,” the authors report. “Not tucking them into the ground floors of high-rise residential buildings limits risk to investors should either use fail. Similarly, the high-rises are independent structures from their parking decks.”

Downtown Doral is becoming an urban core for a suburban city while avoiding a blank slate approach. The resulting development is more sustainable, and also contributes to a unique place.

Corridor retrofit

The transformation of a central corridor in Lancaster, California, which had just gotten underway as Williamson and Dunham-Jones finished their first book, is among the most inspiring stories. The city shrank a five-lane arterial down to two lanes, removed seven traffic lights, cut the speed limit down to 15 mph, and rebranded the area as The BLVD. The BLVD quickly became the social heart of the city, generating $273 million in economic activity with 37 new businesses and more than 800 housing units, the author’s report.

“Despite all of the new activity on The BLVD—or because of it—public safety has dramatically improved. Total motor vehicle collisions are down 38 percent and pedestrian-involved collisions have plummeted by 78 percent.”

The success of this project has set a new planning and development course for Lancaster, a suburban city in eastern Los Angeles County that grew up since the middle of the 20th Century.

“Based on the behavioral changes he saw after the road diet, (City Planning Director Brian) Ludicke introduced a Complete Streets Master Plan for the entire city in 2016. The Antelope Valley Healthcare District also took notice and in collaboration with the city are planning to redevelop automobile-oriented properties surrounding the to-be-rebuilt hospital into a walkable, mixed-use, medical, commercial, residential district called Medical Main Street.”

Reimagining a health district

The 1,000-acre Baton Rouge Health District epitomizes suburban medical facilities with more than 17,000 parking spaces and 12 million square feet of disconnected development. A 2015 report examines the district like a patient, pointing out symptoms like traffic congestion, automobile dependence, and few opportunities for active transportation contributing to environmental health factors like lack of exercise and obesity. Sponsored by the Baton Rouge Area Foundation, the report envisions this site converted into a walkable urban district with a mix of uses and civic sites. “Treatments include infilling the street network and adding a 7.4-mile walking and biking trail to improve efficiency and choice in the transportation network. The follow-up tests include metrics on travel speed, bicycle and pedestrian counts, and surveys of employee travel behavior.”

This visioning exercise was surprisingly influential. “Implementation began right away, with formation of the Baton Rouge Health District as a coordinated nonprofit entity, appointment of an executive director, fast-tracking by local authorities of a complete streets project for the district’s most congested and pedestrian-unfriendly arterial corridors, and construction of new segments on the ‘Health Loop Trail.’ Four miles of additional sidewalks and trails will be added in the next years.”

Whether the full vision will be implemented remains to be seen. However, the initiative is part of a nationwide trend of hospitals recognizing that place-based solutions are critical to community health. “As of late 2019, 46 health systems (many of which are the largest private sector employers in their states and represent about 20 percent of the nation’s hospitals) have joined the Healthcare Anchor Network’s commitment to leverage hiring, purchasing, and place-based investments to build more inclusive and sustainable local economies.”

Health districts, corridors, office parks, industrial campuses—these are just some of the suburban places that are ripe for retrofit. Such transformations will help to define land-use planning and development in the 2020s. Case Studies in Retrofitting Suburbia is now the essential reference on the topic.